Readers of this blog are probably already familiar with the U.S. Federal Courts’ system for electronic access called PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records). PACER is unlike any other country’s electronic public access system that I am aware of, because it provides complete access to docket text, opinions, and all documents filed (except sealed records, of course). It is a tremendously useful tool, and (at least at the time of its Web launch in the late 1990s) was tremendously ahead of its time.

However, PACER is unique in another important way: it imposes usage charges on citizens for downloading, viewing, and even searching for case materials. This limitation unfortunately forecloses a great deal of democracy-enhancing activity.

The PACER Liberation Front

The PACER Liberation Front

In 2008, I happened upon PACER in the course of trying to research a First Amendment issue. I am not a lawyer, but I was trying to get a sense of the federal First Amendment case law across all federal jurisdictions, because that case law had a direct effect on some activists at the time. I was at first excited that so much case law was apparently available online, but then disappointed when I discovered that the courts were charging for it. After turning over my credit card number to PACER, I was shocked that the system was charging for every single search I performed. With the type of research I was trying to do, it was inevitable that I would have to do countless searches to find what I was looking for. What’s more, the search functionality provided by PACER turned out to be nearly useless for the task at hand — there was no way to search for keywords, or within documents at all. The best I could do was pay for all the documents in particular cases that I suspected were relevant, and then try to sort through them on my own hard drive. Even this would be far from comprehensive.

This led to the inevitable conclusion that there is simply no way to know federal case law without going through a lawyer, doing laborious research using print legal resources, or paying for a high-priced database service. My only hope for getting use out of PACER was to find some way to affordably get a ton of documents. This is when I ran across a nascent project led by open government prophet Carl Malamud. He called it PACER Recycling. Carl offered to host any PACER documents that anybody happened to have, so that other people could download them. At that time, he had only a few thousand documents, but an ingenious plan: The federal courts were conducting a trial of free access at about sixteen libraries across the country. Anyone who walked in to one of those libraries and asked for PACER could browse and download documents for free. Carl was encouraging a “thumb drive corps” to bring USB sticks into those libraries and download caches of PACER documents.

The main bottleneck with this approach was volume. PACER contains hundreds of millions of documents, and manually downloading them all was just not going to happen. I had a weekend to kill, and an idea for building on his plan. I wrote up a Perl script that could run off of a USB drive and that would automatically start going through PACER cases and downloading all of the documents in an organized fashion. I didn’t live near one of the “free PACER” libraries, so I had to test the script using my own non-free PACER account… which got expensive. I began to contemplate the legal ramifications — if any — of downloading public records in bulk via this method. The following weekend I ran into Aaron Swartz.

Aaron is one of my favorite civic hackers. He’s a great coder and has a tendency to be bold. I told him about my little project, and he asked to see the code. He made some improvements and, given his higher tolerance for risk, proceeded to use the modified code to download about 2,700,000 files from PACER. The U.S. Courts freaked out, cancelled the free access trial, and said that “[t]he F.B.I. is conducting an investigation.” We had a hard time believing that the F.B.I. would care about the liberation of public records in a seemingly legal fashion, and told The New York Times as much. (Media relations pro tip: If you don’t want to be quoted, always, repeatedly emphasize that your comments are “on background” only. Even though I said this when I talked to The Times, they still put my name in the corresponding blog post. That was the first time I had to warn my fiancée that if the feds came to the door, she should demand a warrant.)

A few months later, Aaron got curious about whether the FBI was really taking this seriously. In a brilliantly ironic move, he filed a FOIA for his own FBI record, which was delivered in due course and included such gems as:

Between September 4, 2008 and September 22, 2008, PACER was accessed by computers from outside the library utilizing login information from two libraries participating in the pilot project. The Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts reported that the PACER system was being inundated with requests. One request was being made every three seconds.

[…] The two accounts were responsible for downloading more than eighteen million pages with an approximate value of $1.5 million.

The full thing is worth a read, and it includes details about the feds looking through Aaron’s Facebook and LinkedIn profiles. However, the feds were apparently unable to determine Aaron’s current residence and ended up staking out his parents’ house in Illinois. The feds had to call off the surveillance because, in their words: “This is a heavily wooded, dead-end street, with no other cars parked on the road making continued surveillance difficult to conduct without severely increasing the risk of discovery.” The feds eventually figured out Aaron wasn’t in Illinois when he posted to Facebook: “Want to meet the man behind the headlines? Want to have the F.B.I. open up a file on you as well? Interested in some kind of bizarre celebrity product endorsement? I’m available in Boston and New York all this month.” They closed the case.

Turning PACER Around

Turning PACER Around

Carl published Aaron’s trove of documents (after conducting a very informative privacy audit), but the question was: what to do next? I had long given up on my initial attempt to merely understand a narrow aspect of First Amendment jurisprudence, and had taken up the PACER liberation cause wholeheartedly. At the time, this consisted of writing about the issue and giving talks. I ran across a draft article by some folks at Princeton called “Government Data and the Invisible Hand.” It argued:

Rather than struggling, as it currently does, to design sites that meet each end-user need, we argue that the executive branch should focus on creating a simple, reliable and publicly accessible infrastructure that exposes the underlying data. Private actors, either nonprofit or commercial, are better suited to deliver government information to citizens and can constantly create and reshape the tools individuals use to find and leverage public data.

I couldn’t have agreed more, and their prescription for the executive branch made sense for the brain-dead PACER interface too. I called up one of the authors, Ed Felten, and he told me to come down to Princeton to give a talk about PACER. Afterwards, two graduate students, Harlan Yu and Tim Lee, came up to me and made an interesting suggestion. They proposed a Firefox extension that anyone using PACER could install. As users paid for documents, those documents would automatically be uploaded to a public archive. As users browsed dockets, if any documents were available for free, the system would notify them of that, so that the users could avoid charges. It was a beautiful quid-pro-quo, and a way to crowdsource the PACER liberation effort in a way that would build on the existing document set.

So Harlan and Tim built the extension and called it RECAP (tagline: “Turning PACER around” Get it? eh?). It was well received, and you can read the great endorsements from The Washington Post, The L.A. Times, The Guardian, and many like-minded public interest organizations. The courts freaked out again, but ultimately realized they couldn’t go after people for republishing the public record.

I helped with a few of the details, and eventually ended up coming down to work at their research center, the Center for Information Technology Policy. Last year, a group of undergrads built a fantastic web interface to the RECAP database that allows better browsing and searching than PACER. Their project is just one example of the principle laid out in the “Government Data and the Invisible Hand” paper: when presented with the raw data, civic hackers can build better interfaces to that data than the government.

From Fee to Free

From Fee to Free

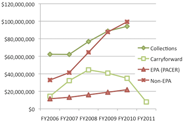

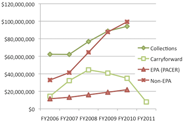

Despite all of our efforts, the database of free PACER materials still contains only a fraction of the documents stored in the for-fee database. The real end-game is for the courts to change their mind about the PACER paywall approach in the first place. We have made this case in many venues. Influential senators have sent them letters. I have even pointed out that the courts are arguably violating The 2002 E-Government Act. As it happens, PACER brings in over $100 million annually through user fees. These fees are spent partially on supporting PACER’s highly inefficient infrastructure, but are also partially spent on various other things that the courts deem somehow related to public access. This includes what one judge described as expenditures on his courtroom:

“Every juror has their own flatscreen monitors. We just went through a big upgrade in my courthouse, my courtroom, and one of the things we’ve done is large flatscreen monitors which will now — and this is a very historic courtroom so it has to be done in accommodating the historic nature of the courthouse and the courtroom — we have flatscreen monitors now which will enable the people sitting in the gallery to see these animations that are displayed so they’re not leaning over trying to watch it on the counsel table monitor. As well as audio enhancements. In these big courtrooms with 30, 40 foot ceilings where audio gets lost we spent a lot of money on audio so the people could hear what’s going on. We just put in new audio so that people — I’d never heard of this before — but it actually embeds the speakers inside of the benches in the back of the courtroom and inside counsel tables so that the wood benches actually perform as amplifiers.”

I am not against helping courtroom visitors hear and see trial testimony, but we must ask whether it is good policy to restrict public access to electronic materials on the Internet in the name of arbitrary courtroom enhancements (even assuming that allocating PACER funds to such enhancements is legal, which is questionable). The real hurdle to liberating PACER is that it serves as a cross-subsidy to other parts of our underfunded courts. I parsed a bunch of appropriations data and committee reports in order to write up a report on actual PACER costs and expenditures. What is just as shocking as the PACER income’s being used for non-PACER expenses, is the actual claimed cost of running PACER, which is orders of magnitude higher than any competent Web geek would tell you it should be (especially for a system whose administrators once worried that “one request was being made every three seconds.”). The rest of the federal government has been moving toward cloud-based “Infrastructure as a Service”, while the U.S. Courts continue to maintain about 100 different servers in each jurisdiction, each with their own privately leased internet connection. (Incidentally, if you enjoy conspiracy theories, try to ID the pseudonymous “Schlomo McGill” in the comments of this post and this post.)

The ultimate solution to the PACER fee problem unfortunately lies not in exciting spy-vs-spy antics (although those can be helpful and fun), but in bureaucratic details of authorization subcommittees and technical details of network architecture. This is the next front of PACER liberation. We now have friends in Washington, and we understand the process better every day. We also have very smart geeks, and I think that the ultimate finger on the scale may be our ability to explain how the U.S. Courts could run a tremendously more efficient system that would simultaneously generate a diversity of new democratic benefits. We also need smart librarians and archivists making good policy arguments. That is one reason why the Law.gov movement is so exciting to me. It has the potential not only to unify open-law advocates, but to go well beyond the U.S. Federal Case Law fiefdom of PACER.

Perhaps then I can finally get the answer to that narrow legal question I tried to ask in 2008. I’m sure that the answer will inevitably be: “It’s complicated.”

Steve Schultze is Associate Director of The Center for Information Technology Policy at Princeton. His work includes Internet privacy, security, government transparency, and telecommunications policy. He holds degrees in Computer Science, Philosophy, and Media Studies from Calvin College and MIT. He has also been a Fellow at The Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard, and helped start the Public Radio Exchange.

Steve Schultze is Associate Director of The Center for Information Technology Policy at Princeton. His work includes Internet privacy, security, government transparency, and telecommunications policy. He holds degrees in Computer Science, Philosophy, and Media Studies from Calvin College and MIT. He has also been a Fellow at The Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard, and helped start the Public Radio Exchange.

Just over one month ago, #freeTHOMAS reached a fever pitch surrounding the passage of H.R. 5882, the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act for FY2013. Just before passage, H.Rpt.511 directed official conversation on open legislative data for the coming fiscal year by saying, “let’s talk.” In a section about the Government Printing Office, the House Appropriations Committee expressed concerns about authentication and open legislative data, but called for a task force “composed of staff representatives of the Library of Congress, the Congressional Research Service, the Clerk of the House, the Government Printing Office, and such other congressional offices as may be necessary,” to look in to the matter.

Just over one month ago, #freeTHOMAS reached a fever pitch surrounding the passage of H.R. 5882, the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act for FY2013. Just before passage, H.Rpt.511 directed official conversation on open legislative data for the coming fiscal year by saying, “let’s talk.” In a section about the Government Printing Office, the House Appropriations Committee expressed concerns about authentication and open legislative data, but called for a task force “composed of staff representatives of the Library of Congress, the Congressional Research Service, the Clerk of the House, the Government Printing Office, and such other congressional offices as may be necessary,” to look in to the matter.

Librarians are foot soldiers for the First Amendment–we like open information, we place a high value on the freedom to know. However, we’re among the first to be cut in tight budget situations, and we’re all too familiar with the perils of asking for something that’s overly broad, or asking for something that you can’t show narrowly tailored value for later on.

Librarians are foot soldiers for the First Amendment–we like open information, we place a high value on the freedom to know. However, we’re among the first to be cut in tight budget situations, and we’re all too familiar with the perils of asking for something that’s overly broad, or asking for something that you can’t show narrowly tailored value for later on. Meg Lulofs is an information professional at large, blogging at librarylulu.com, editing Pimsleur’s Checklists of Basic American Legal Publications, and making mischief. She earned a J.D. from the University of Baltimore, and a M.L.I.S. from Catholic University. She welcomes feedback at meglulofs@gmail.com. You can follow her on Twitter @librarylulu, or on Facebook at facebook.com/librarylulu.

Meg Lulofs is an information professional at large, blogging at librarylulu.com, editing Pimsleur’s Checklists of Basic American Legal Publications, and making mischief. She earned a J.D. from the University of Baltimore, and a M.L.I.S. from Catholic University. She welcomes feedback at meglulofs@gmail.com. You can follow her on Twitter @librarylulu, or on Facebook at facebook.com/librarylulu.