Recently, LexUM, SAFLII and friends commenced a global study on Free Access to Law. It poses the pertinent question: is free access to law here to stay? The goal of the project is to produce a best-practices handbook, collect open-access case studies, and publish an online library on the subject. The ultimate aim of all these activities is to enable future free access to law projects to choose best practices and adapt to local contexts that may have more in common than it initially appears.

This April we kicked off the project in the beautiful African bush with three days of introspection, sharing (for the teenage LIIs) and learning (for the toddler LIIs).

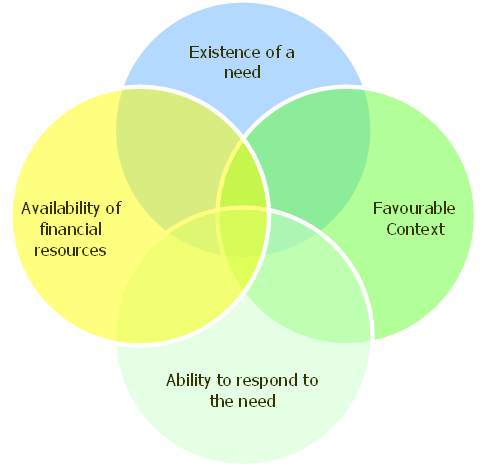

The project seeks to study and link two central concepts – the concept of success of a free access to law project and the concept of sustainability. Ivan Mokanov, who wrote the original project proposal, puts forward a simple thesis that relates the two:

By making law freely available, a legal information institute (LII) produces outcomes that benefit its target audience, thereby creating incentives among the target audience or other stakeholders to sustain the LII’s ongoing operations and development.

Linking free delivery of legal information to core benefits such as support for the rule of law, open and accountable government and the importance of reducing insecurity in economic life can be difficult. Defining the subtler aspects of success thus involves exploration and new methodologies.

In a broad definition, sustainability is seen as the ability to deliver services that provide sufficient value to their target audience, so that either that audience or other stakeholders acting on its behalf choose to fund the ongoing operation and evolution of that service.

The project looks at a sustainability chain:

The words and brilliant logic of fictional psychopath Hannibal Lecter to Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs might serve as a guide to the sustainability chain:

First principles, Clarice. Simplicity. Read Marcus Aurelius. Of each particular thing ask: what is it in itself? What is its nature? What does he do, this man you seek?

The Need

Start with a need or a problem which a LII has to address. An often seen example in my part of the world is a country completely lacking any structures for providing legal information, even commercial print publishers. Sometimes, too, legal information is available, and sometimes freely so, via official printers, government bodies or other creators of the information, but that availability does not necessarily equate to usability.

Different stages of development highlight different needs, and the sustainability chain gives equal weight to addressing each. A free access to law project is just as successful if it manages to provide up=to-date information to judges who until recently applied the law from their 1970s law school textbooks as it is if it provides a state-of-the-art point in time legislation service to practicing lawyers. There seems to be an agreement that, as it grows through its stages of development — as Tom Bruce kindly defined them: establishment, incubation and “going concern” — a sustainable LII closes a chapter of success and continues on to respond to a new need within its target audience.

The Environment

The context in which an LII operates is equally important in determining the success and subsequently the sustainability of a free access to law operation. An LII will thrive in an environment that provides rich data sources, and is amenable to and capable of reform and change, with a policy and legal framework favourable to the free dissemination of legal information. To bring this to the nitty-gritty level – a free access to law project needs support all the way from the political top down to the secretary and clerk of the court.

An important environmental indicator is the availability of an infrastructure to support circulation of information. LIIs operating in developing countries often face the roadblock of lack of technology or lack of knowledge of the use of technology at the source. While computers have made their way into most judges’ chambers and courtrooms, most are not connected to the Internet, or if they are, the connections are so slow as to bar convenient use. A judge once relayed that in the rural areas, courts, well-computerized using donor money, are unable to make use of the technology due to lack of electricity. It is not unheard of a clerk or court secretary to delete judgments from a computer once they have been printed, thus leaving one single hard copy of a judgment for the court files.

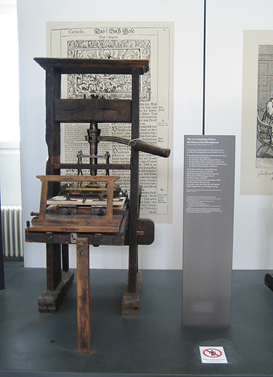

Developing countries’ LIIs, as aptly pointed by my colleague Kerry Anderson in a post below, often involves getting information from this:

|

into this |  |

This inevitably begs a couple or more open questions for a “toddler” LII:

Who should foot the bill for the expensive digitization of legal material?

It has been the norm since the Middle Ages that the rulers of the land make the laws known to the subjects and citizens (I tend to include lawyers and government officials in the plebs) . But — assuming that it even recognizes this obligation, as the government of South Africa does — how does a cash-strapped government of a developing country fulfill its obligation to do so? Donors donating directly to government to set up law reporting or print legislation? Donors via support for a LII? The interested public via support for a LII?

Would a successful strategy for a LII be to, first and foremost, address the policy and technology issues of provision of digital information?

Digitizaion of print materials and/or manual capturing of metadata, for example, cannot be deemed a successful strategy in the long run – it is simply uneconomical to continue to do so past a certain stage. Engaging stakeholders in education of use of technology or development of IT solutions to support workflows for delivering of judgments or passing legislation may be a way of dealing with issues of digitizing and automating delivering of law to the public. Standards of preparation of legal material, such as the ones developed by the Canadian Citation Committee or the endeavours of the Africa i-Parliaments project, adopted by all originators of legal information in a particular jurisdiction, will ease its dissemination and re-use. Campaigning for the passing policy or legislation, such as the PSI Directive, may be another strategy for a LII to enhance the efficacy of its operations.

How does an NGO engage with government over the digitization strategy?

The Ability

The need is recognized, we have a favourable environment for operations. Now, how does a lawyer, frustrated by the lack of user-friendly legal resources, with little to no know-how, convert the circumstances to a successful and sustainable free access to law project?

An LII needs to have the ability to respond to the need for legal information on at least two levels: organizational and technological. At the organizational level, a free access to law project needs to have organizational structure and support that is responds correctly to the context in which the project operates.

What are the benefits of the different organizational structures? Are they dependent on the development stage of an LII?

Among the members of the project’s workshop group, there seemed to be an agreement on the need for any new access to law project to possess adequate technology (in general), and to possess or have access to legal information technology and expertise. The right technological and information-standards choices for particular environments are crucial to the correct response to the audience’s need. While this carries a positive connotation, an emerging free access to law project needs to learn also to respond to user feedback in a measured way, and sometimes to even say NO.

Availability of Financial Resources

This couple-of-hundred-thousand-dollar question is one that every LII – from babies to teenagers – asks every financial cycle. Free access to law is quite expensive. While the product can be free, as in free beer, the process of creating the value and benefit to the audience can be quite expensive.

The ability of any LII to financially plan a few years ahead is crucial to the success of the project. It is important to have an audience that has identified value in a free access to law project – be it lawyers (CanLII and to an extent AustLII), or in addition to the preceeding, advertisers and aligned services (LII), or government (Kenya Law Reports), or international donors (SAFLII) , or individuals and lawyers (OpenJudis). Holding on to an audience and maintaining its willingness to pay relies on maintaining and improving existing product value. It is also crucial that money is spent in the right places.

The Handbook to be produced at the end of this study will identify how successful LIIs allocate budgets, according to value produced and how and who supports creation of specific benefits.

The next 6-8 months

In the next six to eight months the research team consisting of Dorsaf El Mekki (LexUM), Bobson Coulibaly (JuriBurkina, West Africa), Prashant Iyengar (Centre for Internet and Society, India), myself at SAFLII and a number of researchers from Namibia, Uganda, Zimbabwe and Kenya, will endeavour to collect data via interviews, questionnaires, case studies and web statistics on a number of indicators to reinforce the assumptions and prove the hypotheses of the study into free access to law – a study very much needed.

Mariya Badeva-Bright is the Head of Legal Informatics and Policy at the

Southern African Legal Information Institute (SAFLII). She is a

sessional lecturer at the School of Law, University of the

Witwatersrand, South Africa where she teaches the LLM course in Cyberlaw

and the undergraduate course in Legal Information Literacy.

Ms. Badeva-Bright received her Magister Iuris degree from Plovdiv

University, Bulgaria and an LL.M degree in Law and Information

Technology from Stockholm University, Sweden.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt.