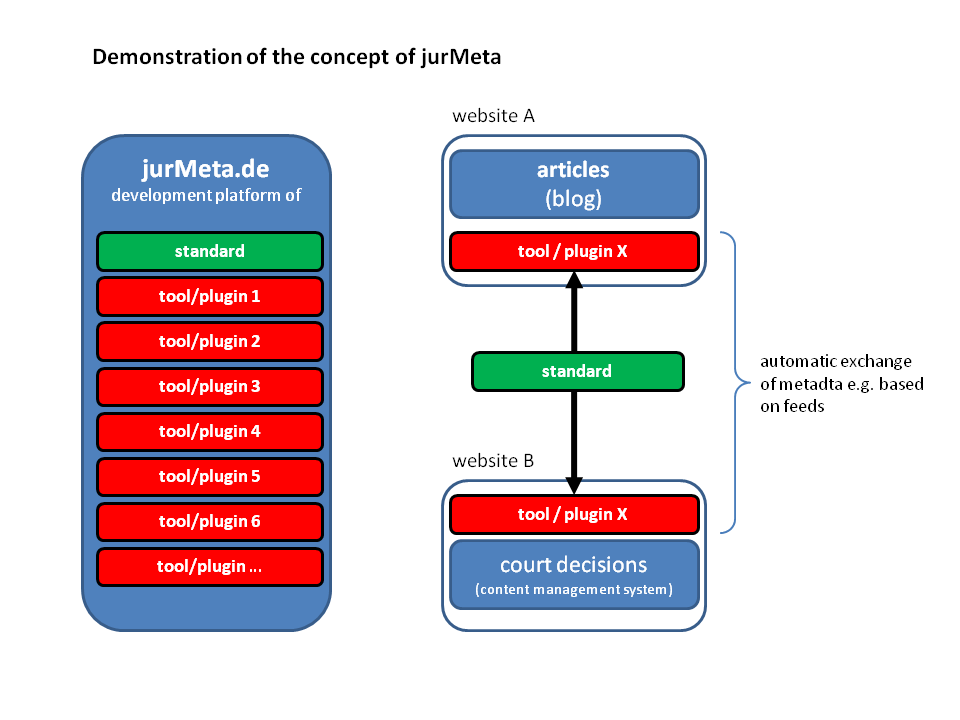

This article is about jurMeta, a new metadata initiative for legal texts that I initiated with two colleagues in Germany. Our vision for jurMeta goes beyond a standard set of metadata tags and predefined legal terms. JurMeta is a whole concept allowing the automatic annotation, exchange and linking of legal documents on the Internet for a wide community. Technically, this will be achieved by easy-to-use plugins for blog systems and content management systems. Using this system, citations to a court decision in a blog post could be linked with the court decision itself on another website by simply installing a plugin. On http://jurmeta.de, I have already started a platform for the standard itself and for tools that can be built on top of it in future.

This article is about jurMeta, a new metadata initiative for legal texts that I initiated with two colleagues in Germany. Our vision for jurMeta goes beyond a standard set of metadata tags and predefined legal terms. JurMeta is a whole concept allowing the automatic annotation, exchange and linking of legal documents on the Internet for a wide community. Technically, this will be achieved by easy-to-use plugins for blog systems and content management systems. Using this system, citations to a court decision in a blog post could be linked with the court decision itself on another website by simply installing a plugin. On http://jurmeta.de, I have already started a platform for the standard itself and for tools that can be built on top of it in future.

We need a practical standard

After having Googled metadata standards for legal texts for hours, having screened dozens of projects, and having seen a lot of ontologies and legal topic maps, I suggested to my colleague Andreas Bock: “Let’s go and create our own metadata standard. Everything I’ve seen so far is too complex and does not fit our practical needs.”

In August 2009, we had just released kjur.de – “Recht einfach finden” — “Law easily found” — a small, Google-like search engine for legal documents in the German language. The concept is to offer better-structured access to freely available legal content by avoiding all that noise that bothers you when using one of the big search engines.

Some other vertical search engines for legal content (such as these and Google Scholar) have been developed in recent years. But most are built on a Google custom search, and so they offer only limited possibilities for analyzing content. We chose a flexible but more difficult method, and designed our back-end on top of an existing crawler. Legal acts, blogs, Wikipedia articles, and a bibliography were the first content types in kjur.de. Unfortunately, a few weeks after the release, the nice beep of a hard disc head crash and a badly configured RAID sent a key part of our document processing into digital nirvana.

However, this created a golden opportunity to address the increased demands on our system. We decided to shift from a less- to a more-structured data processing and storage approach. Our new, flexible, and scalable process mined the documents for particular legal information, and automatically annotated the documents with metadata, marked up in XML. In homage to Yahoo pipes, we called our process “kjur pipe.” The first goal was to offer more detailed access to legal information and, with query expansion, to provide an extended search. In order to be able do this, we needed a document and metadata standard.

jurMeta at the EDV-Gerichtstag 2009

Part two of the history of jurMeta concerns a session at the EDV-Gerichtstag in Saarbrucken, a conference — held annually in Germany — on technical aspects of legal documents. Ralf Zosel, who organized the session about free legal online projects, invited us to talk about our experiences with our project. Ralf created http://jurawiki.de, the first and best-known legal online community in Germany.

We spoke about the accessibility of law statutes and court decisions on governmental websites. The German landscape of official websites with legal content is split up into a large number of very heterogeneous portals. For example, at http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de, one can find most of the consolidated federal acts. Court decisions are available from five different sites: the Federal Constitutional Court, the Federal Civil Court, the Federal Employment Court, the Federal Patent Court, and the Federal Finance Court. Additionally, most of the 16 federal states have their own databases with court decisions and the most important statutes.

We spoke about the accessibility of law statutes and court decisions on governmental websites. The German landscape of official websites with legal content is split up into a large number of very heterogeneous portals. For example, at http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de, one can find most of the consolidated federal acts. Court decisions are available from five different sites: the Federal Constitutional Court, the Federal Civil Court, the Federal Employment Court, the Federal Patent Court, and the Federal Finance Court. Additionally, most of the 16 federal states have their own databases with court decisions and the most important statutes.

An interesting detail is that many of these free databases provided by the government authorities are hosted by a publisher who sells the same documents on his own web portal. That these sites are protected by robots.txt files and meta tags clearly demonstrates that search spiders are not welcome. Some of the official sites allow crawling, but use complicated JavaScripts that can cause infinite crawling loops. Therefore, except for the database of the Federal Constitutional Court, the German Yahoo and Google indices contain not a single court decision indexed from the federal courts in Germany.

Moreover, the automatic extraction of metadata from online German legal documents poses a big problem. Let me demonstrate this with a metadata field that basically exists in every .doc, .pdf, or .html file — the title. The users of our search engine like to see the search results with titles that tell something about what they can find behind the link; for example, the name of the court, the file number, and the date. It is a pity that the document titles of the crawled documents rarely contain any useful information. Most of the titles of court decisions on public websites contain the file name of the MS-Word template, the name of the secretary of the court who wrote the decision, or simply “New Document.doc.” So we had to program a script for metadata extraction in order to build nice titles on our own.

Therefore, in the session at the EDV-Gerichtstag 2009, my colleague suggested to the government that they publish official legal texts on a centralized website — and that those texts should be structured and should contain descriptive metadata, if those metadata appear in the original documents. If the government took these steps, my colleague contended, the publishers of legal information would be free to compete with respect to creating the best information system and the best added value for the user, and would not spend too much time or money adding technical structure to primary legal texts.

How to give birth to a vital metadata baby

How to give birth to a vital metadata baby

My role in the session was to offer some ideas about what a metadata standard could look like. When I prepared my slides, I was very skeptical. I was afraid of presenting a stillborn child, because nobody needs a new metadata standard. Who should use it — and why? I had had my very own experiences with XML metadata-annotated documents when, in 2001, I created a system called VERIS, a database containing public procurement case law. It was the first database — and I think the only one — that allowed the user to export court decisions in the format of the XML Standard of Court Decisions of Saarbrücken. Nobody was interested in this functionality except for the person who copied the whole database piece by piece and created his own in order to sell it. Although a court ordered him to stop, he demonstrated the interoperability of legal XML documents.

Focusing on Web 2.0

I assume that because big publishers have their own standards that depend on their business processes, they are not very interested in a new metadata standard. I am convinced that the largest audience for a new metadata standard can be found in the Web 2.0 community.

A lot of incredibly good and interesting legal web projects are driven by hundreds, perhaps thousands of people, mostly technically talented lawyers. Here are some examples from the German websphere:

- Two students created an open platform for court decisions and law texts;

- A group of students writes articles for other students who are preparing for academic exams;

- Two law students have created a very interesting project that allows others to create and share legal mindmaps; and

- In the directory http://fjip.de, we can find approximately 400 known German law projects (with more being added each week), all accessible free of cost.

Connecting contents

What might happen if these Web 2.0 projects were able to share information about their content by automatically linking to each other? Consider this hypothetical use case: On http://juraexamen.info, you read an interesting legal article. The article talks about a court decision that is very important for your subject. The reference number of the court decision is automatically generated as a link that brings you directly to the court decision itself on http://openjur.de. There, a preview of a mindmap from http://www.juralib.de/ is shown, that uses a visualization to put the court decision in a global context.

Legal information is eminently suitable for being identified automatically at the document or subdivision level, by an identifier, such as paragraph number, a citation to a journal article, or a reference number of a court decision. These identifiers can take the form of primary keys, and can automatically be referenced from and to other documents. For big publishers of online databases, such functionalities have been common for many years.

These functionalities — configurable, automatically generated, and updated by implemented jurMeta tools — would dramatically increase the value of each legal content site. And a positive side effect will be a higher page-rank for these sites, because of deep links. The links between the different sites and the exchange of metadata can be supported by modules written for the different content management systems. A community could develop such modules. First, however, many questions have to be solved, some of them very important structure-related decisions. For example: will there be a central jurMeta repository on http://jurmeta.de with metadata links, or will the system be completely decentralized? I’m looking forward to a lot of discussion about this.

Considering business models

Everybody who shares legal knowledge for free on the Web is strongly motivated to do so, and most such organizations — which are often run on a non-profit basis — utilize business models. For example, typically, a blogger’s business model is to design a personal brand and to gain a reputation as being knowledgeable in his or her field. In my opinion, supporting free access to law services’ business models with standards, and the tools necessary to implement those standards, offers the best chance for a project like jurMeta to become well established.

The following two short examples demonstrate how linking documents via jurMeta can benefit free access to law services, irrespective of their business models:

- If the business model of a website is to earn money with advertising, linking metadata must bring the users to the website’s pages. If metadata fail to do that, nobody will see the ads and the goals of the website creator will remain unachieved.

- If the business model is to gain reputation, metadata could be linked — in an AJAX popup, for example — on the condition that the author is named or the author’s photo is shown.

I am absolutely sure that one can identify many ways in which jurMeta can support a certain set of business models commonly employed by free access to law services. I believe that such support is a prerequisite for the broad acceptance of jurMeta.

Because jurMeta is still in development, we can’t yet provide detailed technical specifications for it. Our highest priority for a jurMeta metadata standard is to allow others to build tools on top of it. Therefore, jurMeta will be a simple standard, following the Pareto principle: gaining 80% of the possible effect by only 20% of the necessary investment.

So far I have developed the tagset and labels that I need for the internal document processing of our search engine, kjur.de. The actual tagset can be found on http://jurmeta.de. In general, I propose to follow most of the rules and principles of Dublin Core, but with law-specific labels. In my opinion, it is very important that no tags or terms of jurMeta be mandatory. Everything is optional. The tools of jurMeta have to prove that people really benefit from annotating metadata.

Here is an example with some labels of the current jurMeta syntax. In HTML, jurMeta tags look like this:

<meta name=”jm.doctype” content=”court decision”>

<meta name=”jm.courtname” content=”Bundesgerichtshof”>

<meta name=”jm.filenumber” content=”VIII ZR 316/06”>

<meta name=”jm.fieldoflaw” content=”Mietrecht”>

<meta name=”jm.keyword” content=”Endrenovierung”>

Here these labels appear in XML encoding with an embedded related document:

<jm:document>

<jm:doctype>court decision</jm:doctype>

<jm:courtname>Bundesgerichtshof</jm:courtname>

<jm:filenumber>VIII ZR 316/06</jm:filenumber>

<jm:fieldoflaw>Mietrecht</jm:fieldoflaw>

<jm:keyword>Endrenovierung</jm:keyword>

<jm:related><jm:document>

… another XML-document with jurMeta XML …

</jm:document></jm:related>

</jm:document>

I also think of variations of jurMeta in microformat (using the “rel” tag) and RDF. The technical details have to be worked out during the next few months so that we can have a first beta release of jurMeta this year, perhaps at the next EDV-Gerichtstag in September 2010.

I invite everyone to further discussion of this subject here in this blog or on http://jurmeta.de!

[Editor’s Note: Other current applications of Dublin Core metadata to legal materials include:

- The LII‘s OAI4Courts and Suggested Metadata Practices for Legislation and Regulations;

- John Joergensen‘s metadata for legislative documents and law journal articles; and

- Prof. Dr. Maarten Marx‘s metadata for parliamentary documents.

Further, Olivier Charbonneau discusses an automatic link generating system for free access to law services in this post, and Ivan Mokanov discusses CanLII‘s partial implementation of such a system in this post.]

Dipl.-Jur. Felix Zimmermann is CEO and lead developer of http://kjur.de, a legal search engine. He is legal assistant at the law firm Kehr – Ritz & Kollegen in Hannover, Germany. In the past he has worked as research associate at the Institute of Legal Informatics of the Leibniz University of Hannover (Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kilian) and at the Institute of Security and Security Law of the University of Passau (Prof. Dr. Dirk Heckmann).

Dipl.-Jur. Felix Zimmermann is CEO and lead developer of http://kjur.de, a legal search engine. He is legal assistant at the law firm Kehr – Ritz & Kollegen in Hannover, Germany. In the past he has worked as research associate at the Institute of Legal Informatics of the Leibniz University of Hannover (Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kilian) and at the Institute of Security and Security Law of the University of Passau (Prof. Dr. Dirk Heckmann).

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor in chief is Robert Richards.