In the wake of a decisive victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu treated rival Japanese warlords to a simple but effective instrument of control, pioneered in the preceding Era of the Warring States. The Daimyo, as the defeated clan heads were known, retained control of their respective domains, but were required to reside in the newly established seat of government at Edo (now Tokyo) in alternate years. They were free to return home in the off-years, but only by leaving their princesses and heirs behind in the walled gardens of the capitol, as a token of the enduring bond of friendship and mutual admiration that united the Shogun and his sometimes grudging subordinates.

The processions of competing Daimyo moving to and from the seat of real power soon became a measure of status, and the cost of these semi-annual journeys would eventually consume fully half of each Daimyo’s disposable income. This contributed greatly to the prosperity of communities stationed along the wayside, where tradesmen, innkeepers, chefs, entertainers, and the occasional thief shared in revenue extracted from the peasants in the Daimyo’s fiefdom back home. A cynic might say that the practice of san-kin-kōtai (参勤交代) was little more than an elaborate system of hostage-taking, but in its way it was very good for business — at least if you did not have the misfortune to be a peasant.

Japan later shed the hobbles of feudal regulation, of course, and the population are now free to move about as they please; but for Daimyo read content, and for the Daimyo’s princesses and progeny read metadata, and you have a description of a familiar Internet business model. Too familiar, perhaps, as most of us now rely on content supplied through walled gardens for much of our research work.

Just as the freedom of individuals is improved by lifting restraints on travel, so the flow of content is more meaningful when accompanied by the descriptive metadata that is its natural companion. As observed by others in this space (most recently here and here), there are barriers today to the free flow of legal information. As will be outlined below, hamstrung metadata is, unfortunately, one of them. This information — mundane details like the date, court, and party names of a legal decision, and the volume, journal, page or identifier used to locate it — are curiously hard for machines to find in the pages issued by any of the leading commercial services in the 40-year-old online legal information industry.

More than any fundamental difference in the materials themselves, captive metadata accounts for the striking gap that has emerged between the research tools available in law and in other disciplines. Driven by the needs of researchers in the sciences and the humanities, personal research platforms that thrive on metadata are now widely available: to make them servants of the law, they want only to be fed.

One element of this alternative infrastructure that depends on rich metadata provision is the Citation Style Language (CSL), which is the proper subject of this essay. The next three sections provide a short introduction to CSL, followed by a few observations on the state of legal metadata provision on today’s legal Internet. The essay concludes with a comment on some of the lights that seem to be flickering into view at the end of this particular tunnel, and on the prospective benefits of at last bringing the law within reach of a modern research support ecosystem.

About CSL

The Citation Style Language is an XML vocabulary for accurately describing citation and bibliography formats. Given the breath of life by the original Zotero citation formatter, CSL is now entering its eighth year of development, can boast two full production implementations, and drives citation formatting in at least six major bibliographic or text processing projects, with total user numbers in the millions.

The illustration to the right provides a simplified view of CSL processing flow. In greater detail it works like this:

- A running copy of the processor is cast (“instantiated”) using the rules specified in a particular CSL style file.

- The calling application sends fine-grained item metadata to the processor.

- The processor registers data it receives, for the purpose of tracking the document context of each item.

- The calling application sends a request for a citation or a bibliography listing. In the former case, the call will supply information about document state (note numbers and the like), and additional details specific to the request (such as a pinpoint page number).

- The processor analyses the request, calculates any auto-generated item variables, and applies any disambiguation rules defined in the style to assure that item references are unique.

- The processor returns the citation or bibliography listing as a serialized string in the language (such as English or French) and the markup format (such as XHTML or RTF) that it has been configured to deliver.

The upshot of all this swirling machinery is that generic metadata can be used to generate citations in arbitrary formats. In operation, this means that an article originally written according to, say, the Oxford Standard for Citation of Legal Authorities (OSCOLA) can be reformatted on the fly to conform to the requirements of, say, the McGill Guide, or perhaps the Australian Guide to Legal Citation (PDF) or the ALWD Manual. This functionality is used daily by researchers in most fields worldwide, and there is no reason the law should be an exception.

The automated generation of citations is just one benefit of this processing flow; it also enables the embedding of cited metadata directly in the source document (for sharing between collaborators), and it allows links to referenced resources to be attached at the point of production (for ease of referencing after publication). Hints of resistance from some quarters notwithstanding, such tools clearly promise to save law professors, law students, lawyers, court clerks, judges, and others who must do legal drafting a tremendous amount of time.

Formatting citations

There are a few commonly-encountered wrinkles in legal data and citation styles that CSL and the citeproc-js formatter have been carefully designed to address. To give readers a glimpse of this work, a few basic elements of the language are laid out below. We’ll begin with the following sample citation in the OSCOLA style: Jones & others v Wright [1991] 3 All ER 88.

The bare case name can be produced with the following construct:

<text variable="title" font-style="italic" strip-periods="true"/>

(Note the use of font-style=”italic” to render the variable content in italic type, and of the strip-periods=”true” attribute, which will be discussed below.)

The year element can be produced with the following code:

<date variable="issued" form="text" date-parts="year" prefix="[" suffix="]"/>

(Note the use of prefix and suffix.)

To build the full cite, we join these and other elements together by wrapping them in a group element and setting a single space as the delimiter. In the example below, we also define this construct as a macro, so that it can easily be reused in multiple contexts in the style:

<macro name="oscola-case"> <group delimiter=" "> <text variable="title" font-style="italic" strip-periods="true"/> <date variable="issued" form="text" date-parts="year" prefix="[" suffix="]"/> <number variable="issue"/> <text variable="container-title"/> <text variable="page-first"/> </group> </macro>

If we want to use this cite form for English legal cases only, we can wrap it in a condition:

<choose> <if type="legal_case" jurisdiction="gb" match="all"> <text macro="oscola-case"/> </if> </choose>

(Note the type, jurisdiction and match attributes, and the use of a text node with a macro attribute to call our macro.)

With the code above, we will obtain something close to our target cite format if we arrange for the calling application to feed the processor JSON input like the following:

{

"container-title": "All England Law Reports",

"date": {

"date-parts": [["1991"]]

},

"issue": "3",

"page": "88",

"title": "Jones & others v. Wright"

}

Looking carefully at this input, we can see that there are some small discrepancies in the metadata:

- the period after the v; and

- the full name of the reporter.

These details can be handled automatically in the processor. The first issue is trivial: quashing periods is a general requirement of OSCOLA, and this one will be removed by the strip-periods=”true” attribute that we set on the title element. The second issue requires a bit of further explanation.

Applying abbreviations

In our sample input, the journal name has been spelled out in full to avoid ambiguity. This is an example of best practice, although the field content does differ from our desired output of “All ER”. The current version of Zotero provides a journalAbbreviation field for each item, but this has known limitations, and is not suitable for legal writing.

Many styles require that commonly cited journal names, at least, be abbreviated. Some styles have mandatory and idiosyncratic abbreviation requirements. As Judge Posner commented recently (PDF) concerning the requirements of Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation: It’s as if there were a heavy tax on letters, making it costly to write out Coast Guard Court of Criminal Appeals instead of abbreviating it … There is no tax on letters, of course, but the lack of a truly uniform system of abbreviation means that such elaborate schemes impose a significant cost in their own right. In Zotero, if journal abbreviations are registered directly on individual items in the user’s personal library, they must be entered manually for each item, both when the original item is created, and each time the user wants to generate citations in a different style. This is not acceptable: metadata should be generic.

With a view to squaring the needs of users with those of the more demanding styles, the citeproc-js processor allows arbitrary abbreviation lists to be registered and managed on a per-style basis.

Here’s how it works. When the processor encounters a field that requests form=”short”, it looks for the field content in an externally-supplied abbreviation list derived from a small (persistent) database. If there is no match, the processor opens an empty entry for the field in its (ephemeral) run-time registry. In an application that draws on this functionality, the user can visit the run-time listing at any time, and enter suitable abbreviations. These are then registered in the persistent external database, where they are remembered for future use with the current style.

In our case, the user would enter “All ER” as the journal abbreviation, and the application would store and deliver auxiliary input like the following:

{

"container-title": {

"All England Law Reports": "All ER"

}

}

Abbreviations list support has not yet been implemented in mainstream projects, but I have built a small Firefox add-on for use with Zotero that draws upon it, and I am happy to report that it does work, as advertised, both for journal abbreviations, and for other similar purposes (such as “hereinafter” support).

In our CSL code, invoking the abbreviation list machinery requires only a small change to the citation macro:

<macro name="oscola-case">

<group delimiter=" ">

<text variable="title" font-style="italic" strip-periods="true"/>

<date variable="issued" form="text" date-parts="year"

prefix="[" suffix="]"/>

<number variable="issue"/>

<text variable="container-title" form="short"/>

<text variable="page-first"/>

</group>

</macro>

A full style will be more elaborate, but the basic logical structures are the same, with conditional statements used to select simple nested groups of nodes that describe the output to be produced.

I’ll draw a line under the technical discussion at this point, but you get the idea.

I’ll draw a line under the technical discussion at this point, but you get the idea.

CSL is an elegant and expressive language that has grown under the tutelage of strict demands from academics and graduate students in many fields. The language is fully documented in the CSL Specification. The proposed extensions for full legal support, documented in the citeproc-js CSL Specification Supplement, have been carefully formulated, and I am open to feedback. Style development is proceeding apace, and increments and milestones are being reported through the CitationStylist.org website, which serves as a clearinghouse for legal and multilingual style development. From experience with the first target style for full implementation (the Creative Commons licensed OSCOLA), the prospects for CSL style support for legal resources that “disappears”, as such tools ought to do, are very bright.

Input from the Web

In addition to bringing us open-source community-driven citation formatting technology, Zotero offers one-click acquisition of content, to a full-featured personal electronic library on the user’s desktop. This is handy, even essential, in today’s world of overabundant information sources. It is facilitated by the fact that in most fields of study, aggregator sites have a long history of providing access to structured metadata from their pages.

In addition to bringing us open-source community-driven citation formatting technology, Zotero offers one-click acquisition of content, to a full-featured personal electronic library on the user’s desktop. This is handy, even essential, in today’s world of overabundant information sources. It is facilitated by the fact that in most fields of study, aggregator sites have a long history of providing access to structured metadata from their pages.

The server-side technology that enables one-click content acquisition well predates the Internet. Libraries that run their catalogs on the 1980’s MARC standard or one of its variants can and often do expose these records to the Internet. Aggregators in the sciences typically provide BibTeX records, which researchers have relied upon since the original format was frozen in 1988. Booksellers and publishing consortia offer metadata keyed to ISBN numbers, and the publishers of academic and other journals participate in the DOI system for assigning unique IDs keyed to canonical metadata for individual articles. The world of academic discourse is swimming in rich, life-giving metadata. Until, that is, one arrives on the salted shores of the law, where there is no water, and precious little sand.

The metadata story on the paywalled sites is very straightforward: exposing it would not be in the vendor’s commercial interest, so there isn’t any. It’s hard to fault the logic. Even if we insist on the unflattering feudal analogy with which this essay opened, it’s worth remembering that Japan’s Shogunate endured for 250 years before finally giving way to change. Business opportunities don’t come much better than that, and one can hardly expect the leading providers to react any differently.

The metadata story on the paywalled sites is very straightforward: exposing it would not be in the vendor’s commercial interest, so there isn’t any. It’s hard to fault the logic. Even if we insist on the unflattering feudal analogy with which this essay opened, it’s worth remembering that Japan’s Shogunate endured for 250 years before finally giving way to change. Business opportunities don’t come much better than that, and one can hardly expect the leading providers to react any differently.

There is variety in the ecosystem, however, and not all suppliers of legal source are driven by the same pattern of economic incentives. Providers that expose their content with metadata stand to benefit from CSL and other infrastructure-in-waiting, which can significantly raise the real value of their service. To state the point more precisely: supplying fine-grained metadata is essential for a publisher’s content to be attractive to third-party reference management tools like Zotero — it’s important enough to be in the project’s guidance notes.

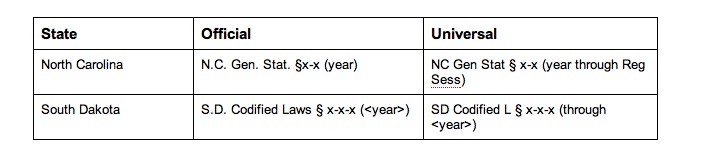

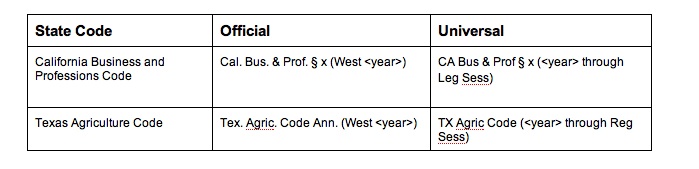

This is a separate point from the movement for universal or format-neutral citation formats. Promotion of these is also important, but from the perspective of data acquisition, they are not sufficiently uniform across jurisdictions to serve, by themselves, as primary metadata for a general research platform. As a well-intended example, consider this tag embedded in a case from CanLII:

<meta name="DC.Title"

content="Smith v. Jones, 2003 CanLII 19166 (NWT RO)"/>

In order to register this item in a reference manager database, we need to know what each of the elements means. This will be obvious to a local practitioner, but a Zotero page translator would need to include hand-crafted pattern-matching functions to parse out the elements and assign them to field variables. If I were doing the coding (ignorant as I am of Canadian law), I would be stumped by several of these elements:

- 19166

- From the size of the number, I guess that it is a document identification number, but if it were smaller, I might mistake it for a page number. That could result in my misclassifying the cite as one to a printed reporter, and that in turn could affect the formatting of pinpoint identifiers in styled output generated from the harvested data.

- NWT

- This appears to be a geographic identifier (Northwest Territories?), but I am not sure. I am also unsure whether such identifiers always appear in citations; whether or not they might include spaces, numbers, or other characters; and what the full set of possible identifiers looks like.

- RO

- This one has me completely stumped, so I would be mailing friends who might know something about Canadian law.

The answers would be obvious to a Canadian lawyer, of course, and with a bit of effort I could look up the details. But multiplied across the jurisdictions of the world, that is an effort that would prove fatal to the task. A meta tag containing a full formatted citation is better than nothing, but with fine-grained metadata and simple descriptive variable names for each of the elements, the code would practically write itself. It really does make all the difference.

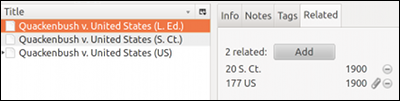

A further issue concerns parallel references, which I mention here for the sake of completeness in ranting. In a world that offers an API to the entire fictional economy of Farmville, one would think that the various and sundry parallel citations to, say, Quackenbush v. US would be available as a simple machine-readable graph. But as we have seen, the leading paywalled providers don’t even supply the date of the decision in structured form, let alone parallel citation mappings: the data they publish is basically useless for this purpose.

The least-painful path at present is to visit Google Scholar with Zotero, and fetch the case from the hit listing (not from the case page itself). This yields a set of three cross-linked items that reflect the parallel reports of the case. One click and you’re away — but consider what happens behind the scenes: (1) the Zotero translator performs contorted screen-scraping of (2) the displayed citations in the Google listing, which (3) were in turn reverse-engineered from scanned source, and hence (4) cannot be trusted for 100% accuracy. It is a testament to human ingenuity that this is possible at all, but the underlying infrastructure is an embarrassing bundle of wet string.

The least-painful path at present is to visit Google Scholar with Zotero, and fetch the case from the hit listing (not from the case page itself). This yields a set of three cross-linked items that reflect the parallel reports of the case. One click and you’re away — but consider what happens behind the scenes: (1) the Zotero translator performs contorted screen-scraping of (2) the displayed citations in the Google listing, which (3) were in turn reverse-engineered from scanned source, and hence (4) cannot be trusted for 100% accuracy. It is a testament to human ingenuity that this is possible at all, but the underlying infrastructure is an embarrassing bundle of wet string.

Parallel references are tracked internally, of course, by the major service providers. Lack of user-side access to these mappings has the side effect (bizarre, from the standpoint of other fields) of placing uncommon importance on human-readable citations, because they are the only available means of identifying a given case across multiple data silos. Given current publishing arrangements, the problem is intractable, and for the present the best we can do on the reference management side is to provide means of recording these relations in personal libraries when they are identified by individual users.

In lieu of concluding

To end on a positive note, compliments are due to the growing number of publishers and dissemination initiatives that have gone the distance to expose well-structured metadata. In the CitationStyles.org project, my own immediate aim is to get the CSL output story into shape, and I confess that I have not followed recent (and some not-so-recent) developments as closely as I should. As styles firm up and field assignment conventions come to be settled, I’ll be looking forward to work (by others, as well as a bit myself) on serving the growing number of open-access legal publishers that provide structured metadata.

To end on a positive note, compliments are due to the growing number of publishers and dissemination initiatives that have gone the distance to expose well-structured metadata. In the CitationStyles.org project, my own immediate aim is to get the CSL output story into shape, and I confess that I have not followed recent (and some not-so-recent) developments as closely as I should. As styles firm up and field assignment conventions come to be settled, I’ll be looking forward to work (by others, as well as a bit myself) on serving the growing number of open-access legal publishers that provide structured metadata.

Zotero is a flexible feeder, and the specific format in which metadata is presented is less important than that it be separated into discrete fields. The meta field assignments in the Cornell LII Supreme Court judgments (CASENAME, DOCKET, DECDATE) serve the purpose. The BibTeX source served by Google Scholar works as well. The legislative metadata at legislation.gov.uk also works. The microformats metadata embedded in Federal cases on law.resource.org gives us enough to work with, and the very complete details in the RECOP material are quite useful when they are carried through in refactored pages (as they are in the Free Law Reporter served by CALI).

One of the benefits to be anticipated, as we make our way toward improved interoperation between publishers and third-party reference management tools for law, is a reduction in the barriers to collaboration between law and other disciplines. Legal citation conventions are by nature quite demanding, and removing some of their sting will improve access not only to the law itself, but also to participation in its discourse.

All signs of rain, and very welcome for grassroots projects like CSL.

Frank Bennett is Associate Professor in the Graduate School of Law at Nagoya University. His active projects related to legal informatics include the citeproc-js CSL processor, an experimental multilingual branch of the Zotero reference manager (MLZ), and the CitationStylist.org initiative for creating a CSL family of legal styles.

Frank Bennett is Associate Professor in the Graduate School of Law at Nagoya University. His active projects related to legal informatics include the citeproc-js CSL processor, an experimental multilingual branch of the Zotero reference manager (MLZ), and the CitationStylist.org initiative for creating a CSL family of legal styles.

The CSL language was originally conceived by Bruce D’Arcus. The CSL 1.0 schema and specification are maintained by Bruce D’Arcus and Rintze Zelle.

(Readers should kindly note that despite Frank’s tasteful choice of hat in the photo to the left, the views expressed in this post are his own, and do not necessarily reflect those of Cornell University or the Cornell Legal Information Institute.)

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor-in-Chief is Robert Richards, to whom queries should be directed. The statements above are not legal advice or legal representation. If you require legal advice, consult a lawyer. Find a lawyer in the Cornell LII Lawyer Directory.

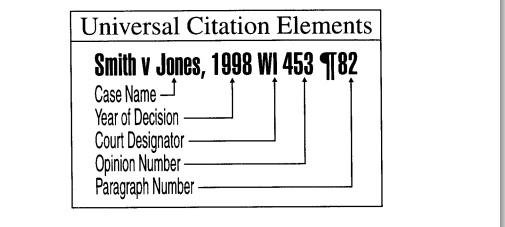

In 2004,

In 2004,  Courts have gradually been adopting the neutral citation, beginning in 1999 and continuing to the present. The first adopter of the neutral citation was the

Courts have gradually been adopting the neutral citation, beginning in 1999 and continuing to the present. The first adopter of the neutral citation was the