Twenty-five years ago the LII at Cornell showed the world that access to the law via the Internet for all is possible. It is not only possible, but can be cheap, even free. And that “free” can be sustained. It was and continues to be illuminating, even in the remotest places in Africa. The importance of the pioneering work of the LII, as it translates in Africa, is best understood against the background of complete absence of law reports and updated legislation in many African countries.

Before free access to law touched down in South Africa in 1995, legal information was primarily distributed via the duopoly of the commercial legal publishers. Court reporters– usually advocates practicing in the region of the Court, would act as correspondents for the legal publishers. Cases would take months to be printed in the law reports and, due to constraints of the paper medium, heavy filtering could prevent the publication of really interesting cases from courts lower in the judicial hierarchy. Sometimes judgments marked by the presiding judge as reportable would be omitted from publication too. Space in the reports came at a premium – few got in.

This frustrated users of legal information (and most judges, who could not showcase their work and missed out on promotions!). It meant that additional resources were spent on using informal networks for gathering much needed legal information. It also usually meant that only the handful of rich law firms, residing in the major urban areas of the country, had access to court judgments, that gave them advantage in preparing for litigation. Hunting for judgments from fellow colleagues, court registries and court libraries was common-place, as candidate attorneys were sent to the court’s archives to look for precedent. It was not efficient, but often proved effective for those who could afford this kind of information-gathering. Magistrates, judges and government lawyers could not dream of having this kind of information at their disposal. Citizens rarely had a chance to read a full judgment for themselves.

Imagine (remember?) that time! Well, this would still be the situation in South Africa, and most definitely in many other African countries today, if it were not for SAFLII, AfricanLII, and 15 other LII projects across our continent that make the law available to all for free. SAFLII started at the University of the Witwatersrand when the then Head of the Law Library – Ruth Ward, inspired by what Cornell had been doing for the past 3 years, enlisted the help of a law student with an unusual interest in computers to develop a website to host the judgments of the newly created South African Constitutional Court (there was yuuge demand for this material locally and regionally). The Law School later partnered with AustLII to upgrade the software infrastructure, and SAFLII was born, a new member of the Free Access to Law Movement.

In one of a few firsts in the FAL movement, almost exclusively academic until then, SAFLII was acquired and moved to the Constitutional Court of South Africa. I remember some expressed apprehension — what would happen to an independent academic project under government? — but this turned out to be the best move. SAFLII flourished with the backing of the Constitutional Court judges and expanded its content through a partnership with the Southern African Chief Justices Forum. Unprecedented amount of African legal content slowly made its way to the web. LexUM and CanLII helped us a lot with advice on editorial practices and processing content, while Andrew and Philip of AustLII would fly in once or twice a year to work on site to fine-tune the software.

We dreamt of systems the magnitude of AustLII and CanLII, and the sophistication of the LII. But our reality was different. When we were not busy digitizing paper-based content, we were engaged in training our users in electronic legal research. Yet users continued to demand the convenience of digested cases and consolidated legislation. Capacity was hard to come by. Our friends at Kenya Law Reports right about then decided to open access to their (government funded) material. This raised the bar higher – every judge in our network wanted their own Kenya Law.

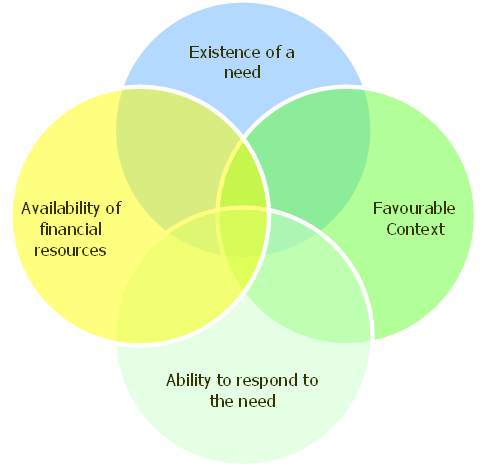

To some extent, this became one of the core reasons for setting up the AfricanLII operation – as a programme that would contextualize the experience our team gathered with developing SAFLII, to help build locally-responsive LII operations. The justice sector in most of our countries of operation was starving for proper legal information – in the vast majority of places there is no regular law reporting or law consolidation, and that affected their work and impacted society and individuals rights sometimes in most adverse ways. Both law revision and law reporting are expensive undertakings, especially when one has to start from scratch. But building a massive materials collection would not be useful if our users could not or would not make use of it. So we had to adapt and with our meager resources – devolve a centralised model (SAFLII) into local operations that allowed for better contextualization of the LIIs.

The proper development of the legal infrastructure, which is what LIIs mostly do in many African countries, means moving at a pace and alongside the overhaul of vital areas of substantive law – human rights, environment, business and commercial law, ICTs and media, all areas developing at a considerable pace in the region. How do we adapt our LIIs to assist this development and remain relevant?

In this sense, I remember during a sustainability workshop discussion with LexUM, the LII and others, back in 2009, Tom Bruce made the point about being strategic in the choices informing our LII development plans. Of course he raised it in his inimitable style – the fable involved something about throwing bottles in an ocean of bottles and the effects of that – but the advice was right on point. When faced with a complete vacuum, as we were with the lack of digital legal information in Africa, the easiest thing to propose and attempt to do is to throw all your available resources at digitizing all information, to serve all potential users out there.

African LIIs, operating with scarce funding and in difficult economic times, are now more than ever orienting towards capitalizing on and further developing the value of the few collections, competencies and advantages that would derive maximum value for their users. Having built a solid base of legal material, we are now looking at arranging it and communicating it in a way that is responsive to the needs of the justice sector. For most LIIs, that would mean digesting (or sourcing interpretative material) legal information and pushing through social media channels with the aim to educate citizens. Or editorializing legal information to serve commercial audiences – and derive income for the LIIs. Or package our LIIs and ship them for off-line use by magistrates working in remote, unconnected areas of Africa. All of this has meant that we’d had to strike a balance and pull resources out of digitization (the ocean of content) and invest in services (new kinds of bottles) that have the potential to sustain our African LIIs into the future.

The LII at Cornell was a pioneer 25 years ago, but Tom, Sara and crew continue to push the envelope – innovating not only technology but also the business of free law. I guess their flexibility and adaptability are some of the reasons why the LII is still going strong and growing 25 years into its existence. And this has been the ultimate lesson for me as I continue to work together with a touch-group of committed individuals across the African continent, forging ahead and cementing their African LIIs into the future of their countries. Our collective hats off to the LII @ Cornell for helping us figure things out along the way!

Mariya Badeva-Bright is the co-founder of the African Legal Information Institute. From 2006 to 2010, she was the head of Legal Informatics and Policy for the Southern African Legal Information Institute (SAFLII). She has taught undergraduate courses in Legal Information Literacy and coordinated the postgraduate program in Cyberlaw at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. She holds a Magister Iuris in law from the Plovdivski universitet “Paisii Hilendarski” in Bulgaria, and an LLM in legal informatics from Stockholm University.