Over the past couple of years, there has been a great deal of discussion — particularly in relation to the Durham Statement [1] — about technical standards and preservation issues for law reviews that publish openly and exclusively online. Other colleagues have already blogged or written more formally about the lack of metadata being produced in the production of law reviews, and about problems in indexing open access law journal literature. [2] In a previous VoxPopuLII post, Dr. Núria Casellas discussed the significance of semantic enhancement and how it affects how we should be thinking about providing access to legal information. [3] So I would like to marry the two discussions, by formally asking my academic law librarian colleagues whether the time has come for us to work together to develop an ontology [4], a substantive knowledge system that could be used by our law schools’ legal journals in “marking up” content for consumption on the Internet.

Over the past couple of years, there has been a great deal of discussion — particularly in relation to the Durham Statement [1] — about technical standards and preservation issues for law reviews that publish openly and exclusively online. Other colleagues have already blogged or written more formally about the lack of metadata being produced in the production of law reviews, and about problems in indexing open access law journal literature. [2] In a previous VoxPopuLII post, Dr. Núria Casellas discussed the significance of semantic enhancement and how it affects how we should be thinking about providing access to legal information. [3] So I would like to marry the two discussions, by formally asking my academic law librarian colleagues whether the time has come for us to work together to develop an ontology [4], a substantive knowledge system that could be used by our law schools’ legal journals in “marking up” content for consumption on the Internet.

This ontology should be applied not only to what we think of as traditional law journal content, but also to “related” content — such as companion blogs, video, data, etc. This related content will inevitably grow, as what we think of as a “journal” evolves. Indeed, a typical “journal” will most likely look very different years from now than it does today. As members of the institutions that publish one of the major forms of literature in law, and as members of organizations that possess significant legal metadata and subject expertise, law librarians are uniquely positioned to facilitate the discoverability and utility of law reviews published on the Web. Such a project also has the potential to support additional projects such as new metrics and ways in which to look at scholarship.

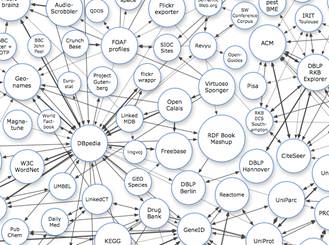

If this system were indeed widely adopted, it could facilitate a type of access to law journal content that has not been accomplished with existing, centralized means of access, such as Google Scholar, the ABA’s project, and commercial databases. Ideally, I would like to see our community develop a cooperative that could provide a hosted technical infrastructure to be used by institutions that lack the financial or technical resources to invest in a major repository service or open source solutions. While this idea seems “utopian” at this point, I think that our community could realistically pursue standards and language for the more “substantive” aspects of the metadata, even if we are unable to agree on the ultimate solutions for preservation or platforms that “serve up” the content. Such an ontology could also serve as a precursor to even more ambitious, collaborative projects to make legal information more accessible and discoverable.

What do you mean by an ontology? Don’t you just mean a taxonomy or “shared vocabulary”?

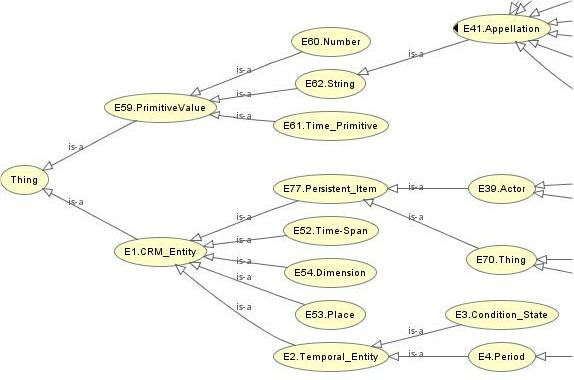

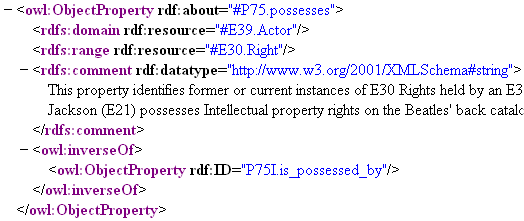

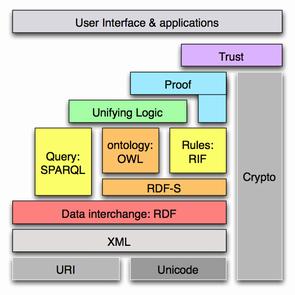

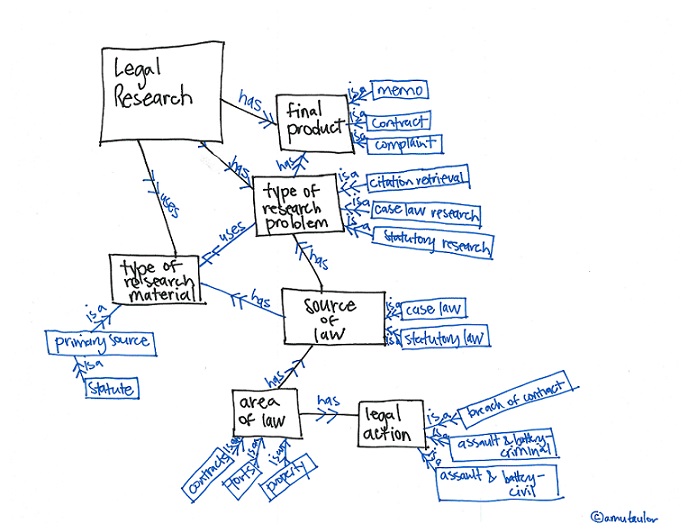

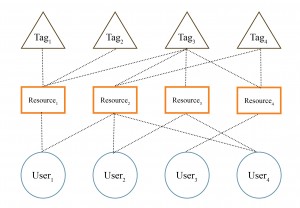

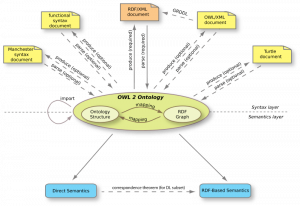

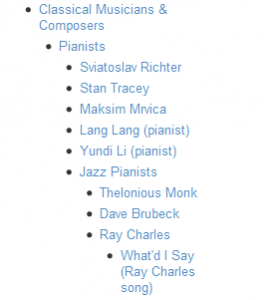

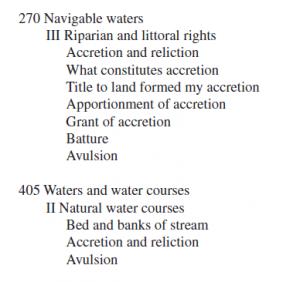

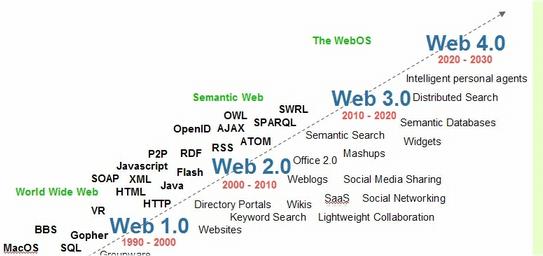

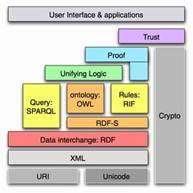

I frame the idea as an “ontology project” because publishing on the Web has increasingly become about structured, open, Linked Data and marking up content for the Semantic Web [4]. As the significance of Linked Data grows, it is important for us to think about access to legal scholarship in terms of knowledge systems that contemplate access to information in those terms. The use of structured data/schemas in publishing law reviews would be optimized by human knowledge/expertise for the expression of ideas and language to be applied in that data. We need to think about subject access beyond the standard, familiar hierarchical “subjects” that we have come to use in our existing taxonomies, indexing, and classification systems. [5] We should be thinking about these “subjects” in a way that shows deeper interrelationships between concepts and “types” and that “interacts” and is “interoperable” with other systems. The ontology approach contemplates access to information from a variety of perspectives in relational and situational ways.

Law reviews could be published in a way that incorporates a particular ontology that could also be mapped to other ontologies. Linking ontologies in this way would yield useful connections across systems, bodies of knowledge, and perspectives, including multilingual thesauri, interdisciplinary knowledge, and practice-oriented and “pro se” consumer perspectives. Thinking about the project as an “ontology” also brings to mind three other important features of the system: (1) the “philosophical” definition of the term “ontology”; (2) the significance of “language” and subject expertise; and (3) the flexibility that would allow us to build something dynamic and responsive to the ever-changing nature of law. Such an approach contemplates the approach to legal information advocated in Dr. Casellas’s piece. [6]

Don’t legal indexes already do this? Why reinvent the wheel?

When some of these issues were raised last October at the workshop entitled “Implementing the Durham Statement: Best Practices for Open Access Law Journals”, someone asked why we should “reinvent the wheel” when other longstanding systems (e.g., law journal indexes) are already doing this. Most of these longstanding systems are based on paid subscription models and are not open in a way that facilitates rapid response to evolving developments in the law, or use by those who consume legal information. More importantly, this project would really be about facilitating publishing and improving access to online content by providing a quality, substantive, open knowledge structure for journals to use for marking up content and building access into publication. This project would not be an attempt to displace or “usurp” indexes which focus on access to content from the “outside” perspective of the publication itself (and which are increasingly concerned with marketable enhancements like full-text access, search features, user interface, Web 2.0 functionality, etc.).

The “wheels” we might be accused of reinventing also include “federated searching” and Web-scale discovery systems being purchased by libraries, but I think similar arguments about cost, perspective on the content, and scope would still apply. Development of our project and adoption of Web-scale discovery systems are not mutually exclusive. Web-scale discovery systems could potentially integrate and map to our system. In any event, the point is not to “throw out“ existing systems, but to create an additional knowledge structure that is open and potentially informed by and interoperable with other existing systems.

How would we proceed?

There are many approaches to ontology development [7], including derivation from or text-mining of legal texts [8], top-down development by humans, and building upon or extracting from existing ontologies. [9] Any of these methods (or a combination thereof) could work in the case of developing an ontological structure that could be applied to law review content.

A “top–down” approach based on the knowledge of individuals could start with librarians. But it should also involve working with law school faculty and scholars having expertise in particular subject areas, as well as with authors of law journal articles, and editors of law journals themselves (particularly those focusing on specialized legal topics). [10] Each law school has faculty and librarians who possess specialized legal subject knowledge — as well as collections in particular areas of law — that could enrich the project. In addition to contributing their substantive knowledge, librarians would have an opportunity to develop a language and a system that reflect how they think about and look for information.

Other colleagues have already suggested greater engagement with law school faculty, for purposes of learning about how faculty conduct and think about research. [11] A project like this would give us the opportunity to engage our stakeholders respecting how they think about, contextualize, and relate topics. (Perhaps we could learn more about the way law library stakeholders think about information by presenting them with samplings of articles, and inquiring as to how the stakeholders would “expect” to find those articles.) Instead of forcing those knowledgeable about their field to learn the taxonomy and structure we have been given by traditional systems, we would be harvesting the expertise of those subject specialists in order to create richer metadata that contemplates their habits and knowledge. Faculty, authors, and journal editors with subject expertise coupled with law librarians could potentially provide a very sophisticated, dynamic, and responsive system.

We should also consider looking at existing ontologies and other systems, including Library of Congress and other popular and relevant systems used in law. There are several ontologies related to law that could inform the project and that could also potentially be mapped. [12] Systems to be consulted (and mapped) could include ontologies designed for primary law and local knowledge management in legal settings, as well as ontologies in subject areas outside the law. Also, some law schools might have their own local systems that could inform ours.

Finally, while we would probably want to avoid using text mining as the only method, the project should also contemplate doing some mining and extraction from law journal literature itself. Such an approach might be particularly helpful in grappling with older legal concepts and appreciating the use of certain terms/language over time.

Whatever method(s) we select, we have a host of inspiration from other projects in legal informatics and from projects in other disciplines (particularly in the sciences) that strive to provide naming conventions within disciplines, and map knowledge across systems through coordinated efforts. Although it is a much more ambitious project than ours, John Willbanks’ Neurocommons project provides us with a model of how such a project could garner participation and grow, particularly if we were to coordinate with other projects and ontologies being developed. [13]

If we build it, who will use it?

If we do develop such a system, who would actually apply it in publishing law reviews? Hopefully, libraries will take the lead and realize that this is a role that they themselves should be fulfilling. While many libraries facilitate repositories and other platforms for publishing law journals and provide training and reference/research support for cite checking and preemption, many do not provide markup and metadata work on the articles themselves. In a recent survey by Benjamin Keele and me in relation to a paper we have been writing, only 1 in 57 respondents reported doing any work on article metadata for their journals. [14] Librarians are already cataloging books and spending time grappling with metadata development and changes in the ways in which we describe our cataloged resources (RDA, FRBR, etc.). Further, librarians today spend a lot of time and money purchasing or building “repositories” or other platforms for their law journals. Greater support of metadata development for our own institutional output (beyond provision of simplistic taxonomies) is a natural outgrowth of such activities. As other librarians have commented, providing institutional repositories is not sufficient. [15]

Such activity could contemplate new roles for catalogers. A recent NISO Webinar on the impact of Linked Data on library cataloging suggested that library catalogers will be less focused on creating “records” and more concerned with “graphs”. The presenters commented that catalogers will enhance the increasing amount of minimal metadata coming directly from publishers, and provide access to original and local content. [16] Some libraries have already integrated metadata work into their workflows for cataloged resources, and it is possible for a law library to integrate journal work into its technical services workflow. [17] From a reference perspective, librarians are already often exposed to journal content in the early stages of publication through support of preemption checking, student note/comment research help, and cite checking support. Librarians are thereby in a good position to understand the “aboutness” of the content. Such involvement could provide law librarians with a natural progression toward being more involved in helping journals “mark up” their content. It is an opportunity for us embrace more wholeheartedly the role of law libraries as publishers and knowledge managers. Many of our colleagues in the open law movement, in knowledge management in legal practice, and in other disciplines have made forays into this area. [18]

Some would probably argue that libraries do not have sufficient staff to get involved in law journal publishing activities, particularly in markup. In addition, some institutions have entire offices outside the library that support publication activities. Even if libraries feel that they are not in a position to manage the workflow of the application of this knowledge system, the most important contribution librarians can make lies in expertise or intellectual input. Application of this ontology could also be performed by law students themselves or other law school staff. Further, authors themselves are potential users and providers of metadata. In many other disciplines, especially the sciences, more authors are using author add-in tools and other software programs to help mark up their manuscripts for publication. Specialized tools could be developed to facilitate authors’ adding metadata to their own law review articles. (Many law authors are already used to contributing keywords to SSRN papers.)

“But…”: Obstacles and opportunities

As I write this piece, I anticipate comments such as, “That would be too big of an undertaking,” and: “Is that really our role?” While libraries are feeling the pressure of more limited resources and time, I would argue that this project would synergize with libraries’ existing interactions with our primary users (faculty and students) and could be built into other outreach activities. In the end, it could actually help to create an organic system responsive to users’ needs. Pursuing this project in tandem with other coordinated activities to facilitate open access law journals, law librarians would join many of our university library colleagues in thinking of ourselves in the role of producer/publisher and in providing new opportunities for our library staff (both technical services and reference/subject specialists).

I envision a host of other issues and problems (too many to enumerate in this posting) that might arise in relation to a project such as this, but I consider none of them “insurmountable.” Below is a sample of some issues that come to mind:

Coordination/governance: Who would control the project? Who would be the final arbiter of what is adopted? Past discussions of the Durham Statement have suggested the possibility of an organization providing support for journals that tried to “comply” with the Durham Statement. [19] Such an organization might consider taking on a project such as this. Perhaps leadership for this project could evolve in some way out of institutional and personal relationships, such as those that have evolved for collection development, [20] or possibly through some coordinated efforts of American Association of Law Libraries (AALL) Special Interest Sections (particularly ALL-SIS, TS-SIS, and RIPS-SIS). If our own institutions are not willing to support such a project, individual librarians on their own (myself included!) might be willing to contribute time and energy to the project. We are also fortunate to have a supportive community of technologists in the open law and knowledge management fields, who could serve as potential partners. The important aspects of the project are that it should be owned by an entity with diverse representation and interests, and that it should be established as something that will be free.

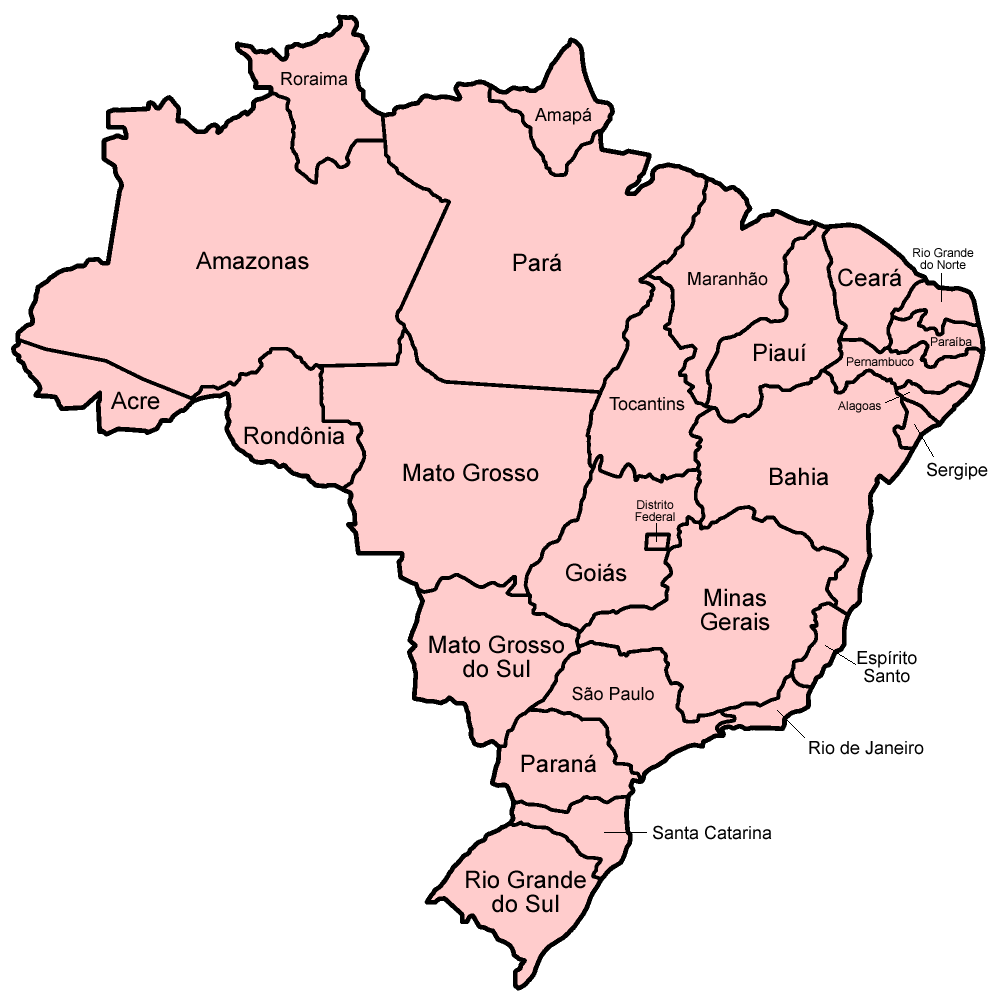

Target content and scope: Would we be framing subjects as they tend to exist in U.S. law review literature? While the structure would be designed for use by law reviews, if it were kept open and without restrictions, it could potentially be adopted by peer-reviewed journals and mapped to other indexing systems, either through Web-scale discovery or other systems. How do we frame an ontology that contemplates incorporation of multiple legal systems and relation to multiple languages? How do we deal with the translation issues that may arise? How would the ontology map to other systems and multilingual thesauri? Should we be contemplating ontologies in other disciplines that have addressed these issues?

Could it be for naught? One might ask, “If we build it, will they come?” Even if provided with such a system (as well as other best practices and support), would law reviews actually adopt it? Even if they do not apply such a system to their data structures, the substantive system that evolves could also be applied from the “outside” by third parties if the content itself is open. While one could argue that this would truly be “reinventing the wheel” in duplicating the efforts of existing indexing systems, one could argue alternatively that the scope, nature, and openness of the resulting system would offer a unique contribution to the indexing environment and would at least provide an additional alternative to the existing systems.

Technical questions: Which particular tools should we use to work collaboratively? What machine-readable formats would we contemplate using? How would we deal technically with systemic changes to the ontology and its application? There is a long list of tools and formats suitable for this project, and of methods for dealing with changes to metadata resources such as ontologies.

How would we contemplate application of this ontology in existing publishing platforms? What tools would we contemplate journals using to mark up documents with metadata from the ontology? Many of the repositories and platforms libraries are currently using permit enhancement of metadata with keywords, user-generated tags, or existing basic subject categories. But existing repositories and platforms do not necessarily facilitate markup that is optimized for the Semantic Web.

Who is the audience? Who is looking for such an ontology? If the language and concepts are at least in part based on the needs and knowledge of our faculty and students, do we develop something tailored to their use instead of developing something that serves broader norms? How could we take into consideration how others (pro se’s, court personnel, etc.) might be looking for information, and map or relate our ontology to other systems that incorporate those users’ perspectives? How could we develop an ontology that contemplates relating to primary law?

Rights issues: Are there rights issues involved in adaptations or derivations of others’ ontologies? How would we want to handle rights issues/licenses respecting the ontology that we develop? [21] Hopefully, the answer is freely and openly!

So what do you think?

Hopefully, this post will spur a discussion that could be continued on this blog or in another forum. In any event, law libraries should be rethinking their roles in the production of law review metadata. Law libraries should be considering how the evolution of the Semantic Web and cataloging standards might impact how they provide support for their own institution’s journals.

NOTES

This post is based in part on two draft papers: Benjamin Keele and Michelle Pearse, How Law Libraries Can Help Law Journals Publish Better (poster session presented during the 2011 AALL Annual Meeting in Philadelphia, PA on July 23-26, 2011), and Michelle Pearse, Whither the Future of Law Journal Indexing?.

[1] Richard A. Danner, Kelly Leong, and Wayne Miller, The Durham Statement Two Years Later: Open Access in the Law School Journal Environment, 103 Law Library Journal 39, 52 (2011), http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/faculty_scholarship/2358/; Implementing the Durham Statement: Best Practices for Open Access Law Journals Conference, http://www.law.duke.edu/libtech/openaccess/conference2010 (October 22, 2010).

[2] Tom Boone, Librarians Key to Open Access Electronic Law Reviews, http://tomboone.com/library-laws/2009/09/librarians-key-open-access-electronic-law-reviews (September 3, 2009) ; Sarah Glassmeyer, Getting to Durham Compliance, SarahGlassmeyer(Dot)Com, http://sarahglassmeyer.com/?p=442 (April 26, 2010); Edward T. Hart, Indexing Open Access Law Journals…or Maybe Not, 38 International Journal of Legal Information 19 (2010), http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli/vol38/iss1/5/.

[3] Dr. Nuria Casellas, Semantic Enhancement of Legal Information: Are We Up for the Challenge?, VoxPopuLII, http://blog.law.cornell.edu/voxpop/2010/02/15/semantic-enhancement-of-legal-information%e2%80%a6-are-we-up-for-the-challenge/ (February 15, 2010).

[4] Some resources related to this topic appear at http://schema.org and http://linkeddata.org. Some argue that the Semantic Web might already be ill-fated: Janna Quitney Anderson and Lee Rainie, The Fate of the Semantic Web, http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2010/PIP-Future-of-the-Internet-Semantic-web.pdf (Pew Research Center 2010). Tom Gruber defines an ontology as “a specification of a conceptualization”: http://www-ksl.stanford.edu/kst/what-is-an-ontology.html; Tom Gruber, in the Encyclopedia of Database Systems, Ling Kiu and M. Tamer Ozsu (Eds.), Spring-Verlag, 2009 http://tomgruber.org/writing/ontology-definition-2007.htm and http://semanticweb.org/wiki/Ontology. Joost Breuker and colleagues elaborate: “The term ‘ontology’ may have different meanings: (i) philosophical discipline; (ii) informal conceptual system; (iii) a formal semantic account; (iv) a specification of a conceptualization; (v) a representation of a conceptual system via logical theory, (vi) the vocabulary used by a logical theory, (vii) a meta-level specification of a logical theory.” J. Breuker et al., “The Flood, the Channels and the Dykes,” in Joost Breuker, Pompeu Casanovas, Michael C.A. Klein and Enrico Francesconi, eds., Law, Ontologies and the Semantic Web: Channeling the Legal Information Flood (IOS Press 2009), at 11. Adam Wyner defines “ontology” in the following way: “An ontology represents a common vocabulary and organization of information that explicitly, formally, and generally specifies a conceptualization of a given domain. Ontologies are related to knowledge management (cf. Rusanow’s ‘Knowledge Management and the Smarter Lawyer’) and taxonomies (cf. Sherwin’s article ‘Legal Taxonomies’). But an ontology is a more specific, explicit and formal representation of knowledge than provided by KM [knowledge management]; and it is richer and more flexible than a taxonomy….In making an ontology, one turns tacit expert knowledge into explicit representations that can be shared, tested and modified by people as well as processed by a computer.” Dr. Adam Z. Wyner, “Legal Concepts Spin a Semantic Web”, Law Technology News, http://www.law.com/jsp/lawtechnologynews10/PubArticleLTN.jsp?id=1202431256007&slreturn=1 (June 8, 2009). Dr. Núria Casellas gives a good explanation of the Semantic Web and ontologies: Dr. Núria Casellas, Semantic Enhancement of Legal Information: Are We Up for the Challenge? http://blog.law.cornell.edu/voxpop/2010/02/15/semantic-enhancement-of-legal-information%e2%80%a6-are-we-up-for-the-challenge/ (February 15, 2010).

[5] Christopher A. Welty and Jessica Jenkins, Formal Ontology for Subject, 31 Journal of Knowledge and Data Engineering 155 (1999) (also available at http://www.cs.vassar.edu/~weltyc/papers/subjects/subject.html); Hope A. Olson, The Power to Name: Locating the Limits of Subject Representation in Libraries (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002); Knowledge Representation with Ontologies: Present Challenges – Future Possibilities, 65 International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 563 (2007), doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2007.04.003.

[6] “In the subfield of computer science and information science known as Knowledge Representation, the term ‘ontology’ refers to a consensual and reusable vocabulary of identified concepts and their relationships regarding some phenomena of the world, which is made explicit in a machine-readable language. Ontologies may be regarded as advanced taxonomical structures, where concepts are formalized as classes and defined with axioms, enriched with description of attributes or constraints, and properties.” Dr. Núria Casellas, Semantic Enhancement of legal Information: Are We Up for the Challenge? http://blog.law.cornell.edu/voxpop/2010/02/15/semantic-enhancement-of-legal-information%e2%80%a6-are-we-up-for-the-challenge/. See also Dr. Adam Z. Wyner, “Legal Concepts Spin a Semantic Web”, Law Technology News, http://www.law.com/jsp/lawtechnologynews10/PubArticleLTN.jsp?id=1202431256007&slreturn=1 (June 8, 2009) (suggesting Web-based collaborative ontology development where legal professionals contribute to a free, open ontology for law); Dr. Adam Z. Wyner, Weaving the Legal Semantic Web with Natural Language Processing, VoxPopuLII, http://blog.law.cornell.edu/voxpop/2010/05/17/weaving-the-legal-semantic-web-with-natural-language-processing/ (May 17, 2010).

[7] Bill Cope, Mary Kalantzis and Liam Magee, Towards a Semantic Web: Connecting Knowledge in Academic Research (Chandos Publishing 2011), at 72 (noting several studies on investigating approaches and software); A Holistic Approach to Collaborative Ontology Development Based on Change Management, 9 Web Semantics: Science, Services and Agents on the World Wide Web 299 (2011), doi:10.1016/j.websem.2011.06.007; “Ontologies can be designed by means of methods such as…encompassing top-down expertise elicitation from humans, bottom-up learning from documents, and middle-out application of design patterns, which can be specialized from domain-independent ontologies, extracted from best practices, existing ontologies or other knowledge sources, as well as learnt from conceptual invariances found in experts’ documents.” Aldo Gangemi, “Introducing Pattern-Based Design for Legal Ontologies,” in Joost Breuker, Pompeu Casanovas, Michel C.A. Klein and Enrico Francesconi, eds., Law, Ontologies and the Semantic Web: Channelling the Information Flood (IOS Press, 2009), at 53.

[8] Enrico Francesconi, Semantic Processing of Legal Texts: Where the Language of Law Meets the Law of Language (Springer 2008).

[9] “Creating and developing ontologies requires domain expertise and the ability to capture this knowledge in a clean conceptual model.” Roberta Cruel, Olga Morozova, Markus Rhode, Elena Simperl, Katharina Siorapes, Oksana Tokarchuk, Torben Wiedenhoefer, and Fahri Yetim, Motivation Mechanisms for Participation in Human-Driven Semantic Content Creation, 1 International Journal of Knowledge Engineering and Data Mining 331 (2011), doi: 10.1504/IJKEDM.2011.040653.

[10] This approach of working with faculty and other scholars from the legal academy would be similar to the “socio-legal” referenced by Dr. Casellas in her post regarding her Institute of Law and Technology project. Dr. Adam Z. Wyner has also advocated web-based collaborative ontolology development where legal professionals contribute to a free, open ontology for law. Dr. Adam Z. Wyner, “Legal Concepts Spin a Semantic Web”, Law Technology News, http://www.law.com/jsp/lawtechnologynews10/PubArticleLTN.jsp?id=1202431256007&slreturn=1 (June 8, 2009).

[11] Stephanie Davidson, Way Beyond Legal Research: Understanding the Research Habits of Legal Scholars, 102 Law Library Journal 561 (2010), http://www.aallnet.org/main-menu/Publications/llj/LLJ-Archives/Vol-102/publljv102n04/2010-32.pdf; Richard A. Danner, Supporting Scholarship: Thoughts on the Role of the Academic Librarian, 39 Journal of Law & Education 365-386 (2010), http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/faculty_scholarship/2071/ .

[12] Robert Richards, Legal Information Systems & Legal Informatics Resources: Knowledge Representation: Legal (Selected) http://www.personal.psu.edu/rcr5122/Ontologies.html; Robert Richards, Legal Information Systems & Legal Informatics Resources: General Resources for Application to Law, http://www.personal.psu.edu/rcr5122/OntologiesGeneral.html; Joost Breuker, Pompeu Casanovas, Michael C.A. Klein, and Enrico Francesconi, eds., Law, Ontologies and the Semantic Web: Channeling the Legal Information Flood (IOS Press 2009), at 12 (table of 23 ontologies).

[13] Alan Ruttenberg et al., Life Sciences on the Semantic Web: The Neurocommons and Beyond. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 10(2): 193-204 (2009), doi: 10.1093/bib/bbp004 (“The NeuroCommons project seeks to make all scientific research materials – research articles, knowledge bases, research data, physical materials – as available and as usable as they can be. We do this by fostering practices that render information in a form that promotes uniform access by computational agents – sometimes called ‘interoperability’. We want knowledge sources to combine easily and meaningfully, enabling semantically precise queries that span multiple information sources.”).

[14] Benjamin Keele and Michelle Pearse, How Law Libraries Can Help Law Journals Publish Better (poster session presented during the 2011 AALL Annual Meeting in Philadelphia, PA on July 23-26, 2011, http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/libpubs/25/).

[15] Tom Boone, Librarians Key to Open Access Law Reviews, http://tomboone.com/library-laws/2009/09/librarians-key-open-access-electronic-law-reviews (September 3, 2009).

[16] NISO/DCMI, International Bibliographic Standards, Linked Data and the Impact on Library Cataloging (Webinar), http://www.niso.org/news/events/2011/dcmi/linked (August 24, 2011).

[17] Valeri Craigle, Legal Scholarship in the Digital Domain: A Technical Roadmap for Implementing the Durham Statement, Technical Services Law Librarian, at 1 (December 2010), http://www.library.illinois.edu/archives/e-records/aall/8501591a/news/TSLLdecember2010.pdf.

[18] See Dr. Adam Z. Wyner, “Legal Concepts Spin a Semantic Web,” Law Technology News, http://www.law.com/jsp/lawtechnologynews10/PubArticleLTN.jsp?id=1202431256007&slreturn=1 (June 8, 2009) (suggesting Web-based collaborative ontology development where legal professionals contribute to a free, open ontology for law).

[19] Wayne Miller, A Foundational Proposal for Making the Durham Statement Real, http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/faculty_scholarship/2325/ (suggesting founding an organization “whose mission is to guarantee the ongoing viability and availability of all publications that adhere to the Durham Statement’s call to action, hereinafter called the Durham Statement Foundation.”); Richard A. Danner, Kelly Leong and Wayne Miller, The Durham Statement Two Years Later: Open Access in the Law School Journal Environment, 103 Law Library Journal 39, 52 (2011), http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/faculty_scholarship/2358/ (noting that the Durham Statement “calls for law schools to end print publication in a planned and coordinated effort led by the legal education community”).

[20] Some examples include the Northeast Foreign Law Libraries Cooperative Group and “B2F2” (currently in the process of being the process of being renamed) with Boston area law librarians.

[21] John Wilbanks, “Licensing and Ontologies: Research from Creative Commons,” http://ontolog.cim3.net/file/work/IPR/OOR-IPR-01_IPR-landscape_2010-09-09/licensing-n-ontologies–JohnWilbanks-CC_20100909.pdf (September 9, 2010).

Michelle Pearse is the Research Librarian for Open Access Initiatives and Scholarly Communication at the Harvard Law School Library where she manages implementation of the law school’s open access policy for its faculty, and other projects related to scholarly communication and open access to legal information and scholarship. She is also involved in efforts to archive born-digital content for the collection, and provides research services to faculty and staff.

Michelle Pearse is the Research Librarian for Open Access Initiatives and Scholarly Communication at the Harvard Law School Library where she manages implementation of the law school’s open access policy for its faculty, and other projects related to scholarly communication and open access to legal information and scholarship. She is also involved in efforts to archive born-digital content for the collection, and provides research services to faculty and staff.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor-in-Chief is Robert Richards, to whom queries should be directed. The statements above are not legal advice or legal representation. If you require legal advice, consult a lawyer. Find a lawyer in the Cornell LII Lawyer Directory.

Such ontologies usually include references to the concepts of Norm, Legal Act, and Legal Person, and may contain the formalization of

Such ontologies usually include references to the concepts of Norm, Legal Act, and Legal Person, and may contain the formalization of  In this regard, at

In this regard, at  Current research is focused on overcoming these problems through the establishment of gold standards in concept extraction and ontology learning from texts, and the idea of

Current research is focused on overcoming these problems through the establishment of gold standards in concept extraction and ontology learning from texts, and the idea of  and the relationships between legal ontology and legal epistemology, legal knowledge and common sense or world knowledge, expert and layperson’s knowledge, legal information and Linked Data possibilities, and legal dogmatics and political science (e.g., in

and the relationships between legal ontology and legal epistemology, legal knowledge and common sense or world knowledge, expert and layperson’s knowledge, legal information and Linked Data possibilities, and legal dogmatics and political science (e.g., in