VoxPopuLII

| Everything is Editorial: Why Algorithms are Hand-Made, Human, and Not Just for Search Anymore | Rough Consensus, Running Standards: The Restatement Project |

It’s hard for me to pin down exactly when I knew I wanted to build a legal research ontology. There was no light bulb moment; or perhaps I should say, there was no anvil falling on my head, Wile E. Coyote style. At the beginning of the fall 2012 semester, our Westlaw representative presented the newest features of Westlaw Next, including the new look of the headnotes in case law results. My first glance at it was jarring. At first I thought it was just the font and the streamlined interface, but after taking a closer look at it, I realized it was also the content.

The outline of the headnotes had been compressed. It was substantively different. Previously, each section of the key number system in your headnote was presented in outline form with indented lines and roman numerals, and you could click on any of the outline headings. In the new version, only the main key number heading and the section pertaining to the case are visible. While there is a Change View link in each case result that leads to the classic outline view, I am sceptical of it for a couple of reasons. One is that Westlaw has made the new look the default look and could at some point do away with the Change View option. Second, the new look becomes the look for each new class of law students. If style is all that is communicated by the interface, it would not be of much concern. But there is substance. There is function. How do we now communicate this substance? Should we be so dependent on vendors in legal research teaching? Given the paucity of time we have with first-year students, do we have other viable options?

These questions were in the back of my mind when I attended the LVI conference at Cornell later that semester. On the first day of the conference, I settled in to the Data Organization and Legal Informatics Track. By the end of the day, two of the presentations I heard, one on concept mapping and another on semantic web technologies using RDF and OWL, opened up a door to a new set of possibilities. One of the notes I scribbled during the conference was “ontology for westlaw problem?” I came back from the conference and began researching ontologies and ontology engineering. (I may have gone a little overboard. At last count, I have over 500 articles and book chapters.)

So what is an ontology exactly? Here’s the definition I’ve cobbled together from my readings and my subsequent translation of those readings into words I can actually understand. (Any conceptual errors are mine.) An ontology is a way to take a set of concepts and organize it in a formalized way (i.e., with standards and naming conventions and a machine-readable structure), using an ontology language that takes advantage of the semantic web. The rest of this blog post will be a more detailed description of this definition.

using an ontology language that takes advantage of the semantic web. The rest of this blog post will be a more detailed description of this definition.

Before you can use the set of concepts to build the ontology, you have to define them. And when I first started thinking about this project, it was on a much grander scale. It didn’t take me long at all to realize that I could not single-handedly create a comprehensive ontology of U.S. law.

I decided to focus on what we do as legal research instructors. I’ve always thought that one of our primary duties is to show our students the big picture so they can be confident in their abilities to research in unfamiliar situations. Our teaching is complicated by the fact that very few of us have the kind of classroom time we would like, and even if we did, we are teaching concepts that students may not put to use for months afterwards. So I wanted this ontology to be something we could use to convey the big picture, as well as a tool our students could use at their point of need.

I further narrowed the focus of the ontology to what we teach 1Ls in basic legal research. We teach them how to research with primary and secondary sources (Type of Research Materials) in the broad categories of law they learn in their IL classes (Area of Law). We teach them about the types of law they will encounter (Type of Law). I also wondered if I could find a way to incorporate all the topics we teach them implicitly. Under the surface of black letter research is the knowledge that our students will be spending their summers as summer associates or summer interns. They will need to produce something tangible for a partner or a senior associate or a judge (Final Product). We’re not sending them out to do research as an intellectual exercise. Not only is something tangible expected from them, but they will also need to keep in mind that their work stems from some type of legal action (Legal Action). That legal action might be a breach of contract headed for litigation, or it might be the need to draft a contract between two parties, i.e., it could be litigation or a transaction.

Based on this focus, I had five classes: Type of Research Materials; Area of Law; Type of Law; Final Product; and Legal Action. I was fortunate enough to be able to participate in the Sixth Conference on Legal Information: Scholarship and Teaching (known as “The Boulder Conference”) with a working paper on the ontology. Drawing from his work on legal research instruction, Paul Callister suggested I add another class, Type of Research Problem. I took his advice, and I am grateful to him for his generosity. And now the classes number six.

My next task was coming up with the terms for the ontology — filling it in, so to speak. Some of the terms were almost self-evident. Types of Law include case law and statutory law and regulations. Areas of Law include torts and civil procedure and property and contracts. For others, the First Decennial Digest is out of copyright and so those terms can be used. Most volumes are available digitally from either HathiTrust or LLMC. (The rest are on a shelf in my office.) Some of the terms are outdated, but most legal concepts change gradually over time. I am also grateful to Ed Walters for sharing Fastcase search results with me (completely stripped of any identifying user data and also deduped). Between these two sources, I haven’t yet run out of terms.

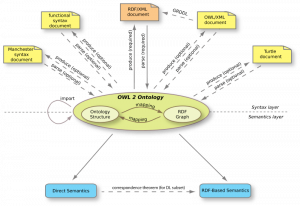

Selecting the ontology language was the easiest part of the endeavor. I learned about the Ontology Web Language (OWL) at the LII conference. In my readings, I had also run across the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), and their standards for OWL (now in two versions, OWL 1 and OWL 2). If you really want to let your inner geek out for a romp, go there and happy fun times will be had.

I also needed a program to build the ontology using the W3C standards and naming conventions. Protege is a free and open-source software program developed and distributed by Stanford University. It comes with extensive user guides. It allows for the creation, sharing and publishing of ontologies, and it uses OWL. And fortunately, a voluminous amount has been written and presented on the topic of ontology engineering, from papers and book chapters to slide decks on sites like SlideShare.

At this point, I am in the beginning stages of taking advantage of all the semantic web has to offer. The ontology’s classes now have subclasses. I am building the relationships between the classes and subclasses, and using Protege to bring them all together. I am also prototyping lesson plans that can take advantage of the ontology. For example, if you write a problem for your students that requires them to research strict tort liability for failure to warn of the danger in the use of a product, you can also use the ontology to bring in the Restatement Third of Torts: Products Liability, as well as secondary sources such as treatises. You can also tie this into whatever final product you want your students to produce: a client letter; a memo to the firm; results of research into punitive damages awards, etc. As long as you have the ontology classes set up, you can add anything to them in order to personalize your research problem.

I also hope to host the ontology on a website with a section for instructors to share lesson plans and ontology files. The files from Protege use an .owl extension, so they can be shared as easily as a pdf. All you need is a program like Protege to open the file. You could use the file as-is or modify it for any type of legal research problem. I also hope that the complete ontology, consisting of the permutations of legal research, can be available for students to query when they are researching as associates and interns.

Amy Taylor is the Access Services Librarian and Adjunct Professor at American University Washington College of Law. Her main research interests are legal ontologies, organization of legal information and the influence of online legal research on the development of precedent. You can reach her on Twitter @taylor_amy or email: amytaylor@wcl.american.edu.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.

3 Responses to “Building a Legal Research Ontology”

Leave a Reply

Recent Posts

- The Balancing Act: Looking Backward, Looking Ahead

- 25 for 25: So What(‘s Next)?

- You with the law show?

- 25 for 25: City Miles, Jazz, and Beacons

- Deeply intertwingled laws

- 25 for 25: A Librarian’s Free Law Awakening

- A birthday message

- 25 for 25 – Documents to Data : A Legal Memex

- 25 for 25: Envisioning Free Access to Caselaw

- The debate on research quality criteria for legal scholarship’s assessment: some key questions

[…] Taylor, JD, MLIS, of American University, has posted Building a Legal Research Ontology, at […]

I let my “inner geek” out and read your article and found it to be fascinatingly ambitious. Please keep us posted with developments and examples of the development of the ontology.

Paul

Thanks so much, Paul! I’ll definitely keep you posted.