Take a look at your bundle of tags on Delicious. Would you ever believe you’re going to change the law with a handful of them?

You’re going to change the way you research the law. The way you apply it. The way you teach it and, in doing so, shape the minds of future lawyers.

Do you think I’m going too far? Maybe.

But don’t overlook the way taxonomies have changed the law and shaped lawyers’ minds so far. Taxonomies? Yeah, taxonomies.

We, the lawyers, have used extensively taxonomies through the years; Civil lawyers in particular have shown to be particularly prone to them. We’ve used taxonomies for three reasons: to help legal research, to help memorization and teaching, and to apply the law.

Taxonomies help legal research.

First, taxonomies help us retrieve what we’ve stored (rules and case law).

First, taxonomies help us retrieve what we’ve stored (rules and case law).

Are you looking for a rule about a sales contract? Dive deep into the “Obligations” category and the corresponding book (Recht der Schuldverhältnisse, Obbligazioni, Des contrats ou des obligations conventionnelles en général, you name it ).

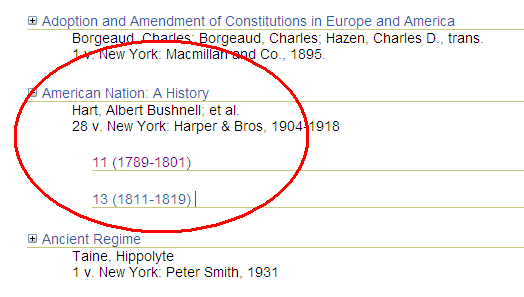

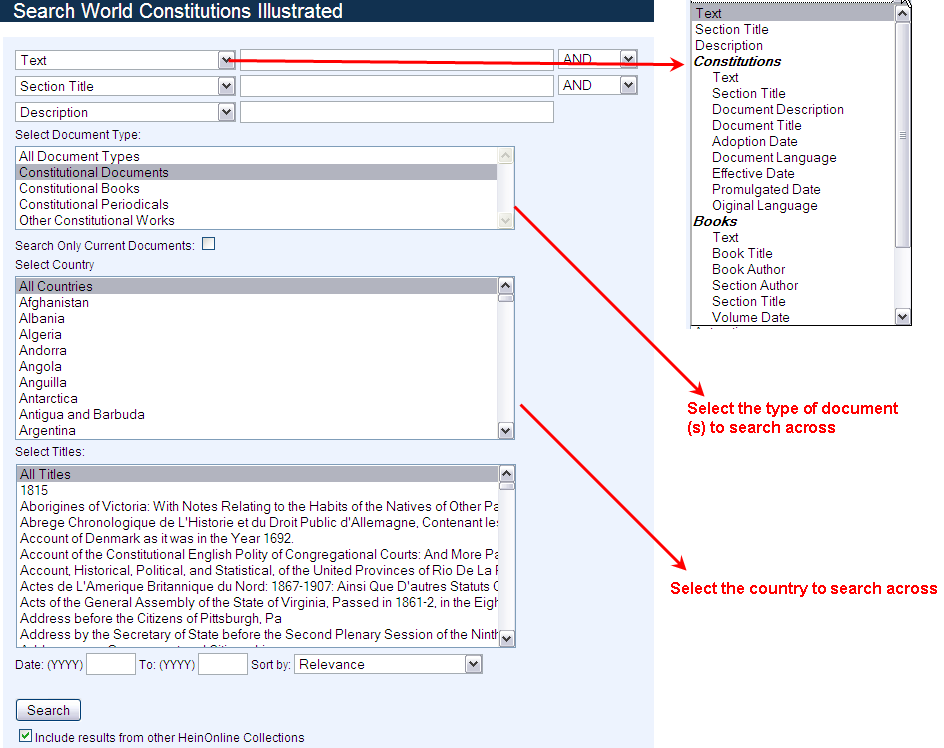

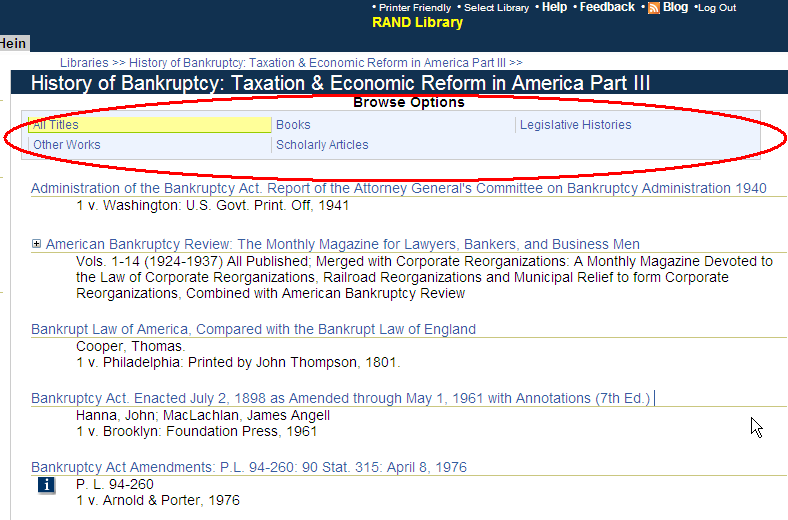

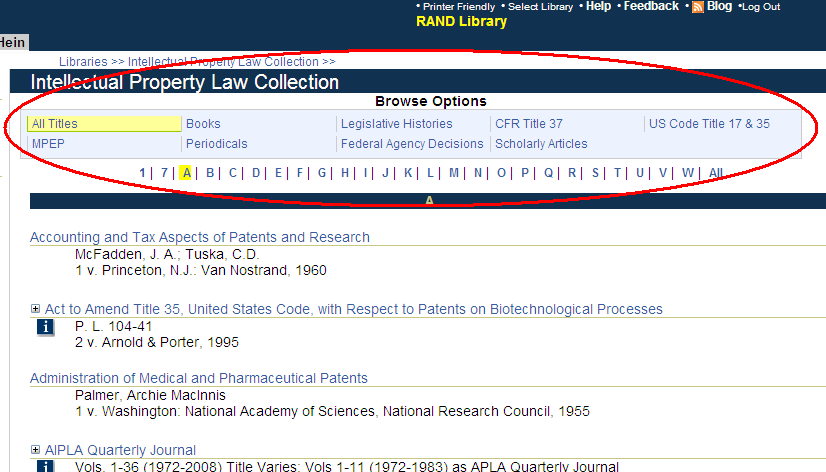

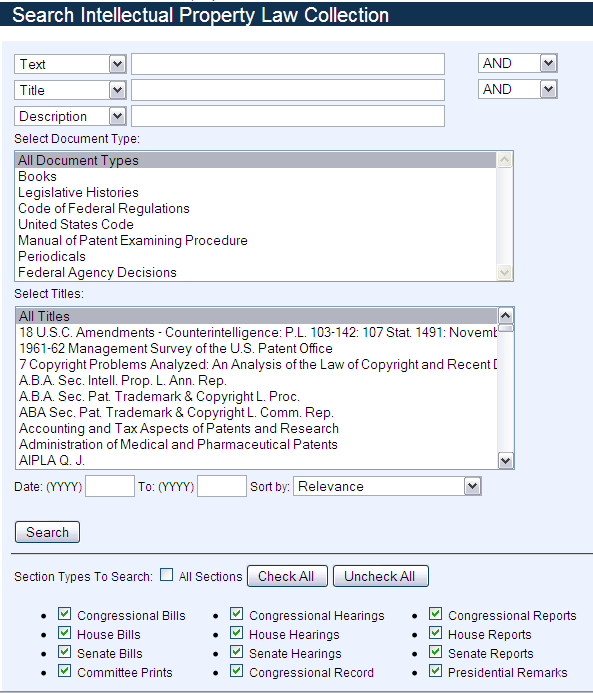

If you are a Common Lawyer, and ignore the perverse pleasure of browsing through Civil Code taxonomy, you’ll probably know Westlaw’s classification and its key numbering system. It has much more concrete categories and therefore much longer lists than the Civilians’ classification.

Legal taxonomies are there to help users find the content they’re looking for.

However, taxonomies sometimes don’t reflect the way the users reason; when this happens, you just won’t find what you’re looking for.

The problem with legal taxonomies.

If you are a German lawyer, you’ll probably be searching the “Obligations” book for rules concerning marriage; indeed in the German lawyer’s frame of mind, marriage is a peculiar form of contract. But if you are Italian, like I am, then you will most probably start looking in the “Persons” book; marriage rules are simply there, and we have been taught that marriage is not a contract but an agreement with no economic content (we have been trained to overlook the patrimonial shade in deference to the sentimental one).

So if I, the Italian, look for rules about marriage in the German civil code, I won’t find anything in the “Persons” book.

In other words, taxonomies work when they’re used by someone who reasons like the creator or–-and this happens with lawyers inside a certain legal system–-when users are trained to use the same taxonomy, and lawyers are trained at length.

But let’s take my friend Tim; he doesn’t have a legal education. He’s navigating Westlaw’s key number system looking for some relevant case law on car crashes. By chance he knows he should look below “torts,” but where? Is this injury and damage from act (k439)? Is this injury to a person in general (k425)? Is this injury to property or right of property in general (k429)? Wait, should he look below “crimes” (he is unclear on the distinction between torts and crimes)? And so on. Do these questions sound silly to you, the lawyers? Consider this: the titles we mentioned give no hint of the content, unless you already know what’s in there.

Because Law, complex as it is, needs a map. Lawyers have been trained to use the map. But what about non-lawyers?

In other words, the problems with legal taxonomies occur when the creators and the users don’t share the same frame of mind. And this is most likely to happen when the creators of the taxonomy are lawyers and the users are not lawyers.

Daniel Dabney wrote something similar some time ago. Let’s imagine that I buy a dog, take the little pooch home and find out that it’s mangy. Let’s imagine I’m that kind of aggressively unsatisfied customer and want to sue the seller, but know nothing about law. I go to the library and what will I look for? Rules on dogs sale? A book on Dog’s law? I’m lucky, there’s one, actually: “Dog law”, a book that gathers all laws regarding dogs and dogs owners.

But of course, that’s just luck, and if I had to browse through legal category in the Westlaw’s index, I would never have found anything regarding “dogs”. I will never find the word “dog”, which is nonetheless the first word a non-legal trained person would think of. A savvy lawyer would look for rules regarding sales and warranties: general categories I may not know of (or think of) if I’m not a lawyer. If I’m not a lawyer I may not know that “the sale of arguably defective dogs are to be governed by the same rules that apply to other arguably defective items, like leaky fountain pens”. Dogs are like pens for a lawyer, but they are just dogs for a dogs-owner: so a dogs owner will look for rules about dogs, not rules about sales and warranties (or at least he would look for sale of dogs). And dog law, a user aimed, object oriented category would probably fits his needs.

Observation #1: To make legal content available to everyone we must change the information architecture through which legal information are presented.

Will folksonomies make a better job?

Let’s come to folksonomies now. Here, the mismatch between creators (lawyers) and users’ way of reasoning is less likely to occur. The very same users decide which category to create and what to put into it. Moreover, more tags can overlap; that is, the same object can be tagged more than once. This allows the user to consider the same object from different perspectives. Take Delicious. If you search for “Intellectual property” on the Delicious search engine, you find a page about Copyright definition on Wikipedia. It was tagged mainly with “copyright.” But many users also tagged it with “wikipedia,” “law” and “intellectual-property” and even “art”. Maybe it was the non-lawyers out there who found it more useful to tag it with the “law” tag (a lawyer’s tag would have been more specific); maybe it was the lawyers who massively tagged it with “art” (there are a few “art” tags in their libraries). Or was it the other way around? The thing is, it’s up to users to decide where to classify it.

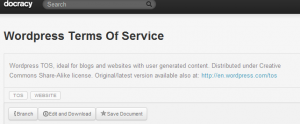

People also tag laws on Delicious using different labels that may or may not be related to law, because Delicious is a general-use website. But instead, let’s take a crowdsourced legal content website like Docracy. Here, people upload and tag their contracts, so it’s only legal content, and they tag them using only legal categories.

On Docracy, I found out that a whole category of documents that was dedicated to Terms of Service. Terms of Service is not a traditional legal category—-like torts, property, and contracts—-but it was a particularly useful category for Docracy users.

Docracy: WordPress Terms of Service are tagged with “TOS” but also with “Website”.

If I browse some more, I see that the WordPress TOS are also tagged with “website.” Right, it makes sense; that is, if I’m a web designer looking for the legal stuff I need to know before deploying my website. If I start looking just from “website,” I’ll find TOS, but also “contract of works for web design“ or “standard agreements for design services” from AIGA.

You got it? What legal folksonomies bring us is:

- User-centered categories

- Flexible categorization systems. Many items can be tagged more than once and so be put into different categories. Legal stuff can be retrieved through different routes but also considered under different lights.

Will this enhance findability? I think it will, especially if the users are non-lawyers. And services that target the low-end of the legal market usually target non-lawyers.

Alright, I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, oh no, again another naive folksonomy supporter! And then you say: “Folksonomie structures are too flat to constitute something useful for legal research!” and “Law is too a specific sector with highly technical vocabulary and structure. Non-legal trained users would just tag wrongly”.

Let me quickly address these issues.

Objection 1: Folksonomies are too flat to constitute something useful for legal research

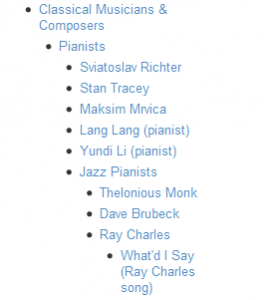

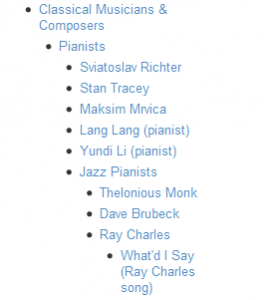

Let’s start from a premise: we have no studies on legal folksonomies yet. Docracy is not a full folksonomy yet ( users can tag but tags are pre-determined by administrators). But we do have examples of folksonomies tout court, so my argument moves analogically from them. Folksonomies do work. Take the Library of Congress Flickr project. Like an old grandmother, the Library gathered thousands of pictures that no-one ever had the time to review and categorize. So pictures were uploaded on Flickr and left for the users to tag and comment. They did it en masse, mostly by using descriptive or topical tags (non-subjective) that were useful for retrieval. If folksonomies work for pictures (Flickr), books (Goodreads), questions and answers (Quora), basically everything else (Delicious), why shouldn’t they work for law? Given that premise, let’s move to first objection: folksonomies are flat. Wrong. As folksonomies evolve, we find out that they can have two, three and even more levels of categories. Take a look at the Quora hierarchy.

That’s not flat. Look, there are at least four levels in the screenshot: Classical Musicians & Composers > Pianists > Jazz Pianists > Ray Charles > What’d I Say. Right, Jazz pianists are not classical musicians: but mistakes do occur and the good point in folksonomies is that users can freely correct them.

Second point: findability doesn’t depend only on hierarchies. You can browse the folksonomy’s categories but you can also use free text search to dig into it. In this case, users’ tags are metadata and so findability is enhanced because the search engine retrieves what users have tagged–not what admins have tagged.

Objection 2: Non-legal people will use the wrong tags

Uhm, yes, you’re right. They will tag a criminal law document with “tort” and a tort case involving a car accident with “car crash”. And so? Who cares? What if the majority of users find it useful? We forget too often that law is a social phenomenon, not a tool for technicians. And language is a social phenomenon too. If users consistently tag a legal document with the “wrong” tag X instead of the “right” tag Y, it means that they usually name that legal document with X. So most of them, when looking for that document, will look for X. And they’ll retrieve it, and be happy with that.

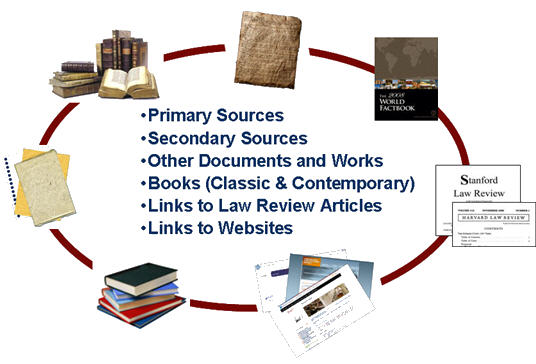

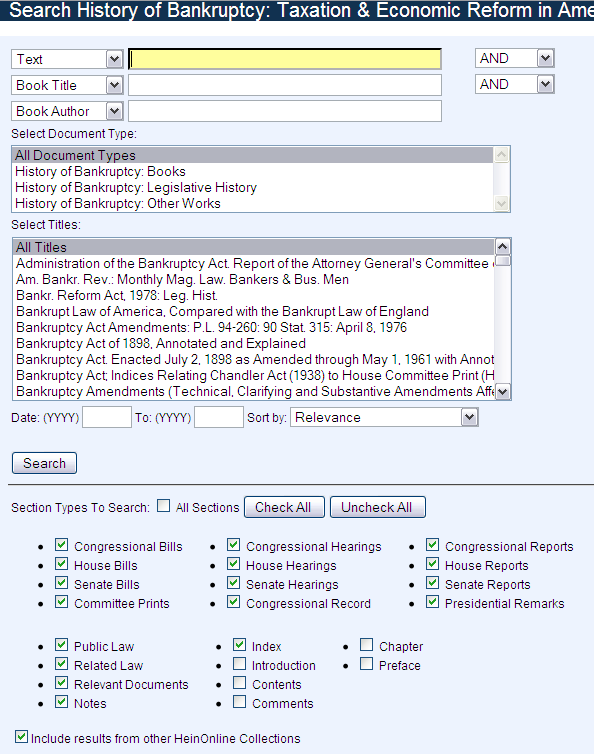

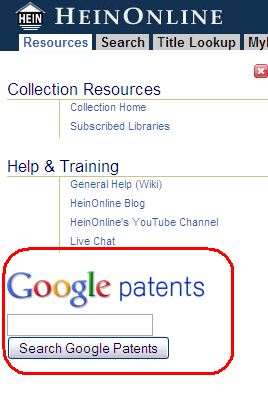

Of course, legal-savvy people would like to search by typical legal words (like, maybe, “chattel”?) or by using the legal categories they know so well. Do we want to compromise? The fact is, in a system where there is only user-generated content, it goes without saying that a traditional top-down taxonomy would not work. But if we have to imagine a system where content is not user-generated, like a legal or case law database, that could happen. There could be, for instance, a mixed taxonomy-folksonomy system where taxonomy is built with traditional legal terms and scheme, whereas folksonomy is built by the users who are free to tag. Search in the end, can be done by browsing the taxonomy, by browsing the folksonomy or by means of a search engine which fishes on content relying both on metadata chosen by system administrators and on metadata chosen by the users who tagged the content.

This may seem like an imaginary system–but it’s happening already. Amazon uses traditional categories and leave the users free to tag. The BBC website followed a similar pattern, moving from full taxonomy system to a hybrid taxonomy-folksonomy one. Resilience, resilience, as Andrea Resmini and Luca Rosati put it in their seminal book on information architecture. Folksonomies and taxonomies can coexist. But this is not what this article is about, so sorry for the digression and let’s move to the first prediction.

Prediction #1: Folksonomies will provide the right information architecture for non-legal users.

Taxonomies and folksonomies help legal teaching.

Secondly, taxonomies help us memorize rules and case law. Put all the things in a box and group them on the basis of a common feature, and you’ll easily remember where they are. For this reason, taxonomies have played a major role in legal teaching. I’ll tell you a little story. Civil lawyers know very well the story of Gaius, the ancient Roman jurist who created a successful taxonomy for his law handbook, the Institutiones. His taxonomy was threefold: all law can be divided into persons, things, and actions. Five centuries later (five centuries!) Emperor Justinian transferred the very same taxonomy into his own Institutiones, a handbook aimed at youth “craving for legal knowledge” (cupida legum iuventes). Why? Because it worked! How powerful, both the slogan and the taxonomy! Indeed more than 1000 years later, we found it again, with a few changes, in German, French, Italian, and Spanish Civil Codes and that, in a whole bunch of nutshells, explains private law following the taxonomy of the Codes.

Secondly, taxonomies help us memorize rules and case law. Put all the things in a box and group them on the basis of a common feature, and you’ll easily remember where they are. For this reason, taxonomies have played a major role in legal teaching. I’ll tell you a little story. Civil lawyers know very well the story of Gaius, the ancient Roman jurist who created a successful taxonomy for his law handbook, the Institutiones. His taxonomy was threefold: all law can be divided into persons, things, and actions. Five centuries later (five centuries!) Emperor Justinian transferred the very same taxonomy into his own Institutiones, a handbook aimed at youth “craving for legal knowledge” (cupida legum iuventes). Why? Because it worked! How powerful, both the slogan and the taxonomy! Indeed more than 1000 years later, we found it again, with a few changes, in German, French, Italian, and Spanish Civil Codes and that, in a whole bunch of nutshells, explains private law following the taxonomy of the Codes.

And now, consider what the taxonomies have done to lawyers’ minds.

Taxonomies have shaped their way of considering facts. Think. Put something into a category and you will lose all the other points of view on the same thing. The category shapes and limits our way to look at that particular thing.

Have you ever noticed how civil lawyers and common lawyers have a totally different way of looking at facts? Common lawyers see and take into account the details. Civil lawyers overlook them because the taxonomy they use has told them to do so.

In Rylands vs Fletcher (a UK tort case) some water escapes from a reservoir and floods a mine nearby. The owner of the reservoir could not possibly foresee the event and prevent it. However, the House of Lords states that the owner of the mine has the right to recover damages, even if there is no negligence. (“The person who for his own purpose brings on his lands and collects and keeps there anything likely to do mischief, if it escapes, must keep it in at his peril, and if he does not do so, is prima facie answerable for all the damage which is the natural consequence of its escape.”)

In Read vs Lyons, however, an employee gets injured during an explosion occurring in the ammunition factory where she is employed. The rule set in Rylands couldn’t be applied, as, according to the House of Lords, the case was very different; there is no escape.

On the contrary, for a Civil lawyer the decision would have been the same in both cases. For instance, under Italian Civil Code (but French and German Codes are not substantially different on this point), one would apply the general rule that grants reward for damages caused by “dangerous activities” and requires no proof of negligence on the plaintiff (art.2050 of the Civil Code), no matter what causes the danger (a big reservoir of water, an ammunition factory, whatever else).

Observation#2: taxonomies are useful for legal teaching and they shape lawyers minds.

Folksonomies for legal teaching?

Okay, and what about folksonomies? What if the way people tag legal concepts makes its way into legal teaching?

Take the Docracy‘s TOS category—have you ever thought about a course on TOS?

Another website, another example: Rocket Lawyer. Its categorization is not based on folksonomy, however; it’s purposely built around a user’s needs, which have been tested over the years, so in a way the taxonomy of the website comes from its users. One category is “identity theft”, which should be quite popular if it is prompted on the first page. What about teaching a course on identity theft? That would merge some material traditionally taught in privacy law, criminal law, and torts courses. Some course areas would overlap, which is good for memorization. Think again to the example of “Dog Law” by Dabney. What about a course about Dog Law, collecting material that refers to dogs across traditional legal categories?

Also, the same topic would be considered from different points of view.

What if students were trained to the specifications of the above-mentioned flexibility of categories? They wouldn’t get trapped into a single way of seeing things. If folksonomies account for different levels of abstractions, they would be trained to consider details. Not only that, they would develop a very flexible frame of mind.

Prediction #2: legal folksonomies in legal teaching would keep lawyers’ minds flexible.

Taxonomies and folksonomies SHAPE the law.

Third, taxonomies make the law apply differently. Think about it. They are the very highways that allow the law to travel down to us. And here it comes, the real revolutionary potential of legal folksonomies, if we were to make them work.

Third, taxonomies make the law apply differently. Think about it. They are the very highways that allow the law to travel down to us. And here it comes, the real revolutionary potential of legal folksonomies, if we were to make them work.

Let’s start from taxonomies, with a couple of examples.

Civil lawyers are taught that Public and Private Law are two distinctive areas of law, to which different rules apply. In common law, the distinction is not that clear-cut. In Rigby vs Chief Constable of Northamptonshire (a tort case from UK case law) the police—in an attempt to catch a criminal—damage a private shop by accidentally firing a canister of gas and setting the shop ablaze. The Queen’s Bench Division establishes that the police are liable under the tort of negligence only because the plaintiff manages to prove the police’s fault; they apply a private law category to a public body.

How would the same case have been decided under, say, French law? As the division between public and private law is stricter, the category of liability without fault, which is traditionally used when damages are caused by public bodies, would apply. The State would have to indemnify the damage, no matter if there was negligence.

Remember Rylands vs Fletcher and Lyons vs Read? The presence of escape/no escape was determinant, because the English taxonomy is very concrete. Civil lawyers work with taxonomies that have fewer, larger, and more abstract categories. If you cause damages by performing a risky activity, even if conducted without fault, you have to repay them. Period. Abstract taxonomy sweeps out any concrete detail. I think that Robert Berring had something like this in mind–although he referred to legal research–when he said that “classification defines the world of thinkable thoughts”. Or, as Dabney puts it, “thoughts that aren’t represented in the system had become unthinkable”.

So taxonomies make the law apply differently. In the former case, by setting a boundary between the public-private spheres; in the latter by creating a different framework for the application of more abstract or more detailed rules.

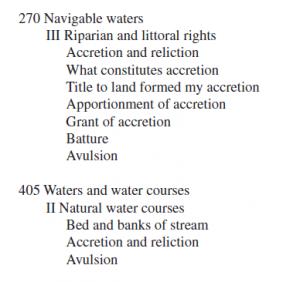

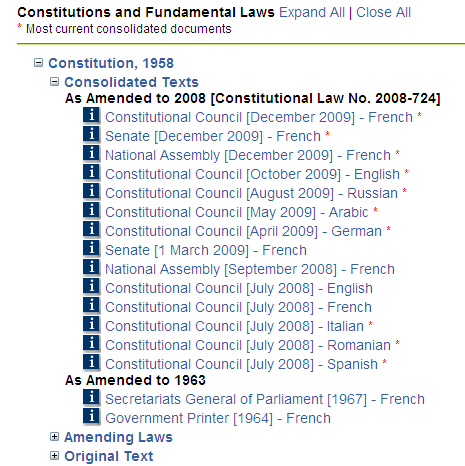

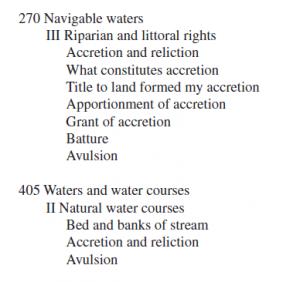

You don’t get it? All right, it’s tough, but do you have two minutes more? Let’s take this example by Dabney. Key number system’s taxonomy distinguishes between Navigable and Non-navigable waters (in the screenshot: waters and water courses). There’s a reason for that: lands under navigable waters presumptively belongs to the state, because “private ownership of the land under navigable waters would (…) compromise the use of those waters for navigation ad commerce”. So there are two categories because different laws apply to each. But now look at this screenshot.

Find anything strange? Yes: avulsion rules are “doubled”: they are contained in both categories. But they are the very same: rules concerning avulsion don’t change if the water is navigable or not (check avulsion definition if you, like me, don’t remember what it is ). Dabney: “In this context,(…) there is no difference in the legal rules that are applied that depend on whether or not the water is navigable. Navigability has an effect on a wide range of issues concerning waters, but not on the accretion/avulsion issue. Here, the organization of the system needlessly separates cases from each other on the basis of an irrelevant criterion”. And you think, ok, but as long as we are aware of this error and know the rules concerning avulsion are the same, it’s not biggie. Right, but in the future?

“If searchers, over time, find cases involving navigable waters in one place and non-navigable waters in another, there might develop two distinct bodies of law.” Got it? Dabney foresees it. The way we categorize the law would shape the way we apply it.

Observation #3 Different taxonomies entail different ways to apply the law.

So, what if we substitute taxonomies with folksonomies?

And what if they had the power to shape the way judges, legal scholars, lawmakers and legal operators think?

Legal folksonomies are just starting out, and what I envisage is still yet to come. Which makes this article kind of a visionary one, I admit.

However, what Docracy is teaching us is that users—I didn’t say lawyers, but users—are generating decent legal content. Would you have bet your two cents on this, say, five years ago?

What if users started generating new legal categories (legal folksonomies?)

Berring wrote something really visionary more than ten years ago in his beautiful “Legal Research and the World of Thinkable Thoughts”. He couldn’t have folksonomies in mind, and still, wouldn’t you think he referred to them when writing: “There is simply too much stuff to sort through. No one can write a comprehensive treatise any more, and no one can read all of the new cases. Machines are sorting for us. We need a new set of thinkable thoughts. We need a new Blackstone. We need someone, or more likely a group of someones, who can reconceptualize the structure of legal information.“?

Prediction #3 Legal folksonomies will make the law apply differently.

Let’s wait and see. Let the users tag. Where this tagging is going to take us is unpredictable, yes, but if you look at where taxonomies have taken us for all these years, you may find a clue.

I have a gut feeling that folksonomies are going to change the way we search, teach, and apply the law.

Serena Manzoli is a legal architect and the founder at WildLawyer, a design agency for law firms. She has been a Euro bureaucrat, a cadet, an in-house counsel, a bored lawyer. She holds an LLM from University of Bologna. She blogs at Lawyers are boring. Twitter: SquareLaw

Michael Curtotti is undertaking a PhD in the Research School of Computer Science at the Australian National University. His co-authored publications on legal informatics include: A Right to Access Implies a Right to Know: An Open Online Platform for Readability Research; Enhancing the Visualization of Law and A corpus of Australian contract language: description, profiling and analysis. He holds a Bachelor of Laws and a Bachelor of Commerce from the University of New South Wales, and a Masters of International Law from the Australian National University. He works part-time as a legal adviser to the ANU Students Association and the ANU Post-graduate & research students Association, providing free legal services to ANU students.

Michael Curtotti is undertaking a PhD in the Research School of Computer Science at the Australian National University. His co-authored publications on legal informatics include: A Right to Access Implies a Right to Know: An Open Online Platform for Readability Research; Enhancing the Visualization of Law and A corpus of Australian contract language: description, profiling and analysis. He holds a Bachelor of Laws and a Bachelor of Commerce from the University of New South Wales, and a Masters of International Law from the Australian National University. He works part-time as a legal adviser to the ANU Students Association and the ANU Post-graduate & research students Association, providing free legal services to ANU students.