Great was the rejoicing in the south tower of Myron Taylor Hall, headquarters of the LII, when we got notice of the bulk release of the Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (eCFR) in XML format.

What was not to like? The data was as up-to-date as the CFR could get, the XML was much cleaner than the book version, it had a friendly user guide etc., etc., etc..

It was also different enough from the book XML of the CFR, that we could not simply run it through our existing data enrichment process and serve it to the public as is. So, we curbed our enthusiasm long enough to put together a measured plan to re-do our code.

We have heard enough from you, our wonderful readers, that text indentation was one of the most valued features of our data presentation. Thus, it was the first feature we chose to implement.

All this verbosity is the set-up for a look at some of the messy sausage making details of adding indentation to the eCFR.

***

If you’re not familiar with XML (eXtensible Markup Language), it’s simply a way of marking up data with a predefined, consistent set of descriptive tags that are both easily human and machine readable. So, when we get XML data from the GPO, it looks something like this…

Snippet 1: XML from Title 1 of the CFR

==============================================

<?xml version=“1.0“ encoding=“UTF-8“ ?>

<DLPSTEXTCLASS>

<HEADER>

<FILEDESC>

<TITLESTMT>

<TITLE>

Title 1: General Provisions</TITLE>

<AUTHOR TYPE=“nameinv“>

</AUTHOR>

</TITLESTMT>

<PUBLICATIONSTMT>

<PUBLISHER>

</PUBLISHER>

<PUBPLACE>

</PUBPLACE>

<IDNO TYPE=“title“>

1</IDNO>

<DATE></DATE>

</PUBLICATIONSTMT>

<SERIESSTMT>

<TITLE>

</TITLE>

</SERIESSTMT>

</FILEDESC>

<PROFILEDESC>

<TEXTCLASS>

<KEYWORDS>

</KEYWORDS>

</TEXTCLASS>

</PROFILEDESC>

</HEADER>

<TEXT>

<BODY>

<ECFRBRWS>

<AMDDATE>Jan. 30, 2015</AMDDATE>

<DIV1 N=“1“ NODE=“1:1“ TYPE=“TITLE“>

<HEAD>Title 1 – General Provisions–Volume 1</HEAD>

<CFRTOC>

<PTHD>Part </PTHD>

<CHAPTI>

<SUBJECT><E T=“04“>chapter i</E> – Administrative Committee of the Federal Register </SUBJECT>

<PG>1</PG></CHAPTI>

<CHAPTI>

<SUBJECT><E T=“04“>chapter ii</E> – Office of the Federal Register </SUBJECT>

<PG>51</PG></CHAPTI>

<CHAPTI>

<SUBJECT><E T=“04“>chapter iii</E> – Administrative Conference of the United States </SUBJECT>

<PG>301</PG></CHAPTI>

<CHAPTI>

<SUBJECT><E T=“04“>chapter iv</E> – Miscellaneous Agencies </SUBJECT>

<PG>425

</PG></CHAPTI></CFRTOC>

<DIV3 N=“I“ NODE=“1:1.0.1“ TYPE=“CHAPTER“>

<HEAD> CHAPTER I – ADMINISTRATIVE COMMITTEE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER</HEAD>

<DIV4 N=“A“ NODE=“1:1.0.1.1“ TYPE=“SUBCHAP“>

<HEAD>SUBCHAPTER A – GENERAL

</HEAD>

<DIV5 N=“1“ NODE=“1:1.0.1.1.1“ TYPE=“PART“>

<HEAD>PART 1 – DEFINITIONS </HEAD>

<AUTH>

<HED>Authority:</HED><PSPACE>44 U.S.C. 1506; sec. 6, E.O. 10530, 19 FR 2709; 3 CFR, 1954-1958 Comp., p.189.

</PSPACE></AUTH>

<DIV8 N=“§ 1.1“ NODE=“1:1.0.1.1.1.0.1.1“ TYPE=“SECTION“>

<HEAD>§ 1.1 Definitions.</HEAD>

<P>As used in this chapter, unless the context requires otherwise – </P>

<P><I>Administrative Committee</I> means the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register established under section 1506 of title 44, United States Code; </P>

<P><I>Agency</I> means each authority, whether or not within or subject to review by another agency, of the United States, other than the Congress, the courts, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the territories and possessions of the United States; </P>

<P><I>Document</I> includes any Presidential proclamation or Executive order, and any rule, regulation, order, certificate, code of fair competition, license, notice, or similar instrument issued, prescribed, or promulgated by an agency; </P>

<P><I>Document having general applicability and legal effect</I> means any document issued under proper authority prescribing a penalty or course of conduct, conferring a right, privilege, authority, or immunity, or imposing an obligation, and relevant or applicable to the general public, members of a class, or persons in a locality, as distinguished from named individuals or organizations; and </P>

<P><I>Filing</I> means making a document available for public inspection at the Office of the Federal Register during official business hours. A document is filed only after it has been received, processed and assigned a publication date according to the schedule in part 17 of this chapter.</P>

<P><I>Regulation</I> and <I>rule</I> have the same meaning. </P>

<CITA TYPE=“N“>[37 FR 23603, Nov. 4, 1972, as amended at 50 FR 12466, Mar. 28, 1985]

</CITA>

</DIV8>

</DIV5>

…

…

…

</DIV1>

</ECFRBRWS>

</BODY>

</TEXT>

</DLPSTEXTCLASS>

The text of the regulations are enclosed within tags that provide some context for what you’re looking at, have meaning for how it should be displayed or provide additional metadata that may be useful to the enrichment process.

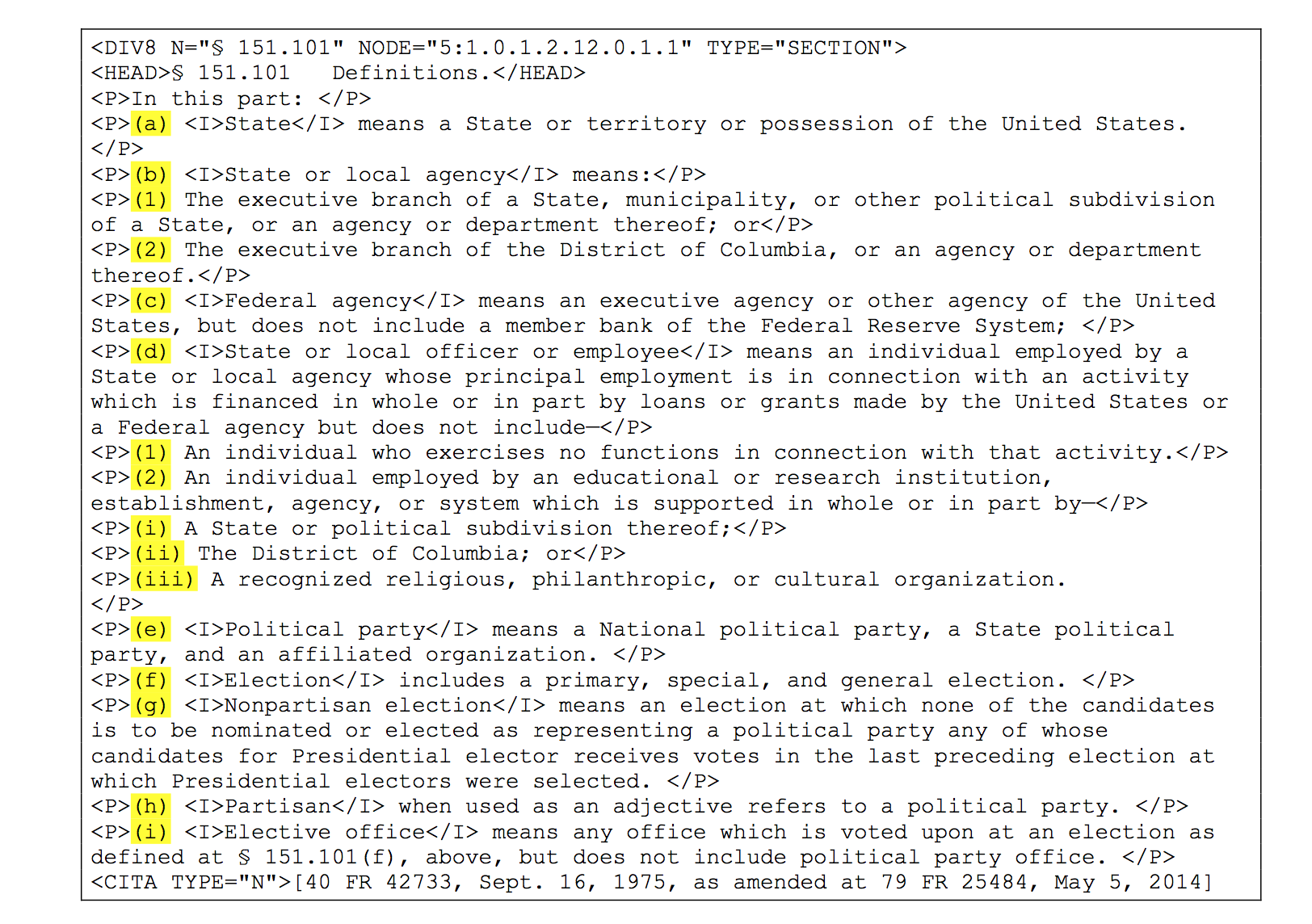

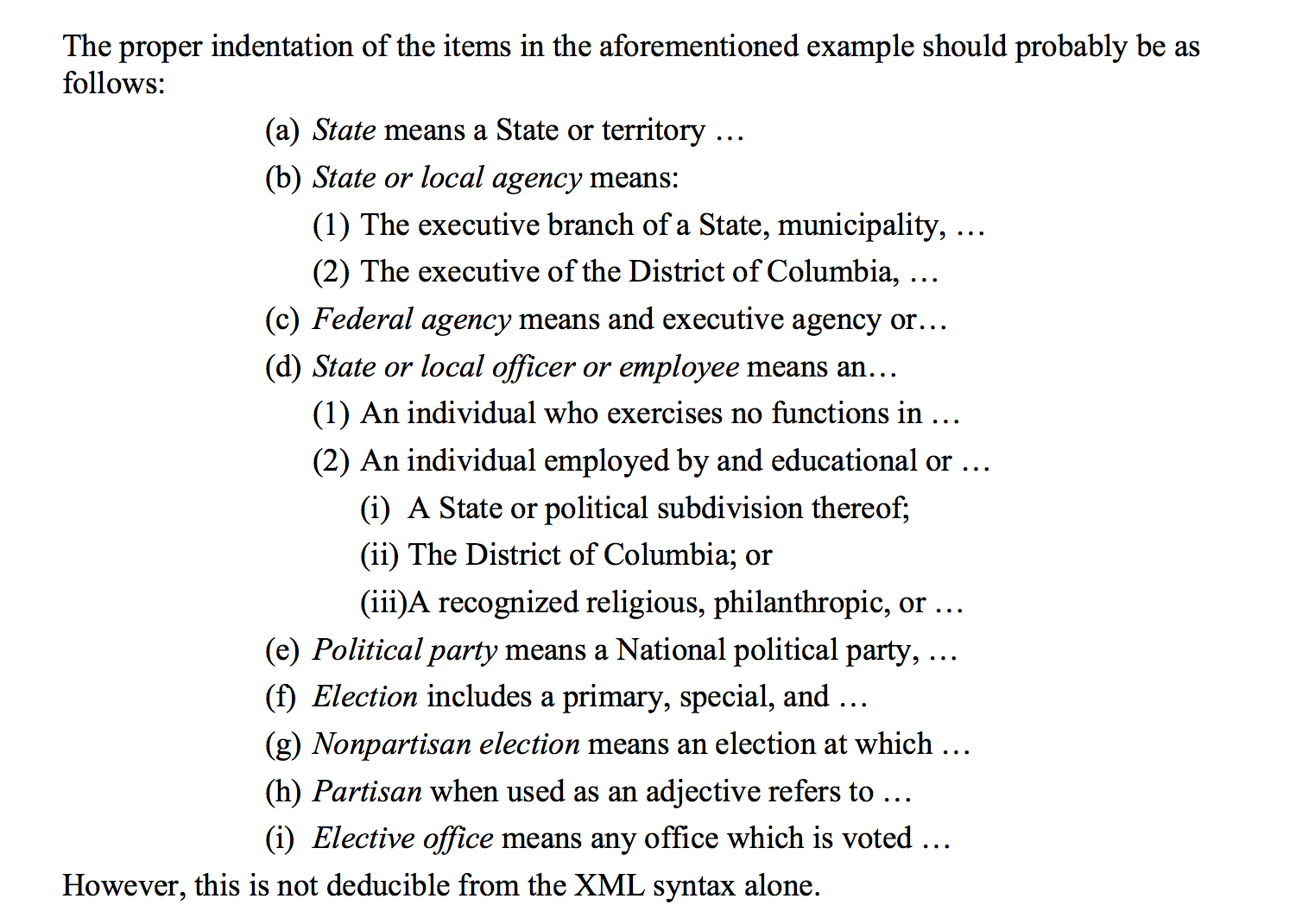

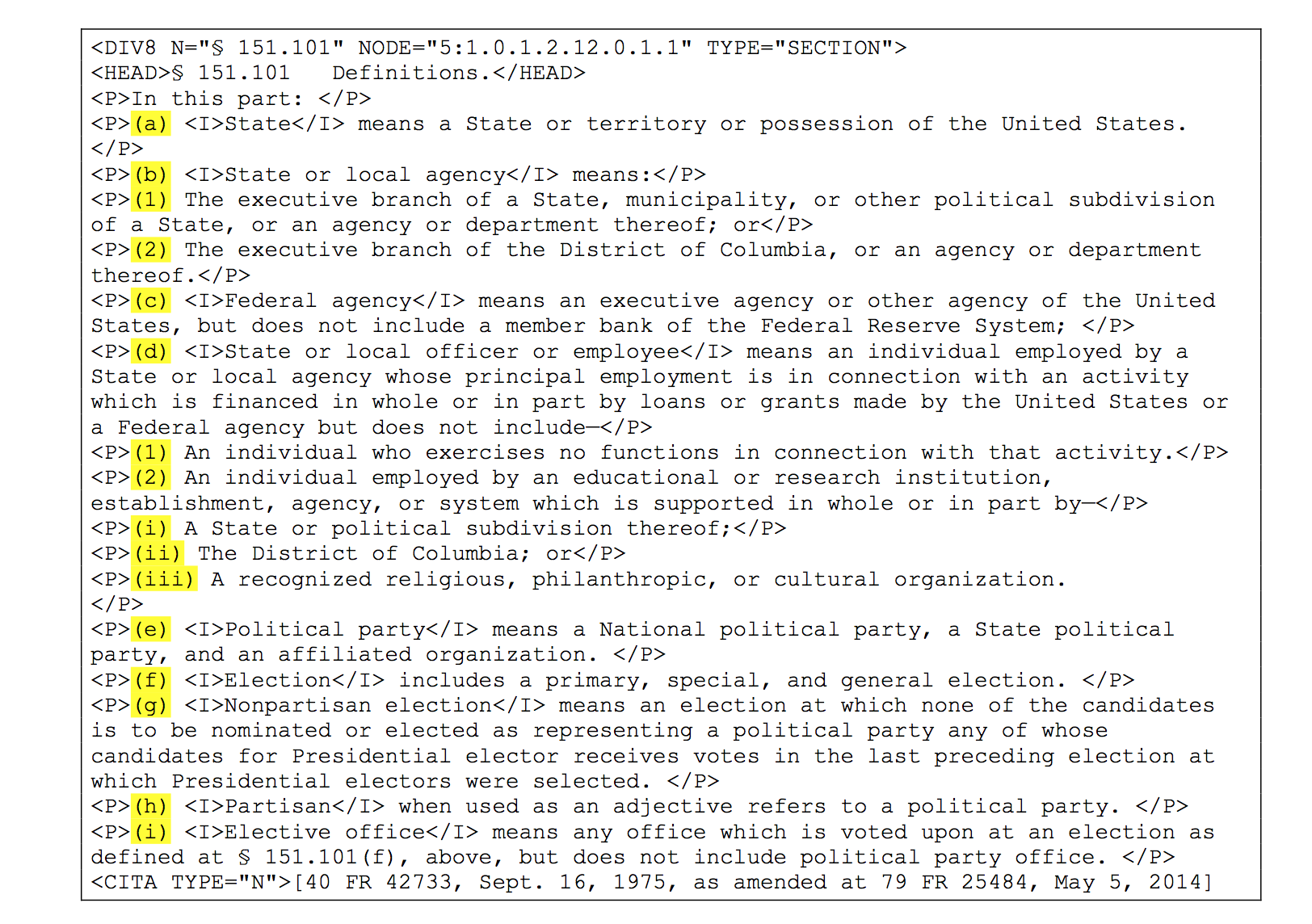

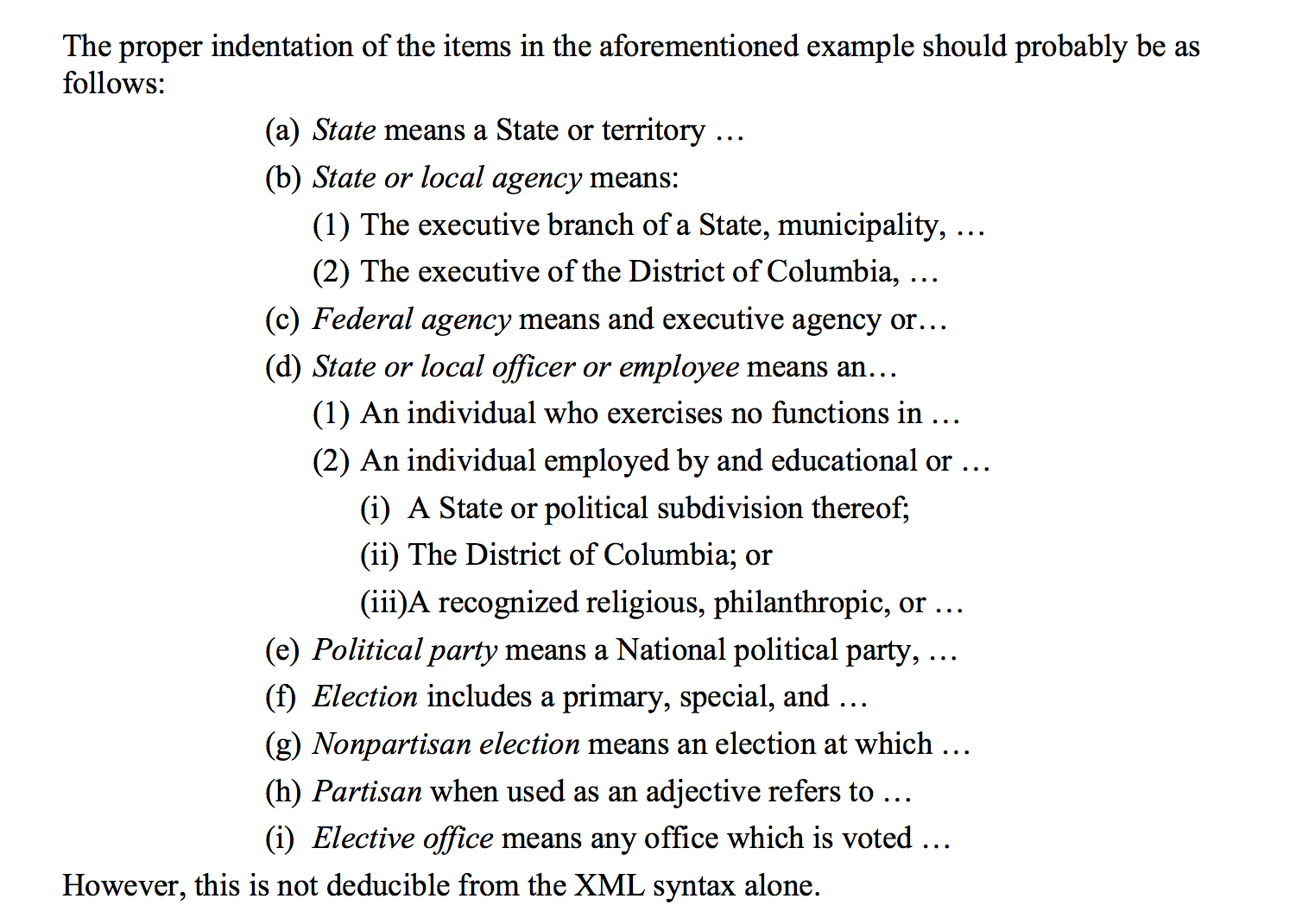

As a first step, we consulted the user guide to see if there was any information on how to indent the text. There was something! On page 13, was this snippet of XML (Figure 1) with the enumeration indicators highlighted. The next page had a suggestion for how that could be displayed (Figure 2).

Obvious to us and as indicated by the user guide itself, there was no way to achieve this display given just the information from the markup. A good place to look for extra information was within the CFR itself.

We found what we were looking for in Title 1, Section 21.11, which is about how the CFR enumerators are organized, or more accurately, are supposed to be organized. Of particular interest was the hierarchy of paragraphs given by subsection 21.11(h):

(h) Paragraphs, which are designated as follows:

level 1(a), (b), (c), etc.

level 2(1), (2), (3), etc.

level 3(i), (ii), (iii), etc.

level 4(A), (B), (C), etc.

level 5(1), (2), (3), etc.

level 6(i), (ii), (iii), etc.

In our first iteration of indentation, we added attributes to each paragraph defining a depth of indentation corresponding to the 6 levels above. Section 151.101 of Title 5, the example in the user guide pages above, looked lovely. But, (you knew it would not be that simple, right?) this implementation worked fine for only about 60% of the random selection of sections we tested it on.

Where the algorithm did not work, the main reason for failure was the presence of multiple enumerators within a single paragraph. In other words, each enumerator should have its own paragraph but not all paragraphs were marked as such.

Snippet 2: XML from 9 CFR 2.1

==============================================

<p>(a)(1) Any person operating or intending to operate as a dealer, exhibitor, or operator of an auction sale, except persons who are exempted from the licensing requirements under paragraph (a)(3) of this section, must have a valid license. A person must be 18 years of age or older to obtain a license. A person seeking a license shall apply on a form which will be furnished by the AC Regional Director in the State in which that person operates or intends to operate. The applicant shall provide the information requested on the application form, including a valid mailing address through which the licensee or applicant can be reached at all times, and a valid premises address where animals, animal facilities, equipment, and records may be inspected for compliance. The applicant shall file the completed application form with the AC Regional Director. </p>

In the snippet above, we have the case where there are 2 enumerators at the beginning of the paragraph. Since our algorithm assumed one enumerator per paragraph, it would only find (a) but not (1). We fixed that in the second iteration.

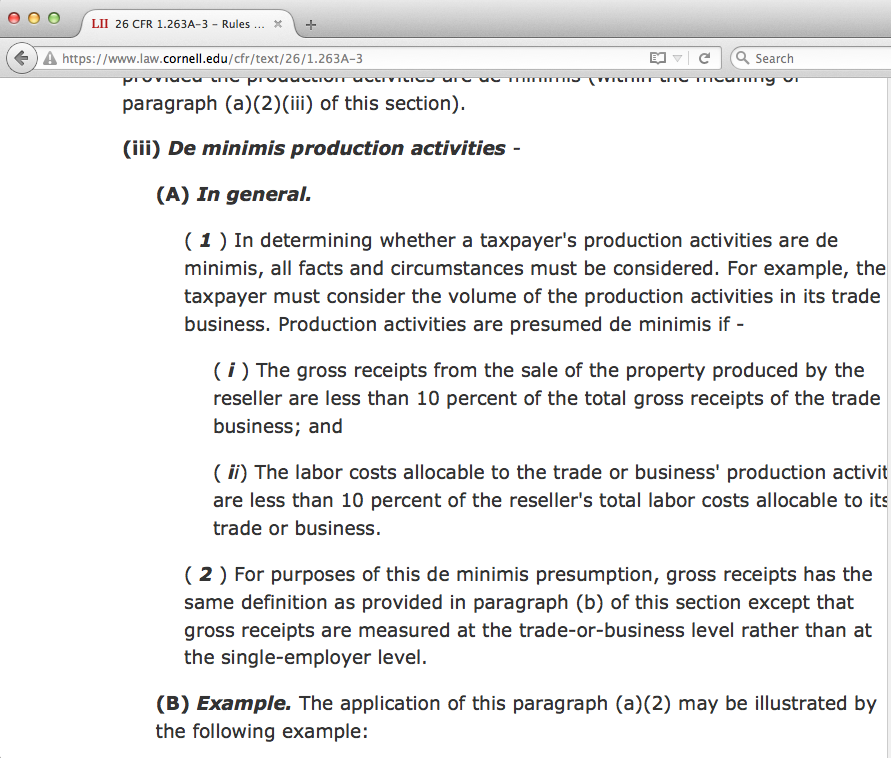

In our third iteration, we went after more embedded enumerators (see snippet 3 below) by creating a category for these previously untagged enumerators. We named them, nested paragraphs, and tagged them as such.

Snippet 3: XML from 8 CFR 103.3

==============================================

<p>(a) <i>Denials and appeals</i> – (1) <i>General</i> – (i) <i>Denial of application or petition.</i> When a Service officer denies an application or petition filed under § 103.2 of this part, the officer shall explain in writing the specific reasons for denial. If Form I-292 (a denial form including notification of the right of appeal) is used to notify the applicant or petitioner, the duplicate of Form I-292 constitutes the denial order.</p>

In the last snippet, the paragraph has 3 enumerators, (a), (1), and (i). We’ve developed a library of patterns that our algorithm uses to find them all. In title 26 alone, we find and tag 13,563 nested paragraphs!

So, we now have a pretty nice indentation feature, that while not completely finished, is already an improvement over what we were able to do before for the CFR. See 8 CFR 103.3 (a)(1)(iii)(A) and its corresponding eCFR version for an example of this.

We’re putting it on the back burner for now but there is more to come for indentation. For instance, we know from extensive study of the markup that there are actually 8 levels of nesting to be had, not 6. And, we have to provide special handling for sections that do not follow the numbering scheme in 1 CFR 21.11.

We’re grateful for our beta testers and readers. If you come across places where our current indentation scheme does not work, please let us know. In the interim, we’ll be devoting some brain cycles to adding cross references and other links to the eCFR.