Lessons Gained from Parliamentary Information Visualization (PIV)

The emerging topic of Parliamentary Informatics (PI) has opened up new terrain in the research of the scope, usefulness and contribution of Informatics to parliamentary openness and legislative transparency. This is pretty interesting when visualizations are used as the preferred method in order to present and interpret parliamentary activity that seems complicated or incomprehensible to the public. In fact, this is one of the core issues discussed, not only on PI scientific conferences but also on parliamentary fora and meetings.

The issue of Parliamentary Information Visualization (PIV) is an interesting topic; not only because visualizations are, in most cases, inviting and impressive to the human eye and brain. The main reason is that visual representations reveal different aspects of an issue in a systematic way, ranging from simple parliamentary information (such as voting records) to profound socio-political issues that lie behind shapes and colors. This article aims to explore some of the aspects related to the visualization of parliamentary information and activity.

Untangling the mystery behind visualized parliamentary information

Recent research on 19 PIV initiatives, presented in CeDEM 2014, has proven that visualizing parliamentary information is a complicated task. Its success depends on several factors: the availability of data and information, the choice of the visualization method, the intention behind the visualizations, and their effectiveness when these technologies are tied to a citizen engagement project.

To begin with, what has impressed us most during our research is the kind of information that was visualized. Characteristics, personal data and performance of Members of Parliament (MPs)/Members of European Parliament (MEPs), as well as political groups and member-states, are the elements most commonly visualized. On the other hand, particular legislative proposals, actions of MPs/MEPs through parliamentary control procedures and texts of legislation are less often visualized, which is, to some extent, understandable due to the complexity of visually depicting long legislative documents and the changes that accompany them.

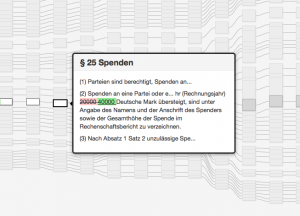

Gregor Aisch – The Making of a Law visualization

However, visually representing a legislative text and its amendments might possibly reveal important aspects of a bill, such as time of submission, specific modifications that have been performed, and additions or deleted articles and paragraphs in the text.

Another interesting aspect is the visualization method used. There is a variety of methods deployed even for the visualization of the same category of Parliamentary Informatics. Robert Kosara notes characteristically: “The seemingly simple choice between a bar and a line chart has implications on how we perceive the data”.

In the same line of thought, in a recent design camp of the Law Factory project, two designer groups independently combined data for law-making processes with an array of visualization methods, in order to bring forward different points of view of the same phenomenon. Indeed, one-method-fits-all approaches cannot be applied when it comes to parliamentary information visualization. A phenomenon can be visualized both quantitatively and qualitatively, and each method can bring different results. Therefore, visualizations can facilitate plain information or further explorations, depending on the aspirations of the designer. Enabling user information and exploration are, to some extent, the primary challenges set by PIV designers. However, not all visualization methods permit the same degree of exploration. Or sometimes, the ability of in-depth exploration is facilitated by providing further background information in order to help end users navigate, comprehend and interpret the visualization.

Beyond information and exploration

Surely, a visualization of MPs’ votes, characteristics, particular legislative proposals or texts of legislation can better inform citizens. But is it enough to make them empowered? The key to this question is interaction. Interaction whether in the sense of human-computer interaction or human-to-human interaction in a physical or digital context, always refers to a two-way procedure and effect. Schrage notes succinctly: “Don’t view visualization as a medium that substitutes pictures for words but as interfaces to human interactions that create new opportunities for new value creation.”

When it comes to knowledge gained through this exploration, it is understandable that knowledge is useless if it is not shared. This is a crucial challenge faced by visualization designers, because the creation of platforms that host visualizations and enable further exchange of views and dialogue between users can facilitate citizen engagement. Additionally, information sharing or information provision through an array of contemporary and traditional means (open data, social media, printing, e-mail etc.) can render PIV initiatives more complete and inclusive.

An issue of information representation, or information trustworthiness?

Beyond the technological and functional aspects of parliamentary information visualization, it is interesting to have a look into information management and the relationship between parliaments and Parliamentary Monitoring Organizations (PMOs). As also presented by a relevant survey, PMOs serve as a hub for presenting or monitoring the work of elected representatives, and seem to cover a wide range of activities concerning parliamentary development. This, however, might not always be easily acceptable by parliaments or MPs, since it may give to elected representatives a feeling of being surveilled by these organizations.

To further explain this, questions such as who owns vs. who holds parliamentary information, where and when is this information published, and to what ends, raise deeper issues of information originality, liability of information sources and trustworthiness of both the information and its owners. For parliaments and politicians, in particular, parliamentary information monitoring and visualization initiatives may be seen as a way to surveil their work and performance, whereas for PMOs themselves these initiatives can be seen as tools for pushing towards transparency of parliamentary work and accountability of elected representatives. This discussion is quite multi-faceted, and goes beyond the scope of this post. What should be kept in mind, however, is that establishing collaboration between politicians/parliaments and civil society surely requires time, effort, trust and common understanding from all the parties involved. Under these conditions, PIV and PMO initiatives can serve as hubs that bring parliaments and citizens closer, with a view to forming a more trusted relationship.

Towards transparency?

Most PIV initiatives provide information in a way compliant with the principles of the Declaration on Parliamentary Openness. Openness is a necessary condition for transparency. But, then, what is transparency? Is it possible to come up with a definition that accommodates the whole essence of this concept?

Transparent labyrinth by Robert Morris, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City (Dezeen)

In this quest, it is important to consider that neither openness nor transparency can exist without access to information (ATI). Consequently, availability and accessibility of parliamentary information are fundamental prerequisites in order to apply any technology that will hopefully contribute to inform, empower and help citizens participate in public decision-making.

Apart from that, it is important to look back in the definition, essence and legal nature of Freedom of Information (FOI) and Right to Information (RTI) provisions, as these are stated in the constitution of each country. A closer consideration of the similarities and differences between the terms “Freedom” and “Right”, whose meanings we usually take for granted, can provide important insight for the dependencies between them. Clarifying the meaning and function of these terms in a socio-political system can be a helpful start towards unraveling the notion of transparency.

Still, one thing is for sure: being informed and educated on our rights as citizens, as well as on how to exercise them, is a necessity nowadays. Educated citizens are able not only to comprehend the information available, but also search further, participate and have their say in decision-making. The example of the Right to Know initiative in Australia, based on the Alaveteli open-source platform, is an example of such an effort. The PIV initiatives researched thus far have shown that citizen engagement is a hard-to-reach task, which requires constant commitment and strive through a variety of tools and actions. In the long run, the full potential and effectiveness of these constantly evolving initiatives remains to be seen. In this context, legislative transparency remains in itself an open issue with many interesting aspects yet to be explored.

The links provided in the post are indicative examples and do not intend to promote initiatives or written materials for commercial or advertising purposes.

Aspasia Papaloi is a civil servant in the IT and New Technologies Directorate of the Hellenic Parliament, a PhD Candidate at the Faculty of Communication and Media Studies of the University of Athens and a research fellow of the Laboratory of New Technologies in Communication, Education and the Mass Media, contributing as a Teaching Assistant. She holds an MA with specialization in ICT Management from the University of the Aegean in Rhodes and a Bachelor of Arts in German Language and Literature (Germanistik) from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Her research area involves e-Parliaments with a special focus on visualization for the achievement of transparency.

Aspasia Papaloi is a civil servant in the IT and New Technologies Directorate of the Hellenic Parliament, a PhD Candidate at the Faculty of Communication and Media Studies of the University of Athens and a research fellow of the Laboratory of New Technologies in Communication, Education and the Mass Media, contributing as a Teaching Assistant. She holds an MA with specialization in ICT Management from the University of the Aegean in Rhodes and a Bachelor of Arts in German Language and Literature (Germanistik) from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Her research area involves e-Parliaments with a special focus on visualization for the achievement of transparency.

Dimitris Gouscos is Assistant Professor with the Faculty of Communication and Media Studies of the University of Athens and a research fellow of the Laboratory of New Technologies in Communication, Education and the Mass Media, where he contributes to co-ordination of two research groups on Digital Media for Learning and Digital Media for Participation. His research interests evolve around applications of digital communication in open governance, participatory media, interactive storytelling and playful learning. More information available on http://www.media.uoa.gr/~gouscos.

Dimitris Gouscos is Assistant Professor with the Faculty of Communication and Media Studies of the University of Athens and a research fellow of the Laboratory of New Technologies in Communication, Education and the Mass Media, where he contributes to co-ordination of two research groups on Digital Media for Learning and Digital Media for Participation. His research interests evolve around applications of digital communication in open governance, participatory media, interactive storytelling and playful learning. More information available on http://www.media.uoa.gr/~gouscos.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.