It’s tempting to begin any discussion of digital preservation and law libraries with a mind-blowing statistic. Something to drive home the fact that the clearly-defined world of information we’ve known since the invention of movable type has evolved into an ephemeral world of bits and bytes, that it’s expanding at a rate that makes it nearly impossible to contain, and that now is the time to invest in digital preservation efforts.

It’s tempting to begin any discussion of digital preservation and law libraries with a mind-blowing statistic. Something to drive home the fact that the clearly-defined world of information we’ve known since the invention of movable type has evolved into an ephemeral world of bits and bytes, that it’s expanding at a rate that makes it nearly impossible to contain, and that now is the time to invest in digital preservation efforts.

But, at this point, that’s an argument that you and I have already heard. As we begin the second decade of the 21st century, we know with certainty that the digital world is ubiquitous because we ourselves are part of it. Ours is a world where items posted on blogs are cited in landmark court decisions, a former governor and vice-presidential candidate posts her resignation speech and policy positions to Facebook, and a busy 21st-century president is attached at the thumb to his Blackberry.

We have experienced an exhilarating renaissance in information, which, as many have asserted for more than a decade, is threatening to become a digital dark age due to technology obsolescence and other factors. There is no denying the urgent need for libraries to take on the task of preserving our digital heritage. Law libraries specifically have a critically important role to play in this undertaking. Access to legal and law-related information is a core underpinning of our democratic society. Every law librarian knows this to be true. (I believe it’s what drew us to the profession in the first place.)

We have experienced an exhilarating renaissance in information, which, as many have asserted for more than a decade, is threatening to become a digital dark age due to technology obsolescence and other factors. There is no denying the urgent need for libraries to take on the task of preserving our digital heritage. Law libraries specifically have a critically important role to play in this undertaking. Access to legal and law-related information is a core underpinning of our democratic society. Every law librarian knows this to be true. (I believe it’s what drew us to the profession in the first place.)

Frankly speaking, our current digital preservation strategies and systems are imperfect – and they most likely will never be perfected. That’s because digital preservation is a field that will be in a constant state of change and flux for as long as technology continues to progress. Yet, tremendous strides have been made over the past decade to stave off the dreaded digital dark age, and libraries today have a number of viable tools, services, and best practices at our disposal for the preservation of digital content.

Law libraries and the preservation of born-digital content

In 2008, Dana Neacsu, a law librarian at Columbia University Law School, and I decided to explore the extent to which law libraries were actively involved in the preservation of born-digital legal materials. So, we conducted a survey of digital preservation activity and attitudes among state and academic law libraries.

We found an interesting incongruity among our respondent population of library directors who represented 21 law libraries: less than 7 percent of the digital preservation projects being planned or underway at our respondents’ libraries involved the preservation of born-digital materials. The remaining 93 percent involved the preservation of digital files created through the digitization of print or tangible originals. Yet, by a margin of 2 to 1, our respondents expressed that they believed born-digital materials to be in more urgent need of preservation than print materials.

This finding raises an interesting question: If law librarians (at least those represented among our respondents) believe born-digital materials to be in more urgent need of preservation, why were the majority of digital preservation resources being invested in the preservation of files resulting from digitization projects?

I speculate that part of the problem is that we often don’t know where to start when it comes to preserving born-digital content. What needs to be preserved? What systems and formats should we use? How will we pay for it?

I speculate that part of the problem is that we often don’t know where to start when it comes to preserving born-digital content. What needs to be preserved? What systems and formats should we use? How will we pay for it?

What needs to be preserved? A few thoughts…

Determining what needs to be preserved is not as complicated as it may seem. The mechanisms for content selection and collection development that are already in place at most law libraries lend themselves nicely to prioritizing materials for digital preservation, as I have learned through the Georgetown Law Library’s involvement in The Chesapeake Project Legal Information Archive. A collaborative effort between Georgetown and partners at the State Law Libraries of Maryland and Virginia, The Chesapeake Project was established to preserve born-digital legal information published online and available via open-access URLs (as opposed to within subscription databases).

Determining what needs to be preserved is not as complicated as it may seem. The mechanisms for content selection and collection development that are already in place at most law libraries lend themselves nicely to prioritizing materials for digital preservation, as I have learned through the Georgetown Law Library’s involvement in The Chesapeake Project Legal Information Archive. A collaborative effort between Georgetown and partners at the State Law Libraries of Maryland and Virginia, The Chesapeake Project was established to preserve born-digital legal information published online and available via open-access URLs (as opposed to within subscription databases).

So, how did we approach selection for the digital archive? Within a broad, shared project collection scope (limited to materials that were law- or policy-related, digitally born, and published to the “free Web” per our Collection Plan) each library simply established its own digital archive selection priorities, based on its unique institutional mandates and the research needs of its users. Libraries have historically developed their various print collections in a similar manner.

The Maryland State Library focused on collecting documents relating to public-policy and legal issues affecting Maryland citizens. The Virginia State Library collected the online publications of the Supreme Court of Virginia and other entities within Virginia’s judicial branch of government. As an academic library, the Georgetown Law Library developed topical and thematic collection priorities based on research and educational areas of interest at the Georgetown University Law Center. (Previously, online materials selected for the Georgetown Law Library’s collection had been printed from the Web on acid-free paper, bound, cataloged, and shelved. Digital preservation offered an attractive alternative to this system.)

To build our topical digital archive collections, the Georgetown Law Library assembled a team of staff subject specialists to select content (akin to our collection development selection committee), and, to make things as simple as possible, submissions were made and managed using a Delicious bookmark account, which allowed our busy subject specialists to submit online content for preservation with only a few clicks.

As a research library, we preserved information published to the free Web under a claim of fair use. Permission from copyright holders was sought only for items published either outside of the U.S. or by for-profit entities. Taking our cues from the Internet Archive, we determined to respect the robots.txt protocol in our Web harvesting activities and provide rights holders with instructions for requesting the removal of their content from the archive.

As a research library, we preserved information published to the free Web under a claim of fair use. Permission from copyright holders was sought only for items published either outside of the U.S. or by for-profit entities. Taking our cues from the Internet Archive, we determined to respect the robots.txt protocol in our Web harvesting activities and provide rights holders with instructions for requesting the removal of their content from the archive.

Fear of duplicating efforts

We have, on occasion, knowingly added digital materials to our archive collection that were already within the purview of other digital preservation programs. There is a fear of duplicating efforts when it comes to digital preservation, but there is also a strong argument to be made for multiple, geographically dispersed entities maintaining duplicate preserved copies of important digital resources.

This philosophy, especially as relates to duplicating the digital-preservation efforts of the Government Printing Office, is currently being echoed among several Federal Depository Libraries (and prominently by librarians who contribute to the Free Government Information blog) who are supporting the concept of digital deposit to maintain a truly distributed Federal Depository Library Program. Should there ever be a catastrophic failure at GPO, or even a temporary loss of access (such as that caused by the PURL server crash last August), user access to government documents would remain uninterrupted, thanks to this distributed preservation network. Currently there are 156 academic law libraries listed as selective depositories on the Federal Depository Library Directory; each of these would be candidates for digital deposit should the program come to fruition.

This philosophy, especially as relates to duplicating the digital-preservation efforts of the Government Printing Office, is currently being echoed among several Federal Depository Libraries (and prominently by librarians who contribute to the Free Government Information blog) who are supporting the concept of digital deposit to maintain a truly distributed Federal Depository Library Program. Should there ever be a catastrophic failure at GPO, or even a temporary loss of access (such as that caused by the PURL server crash last August), user access to government documents would remain uninterrupted, thanks to this distributed preservation network. Currently there are 156 academic law libraries listed as selective depositories on the Federal Depository Library Directory; each of these would be candidates for digital deposit should the program come to fruition.

Libraries with perpetual access or post-cancellation access agreements with publishers may also find it worthwhile to invest in digital preservation activities that may be redundant. Some publishers offer easy post-cancellation access to purchased digital content via nonprofit initiatives such as Portico and LOCKSS, both of which function as digital preservation systems. Other publishers, however, may simply provide subscribers with a set of CDs or DVDs containing their purchased subscription content. In these cases, it is worthwhile to actively preserve these files within a locally managed digital archive to ensure long-term accessibility for library patrons, rather than relegating these valuable digital files, stored on an unstable optical medium, to languishing on a shelf.

Law reviews and legal scholarship

It has been suggested that academic law libraries take responsibility for the preservation of digital content cited within their institutions’ law reviews to ensure that future researchers will able to reference source materials even if they are no longer available at the cited URLs. While there aren’t specific figures relating to the problem of citation link rot in law reviews, research on Web citations appearing in scientific journals has shown that roughly 10 percent of these citations become inactive within 15 months of the citing article’s publication. When it comes to Web-published law and policy information, our own Chesapeake Project evaluation efforts have found that about 14 percent, or 1 out of every 7, Web-based items had disappeared from their original URLs within two years of being archived.

It has been suggested that academic law libraries take responsibility for the preservation of digital content cited within their institutions’ law reviews to ensure that future researchers will able to reference source materials even if they are no longer available at the cited URLs. While there aren’t specific figures relating to the problem of citation link rot in law reviews, research on Web citations appearing in scientific journals has shown that roughly 10 percent of these citations become inactive within 15 months of the citing article’s publication. When it comes to Web-published law and policy information, our own Chesapeake Project evaluation efforts have found that about 14 percent, or 1 out of every 7, Web-based items had disappeared from their original URLs within two years of being archived.

In the near future, we may find ourselves in the position of taking responsibility for the digital preservation of our law reviews themselves, given the call to action in the Durham Statement on Open Access to Legal Scholarship. After all, if law schools end print publication of journals and commit “to keep the electronic versions available in stable, open, digital formats” within open-access online repositories, there is an implicit mandate to ensure that those repositories offer digital preservation functionality, or that a separate dark digital preservation system be used in conjunction with the repository, to ensure long-term access to the digital journal content. (It is important to note that digital repository software and services do not necessarily feature standard digital preservation functionality.)

Speaking of digital repositories, the responsibility for establishing and maintaining institutional repositories most certainly falls to the law library, as does the responsibility for preserving the digital intellectual output of their law schools’ faculty, institutes, centers, and students (many of whom go on to impressive heights).

Speaking of digital repositories, the responsibility for establishing and maintaining institutional repositories most certainly falls to the law library, as does the responsibility for preserving the digital intellectual output of their law schools’ faculty, institutes, centers, and students (many of whom go on to impressive heights).

At the Georgetown Law Library, we’ve also taken on the task of preserving the intellectual output published to the Law Center’s Web sites.

The Preserv project has compiled an impressive bibliography on digital preservation aimed specifically at preservation services for institutional repositories (but also covering many of the larger issues in digital preservation), which is worth reviewing.

What systems and formats should we use?

Did I mention that our current digital preservation strategies and systems are imperfect? Well, it’s true. That’s the bad news. No matter which system or service you chose, you will surely encounter occasional glitches, endure system updates and migrations, and be forced to revise your processes and workflows from time to time. This is a fledgling, evolving field, and it’s up to us to grow and evolve along with it.

Did I mention that our current digital preservation strategies and systems are imperfect? Well, it’s true. That’s the bad news. No matter which system or service you chose, you will surely encounter occasional glitches, endure system updates and migrations, and be forced to revise your processes and workflows from time to time. This is a fledgling, evolving field, and it’s up to us to grow and evolve along with it.

But, take heart! The good news is that there are standards and best practices established to guide us in developing strategies and selecting digital preservation systems, and we have multiple options to choose from. The key to embarking on a digital preservation project is to be versed in the language and standards of digital preservation, and to know what your options are.

The language and standards of digital preservation

I have heard a very convincing argument against standards in digital preservation: Because digital preservation is a new, evolving field, complying with rigid standards can be detrimental to systems that require a certain amount of adaptability in the face of emerging technological challenges. While I agree with this argument, I also believe that it is tremendously useful for those of us who are librarians, as opposed to programmers or IT specialists, to have standards as a starting point from which to identify and evaluate our options in digital preservation software and services.

There are a number of standards to be aware of in digital preservation. Chief among these is the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Reference Model, which provides the central framework for most work in digital preservation. A basic question to ask when evaluating a digital preservation system or service is, “Does this system conform to the OAIS model?” If not, consider that a red flag.

The Trustworthy Repositories Audit & Certification Criteria and Checklist, or TRAC, is a digital repository evaluation tool currently being incorporated into an international standard for auditing and certifying digital archives. A small number of large repositories have undergone (or are undergoing) TRAC audits, including E-Depot at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (National Library of the Netherlands), LOCKSS, Portico, and HathiTrust. This number can be expected to increase in the coming years.

The Trustworthy Repositories Audit & Certification Criteria and Checklist, or TRAC, is a digital repository evaluation tool currently being incorporated into an international standard for auditing and certifying digital archives. A small number of large repositories have undergone (or are undergoing) TRAC audits, including E-Depot at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (National Library of the Netherlands), LOCKSS, Portico, and HathiTrust. This number can be expected to increase in the coming years.

The TRAC checklist is also a helpful resource to consult in conducting your own independent evaluations. Last year, for example, the libraries participating in The Chesapeake Project commissioned the Center for Research Libraries to conduct an assessment (as opposed to a formal audit) of our OCLC digital archive system based on TRAC criteria, which provided useful information to strengthen the project.

The PREMIS Data Dictionary provides a core set of preservation metadata elements to support the long-term preservation and future renderability of digital objects stored within a preservation system. The PREMIS working group has created resources and tools to support PREMIS implementation, available via the Library of Congress’s Web site. It is useful to consult the data dictionary when establishing local policy, and to ask about PREMIS compatibility when evaluating digital preservation options.

While we’re on the exciting topic of metadata, the Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH, not to be confused with OAIS), is another protocol to watch for, especially if discovery and access are key components of your preservation initiative. OAI-PMH is a framework for sharing metadata between various “silos” of content. Essentially, the metadata of an OAI-PMH compliant system could be shared with and made discoverable via a single, federated search interface, allowing users to search the contents of multiple, distributed digital archives at the same time.

While we’re on the exciting topic of metadata, the Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH, not to be confused with OAIS), is another protocol to watch for, especially if discovery and access are key components of your preservation initiative. OAI-PMH is a framework for sharing metadata between various “silos” of content. Essentially, the metadata of an OAI-PMH compliant system could be shared with and made discoverable via a single, federated search interface, allowing users to search the contents of multiple, distributed digital archives at the same time.

For an easy-to-read overview of digital preservation practices and standards, I recommend Priscilla Caplan’s The Preservation of Digital Materials, which appeared in the Feb./March 2008 issue of Library Technology Reports. There are also a few good online glossaries available to help decipher digital preservation jargon: the California Digital Library Glossary, the Internet Archives’ Glossary of Web Archiving Terms, and the Digital Preservation Coalition’s Definitions and Concepts.

Open source formats and software

Open source and open standard formats and software play a vital role in the lifecycle management of digital content. In the context of digital preservation, open-source formats, which make their source code and specifications freely available, facilitate the future development of tools that can assist in the migration of files to new formats as technology progresses and older formats become obsolete. PDF, for example, although developed originally as a proprietary format by Adobe Systems, became a published open standard in 2008, meaning that developers will have a foundation for making these files accessible in the future.

Open source and open standard formats and software play a vital role in the lifecycle management of digital content. In the context of digital preservation, open-source formats, which make their source code and specifications freely available, facilitate the future development of tools that can assist in the migration of files to new formats as technology progresses and older formats become obsolete. PDF, for example, although developed originally as a proprietary format by Adobe Systems, became a published open standard in 2008, meaning that developers will have a foundation for making these files accessible in the future.

Other open source formats commonly used in digital preservation include the TIFF format for digital images, the ARC or WARC file for Web archiving, and the Extensible Markup Language (XML) text format for encoding data or document structure information. Microsoft formats, such as Word Documents, do not comply with open standards; the proprietary nature of these formats will inhibit future access to these documents when these formats become obsolete. The Library of Congress has a useful Web site devoted to digital formats and sustainability (including moving image and sound formats), which is worth reviewing.

Open source software is also looked upon favorably in digital preservation because, similar to open source formats, the software development and design process is made transparent, allowing current and future developers to develop new interfaces to or updates to the software over time.

Open source software is also looked upon favorably in digital preservation because, similar to open source formats, the software development and design process is made transparent, allowing current and future developers to develop new interfaces to or updates to the software over time.

Open source does not necessarily mean free-of-charge, and in fact, many service providers utilize open source software and open standards in developing fee-based or subscription digital preservation solutions.

Digital preservation solutions

There are many factors to consider in selecting a digital preservation solution. What is the nature of the content being preserved, and can the system accommodate it? Is preservation the sole purpose of the system — so that the system need include only a dark archive — or is a user access interface also necessary? How much does the system cost, and what are the expected ongoing maintenance costs, both in terms of budget and staff time? Is the system scalable, and can it accommodate a growing amount of content over time? This list could go on…

Keep in mind that no system will perfectly accommodate your needs. (Have I mentioned that digital preservation systems will always be imperfect?) And there is no use in waiting for the “perfect system” to be developed. We must use what’s available today. In selecting a system, consider its adherence to digital preservation standards, the stability of the institution or organization providing the solution, and the extent to which the digital preservation system has been accepted and adopted by institutions and user communities.

In a perfect world, perhaps every law library would implement a free, build-it-yourself, OAIS-compliant, open-source digital preservation solution with a large and supportive user community, such as DSpace or Fedora. These systems put full control in the hands of the libraries, which are the true custodians of the preserved digital content. But, in practice, our law libraries often do not have the staff and technological expertise to build and maintain an in-house digital preservation system.

In a perfect world, perhaps every law library would implement a free, build-it-yourself, OAIS-compliant, open-source digital preservation solution with a large and supportive user community, such as DSpace or Fedora. These systems put full control in the hands of the libraries, which are the true custodians of the preserved digital content. But, in practice, our law libraries often do not have the staff and technological expertise to build and maintain an in-house digital preservation system.

As a result, several reputable library vendors and nonprofit organizations have developed fee-based digital preservation solutions, often built using open-source software. The Internet Archive offers the Archive-It service for the preservation of Web sites. The Stanford University-based LOCKSS program provides a decentralized preservation infrastructure for Web-based and other types of digital content, and the MetaArchive Cooperative provides a preservation repository service using the open-source LOCKSS software. The Ex Libris Digital Preservation System and the collaborative HathiTrust repository both support the preservation of digital objects.

For The Chesapeake Project, the Georgetown, Maryland State, and Virginia State Law Libraries use OCLC systems: the Digital Archive for preservation, coupled with a hosted instance of CONTENTdm as an access interface.

In our experience, working with a vendor that hosted our content at a secure offsite location and managed system updates and migrations allowed us to focus our energies on the administrative and organizational aspects of the project, rather than the ongoing management of the system itself. We were able to develop shared project documentation, including preferred file format and metadata policies, and conduct regular project evaluations. Moreover, because our project was collaborative, it worked to our advantage to enlist a third party to store all three libraries’ content, rather than place the burden of hosting the project’s content upon one single institution. In short, working with a vendor can actually benefit your project.

In our experience, working with a vendor that hosted our content at a secure offsite location and managed system updates and migrations allowed us to focus our energies on the administrative and organizational aspects of the project, rather than the ongoing management of the system itself. We were able to develop shared project documentation, including preferred file format and metadata policies, and conduct regular project evaluations. Moreover, because our project was collaborative, it worked to our advantage to enlist a third party to store all three libraries’ content, rather than place the burden of hosting the project’s content upon one single institution. In short, working with a vendor can actually benefit your project.

The ultimate question: How will we pay for it?

We still seem to be in the midst of a global economic recession that has impacted university and library budgets. Yet, despite budget stagnation, there has been a steady increase in the production of digital content.

Digital preservation can be expensive, and law library staff members with digital preservation expertise are few. The logical solution to these issues of budget and staff limitations is to seek out opportunities for collaboration, which would allow for the sharing of costs, resources, and expertise among participating institutions.

Digital preservation can be expensive, and law library staff members with digital preservation expertise are few. The logical solution to these issues of budget and staff limitations is to seek out opportunities for collaboration, which would allow for the sharing of costs, resources, and expertise among participating institutions.

Collaborative opportunities exist with the Library of Congress, which has created a network of more than 130 preservation partners throughout the U.S., and the law library community is also in the process of establishing its own collaborative digital archive, the Legal Information Archive, to be offered through the Legal Information Preservation Alliance, or LIPA.

Collaborative opportunities exist with the Library of Congress, which has created a network of more than 130 preservation partners throughout the U.S., and the law library community is also in the process of establishing its own collaborative digital archive, the Legal Information Archive, to be offered through the Legal Information Preservation Alliance, or LIPA.

During the 2009 AALL annual meeting, LIPA’s executive director announced that The Chesapeake Project had become a LIPA-sanctioned project under the umbrella of the new Legal Information Archive. As a collaborative project with expenses shared by three law libraries, The Chesapeake Project’s costs are currently quite low compared to other annual library expenditures, such as those for subscription databases. These annual costs will decrease as more law libraries join this initiative.

I firmly believe that law libraries must invest in digital preservation if we are to remain relevant and true to our purpose in the 21st century. The core reason libraries exist is to build collections, to make those collections accessible, to assist patrons in using our collections, and to preserve our collections forever. No other institution has been created to take on this responsibility. Digital preservation represents an opportunity in the digital age for law libraries to reclaim their traditional roles as stewards of information, and to ensure that our digital legal heritage will be available to legal scholars and the public well into the future.

I firmly believe that law libraries must invest in digital preservation if we are to remain relevant and true to our purpose in the 21st century. The core reason libraries exist is to build collections, to make those collections accessible, to assist patrons in using our collections, and to preserve our collections forever. No other institution has been created to take on this responsibility. Digital preservation represents an opportunity in the digital age for law libraries to reclaim their traditional roles as stewards of information, and to ensure that our digital legal heritage will be available to legal scholars and the public well into the future.

Sarah Rhodes is the digital collections librarian at the Georgetown Law Library in Washington, D.C., and a project coordinator for The Chesapeake Project Legal Information Archive, a digital preservation initiative of the Georgetown Law Library in collaboration with the State Law Libraries of Maryland and Virginia.

Sarah Rhodes is the digital collections librarian at the Georgetown Law Library in Washington, D.C., and a project coordinator for The Chesapeake Project Legal Information Archive, a digital preservation initiative of the Georgetown Law Library in collaboration with the State Law Libraries of Maryland and Virginia.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor in Chief is Rob Richards.

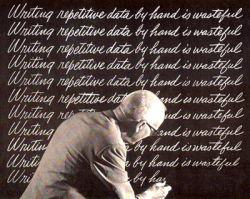

Because it is much simpler and faster to draft and manage amendments via an editor that takes care of everything, thus allowing drafters to concentrate on their essential activity: modifying the text.

Because it is much simpler and faster to draft and manage amendments via an editor that takes care of everything, thus allowing drafters to concentrate on their essential activity: modifying the text. re the cause of major headaches, no longer occurred.

re the cause of major headaches, no longer occurred. The slogan that best describes the strength of this XML editor is: “You are always just two clicks away from tabling an amendment!”

The slogan that best describes the strength of this XML editor is: “You are always just two clicks away from tabling an amendment!”![]() in a video conference with the United Nations Department for General Assembly and Conference Management from New York on 19 March 2013, Vice President Wieland announced, the UN/DESA’s Africa i-Parliaments Action Plan from Nairobi and the Senate of Italy from Rome, the availability of AT4AM for All, which is the name given to this open source version, for any parliament and institution interested in taking advantage of this well-oiled IT tool that has made the life of MEPs much easier.

in a video conference with the United Nations Department for General Assembly and Conference Management from New York on 19 March 2013, Vice President Wieland announced, the UN/DESA’s Africa i-Parliaments Action Plan from Nairobi and the Senate of Italy from Rome, the availability of AT4AM for All, which is the name given to this open source version, for any parliament and institution interested in taking advantage of this well-oiled IT tool that has made the life of MEPs much easier. Claudio Fabiani is Project Manager at the Directorate-General for Innovation and Tecnological Support of European Parliament. After an experience of several years in private sector as IT consultant, he started his career as civil servant at European Commission, in 2001, where he has managed several IT developments. Since 2008 he is responsible of AT4AM project and more recently he has managed the implementation of AT4AM for All, the open source version.

Claudio Fabiani is Project Manager at the Directorate-General for Innovation and Tecnological Support of European Parliament. After an experience of several years in private sector as IT consultant, he started his career as civil servant at European Commission, in 2001, where he has managed several IT developments. Since 2008 he is responsible of AT4AM project and more recently he has managed the implementation of AT4AM for All, the open source version.

Other large corporations, realizing the bias towards incremental innovation, have repeatedly resorted to radical steps to remedy the problem. They have established

Other large corporations, realizing the bias towards incremental innovation, have repeatedly resorted to radical steps to remedy the problem. They have established

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger