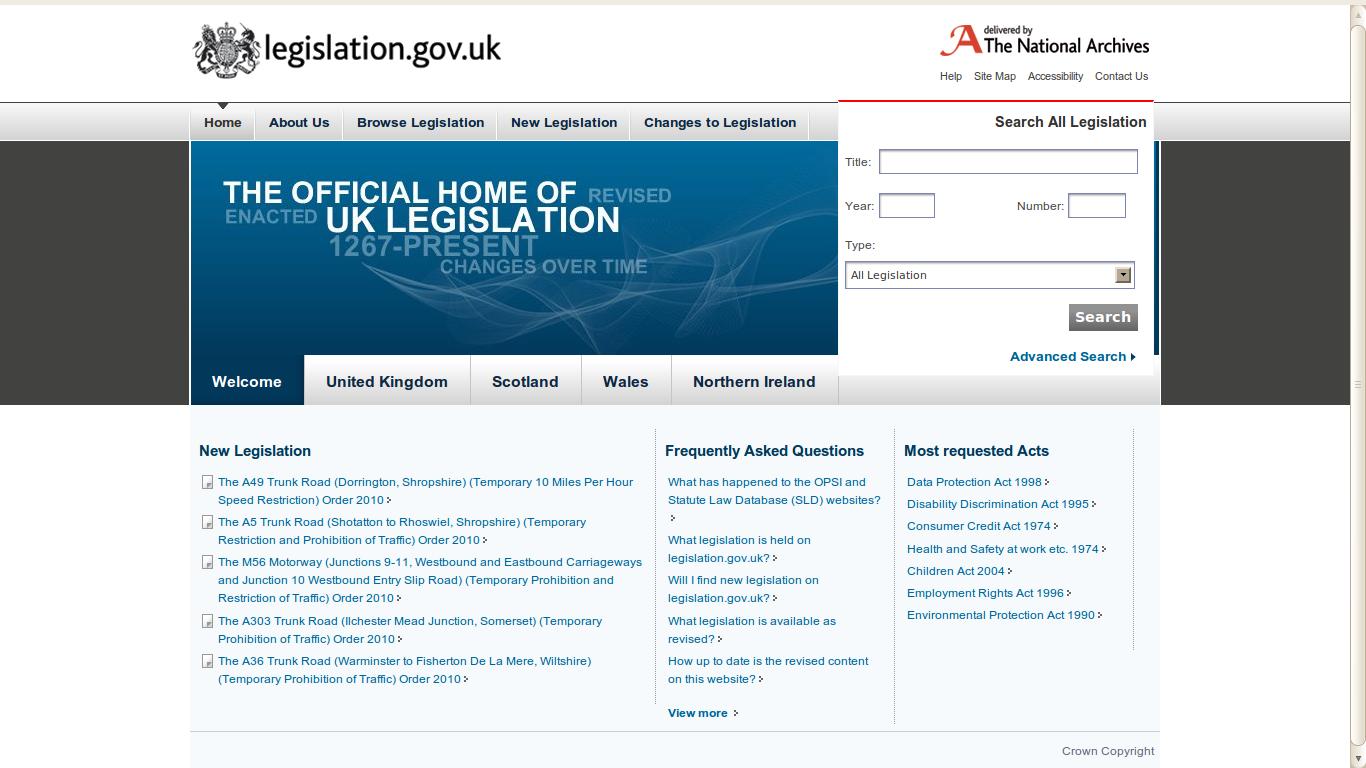

The launch of legislation.gov.uk by The [UK] National Archives marks a step change in public access to a primary source of legal information for citizens in the UK. Legislation.gov.uk is extensive, covering the four jurisdictions that make up the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) and over 800 years of history.

The launch of legislation.gov.uk by The [UK] National Archives marks a step change in public access to a primary source of legal information for citizens in the UK. Legislation.gov.uk is extensive, covering the four jurisdictions that make up the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) and over 800 years of history.

John Sheridan, Head of e-Services and Strategy at The National Archives, writes:

First, some background

We had two objectives with legislation.gov.uk: to deliver a high quality public service for people who need to consult, cite, and use legislation on the Web; and to expose the UK’s Statute Book as data, for people to take, use, and re-use for whatever purpose or application they wish. In particular, our aim was to show how the statute book can contribute to the growing Web of data as well as to the Web of documents.

Legislation.gov.uk replaces two predecessor services the UK government set up to provide access to legislation. The first was created by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO), later to become the Office of Public Sector Information (OPSI), which is responsible for the official publication of legislation, and the London, Belfast and Edinburgh Gazettes. The functions of HMSO have been operating from The National Archives since 2006, including the provision of public access to legislation online. HMSO started publishing new legislation on the Web in 1996. Where HMSO and later OPSI provided access to legislation as it was enacted or made, a second service was developed, to provide access to the UK Statute Law Database. This contains revised versions of primary legislation, showing how they have changed over time.

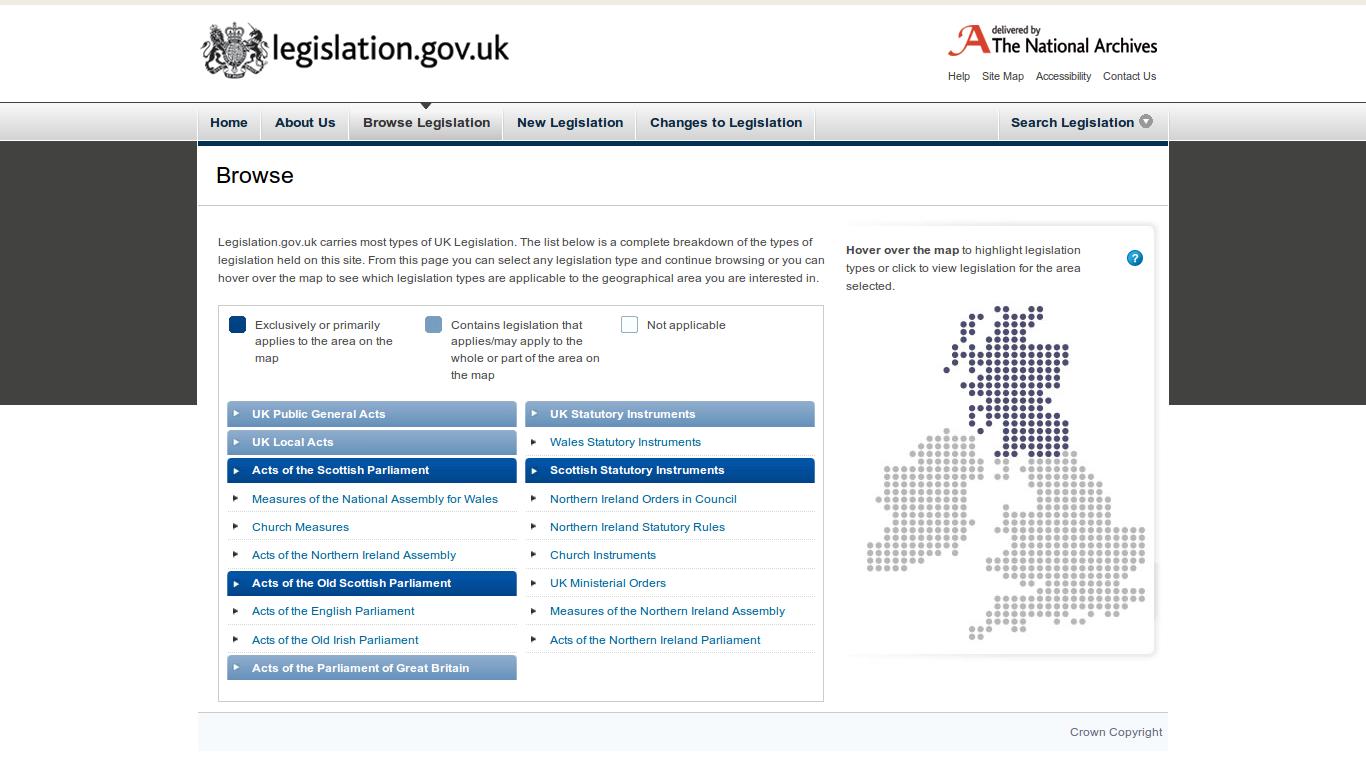

Browsing the many different types of legislation in the UK

As in the United States, most lawyers in the UK rely on pay-for commercial legal research services. The people using the government’s online legislation service are generally not lawyers, but are drawn from a much wider group of people who need to know, cite, or use legislation as part of their job. These can range from police officers, to head teachers, to citizens defending their rights. Our users are people who need to know what a statute says, and who go looking for it using Google. They then quickly find their way to legislation.gov.uk.

What do people think they are seeing?

Before starting work on legislation.gov.uk, we did some research into the users of both the OPSI service and the UK Statute Law Database service. This research showed that they were very well used (over 1.5 million unique visitors per month to www.opsi.gov.uk), but that most of the people accessing legislation on the Web were not clear about the status of the material they were looking at. Our research showed that many people using legislation online assume that what they are looking at is both current and in force, simply because it is on the Web and available from an official source. Often users were accessing the original or as-enacted version of a statute, not knowing that they should be looking at the revised version, or that a revised version even existed.

Intuitive presentation

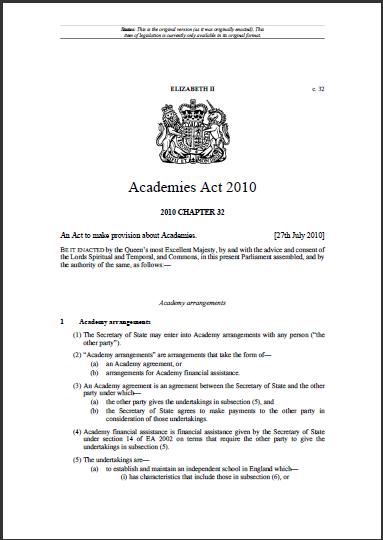

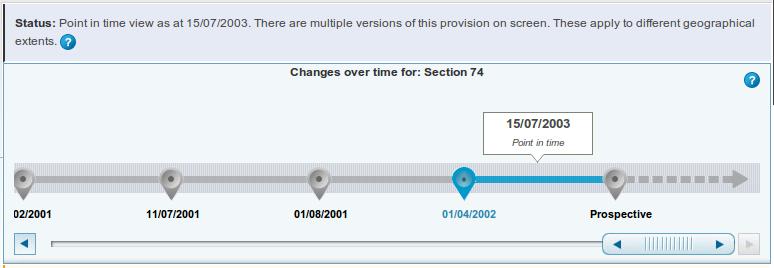

Our job is to present legislative material in such a way that the context and status of the information are clear. Legislation is complicated to understand; for example, an Act may have multiple sections, each with a different commencement date, or the Act may have prospective provisions. With legislation.gov.uk we have tried to develop a user interface that makes the status of each Act clear, so people know whether the statute they are viewing is current and in force. The usability challenge is to align what people think they are seeing with what they are actually looking at. We have done this by presenting both an original (see, e.g., here) and a latest-available version (see, e.g., here) of each Act, and a toggle between the two.

what people think they are seeing with what they are actually looking at. We have done this by presenting both an original (see, e.g., here) and a latest-available version (see, e.g., here) of each Act, and a toggle between the two.

For more advanced users there is a timeline (see, e.g., here) which can be turned on to see how the legislation has changed and to navigate through an Act at particular points in time, including future or prospective versions.

Point in time navigation and the timeline

Open data

On the surface, legislation.gov.uk is an attractive Website, providing simple and direct access to legislation; at legislation.gov.uk people can view whole Acts, or a particular section, in either HTML (see, e.g., here) or in a print version in PDF (see, e.g., here). To achieve this, under the hood two very different sources of data have been combined. The data model for the original (or as-enacted) versions of legislation is largely driven by the typographic layout of legislative documents. For revised legislation, the data model is largely driven by version control, the management of multiple versions of different segments of a statute at different points in time. Reconciling these two different data models was a prerequisite step to developing our system.

We aimed to make legislation.gov.uk a source of open data from the outset. The importance of open legal data is made powerfully by people like Carl Malamud and the Law.Gov campaign. Our desire to make the statute book available as open data motivated a number of technology choices we made. For example, the legislation.gov.uk Website is built on top of an open Application Programming Interface (API). The same API is available for others to use to access the raw data.

Using the API

The simplest way to get hold of the underlying data on legislation.gov.uk is to go to a piece of legislation on the Website, either a whole item, or a part or section, and just append /data.xml or /data.rdf to the URL. So, the data for, say, Section 1 of the Communications Act 2003, which is at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/21/section/1, is available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/21/section/1/data.xml. We have taken a similar approach with lists, both in browse and search results. When looking at any list of legislation on legislation.gov.uk, it is easy to view the data. Simply append /data.feed to return that list in ATOM. (See, e.g., here.)

Open standards have played an important role throughout the development of legislation.gov.uk. All the data is held in XML, using a native XML database. The application logic is similarly constructed using open standards, in XSLTs and XQueries. Data and application portability were key objectives. We made considerable use of open source software like Orbeon Forms, Squid, and Apache.

The XML conforms to the Crown Legislation Markup Language (CLML) and associated schema. More general interchange formats for legislation such as CEN MetaLex lack the expressive power we need for UK legislation, but could relatively easily be wrapped around the XML we are making available. We have sought to surface richer metadata about legislation using RDF, but we would welcome feedback from users of the XML data about whether a MetaLex wrapper would be useful. (Note: We have used the MetaLex vocabulary in our RDF along with FRBR, as discussed below.) Similarly, it should be relatively easy to add a wrapper for the OAI-PMH protocol on top of the API we have built. We are not yet clear who would make use of such a service, if we built one, or whether we should leave the creation of an OAI-PMH interface to others. It is another open issue where we would welcome some feedback.

Persistent URIs

A major influence on legislation.gov.uk was a blog posting by Rick Jelliffe for O’Reilly’s XML.com. Jelliffe writes about something he calls PRESTO. He describes this as a system for legislation and public information in which “all documents, views and metadata at all significant levels of granularity and composition should be available in the best formats practical from their own permanent hierarchical URIs.”

Persistent URIs to pieces of legislation are very important, as they are to sources of law more generally. Initiatives like LegisLink, which Joe Carmel has written about here, attempt to retrofit a reliable naming scheme for legislation onto existing document-based systems. The URN:LEX namespace aims to facilitate the process of creating URIs for legal sources independent of a document’s online availability, location, and access mode.

We wanted to create high quality, persistent URIs for UK legislation from the outset. There are a number of different ways one might assign an unequivocal identifier to a legislative document. We have decided to use HTTP URIs and see no particular advantage in using URNs over HTTP URIs and indeed some disadvantages with URNs. Most importantly, HTTP URIs are actionable names. The advantage is that there is a built-in, ready-made, widely deployed and cost-effective resolution mechanism for resolving the identifier to a document, and a document to a representation. Having said that, we would consider supporting URN:LEX URNs in addition to our own URI Set, and would greatly welcome feedback from the community on this issue -– so please do comment if you have a view.

So, it follows, there are three types of URI for legislation on legislation.gov.uk, namely, identifier URIs, document URIs and representation URIs. Identifier URIs are for the ‘concept’ of a piece of legislation, how it was, how it is, and how it will be. (See, e.g., here.) Our use of these follow the Linked Data principles — the identifier URI is for a so-called non-information resource, something which can’t be conveyed in an electronic message. In other words, the URI is for the notion of a piece of legislation, rather than a particular rendition of it in a document. These URIs have been designed following the guidelines the UK Government has created for URI Sets, which our work helped to shape.

With legislation.gov.uk we support content negotiation, and follow the HTTP-Range 14 resolution approach, of responding to a request for the ‘non-information resource’ URI with a 303 response which redirects to a document URI.

Our document URIs refer to particular documents on the Web, for example the current, in-force version of a particular section of an Act. (See, e.g., here.) Crucially there are also point-in-time URIs for documents, which shows how that Act stood on a particular date (/yyyy-mm-dd) (see, e.g., here), or how it was when originally made (/enacted) (see, e.g., here). For any document we can return different representations or formats: a Web page on legislation.gov.uk, the underlying XML, a PDF, an HTML snippet, or even some RDF metadata. We recommend that people cite UK legislation in HTML by pointing to the identifier URI and by using the rel=”cite” attribute in the anchor tag.

Of course, we quickly discovered, it is one thing to suggest a design approach like PRESTO, and quite another to actually implement it. Jeni Tennison, who, working as a consultant to The Stationery Office, devised the URI Set for legislation (and much else about the legislation.gov.uk system), has blogged about the limitations of PRESTO and XPath-based URLs. I hope Jeni will find the time to blog some more about legislation.gov.uk, as there are many stories to be told.

One of the earliest pieces of design work we did for legislation.gov.uk was the URI Set. We wanted to follow PRESTO principles, but also account for changes over time, and for some of the peculiarities of UK legislation, in particular different geographic extents. (See, e.g., here.) PRESTO thinking is very evident on legislation.gov.uk; just look at the URLs as you move through the site.

Linked Data

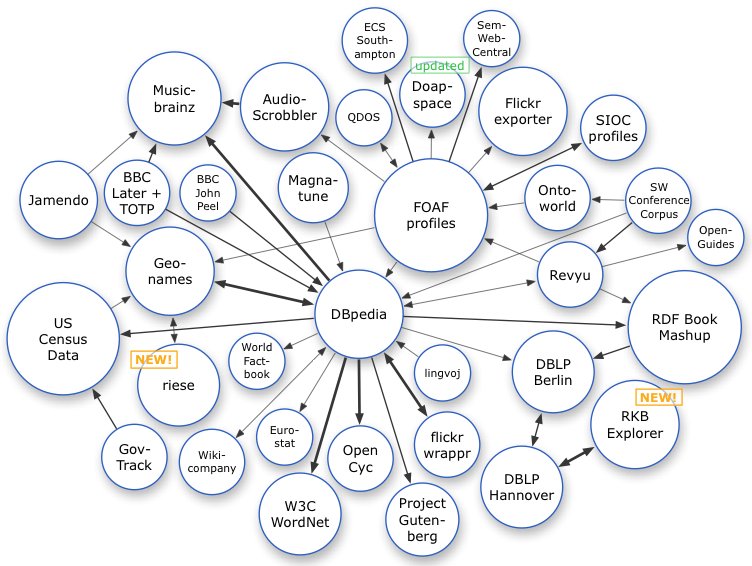

We were also keen that the UK’s Statute Book make a contribution to the growing Web of Linked Data. The UK government is working hard to publish government data using Linked Data standards as part of work on data.gov.uk. The idea of the Web of Linked Data is to connect related information across the Web based on its meaning. In practice this means creating names for things (by ‘thing’ I mean anything: people, places, ideas) using HTTP, and when someone requests some information about that thing, returning data about it, ideally using RDF.

We were also keen that the UK’s Statute Book make a contribution to the growing Web of Linked Data. The UK government is working hard to publish government data using Linked Data standards as part of work on data.gov.uk. The idea of the Web of Linked Data is to connect related information across the Web based on its meaning. In practice this means creating names for things (by ‘thing’ I mean anything: people, places, ideas) using HTTP, and when someone requests some information about that thing, returning data about it, ideally using RDF.

Legislation can make an important contribution to the Web of Linked Data. First, many important concepts and ideas are formally defined by statute. For example, there are 27 types of school in the UK and each one has a statutory definition. (See, e.g., here and here.) What it means to be a private limited company is again defined by statute, as are the UK’s eight data protection principles. One of our objectives with legislation.gov.uk is to enable people creating vocabularies and ontologies to exploit these definitions. This can be done, for example, by using the skos:definition property, to link terms in a vocabulary to the statute. The idea is to ease the process of rooting the Semantic Web in legally defined concepts. Part of the value of this linking is that it enables automatic checking to determine whether a part of the statute book has been repealed, in which case the related concept no longer exists. Crucially, legislation.gov.uk gives accurate information about when a section is repealed, by what piece of legislation, and when that repeal comes into force.

At the moment, the RDF from legislation.gov.uk is limited to largely bibliographic information. We have made use of the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) and the MetaLex vocabularies, primarily to relate the different types of resource we are making available. FRBR has the notion of a work, expressions of that work, manifestations of those expressions, and items. Similarly, MetaLex has the concepts of a BibliographicWork and BibliographicExpression. In the context of legislation.gov.uk, the identifier URIs relate to the work. Different versions of the legislation (current, original, different points in time, or prospective) relate to different expressions. The different formats (HTML, HTML Snippets, XML, and PDF) relate to the different manifestations. We have also made extensive use of Dublin Core Terms, for example to reflect that different versions apply to geographic extents. This is important as, for example, the same section of a statute may have been amended in one way as it applies in Scotland and in another way for England and Wales. We think FRBR, MetaLex, and Dublin Core Terms have all worked well, individually and in combination, for relating the different types of resource that we are making available.

One challenge we have is with changes to legislation that have yet to be applied to the data by the editorial team. Since we know what these effects are, we have also tried to represent this in RDF. We have used the MetaLex vocabulary to do this, but the result is complicated to interpret, and thus we suspect difficult for users of the data. MetaLex does not aid the elegant expression of amendment information (such as: statute A is changed by statute B, but only when commencement order C brings that change into force). We will be developing our own light-weight ontology for expressing some of these relationships, with the primary focus on ease of querying our data, rather than creating an ontology with the expressive power to be a cross-jurisdictional model.

It should then be possible to align this ontology with others post hoc. Our current use of RDF — and the potential to do more — is another issue where we would welcome feedback from the community.

Early adopters

People have already started to make use of the legislation.gov.uk URIs to support their Linked Data. One example is a project by ESD Toolkit. They have a created a SKOS vocabulary for all the different types of service that Local Authorities need to provide. They have linked this vocabulary to the powers and duties placed on Local Authorities in the legislation, using legislation.gov.uk identifier URIs. They have also used the API to pull back some of the text of the relevant statutes.

The future

We think there is huge potential over the next few years in the development of “accountable systems”. These are systems that are explicitly aware of statutory and other legal requirements and are able to process information explicitly in a way that complies with the (ever-changing) law. Here the legislation URIs can help enormously, either for people seeking to develop such accountable systems or any time someone wants to integrate an external system with the official source for statutory information. If the API is used in this way, we will need to consider carefully whether, and if so, how, the data is authenticated. We are not currently supplying digitally signed versions of UK legislation (unlike the GPO in the US) but we will be supporting the use of HTTPS, to provide a reasonable level of secure access to the data. However, if the data starts to be increasingly used in a new generation of accountable systems, we may need to address authenticity, with a view to increasing the guarantees we can make over the data.

There is much more we can do with legislation as data. Parts of the statute book are surprisingly well structured. For example, every year there is one or more Appropriation Acts. These typically contain a schedule with a table listing each government department, the amount allocated to it by Parliament for the year, and what that departments’ objectives are (see, e.g., here). It wouldn’t take much to create an XSLT just for these tables in the Appropriation Acts, from the XML provided from the API, to extract this data from all the Appropriation Acts, and publish that as Linked Data. There are many other examples of almost-structured data in legislation, waiting to be freed by developers, now that they have easy access to the underlying source.

We see this as a start. There is still much to do if we are to realise the potential of the statute book as public source of data. We are aiming to improve the modelling and the quantity of RDF data we make available about legislation, but it’s what others will do with the data that is really interesting. Now the UK has opened its statute book as Linked Data, we are keen to share our work with other governments, and to engage with academics in the legal informatics community and others with an interest in exploiting this rich source of information.

John Sheridan is Head of e-Services and Strategy at The [UK] National Archives, where he leads the team responsible for legislation.gov.uk. He is a specialist in official publishing on the Web, and in using Linked Data standards for government information. He also co-chairs the W3C eGovernment Interest Group.

John Sheridan is Head of e-Services and Strategy at The [UK] National Archives, where he leads the team responsible for legislation.gov.uk. He is a specialist in official publishing on the Web, and in using Linked Data standards for government information. He also co-chairs the W3C eGovernment Interest Group.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor in chief is Robert Richards.