[Editor’s Note: We are pleased to publish this piece from Qiang Lu and Jack Conrad, both of whom worked with Thomson Reuters R&D on the WestlawNext research team. Jack Conrad continues to work with Thomson Reuters, though currently on loan to the Catalyst Lab at Thomson Reuters Global Resources in Switzerland. Qiang Lu is now based at Kore Federal in the Washington, D.C. area. We read with interest their 2012 paper from the International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development (KEOD), “Bringing order to legal documents: An issue-based recommendation system via cluster association”, and are grateful that they have agreed to offer some system-specific context for their work in this area. Their current contribution represents a practical description of the advances that have been made between the initial and current versions of Westlaw, and what differentiates a contemporary legal search engine from its predecessors. -sd]

In her blog on “Pushing the Envelope: Innovation in Legal Search” (2009) [1], Edinburgh Informatics Ph.D. candidate K. Tamsin Maxwell presents her perspective of the state of legal search at the time. The variations of legal information retrieval (IR) that she reviews − everything from natural language search (e.g., vector space models, Bayesian inference net models, and language models) to NLP and term weighting − refer to techniques that are now 10, 15, even 20 years old. She also refers to the release of the first natural language legal search engine by West back in 1993−WIN (Westlaw Is Natural) [2]. Adding to this on-going conversation about legal search, we would like to check back in, a full 20 years after the release of that first natural language legal search engine. The objective we hope to achieve in this posting is to provide a useful overview of state-of-the-art legal search today.

What Maxwell’s article could not have predicted, even five years ago, are some of the chief factors that distinguish state-of-the-art search engines today from their earlier counterparts. One of the most notable distinctions is that unlike their predecessors, contemporary search engines, including today’s state-of-the-art legal search engine, WestlawNext , separate the function of document retrieval from document ranking. Whereas the first retrieval function primarily addresses recall, ensuring that all potentially relevant documents are retrieved, the second and ensuing function focuses on the ideal ranking of those results, addressing precision at the highest ranks. By contrast, search engines of the past effectively treated these two search functions as one and the same. So what is the difference? Whereas the document retrieval piece may not be dramatically different from what it was when WIN was first released in 1993, what is dramatically different lies in the evidence that is considered in the ranking piece, which allows potentially dozens of weighted features to be taken into account and tracked as part of the optimal ranking process.

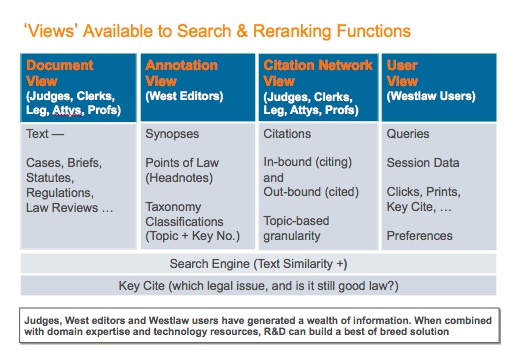

Figure 1. The set of evidence (views) that can be used by modern legal search engines.

In traditional search, the principal evidence considered was the main text of the document in question. In the case of traditional legal search, those documents would be cases, briefs, statutes, regulations, law reviews and other forms of primary and secondary (a.k.a. analytical) legal publications. This textual set of evidence can be termed the document view of the world. In the case of legal search engines like Westlaw, there also exists the ability to exploit expert-generated annotations or metadata. These annotations come in the form of attorney-editor generated synopses, points of law (a.k.a. headnotes), and attorney-classifier assigned topical classifications that rely on a legal taxonomy such as West’s Key Number System [3]. The set of evidence based on such metadata can be termed the annotation view. Furthermore, in a manner loosely analogous to today’s World Wide Web and the lattice of inter-referencing documents that reside there, today’s legal search can also exploit the multiplicity of both out-bound (cited) sources and in-bound (citing) sources with respect to a document in question, and, frequently, the granularity of these citations is not merely at a document-level but at the sub-document or topic level. Such a set of evidence can be termed the citation network view. More sophisticated engines can examine not only the popularity of a given cited or citing document based on the citation frequency, but also the polarity and scope of the arguments they wager as well.

In addition to the “views” described thus far, a modern search engine can also harness what has come to be known as aggregated user behavior. While individual users and their individual behavior are not considered, in instances where there is sufficient accumulated evidence, the search function can consider document popularity thanks to a user view. That is to say, in addition to a document being returned in a result set for a certain kind of query, the search provider can also tabulate how often a given document was opened for viewing, how often it was printed, or how often it was checked for its legal validity (e.g., through citator services such as KeyCite [4]). (See Figure 1) This form of marshaling and weighting of evidence only scratches the surface, for one can also track evidence between two documents within the same research session, e.g., noting that when one highly relevant document appears in result sets for a given query-type, another document typically appears in the same result sets. In summary, such a user view represents a rich and powerful additional means of leveraging document relevance as indicated through professional user interactions with legal corpora such as those mentioned above.

It is also worth noting that today’s search engines may factor in a user’s preferences, for example, by knowing what jurisdiction a particular attorney-user practices in, and what kinds of sources that user has historically preferred, over time and across numerous result sets.

what jurisdiction a particular attorney-user practices in, and what kinds of sources that user has historically preferred, over time and across numerous result sets.

While the materials or data relied upon in the document view and citation network view are authored by judges, law clerks, legislators, attorneys and law professors, the summary data present in the annotation view is produced by attorney-editors. By contrast, the aggregated user behavior data represented in the user view is produced by the professional researchers who interact with the retrieval system. The result of this rich and diverse set of views is that the power and effectiveness of a modern legal search engine comes not only from its underlying technology but also from the collective intelligence of all of the domain expertise represented in the generation of its data (documents) and metadata (citations, annotations, popularity and interaction information). Thus, the legal search engine offered by WestlawNext (WLN) represents an optimal blend of advanced artificial intelligence techniques and human expertise [5].

Given this wealth of diverse material representing various forms of relevance information and tractable connections between queries and documents, the ranking function executed by modern legal search engines can be optimized through a series of training rounds that “teach” the machine what forms of evidence make the greatest contribution for certain types of queries and available documents, along with their associated content and metadata. In other words, the re-ranking portion of the machine learns how to weigh the “features” representing this evidence in a manner that will produce the best (i.e., highest precision) ranking of the documents retrieved.

Nevertheless, a search engine is still highly influenced by the user queries it has to process, and for some legal research questions, an independent set of documents grouped by legal issue would be a tremendous complementary resource for the legal researcher, one at least as effective as trying to assemble the set of relevant documents through a sequence of individual queries. For this reason, WLN offers in parallel a complement to search entitled “Related Materials” which in essence is a document recommendation mechanism. These materials are clustered around the primary, secondary and sometimes tertiary legal issues in the case under consideration.

Legal documents are complex and multi-topical in nature. By detecting the top-level legal issues underlying the original document and delivering recommended documents grouped according to these issues, a modern legal search engine can provide a more effective research experience to a user when providing such comprehensive coverage [6,7]. Illustrations of some of the approaches to generating such related material are discussed below.

Take, for example, an attorney who is running a set of queries that seeks to identify a group of relevant documents involving “attractive nuisance” for a party that witnessed a child nearly drowned in a swimming pool. After a number of attempts using several different key terms in her queries, the attorney selects the “Related Materials” option that subsequently provides access to the spectrum of “attractive nuisance”-related documents. Such sets of issue-based documents can represent a mother lode of relevant materials. In this instance, pursuing this navigational path rather than a query-based one turns out to be a good choice. Indeed, the query-based approach could take time and would lead to a gradually evolving set of relevant documents. By contrast, harnessing the cluster of documents produced for “attractive nuisance” may turn out to be the most efficient approach to total recall and the desired degree of relevance.

To further illustrate the benefit of a modern legal search engine, we will conclude our discussion with an instructive search using WestlawNext, and its subsequent exploration by way of this recommendation resource available through “Related Materials.”

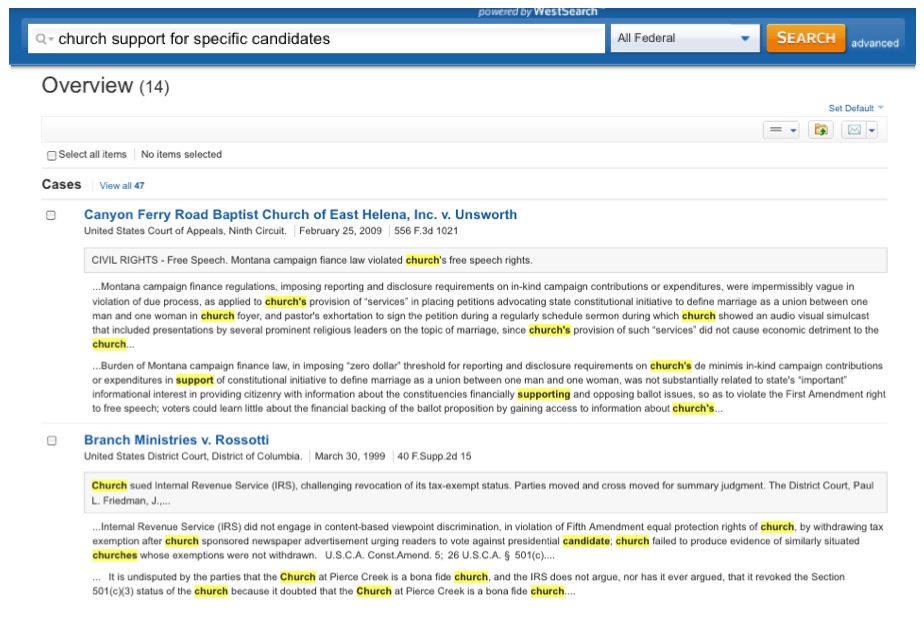

The underlying legal issue in this example is “church support for specific candidates”, and a corresponding query is issued in the search box. Figure 2 provides an illustration of the top cases retrieved.

Figure 2: Search result from WestlawNext

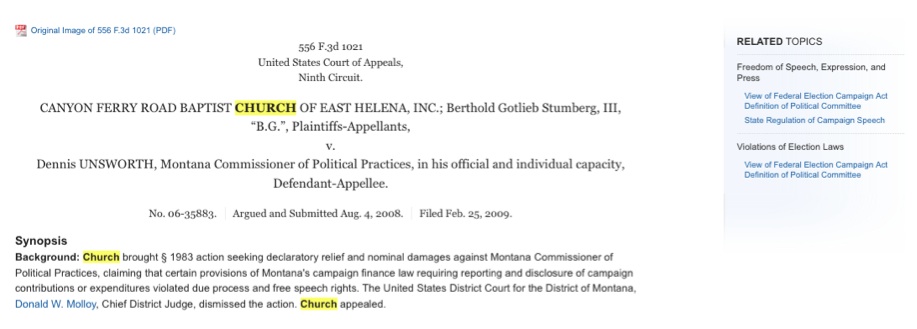

Let’s assume that the user decides to closely examine the first case. By clicking the link to the document, the content of the case is rendered, as in Figure 3. Note that on the right-hand side of the panel, the major legal issues of the case “Canyon Ferry Road Baptist Church … v. Unsworth” have been automatically identified and presented with hierarchically structured labels, such as “Freedom of Speech / State Regulation of Campaign Speech” and “Freedom of Speech / View of Federal Election Campaign Act / Definition of Political Committee,” … By presenting these closely related topics, a user is empowered with the ability to dive deep into the relevant cases and other relevant documents without explicitly crafting any additional or refined queries.

Figure 3: A view of a case and complementary materials from WestlawNext

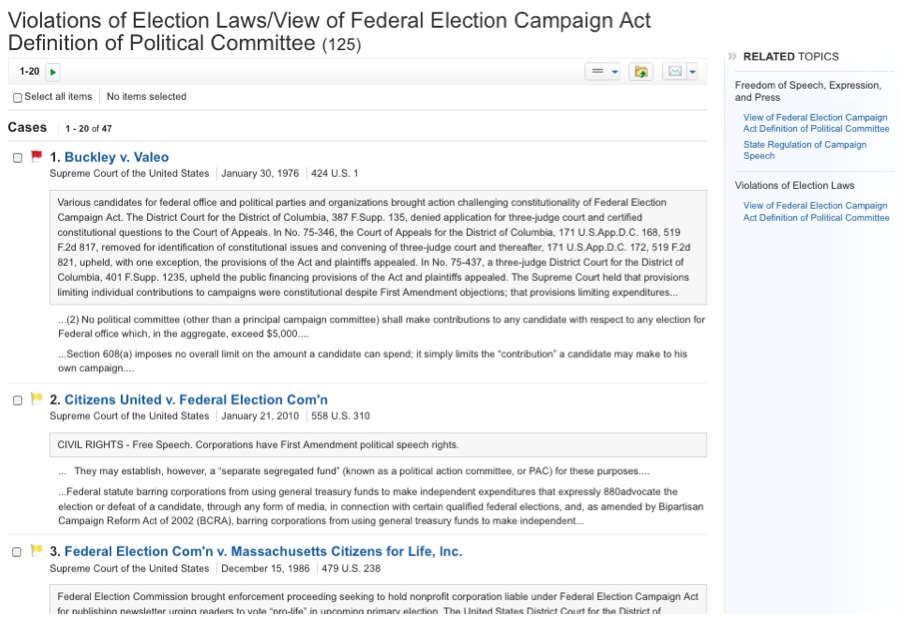

By selecting these sets of relevant topics, a set of recommended cases will be rendered under that particular label. Figure 4, for example, shows the related topic view of the case under the label of “Freedom of Speech / View of Federal Election Campaign Act / Definition of Political Committee.” Note that this process can be repeated based on the particular needs of a user, starting with a document in the original results set.

Figure 4: Related Topic view of a case

In summary, by utilizing the combination of human expert-generated resources and sophisticated machine-learning algorithms, modern legal search engines bring the legal research experience to an unprecedented and powerful new level. For those seeking the next generation in legal search, it’s no longer on the horizon. It’s already here.

References

[1] K. Tamsin Maxwell, “Pushing the Envelope: Innovation in Legal Search,” in VoxPopuLII, Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School, 17 Sept. 2009. http://blog.law.cornell.edu/voxpop/2009/09/17/pushing-the-envelope-innovation-in-legal-search/

[2] Howard Turtle, “Natural Language vs. Boolean Query Evaluation: A Comparison of Retrieval Performance,” In Proceedings of the 17th Annual International ACM-SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR 1994) (Dublin, Ireland), Springer-Verlag, London, pp. 212-220, 1994.

[3] West’s Key Number System: http://info.legalsolutions.thomsonreuters.com/pdf/wln2/L-374484.pdf

[4] West’s KeyCite Citator Service: http://info.legalsolutions.thomsonreuters.com/pdf/wln2/L-356347.pdf

[5] Peter Jackson and Khalid Al-Kofahi, “Human Expertise and Artificial Intelligence in Legal Search,” in Structuring of Legal Semantics, A. Geist, C. R. Brunschwig, F. Lachmayer, G. Schefbeck Eds., Festschrift ed. for Erich Schweighofer, Editions Weblaw, Bern, pp. 417-427, 2011.

[6] On Cluster definition and population: Qiang Lu, Jack G. Conrad, Khalid Al-Kofahi, William Keenan, “Legal Document Clustering with Build-in Topic Segmentation,” In Proceedings of the 2011 ACM-CIKM Twentieth International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM 2011)(Glasgow, Scotland), ACM Press, pp. 383-392, 2011.

[7] On Cluster association with individual documents: Qiang Lu and Jack G. Conrad, “Bringing order to legal documents: An Issue-based Recommendation System via Cluster Association,” In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development (KEOD 2012) (Barcelona, Spain), SciTePress DL, pp. 76-88, 2012.

Jack G. Conrad currently serves as Lead Research Scientist with the Catalyst Lab at Thomson Reuters Global Resources in Baar, Switzerland. He was formerly a Senior Research Scientist with the Thomson Reuters Corporate Research & Development department. His research areas fall under a broad spectrum of Information Retrieval, Data Mining and NLP topics. Some of these include e-Discovery, document clustering and deduplication for knowledge management systems. Jack has researched and implemented key components for WestlawNext, West‘s next-generation legal search engine, and PeopleMap, a very large scale Public Record aggregation system. Jack completed his graduate studies in Computer Science at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst and in Linguistics at the University of British Columbia–Vancouver.

Qiang Lu was a Senior Research Scientist with Thomson Reuters Corporate Research & Development department. His research interests include data mining, text mining, information retrieval, and machine learning. He has extensive experience of applying various NLP technologies in various data sources, such as news, legal, financial, and law enforcement data. Qiang was a key member of WestlawNext research team. He has a Ph.D. in computer science and engineering from State University of New York at Buffalo. He is now a managing associate at Kore Federal in Washington D.C. area.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.