§.1.- Foreword

«If folksonomies work for pictures (Flickr), books (Goodreads), questions and answers (Quora), basically everything else (Delicious), why shouldn’t they work for law?» (Serena Manzoli)

In a post on this blog, Serena Manzoli distinguishes three uses of taxonomies in law: (1) for research of legal documents, (2) in teaching to law students, and (3) for its practical application.

In regard to her first point, she notes that (observation #1) to increase the availability of legal resources is compelling change of the whole information architecture, and – correctly, in my opinion – she exposes some objections to the heuristic efficiency of folksonomies: (objection #1) they are too “flat” to constitute something useful for legal research and (objection #2) it is likely that non-expert users could “pollute” the set of tags. Notwithstanding these issues, she states (prediction #1) that folksonomies could be helpful with non-legal users.

On the second point, she notes (observation #2) that folksonomies could be beneficial to study the law, because they could allow one to penetrate easier into its conceptual frameworks; she also formulates the hypothesis (prediction #2) that this teaching method could shape a more flexible mindset in students.

In discussing the third point, she notes (observation #3) that different taxonomies entail different ways of apply the law, and (prediction #3) she formulates the hypothesis that, in a distant perspective in which folksonomies would replace taxonomies, the result would be a whole new way to apply the law.

I appreciated Manzoli’s post and accepted with pleasure the invitation of Christine Kirchberger – to whom I am grateful – to share my views with the readers of this prestigious blog. Hereinafter I intend to focus on the theoretical profiles that aroused my curiosity. My position is partly different from that of Serena Manzoli.

§.2.- Introduction

In order to detect the issues stemming from folksonomies, I think it is relevant to give some preliminary clarifications.

In collective tagging systems, by tagging we can describe the content of an object – an image, a song or a document – label it using any lexical expression preceded by the “hashtag” (the symbol “#”) and share it with our friends and followers or also recommend it to an audience of strangers.

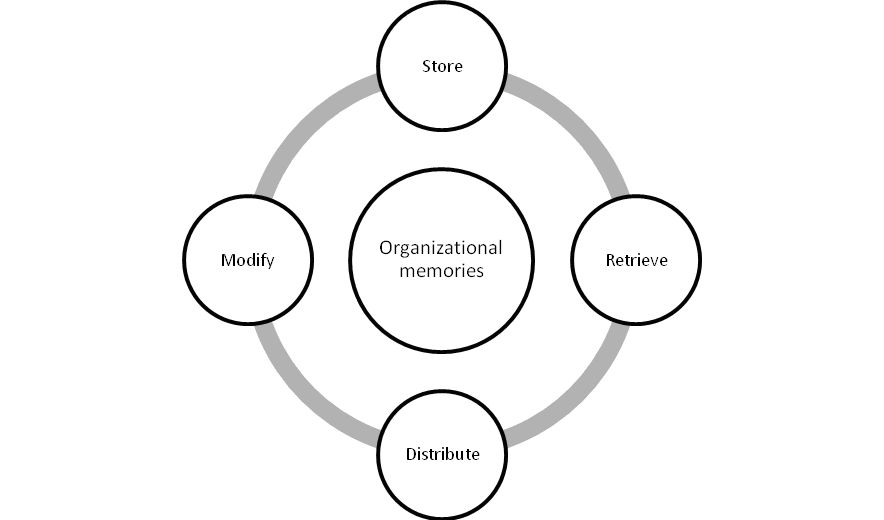

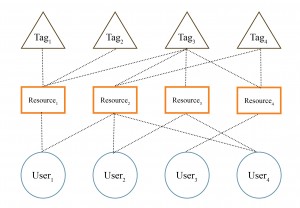

Folksonomies (blend of the words “taxonomy” and “folk”) are sets of categories resulting from the use of tags in the description of on line resources by the users, allowing a “many to many” connection between tags, users and resources.

Thomas Vander Wal coined the word a decade ago – ten years is really a long time in ICTs – and these technologies, as reported by Serena Manzoli, have now been adopted in most of the social networks and e-commerce systems.

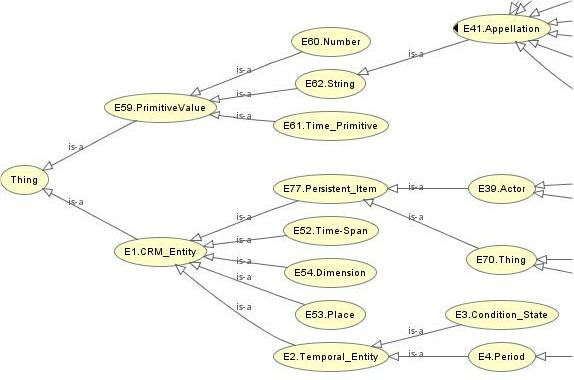

The main feature of folksonomies is that tags aggregate spontaneously in a semantic core; therefore, they are often associated with taxonomies or ontologies, although in these latter cases hierarchies and categories are established before the collection of data, as “a priori”.

Simplifying, I can say that tags may describe three aspects of the resources, using particulars (i.e. a picture of a flowerpot lit by the sun):

(1) The content of the resources (i.e. #flowers),

(2) The interaction with other specific resources and the environment in general (i.e. #sun or #summer),

(3) The effect that these resources have on users having access to them (i.e. #beautiful).

Since it seems to me that none of these aspects should be disregarded in an overall assessment of folksonomies, I will consider all of them.

Having regard to law, they end to match with these three major issues:

(1) Law as a “content”. Users select legal documents among others available and choose those that seem most relevant. As a real interest is – normally – the driving criterion of the search, and as this typically is given by the need to solve a legal problem, I designate this profile with the expression «Quid juris?».

(2) Law as a “concept”. This problem emerges because the single legal document can not be conceived separately from the context in which it appears, namely the relations it has with the legal system to which it belongs. Consequently becomes inevitable to ask what the law is, as a common feature of all legal documents. Recalling Immanuel Kant in the “Metaphysics of Morals”, here I use the expression «Quid jus?».

(3) Law as a “sentiment”. What emerges in folksonomies is a subjective attitude that regards the meaning to be attributed to the research of resources and that affects the way in which it is performed. To this I intend to refer using the expression «Cur jus?».

§.3.- Folksonomies, Law, and «Quid juris?»: legal information management and collective tagging systems

In this respect, I agree definitely with Serena Manzoli. Folksonomies seem to open very interesting perspectives in the field of legal information management; we admit, however, that these technologies still have some limitations. For instance: just because the resources are tagged freely, it is difficult to use them to build taxonomies or ontologies; inexperienced users classify resources less efficiently than the other, diluting all the efforts of more skilled users and “polluting” well-established catalogs; vice versa, even experienced users can make mistakes in the allocation of tags, worsening the quality of information being shared.

Though in some cases these issues can be solved in several ways – i.e., the use of tags can be guided with the tag’s recommendation, hence the distinction between broad and narrow folksonomies – and even if it can reasonably be expected that these tools will work even better in the future, for now we can say that folksonomies are useful just to integrate pre-existing classifications.

I may add, as an example, that an Italian law requires the creation of “user-created taxonomies (folksonomies),” “Guidelines for websites of public administrations” of 29 July 2011, page 20. These guidelines have been issued pursuant to art. 4 of Directive 26th November 2009 n. 8, of the “Minister for Public Administration and Innovation”, according to the Legislative Decree of 7 March 2005, n. 82, “Digital Administration Code” (O.J. n. 112 of 16th May 2005, S.O. n. 93). It may be interesting to point out that in Italian law the innovation in administrative bodies is promoted by a specific institution, the Agency for Digital Italy (“Agenzia per l’Italia Digitale”), which coordinates the actions in this field and sets standards for usability and accessibility. Folksonomies indeed fall into this latter category.

Following this path, a municipality (Turin) has recently set up a system of “social bookmarking” for the benefit of citizens called TaggaTO.

§.4.- Folksonomies, Law, and «Quid jus?»: the difference between the “map” and the “territory”

In this regard, my theoretical approach is different from that of Serena Manzoli. Here is the reason our findings are opposite.

Human beings are “tagging animals”, since labelling things is a natural habit. We can note it in common life: each of us, indeed, organizes his environment at home (we have jars with “salt” or “pepper” written on the caps) and at work (we use folders with “invoices” or “bank account” printed on the cover). The significance of tags is obvious if we consider using it with other people: it allows us to establish and share a common information framework. For the same reasons of convenience, tags have been included in most of the software applications we use (documents, e-mail, calendars) and, as said above, in many online services. To sum up, labels help us to build a representation of reality: they are tools for our knowledge.

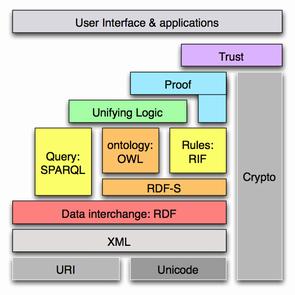

In regard to reality and knowledge, it may be recalled that in the twentieth century there were two philosophical perspectives: the “continental tradition”, focused on the first (reality) and pretty much common in Europe, and the “analytic philosophy”, centered on the second (knowledge and widespread among USA, UK and Scandinavia. More recently, this distinction has lost much of its heuristic value and we have seen rising a different approach, the “philosophy of information”, which proposes, developing some theoretical aspects of cybernetics, a synthesis of reality and knowledge in an unifying vision that originates from a naturalistic notion of “information”.

I will try to simplify, saying that if reality is a kind of “territory”, and if taxonomies (and in general ontologies) can be considered as a sort of representation of knowledge, then they can be considered as “maps”.

In light of these premises, I should explain what to me “sharing resources” and “shared knowledge” mean in folksonomies. Folksonomies are a kind of “map”, indeed, but different than ontologies. In a metaphor: ontologies could be seen as “maps” created by a single geographer overlapping the reliefs of many “territories”, and sold indiscriminately to travelers; folksonomies could be seen as “maps” that inhabitants of different territories help each other to draw by telephone or by texting a message. Both solutions have advantages and disadvantages: the former may be detailed but more difficult to consult, while the latter may be always updated but affected by inaccuracies. In this sense, folksonomies could be said “antifragile” – according to the brilliant metaphor of Nassim Nicholas Taleb – because their value improves with increased use, while ontologies could be seen as “fragile”, because of the linearity of the process of production and distribution.

Therefore, as the “map” is not the “territory”, reality does not change depending on the representation. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the “maps” are not helpful to travel to unknown “territories”, or to reach faster the destination even in “territories” that are well known (just like when driving in the car with the aid of GPS).

On the application of folksonomies to the field of law, I shall say that, after all, legal science has always been a kind of “natural folksonomy”. Indeed, it has always been a widespread knowledge, ready to be practiced, open to discussion, and above all perfectly “antifragile”: new legal issues to be solved determine a further use of the systems, thus causing an increase in knowledge and therefore a greater accuracy in the description of the legal domain. In this regard, Serena Manzoli in her post also mentioned the Corpus Juris Civilis, which for centuries has been crucial in the Western legal culture. Scholars went to Italy from all over Europe to study it, at the beginning by noting few elucidations in the margins of the text (glossatores), then commenting on what they had learned (commentatores), and using their legal competences to decide cases that were submitted to them as judges or to argue in trials as lawyers.

Modern tradition has refused all of this, imposing a rationalistic and rigorous view of law. This approach – “fragile”, continuing with the paradigm of Nassim Nicholas Taleb – has spread in different directions, which simplifying I can lower to three:

(1) Legal imperativism: law as embodied in the words of the sovereign.

(2) Legal realism: law as embodied in the words of the judge.

(3) Legal formalism: law as embodied in administrative procedures.

For too long we have been led to pretending to see only the “map” and to ignore the “territory”. In my opinion, the application of folksonomies to law can be very useful to overcome these prejudices emerging from the traditional legal positivism, and to revisit a concept of law that is a step closer to its origin and its nature. I wrote “a step closer”; I’d like to clarify, to emphasize that the “map”, even if obtained through a participatory process, remains a representation of the “territory”, and to suggest that the vision known as the “philosophy of information” seems an attempt to overlay or replace the two terms – hence its “naturalism” – rather than to draw a “map” as similar as possible to the “territory”.

§.5- Folksonomies, Law and «Cur jus?»: the user in folksonomies: from “anybody” to “somebody”

This profile does not fall within the topics covered in Manzoli’s post, but I would like to take this opportunity to discuss it because it is the most intriguing to me.

Each of us arranges his resources according to the meaning that he intends to give his world. Think of how each of us arrays the resources containing information that he needs in his work: the books on the desk of a scholar, the files on the bench of a lawyer or a judge, the documents in the archive of a company. We place things around us depending on the problem we have to address: we use the surrounding space to help us find the solution.

With folksonomies, in general, we simply do the same in a context in which the concept of “space” is just a matter of abstraction.

What does it mean? We organize things, then we create “information”. Gregory Bateson in a very famous book, Steps to an Ecology of Mind – in which he wrote on “maps” and “territories”, too – stated that “information” is “the difference that makes the difference”. This definition, brilliant in its simplicity, raises the tremendous problem of the meaning of our existence and the freedom of will. This issue can be explained through an example given by a very interesting app called “Somebody”, recently released by the contemporary artist Miranda July.

The app works as follows: a message addressed to a given person is written and transmitted to another, who delivers it verbally. In other words, the actual recipient receives the message from an individual who is unknown to him. The point that fascinates me is this: someone suddenly comes out to tell that you “make a difference,” that you are not “anybody” because you are “somebody” for “somebody.” Moreover, at the same time this same person, since he is addressing you, becomes “somebody,” because the sender of the message chose him among others, since he “meant something” to him.

For me, the meaning of this amazing app can be summed up in this simple equation:

“Being somebody” = “Mean something” = “Make a difference”

This formula means that each of us believes he is worth something (“being somebody”), that his life has a meaning (“mean something”), that his choices or actions can change something – even if slightly – in this world (“make a difference”).

Returning to Bateson, if it is important to each of us to “make a difference”, if we all want to be “somebody”, then how could we settle down for recognize ourselves as just an “organizing agent”? Self-consciousness is related to semantics and to the freedom of choice: who is not free at all, does not create any “difference” in the world. Poetically, Miranda July makes people talk to each other, giving a meaning to humanity and a purpose to freedom: this is what “making a difference” means for humans.

In applying folksonomies to law, we should consider all this. It is true that folksonomies record the way in which each user arrays available legal documents, but it should be emphasized the purpose for which this activity is carried out. Therefore, it should be clear that an efficient cataloguing of resources depends on several conditions: certainly that the user shall know the law and remember its ontologies, but also that he shall be focused on what he is doing. This means that the user needs to be well-motivated, in order to recognize the value of what he is doing, so that to give meaning to his activity.

§.6- Conclusion

I believe that folksonomies can teach us a lot. In them we can find not only an extraordinary technical tool, but also – and most importantly – a reason to overcome the traditional legal positivism – which is “ontological” and therefore “fragile” – and thus rediscover the cooperation not only among experts, but also with non-experts, in the name of an “antifragile” shared legacy of knowledge that is called “law”.

All this will work – or at least, it will work better – if we remember that we are human beings.

I hold a Master’s degree in Law and a Ph.D. in Philosophy of Law from the University of Padua (Italy).

Currently I am Researcher in Philosophy of Law (Legal informatics) in the Department of Legal sciences at the University of Udine (Italy).

My study aims to bridge philosophy, computer science and law, focusing on the strife between human nature and new technologies. Recently I am investigating the theoretical implications of ICTs on «social ontology», the concept of law as an instrument of social control as emerging from the «peer to peer economy», the use of folksonomies in legal information management and the theoretical aspects of Digital evidence.

I teach Legal Informatics in the Faculty of Law of Udine. In my lectures on cyberlaw, which I study since 2000, I bring out the critical profiles of the “Information Society” from the discussion of the most recent jurisprudence.

I am also a Lawyer. I am registered in the Bar Association of Udine (Italy) in a special section (full time academic researchers and professors).

My full profile can be visited on www.linkedin.com .

My complete list of publications can be found on https://air.uniud.it.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.

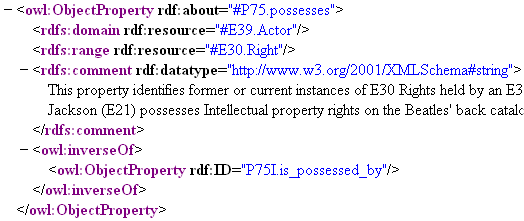

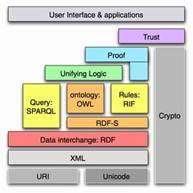

Such ontologies usually include references to the concepts of Norm, Legal Act, and Legal Person, and may contain the formalization of

Such ontologies usually include references to the concepts of Norm, Legal Act, and Legal Person, and may contain the formalization of  In this regard, at

In this regard, at  Current research is focused on overcoming these problems through the establishment of gold standards in concept extraction and ontology learning from texts, and the idea of

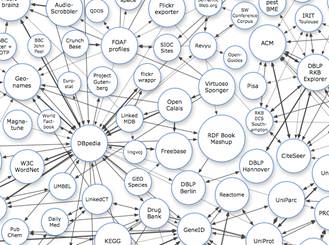

Current research is focused on overcoming these problems through the establishment of gold standards in concept extraction and ontology learning from texts, and the idea of  and the relationships between legal ontology and legal epistemology, legal knowledge and common sense or world knowledge, expert and layperson’s knowledge, legal information and Linked Data possibilities, and legal dogmatics and political science (e.g., in

and the relationships between legal ontology and legal epistemology, legal knowledge and common sense or world knowledge, expert and layperson’s knowledge, legal information and Linked Data possibilities, and legal dogmatics and political science (e.g., in