RIP, MIX, LEARN: FROM CASE LAW TO CASEBOOKS

Like many projects, the Free Law Reporter (FLR) started out as way to scratch an itch for ourselves. As a publisher of legal education materials and developer of legal education resources, CALI finds itself doing things with the text of the law all the time. Our open casebook project, eLangdell, is the most obvious example.

The theme of the 2006 Conference for Law School Computing was “Rip, Mix, Learn” and first introduced the idea of open access casebooks and what later became the eLangdell project. At the keynote talk I laid out a path to open access electronic casebooks using public domain case law as a starting point. On the ebook front, I was a couple of years early.

The theme of the 2006 Conference for Law School Computing was “Rip, Mix, Learn” and first introduced the idea of open access casebooks and what later became the eLangdell project. At the keynote talk I laid out a path to open access electronic casebooks using public domain case law as a starting point. On the ebook front, I was a couple of years early.

The basic idea was that casebooks were made up of cases (mostly) and that it was a fairly obvious idea to give the full text of cases to law faculty so that they could write their own casebooks and deliver them to their students electronically via the Web or as PDF files. This was before the Amazon Kindle and Apple iPad legitimized the ebook marketplace.

The devilish details involved getting our hands on the full text of cases. We did a quick-and-dirty study of the 100 top casebooks and found that there was a lot of overlap in the cases. This was not too surprising, but it meant that the universe of case law — as represented by all the cases in all the law school casebooks — was only about 5,000 cases, and that if you extended that to all the cases mentioned — not just included — in a casebook, the number was closer to 15,000. I approached the major vendors of online case databases to try to obtain unencumbered copies of these cases, but I had no luck. Although disappointing, this too is not surprising, considering that these same case law database vendors are part of larger corporations that also sell print casebooks to the law school market.

Of course, the cases themselves are public domain and anyone with a userID and password could access and download the cases I needed. But the end-user agreements that every user must click “I Agree” to, include contract language that precluded anyone from making copies of these public domain cases for anything but personal use. Contract law trumped access to the public domain materials.

Fast forward a couple of years, to the appearance of Carl Malamud’s public.resource.or  g, providing tarballs of well-formatted case law every single week. Add to that the promise of re-keying a large back catalog of cases via the YesWeScan.org project (also from public.resource.org) and we could now begin to explore ideas that had been simmering on the back burner for several years.

g, providing tarballs of well-formatted case law every single week. Add to that the promise of re-keying a large back catalog of cases via the YesWeScan.org project (also from public.resource.org) and we could now begin to explore ideas that had been simmering on the back burner for several years.

CASE SEARCH AS EBOOK: LEAN FORWARD / LEAN BACK

One of the neat features at FreeLawReporter.org is that it allows you to convert the results of a search into a downloadable ebook in .epub format which you can read on your Apple iPad or Barnes & Noble Nook and other ereader devices. (.epub ebooks may be readable on Amazon Kindles soon.) The idea for this feature sprang from some articles I had read about how people read on the Web versus how people read books. Jakob Nielsen explains it well in a post entitled “Writing Style for Print vs. Web”:

Print publications — from newspaper articles to marketing brochures — contain linear content that’s often consumed in a more relaxed setting and manner than the solution-hunting behavior that characterizes most high-value Web use.

What does this have to do with case law and ebooks?

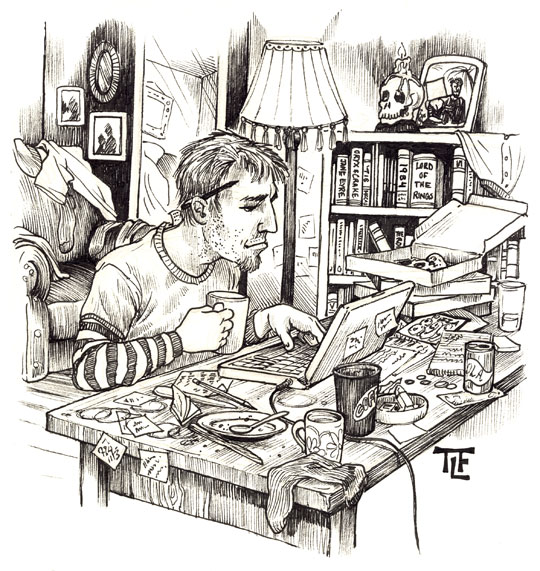

It’s all about what kind of reading you are doing. When you are doing research — especially online research, which involves refining your search terms, clicking through lots of links, and opening lots of browser tabs — you a re “leaning forward,” actively looking for something that you plan to read in greater depth later. In the case of legal research, the results of your efforts are a collection of cases — dozens or hundreds of pages long. Once you have found the most on-point cases, you know that you need to read them deeply and carefully in order to follow and understand the arguments. This type of reading I call “leaning back,” and is more suited to the environment you create as a book reader than the one you create as a Web reader.

re “leaning forward,” actively looking for something that you plan to read in greater depth later. In the case of legal research, the results of your efforts are a collection of cases — dozens or hundreds of pages long. Once you have found the most on-point cases, you know that you need to read them deeply and carefully in order to follow and understand the arguments. This type of reading I call “leaning back,” and is more suited to the environment you create as a book reader than the one you create as a Web reader.

Turning case law searches into books seems like a natural consequence of the movement between “lean forward” Web searching and “lean back” book reading. There is a lot of anecdotal writing about this, but I am h ard-pressed to find scientific literature that is definitive. Fortunately, with FreeLawReporter.org, open source tools, and a smart developer, we can experiment and let users decide what works best for them. This is an important point that deserves some expansion.

“FREE” AS IN “FREE TO EXPERIMENT AND INNOVATE”

The primary product of the online legal database vendors is targeted primarily at big law firms. They get the big cases, have the big clients, and spend the most on legal research. As you move down the scale of firm size, you also move down in ability and willingness to pay for legal research, or ability to charge the cost of legal research back to the client. By the time you arrive at small firms and solo practitioners, the amount of time spent doing legal research is much reduced, and, in the case of purely transactional practices, legal research is done only rarely.

The use of these databases in legal education, however, is different. Legal research instructors try to give students a flavor for what using the databases in the real world will be like, but without knowing what type of law the students will end up practicing. The instruction, therefore, must be generalized. The databases are optimized for users who have almost unlimited (in time and cost) access. The databases were not designed for optimizing legal education. With the online database vendors, you get a powerful and comprehensive product, but you cannot change it to suit particular educational goals. You must adjust to it.

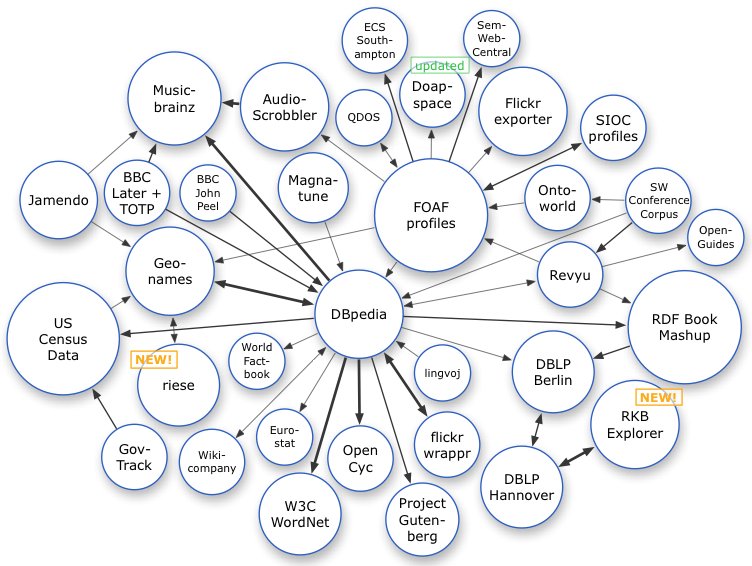

A database of the law should be available to the legal education community as a free, open, and customizable system that has affordances for instructors and researchers, i.e., law librarians and law faculty. We are only beginning to explore these ideas, but one analogy is that Wexis is to the Free Law Reporter as Windows is to Linux. The free and open aspect of the Free Law Reporter (FLR) will let legal research instructors, law faculty, law students, and even the public do things that are not possible within the contractually locked-down and/or digitally rights-managed systems that are designed primarily as a product for the most expensive lawyers in the marketplace.

With FLR, we can experiment with tweaking the algorithms behind the search engine to optimize for specific legal research situations. With FLR, we could create closed-universe subsets that could be used for legal research exercises or even final exams. With FLR, we could try out all sorts of things that we cannot do anywhere else.

I don’t expect FLR to be a replacement for anything else. It is a new thing that we have not seen before — a playground, a workshop, a research project, and a tool shed for legal educators. It can only grow in value and increase in quality, but we need help.

WHY “REPORTER”?

The choice of the name “Free Law Reporter” was deliberate. The “free” refers to both the cost and the open source aspects of the project, in the Free Software Foundation tradition. Richard Stallman has often expounded on the importance of access to the code you run on your computer; so too should every citizen have access to the laws of the land. In the past, case law was outsourced by the government to vendors who created the original Reporter system, which was made widely available to the public via state, county, and academic law libraries. Many libraries have, of necessity, cut back on their print subscriptions, reduced their hours of access, reduced their staff, or closed altogether, but the real loss of access to the public started when the law transitioned to online legal databases.

Now that online access to the law is the new normal, the disintermediation of law libraries is nearly complete, but the courts and governments have not kept up with the equal access during the transition. In the legal publishing lifecycle, there is an opportunity to add value, between the generation of the raw data of law, and the fee-based publication of law by online database vendors. FLR, with the help of law librarians, can seize that opportunity. This is not just a value proposition respecting public access to the law. Academic law libraries should have free and open access to the law, access that allows them to define and construct the educational environment for law students.

I am not sure whether the Free Law Reporter (FLR) can grow into what I envision. We are only at the beginning, but I believe it’s about time we got started. I do know that we cannot succeed without the assistance and participation of the law librarian community. Right now, this assistance is mostly provided by law schools’ continued annual CALI membership.

we cannot succeed without the assistance and participation of the law librarian community. Right now, this assistance is mostly provided by law schools’ continued annual CALI membership.

We are working to make participation in the growth of FLR possible, by finding ways to tap the cognitive surplus of law librarians, students, faculty, and lawyers. The key challenge, I believe, is the construction of a participation framework where many small contributions can be aggregated into something of great, cumulative value. Wikipedia, Linux, and many other open source projects are exemplars from which we can take cues. There is so much to do and I am excited by the technical and organizational challenges that FLR presents. Expect to hear more from us about this project as we get our legs underneath us.

John Mayer is the Executive Director of the Center for Computer-Assisted Legal Instruction (CALI), a 501(c)(3) consortium of over 200 US law schools. He has a BS in Computer Science from Northwestern University and an MSCS from the Illinois Institute of Technology. He can reached at jmayer@cali.org or @johnpmayer.

John Mayer is the Executive Director of the Center for Computer-Assisted Legal Instruction (CALI), a 501(c)(3) consortium of over 200 US law schools. He has a BS in Computer Science from Northwestern University and an MSCS from the Illinois Institute of Technology. He can reached at jmayer@cali.org or @johnpmayer.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor-in-Chief is Robert Richards, to whom queries should be directed.

The biggest advantage of established legal publishing houses, as opposed to new start-ups, is their brand recognition, and the chance to position themselves as gatekeepers for high quality information. The corresponding threat is –- again –- based on new technologies: Services such as

The biggest advantage of established legal publishing houses, as opposed to new start-ups, is their brand recognition, and the chance to position themselves as gatekeepers for high quality information. The corresponding threat is –- again –- based on new technologies: Services such as