The legal profession has for long been notoriously averse to change, but now even the legal industry is affected by a new harsher reality with widespread changes impacting legal practice and client service. These changes come not merely from the aftermath of the economic downturn with price pressure and increased demands from clients, but also from the technological developments and regulatory changes that provide breeding ground for new kinds of competition. This post discusses the future of legal service, with a specific focus on how the current changes on the legal market demand a more strategic approach to knowledge management and efficient working processes and how technology is becoming more and more important as a way to develop new innovative ways to deliver legal services.

1. CHANGING LEGAL MARKET

For a long time, the legal market has been spared from some of the general business realities applicable to almost all other industries. Law has been something of a protected industry, with lawyers in a unique position as the only legitimate provider with access to legal knowledge and tools and no real competition – a “black box” exempt from normal rules of business, such as predictability in cost and time, budget restraints and value for money. After selection, the relationship with the client was controlled by the law firm, which decided almost entirely by itself how the service was to be delivered, billing it by the hour and dictating cost, pricing, staffing and strategic direction, with no need to innovate or provide cost-efficient legal services. Jordan Furlong has described this closed market more in detail and how the legal marketplace now is changing, in the series “The evolution of the legal services market stage 1-5”

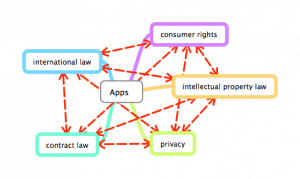

But now, there are strong drivers for change affecting the legal market and rapidly forcing it out of the “black box” towards a new reality. One such driver is the regulatory changes in UK, with the Legal Services Act allowing different types of lawyer and non-lawyer to form businesses together, thereby facilitating the development of Alternative Business Structures, with external investments, in legal service providers. These regulatory changes have opened up the legal market for a new kind of competition from new entrants with disruptive business models. Unlike conventional law firms, these new providers tend to have a greater focus on rethinking legal services. They have developed both different kinds of legal services and new ways of providing them. They use technology to improve the way they connect to clients, offering new and easier ways to conduct legal tasks over the Internet, providing cloud-based customized legal documents and advice with arguments like “No surprise pricing. No hourly fees, no shocking bills.” This is a market that has gained a large interest from venture capitalists, for example by Google Venture in Rocket Lawyer (which recently also acquired competitor Law Pivot), Kleiner Perkins and Institutional Venture Partners in LegalZoom and Quotidian Ventures and others in Docracy. All this clearly indicates that there is a large market opportunity for these kinds of new legal solutions that are efficient, technology-driven and affordable to users. Other interesting new legal service or knowledge providers are VentureDocs, Docstoc and the Swedish Moretime Growth On Demand. Soon, we will probably also see global legal service providers outside the legal sphere, such as department stores or investment banks, accounting firms, insurance companies, or even Amazon.

Law firms also face a new kind of competition from Legal Process Outsourcing providers (LPOs), where legal work is exported to an outside law firm or legal support services company, often in low-wage markets overseas such as India, but also to new providers within the same country or to new brands established by the law firm itself, such as Herbert Smith’s document review centre in Belfast. The most commonly offered services are document review and legal research, but recently LPOs have started to move up the value chain by providing not only due diligence services but also the agreement drafting in M&A transactions. As reported in “LPOs Stealing Deal Work from Law Firms” alternative legal service providers are beginning to take the bread-and-butter of large law firms – handling whole mergers and acquisitions, not just the due diligence aspects of deals. Beyond cost savings, LPO has advantages like access to outside talent, 24-7 availability, and the ability to quickly scale up or cut back operations. According to the international LPO Market Study, general counsel are increasingly bypassing law firms and instructing legal process outsourcing suppliers directly. Currently worth over $1bn (£629m), the LPO market is forecast to double in size in the next two to three years.

A third major driver for change is the new client demands. Due to budget restraints, most general counsel face what Professor Richard Susskind refers to as the “more for less-challenge”, when clients have more legal issues to handle, but less in-house resources and less budget to spend on external advisers. This challenge has forced general counsel to examine alternative solutions, demand discounts and alternative fee arrangements, ask for predictability and metrics–all demands for added value and efficiency. When law firms are no longer the only providers in the legal market, clients have a diverse set of options to choose from for legal advice and they no longer accept hourly billing for inefficient work. General counsel are more closely reviewing external advisers and are very cost driven. More and more they turn to cost-effective solutions, like LPOs, or deploy the idea of “multi-sourcing” with the use of different legal service providers on different elements of a legal matter. Basically, the client has taken over the driver’s seat from law firms and is now dictating cost, pricing, staffing and strategic direction, which previously was in the law firm’s control. Together, these two factors — a decline in overall legal spending and new options for legal services — combine to reduce demand for the services of lawyers.

Susan Hackett, in her key note presentation at VQ Forum 2012, described current legal market developments, which are based on shrinking demand and increasing supply, competition from non-legal sources, and a lack of experience to guide us in this rapidly changing reality. Today, many law firms still continue to work as if they can charge whatever they want for the limited services they wish to provide, which makes it difficult to profit from the more efficient and effective service delivery demanded in this competitive marketplace, while delivering greater client value. Most law firm base the lawyer compensation on lawyer activity instead of on client results. Many law firms do not even ask for feedback but simply assume that they are doing well and don’t need to change: “While 85% of partners think clients love them, only 35% of clients recommend their existing outside counsel to other clients.”

To address this “disconnect” between the lawyers’ high perception of their value, and re-connect it to what clients actually want their lawyers to do is essential in order to improve the value of long-term client relationships. Susan Hackett also pointed to the decreased client loyalty. The 2012 Altman Weil Chief Legal Officer Survey makes it clear that clients are on the move without concern for loyalty. The study reports that 77% of the participants terminate their relationships with at least one firm last year, while only 17% give their law firms an “A” grade and 87% rate their law firms’ efficiency as “low.”

An interesting new initiative to pinpoint law firms’ inefficiency has been made by D. Casey Flaherty, who has developed a basic technology competency audit that he administers to his outside counsel to show how the lack of proficiency with the common software tools at their disposal (Word, Excel, Acrobat, etc.) result in an inordinate amount of time wasted that is still billed to clients.

The fourth major driver for change on the legal market is the collaboration trend. Today’s business conditions has completely changed with the so-called ”sharing economy” and the new generation of ”Millenials”, as defined by inter alia futurist Michael Rogers. Michael Rogers talks about the future of the legal industry as an era inspired by the Millenials; those who do not consider themselves limited to meeting people in their neighborhood but instead create relationships with people all around the world, based on interests instead of locality. In this era, new business is gained through referrals and by creating relationships through social technologies, collaboration and providing information for free. This ”freemium” trend has also been noted for legal professionals in the American Bar Association’s Legal Technology Survey Report, where 56% of the respondents use a free online source for their legal research.

Clients are becoming more and more aware of the collaboration advantage. There are more and more legal collaboration portals available, such as the Association of Corporate Counsel that provides templates and other legal documents to its members, and Legal OnRamp, a collaboration system for in-house counsel and invited outside lawyers and third party service providers. Another interesting collaboration example is Pfizer Legal Alliance, a collaboration program for Pfizer’s outside counsel, which makes them work more closely and collaboratively both with Pfizer and with each other using standardized fixed-fee billing arrangements. Richard Susskind also talks about the “collaboration strategy” for law firms, where clients can come together and share the costs of certain types of legal service, as well as collaboration projects between law firms and clients, by online closed communities for collaboration, online legal services, automated drafting and electronic legal marketplaces. Although some lawyers might find this controversial, such collaboration has already started to take place: six major banks and the law firm Allen & Overyhave created a joint online legal risk management tool.

2. NEW STRATEGIC APPROACH TO KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND EFFICIENT WORKING PROCESSES

Analysing what is happening on the legal market with the new trends with LPOs, new legal service providers, virtual law firms and the increased collaboration and knowledge sharing within legal networks, you can see that clients are becoming more and more aware of new tools and processes and will start demanding their lawyers to adapt to the new technology to become more efficient. Law firms, therefore, have to review the value of their services and the use of technology to streamline processes and take better advantage of a firm’s accumulated knowledge to ensure better service than their competitors.

For the first time in legal history, there is now a true incentive for law firms to deliver results faster, through the right combination of internal and external resources and the better use of IT as a competitive edge.

This means that law firms have to take a new strategic approach to knowledge management as a business development tool, a way of delivering the changes and innovation that will help law firms to survive and thrive in today’s dynamic and uncertain business and professional landscape.

Furthermore, clients are no longer depending upon their law firms to receive standardized legal documents, since there are several sites with online legal documents easily available, often for free, as well as collaboration portals. Law firms have lost control over the legal documents they earlier considered the “crown jewels” of the firm. It also means that demanding and skilled clients, like in-house counsels, have easy access to more affordable legal resources and are becoming less willing to pay high fees for some of the work done by junior associates.

Law firms, therefore, have to rethink their view of these legal documents and realize they are only the basis for their legal service and are already easy available for the clients. Instead, they have to look closer at how to better share knowledge from their experience, better re-use documents they have developed, standardize more routine work, and to analyse their most valuable knowledge in order to leverage it to fully support their clients.

The American Lawyers’ survey reported recently that law firms seem to have realised this need for a more strategic approach to knowledge management (KM) and that firms were pushing for greater efficiency in their internal operations. Nearly half of the 200 responding law firms said they had aligned partner compensation with a willingness to cooperate in new initiatives, such as knowledge management. Mary Abraham has discussed the impact of this report in “Guiding Partners to Better Law Firm KM” and how KM professionals best should take advantage of this windfall by avoiding the traditional precedent collection projects or model-document drafting projects and instead focus on high-impact KM activities. This means investing in the KM projects that will provide the greatest return on investment for the firm. This also means that legal knowledge management is transforming, from the previously dominating precedent and knowledge-base building, to focus on problem solving and business development. Legal KM today is something very different from legal KM in its early days. Ron Friedmann has provided his inside insights on this transition in “The Evolution of KM from Content to Tools to True Productivity”:

“In the 1990s, we talked about work product retrieval and precedents. That continued into the new century until we finally realised how hard it is to find work products and to write, maintain, and organize precedents. Moreover, we also realised that content is not enough. We broadened our focus to finding experienced lawyers and finding relevant matters. /…/ More recently, KM has shifted again. Many KM professionals today focus on legal project management, alternative pricing arrangements and process improvement. In my view, this reflects more a discontinuity or abrupt shift than evolution. Legal KM sees the light: content is not an end. Even software is only a means to an end. The real end, the real goal, perhaps the Holy Grail, is improving lawyer productivity; is solving real problem.”

Michael Koenig also points to how “legal KM has its roots in helping attorneys practice more efficiently and effectively, by drawing on colleagues’ prior work product and through sharing information, expertise, and documents within the firm. Historically, much of this sharing happened without colleagues realizing it—KM was at work behind the scenes finding and organizing resources created by individual attorneys and providing searchable, efficient access to that product to all attorneys.” But when “combining strategic development of template or master resources with document automation, KM can shift attorneys from the ancient practice of search/save as/edit to web-based questionnaires that generate a customized “best practice” final document, at a fraction of the time and cost it would take to start from scratch and without the propensity for errors inherent in editing an older document.”

What is really interesting today is that not only legal KM professionals sees this “Holy Grail of legal KM” that Ron Friedmann refers to, but also recent developments in the legal publishing world prove that legal publishers are on the same path; e.g. Rocket Lawyers acquisition of LawPivot and Thomson Reuters’ launch of client-centric platforms. Thus both legal KM professionals and legal publishers seem to agree that it is not enough to provide information, work products or precedents. Instead, focus is on supporting lawyers to improve the way they work and serve clients, and ultimately to improve how law firms operate as businesses.

In “Is KM a Real Force Multiplier?” Mary Abraham explained how KM needs to improve productivity and problem solving and how “the key to force multiplications is not to settle for incremental improvements but to aim for dramatically improved results”. With such a new focus, the Holy Grail of legal knowledge management appears to be within reach — where the goal of KM is to provide true competitive advantage by developing a combination of tools and content to improve lawyer productivity, solve real problems and make the business more profitable.

By using IT in the right way, the possibilities of finding relevant information will be substantially improved and the internal knowledge sharing will be leveraged, since previous lessons learned, best practices and new ways of solving problems can be better shared and taken advantage of by all lawyers. Through these methods, substantial efficiency improvements and increased profitability can be reached. Developments in information technology will enhance the efficiency of legal work, not only by the use of standard documents like templates and checklists, but also by proceduralized processes and automated workflows. Systematization can also extend, however, to the actual drafting of documents by the use of document assembly technology. By implementing automated document production to support standardization, firms will be able to deliver the same quality legal services and still maintain profit margins regardless of fee structure.

Richard Susskind predicts this to be the future of legal service: “These systems, which can be used within legal businesses or made available online, are disruptive for lawyers who charge for their time, because they enable documents to be generated in minutes whereas, in the past, they would have taken many hours to craft. The end result is a tailored solution, delivered by an advanced system rather than by a human craftsman. That is the future of legal service.”

3. CONCLUSION

With a new approach to knowledge management as a management issue for the whole business, with embraced technology and new approaches to standardization by using document assembly tools and buying basic documents externally, substantial improvements in efficiency and increased profitability can be reached. Law firms will prosper by finding new legal services to offer their clients. New business opportunities will arise in the provision of services to fixed prices by the use of new specialized and individualized solutions for clients.

Helena Hallgarn and Ann Björk are founders of Virtual Intelligence VQ, a Swedish consultancy firm that combines the practice of law with IT and knowledge management skills. They are two of the most experienced knowledge management professionals in Scandinavia, with backgrounds from legal practice and KM work at Scandinavian law firms Vinge, Mannheimer Swartling and Gernandt & Danielsson. Their focus is to strategically develop legal KM and drive innovation in the legal profession.

Helena and Ann blog at Legal Innovation Blog and manage the LinkedIn-discussion group Legal Innovation. Each year they also arrange VQ Forum with a focus on the most interesting ongoing discussions worldwide on strategy, leadership, innovation, technology and knowledge management for the legal sector. Helena and Ann can also be found as @VQab on Twitter.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.