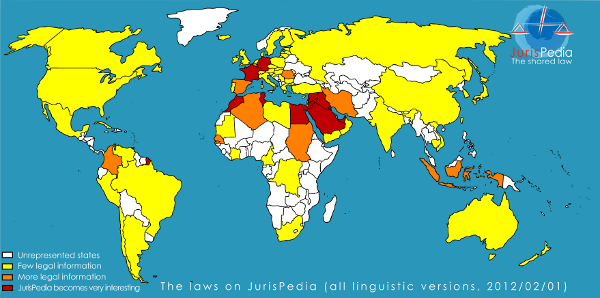

JurisPedia, the shared law, is an academic project accessible on the Web and devoted to systems of law as well as legal and political sciences throughout the world. The project aims to offer information about all of the laws of every country in the world. Based on a Wiki, JurisPedia combines the facility of contributions on that platform with an academic control of those insertions a posteriori. This international project is the result of a free collaboration of different research teams and law schools[1]. The different websites are accessible in eight languages (Arabic[2], Chinese, Dutch, English, French, German, Spanish and Portuguese). In its seven years of existence, the project has grown to more than 15000 entries and outlines of articles dealing with legal systems of thirty countries.

In 2007, Hughes-Jehan approached my colleagues and I, then running the Southern African Legal Information Institute, to host the English language version of JurisPedia. We were excited at the opportunity to work with JurisPedia to introduce the concept of crowdsourcing legal knowledge to Anglophone universities, where we hoped the concept would fall on fertile ground amongst students and academics.

Any follower of the Wikipedia story will know that the reality is not as simple.

Wikipedia operates on 5 pillars:

- Wikipedia is an online encyclopedia;

- Wikipedia is written from a neutral point of view;

- Wikipedia is free content that anyone can edit, use, modify, and distribute;

- Editors should interact with each other in a respectful and civil manner;

- Wikipedia does not have firm rules.

In adopting the Wikimedia software, JurisPedia would appear to follow the same principles. There is a significant difference: JurisPedia is not written from a neutral point of view but from a located point of view. Each jurisdiction has a local perspective on their legal concepts. Jurispedia aims to represent the truth in several languages: the law is as it is in a country, not as it could or should be. As a result, we have the bases of a legal encyclopedia representing over 200 legal systems where each concept is clearly identifiable as a part of a national law.

Southern African Perspectives

As for Wikipedia, it is the third pillar which seems to strike terror into the hearts of the legal professionals and academics with whom I have spoken.

When describing the idea to one of the trustees of SAFLII, an acting judge on the bench of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, I was alerted to some difficulties that may lie ahead. She is an exceptional, open-minded and forward-thinking legal mind, but she was cautiously horrified at the prospect of crowdsourced legal knowledge. Her concerns, listed below, were to be echoed by the deans of law schools in South Africa who we approached:

- Because there is no formal control over submissions – and therefore their accuracy – JurisPedia cannot be used by students as an official reference tool. Citations linking to JurisPedia will not be accepted in student papers.

- Crowdsourced legal information, particularly in common law jurisdictions, runs a high risk of providing an incorrect interpretation of the law.

The overarching concern appears to be that if legal content is made freely available for editing, use, modification and distribution, that the resulting content will be unreliable at best and just plain wrong at worst.

After 7 years online though, there is a substantial amount of feedback about contributors to the project. The open nature of this law-wiki, to which every internet user can contribute, did not lead to a massive surge of uncontrolled and uncontrollable content. On the contrary, although the number of articles continues to grow, it remains reasonable. The subject of the project (only the law), and its academic character has certainly led to a auto-selection of contributors of a higher caliber in legal studies. Many of the contributors are students doing a master or a Ph.D. degree, but they also include doctors, professors and professionals in law, such as lawyers, notaries and judges from more than thirty jurisdictions (and one member of parliament from the Kingdom of Morocco). All these specialists give the project a solid foundation and make it a reality by contributing from time to time as they can. More than 19000 users have subscribed to JurisPedia, and in the past year, more than 1000 people, from Arabic language countries for most part, joined its facebook group.

The JurisPedia content is licensed under a Creative Commons licence that is quite customisable so that the content can be reused for purposes other than commercial purposes. This last point is linked to the authorization of the particular contributor. This is a fair choice in the information society where the digital divide is an important element concerning every international project on the internet: for now, only the most developed jurisdictions have the possibility of using such collective creations in a commercial way. And we take pride in counting contributors from Haiti or Sudan (if you want to use commercially the informations they provide, please, contact them…)

In this context concerns regarding the integrity of the content of JurisPedia become less alarming.

However, I believe that these concerns also represent a misconception of what JurisPedia is and what it can be in the Anglophone, common law, legal context.

Occasionally, it is easier to understand what something is by describing what it is not. JurisPedia is not:

- A law report

- A law journal

- A prescribed legal text book

- A law professor

- A judge

- A lawyer

Let us imagine for a moment that JurisPedia is also not an online portal but a student tutorial group, led by a masters student, an associate or full professor. In the course of the tutorial, a few ideas are put forward, discussed, dissected and amended. Each student (in an ideal world!) leaves the group with a better understanding of a particular point of law which has been discussed. Perhaps the person leading the group has also had occasion to review his or her own position. The group dispurses to research the work further for a more formal submission or interaction.

Now let us imagine that a lay person struggling with a specific legal problem related to what the group has been discussing, is allowed a final, précised description of the law relating to this legal problem prepared by this tutorial group. He or she cannot head into a courtroom armed only with this information, but it may allow them to engage with a legal clinic or lawyer feeling a little less lost.

The thought experiment I describe above describes the read-write meme applied to the legal context. In this meme we encourage an involvement in sharing knowledge amongst legal professionals, academics and students in order to create a body of knowledge about the law accessible by the same as well as by the general public.

The risk of inaccuracies is present in all contexts, printed and online, crowdsourced or expert. A topic for a further blog may be the review of perceived versus actual risk but I would like to use this blog post to propose that the actual risk of inaccuracies can be mitigated by one of two approaches I have considered:

- a more active engagement by the legal community and academics in the form of editorial committees; or

- through the incorporation of JurisPedia into academic curricula.

My immediate concern with the idea of an editorial committee is that we then begin to morph JurisPedia into what it is not. However, if we can teach students of the law to understand how JurisPedia can be used, and how the concept of self-governance can be applied, then we have created a community of lawyers equipped to deal with a world in which there is some wisdom to the crowds.

The English version of JurisPedia is now hosted by AfricanLII, a project started by some of SAFLII’s founding members and now run as s project of the Southern Africa Litigation Centre. As AfricanLII, we want to help build communities around legal content. We believe that encouraging commentary on the law increases the participation of the people for whom the law is intended and therefore helps to shape what the law should be. JurisPedia represents an angle on this: informed submissions by members (or future members) of the legal community. I have described what JurisPedia is not and alluded to what it could be by way of a thought experiment. I propose that we see JurisPedia as an access point. It may be an access point for a student to assist them to understand a point of law that is opaque to them (including references for further reading); or it may be a way for a lay person to understand a point of law which is currently impacting their lives.

JurisPedia represents a mechanism for bringing relevance in today’s social context to the law. How it is used should be considered creatively by those who could potentially benefit from the legal information diaspora of which it is a part.

Global Perspectives

From the global perspective, JurisPedia gives information about Japanese and Canadian constitutional law in Arabic, information about Indonesian, Ukranian and Serbian law in French. It also gives information about experiments like the “legislative theatre”, born in Brazil and experimented with by actors in France and several other countries. JurisPedia is an international project that should follow some simple and unifying guidelines. This is why we tried from the beginning to eliminate any geographical centralization (in order to inform about law as it is and not as it should be in a certain state). The observation of law in the world is not necessarily connected to the idea of a universal legal system, and – since we like to highlight evidence – law is linked to its culture and can be either more or less[3] similar to our own legal system.

Further, one of the latest enhancements to JurisPedia provides access to the law of 80 countries, by using Google Custom Search on a preselection of relevant websites (see family law in Scotland).

This is why shared law becomes not only a program preventing anybody from ignoring a legal system. On the contrary, JurisPedia will gradually make it possible to appreciate or react to what is done elsewhere, not only in the West but also in the North, East and South[4].

[1] Actually: the Institut de Recherche et d’Etudes en Droit de l’Information et de la Communication (Paul Cézanne University, France); the Faculty of Law of Can Tho (Vietnam); the Faculty of Law at the University of Groningen (Netherlands); the Institute for the Law and Informatics at the Saarland University (Germany); Juris at the Faculty for political and legal sciences at the University of Quebec in Montreal. This list is not definite, the project being absolutely open, especially to research teams and Faculties of Law of southern states.

[2] This arabic version of JurisPedia (جوريسبيديا ) is most of the time managed by Me Mostafa Attiya, member of the Egyptian Bar Association. He made an amazing job and actively participated to build a large arabian legal community on the project.

[3] An animal is often considered to be a movable property. This can be absurd in some societies where the alliance between human and nature is different. History and literature told us often about this kind of astonishment when cultures observe each other (see, concerning criminal law and 900 years ago, Maalouf, Amin. The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, New York: Schocken Books, 1984. (concerning the trials by ordeal during the Frankish period.)

[4] This part was written in Europe…

Hughes-Jehan Vibert is a doctor of Law from the former IRETIJ (Institute of research for the treatment of the legal information, Montpellier University, France) and a research fellow in the Institute of Law and Informatics (IFRI, http://www.rechtsinformatik.de, Germany). He’s ICT project manager for the Network for Legislative Cooperation between the Ministries of Justice of the European Union and also working on a report about the diffusion and access to the law for the International Organization of the Francophonie.

Hughes-Jehan Vibert is a doctor of Law from the former IRETIJ (Institute of research for the treatment of the legal information, Montpellier University, France) and a research fellow in the Institute of Law and Informatics (IFRI, http://www.rechtsinformatik.de, Germany). He’s ICT project manager for the Network for Legislative Cooperation between the Ministries of Justice of the European Union and also working on a report about the diffusion and access to the law for the International Organization of the Francophonie.

Kerry Anderson is a co-founder of and coordinator for the African Legal Information Institute, a project of the Southern Africa Litigation Center. She has worked variously in web development, research and strategy for an advertising agency, IT startups and financial services corporates.She has a BSc in Computer Science from UCT and an MBA from GIBS. Her MBA dissertation was on the impact of Open Innovation on software research development clusters in South Africa.

Kerry Anderson is a co-founder of and coordinator for the African Legal Information Institute, a project of the Southern Africa Litigation Center. She has worked variously in web development, research and strategy for an advertising agency, IT startups and financial services corporates.She has a BSc in Computer Science from UCT and an MBA from GIBS. Her MBA dissertation was on the impact of Open Innovation on software research development clusters in South Africa.

[Editor’s Note: For topic-related VoxPopuLII posts please see: Meritxell Fernández-Barrera, Legal Prosumers: How Can Government Leverage User-Generated Content; Isabelle Moncion and Mariya Badeva-Bright, Reaching Sustainability of Free Access to Law Initiatives; and Isabelle Moncion, Building Sustainable LIIs: Or Free Access to Law as Seen Through the Eyes of a Newbie. VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt.

Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed. The information above should not be considered legal advice. If you require legal representation, please consult a lawyer.