The other day a friend came to me because he heard about the openlaws.eu project. He said: “Hey, openlaws sounds great – does that mean that I can write my own laws now?”. I had to tell him no, but that it was almost as good as that… Continue reading »

VoxPopuLII

AT4AM – Authoring Tool for Amendments – is a web editor provided to Members of European Parliament (MEPs) that has greatly improved the drafting of amendments at European Parliament since its introduction in 2010.

The tool, developed by the Directorate for Innovation and Technological Support of European Parliament (DG ITEC) has replaced a system based on a collection of macros developed in MS Word and specific ad hoc templates.

Why move to a web editor?

The need to replace a traditional desktop authoring tool came from the increasing complexity of layout rules combined with a need to automate several processes of the authoring/checking/translation/distribution chain.

In fact, drafters not only faced complex rules and had to search among hundreds of templates in order to get the right one, but the drafting chain for all amendments relied on layout to transmit information down the different processes. Bold / Italic notation or specific tags were used to transmit specific information on the meaning of the text between the services in charge of subsequent revision and translation.

Over the years, an editor that was initially conceived to support mainly the printing of documents was often used to convey information in an unsuitable manner. During the drafting activity, documents transmitted between different services included a mix of content and layout where the layout sometime referred to some information on the business process that should rather be transmitted via other mediums.

Moreover, encapsulating in one single file all the amendments drafted in 23 languages was a severe limitation for subsequent revisions and translations carried out by linguistic sectors. Experts in charge of legal and linguistic revision of drafted amendments, who need to work in parallel on one document grouping multilingual amendments, were severely hampered in their work.

All the needs listed above justified the EP undertaking a new project to improve the drafting of amendments. The concept was soon extended to the drafting, revision, translation and distribution of the entire legislative content in the European Parliament, and after some months the eParliament Programme was initiated to cover all projects of the parliamentary XML-based drafting chain.

It was clear from the beginning that, in order to provide an advanced web editor, the original proposal to be amended had to be converted into a structured format. After an extensive search, XML Akoma Ntoso format was chosen, because it is the format that best covers the requirements for drafting legislation. Currently it is possible to export amendments produced via AT4AM in Akoma Ntoso. It is planned to apply Akoma Ntoso schema to the entire legislative chain within eParliament Programme. This will enable EP to publish legislative texts in open data format.

What distinguishes the approach taken by EP from other legislative actors who handle XML documents is the fact that EP decided to use XML to feed the legislative chain rather than just converting existing documents into XML for distribution. This aspect is fundamental because requirements are much stricter when the result of XML conversion is used as the first step of legislative chain. In fact, the proposal coming from European Commission is first converted in XML and after loaded into AT4AM. Because the tool relies on the XML content, it is important to guarantee a valid structure and coherence between the language versions. The same articles, paragraphs, point, subpoints must appear at the correct position in all the 23 language versions of the same text.

What is the situation now?

After two years of intensive usage, Members of European Parliaments have drafted 285.000 amendments via AT4AM. The tool is also used daily by the staff of the secretariat in charge of receiving tabled amendments, checking linguistic and legal accuracy and producing voting lists. Today more then 2300 users access the system regularly, and no one wants to go back to the traditional methods of drafting. Why?

Because it is much simpler and faster to draft and manage amendments via an editor that takes care of everything, thus allowing drafters to concentrate on their essential activity: modifying the text.

Because it is much simpler and faster to draft and manage amendments via an editor that takes care of everything, thus allowing drafters to concentrate on their essential activity: modifying the text.

Soon after the introduction of AT4AM, the secretariat’s staff who manage drafted amendments breathed a sigh of relief, because errors like wrong position references, which we re the cause of major headaches, no longer occurred.

re the cause of major headaches, no longer occurred.

What is better than a tool that guides drafters through the amending activity by adding all the surrounding information and taking care of all the metadata necessary for subsequent treatment, while letting the drafter focus on the text amendments and produce well-formatted output with track changes?

After some months of usage, it was clear that not only the time to draft, check and translate amendments was drastically reduced, but also the quality of amendments increased.

The slogan that best describes the strength of this XML editor is: “You are always just two clicks away from tabling an amendment!”

The slogan that best describes the strength of this XML editor is: “You are always just two clicks away from tabling an amendment!”

Web editor versus desktop editor: is it an acceptable compromise?

One of the criticisms that users often raise against web editors is that they are limited when compared with a traditional desktop rich editor. The experience at the European Parliament has demonstrated that what users lose in terms of editing features is highly compensated by the gains of getting a tool specifically designed to support drafting activity. Moreover, recent technologies enable programmers to develop rich web WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) editors that include many of the traditional features plus new functions specific to a “networking” tool.

What’s next?

The experience of EP was so positive and so well received by other Parliaments that in May 2012, at the opening of the international workshop “Identifying benefits deriving from the adoption of XML-based chains for drafting legislation“, Vice President Wieland announced the launch of a new project aimed at to providing an open source version of the AT4AM code.

![]() in a video conference with the United Nations Department for General Assembly and Conference Management from New York on 19 March 2013, Vice President Wieland announced, the UN/DESA’s Africa i-Parliaments Action Plan from Nairobi and the Senate of Italy from Rome, the availability of AT4AM for All, which is the name given to this open source version, for any parliament and institution interested in taking advantage of this well-oiled IT tool that has made the life of MEPs much easier.

in a video conference with the United Nations Department for General Assembly and Conference Management from New York on 19 March 2013, Vice President Wieland announced, the UN/DESA’s Africa i-Parliaments Action Plan from Nairobi and the Senate of Italy from Rome, the availability of AT4AM for All, which is the name given to this open source version, for any parliament and institution interested in taking advantage of this well-oiled IT tool that has made the life of MEPs much easier.

The code has been released under EUPL(European Union Public Licence), an open source licence provided by European Commission that is compatible with major open source licences like Gnu GPLv2 with the advantage of being available in the 22 official languages of the European Union.

AT4AM for All is provided with all the important features of the amendment tool used in the European Parliament and can manage all type of legislative content provided in the XML format Akoma Ntoso. This XML standard, developed through the UN/DESA’s initiative Africa i-Parliaments Action Plan, is currently under certification process at OASIS, a non-profit consortium that drives the development, convergence and adoption of open standards for the global information society. Those who are interested may have a look to the committee in charge of the certification: LegalDocumentML

Currently the Documentation Division, Department for General Assembly and Conference Management of United Nations is evaluating the software for possible integration in their tools to manage UN resolutions.

The ambition of EP is that other Parliaments with fewer resources may take advantage of this development to improve their legislative drafting chain. Moreover, the adoption of such tools allows a Parliament to move towards an XML based legislative chain. The distribution of legislative content in open document formats like XML allows other parties to treat in an efficient way the legislation produced.

Thanks to the efforts of European Parliament, any parliament in the world is now able to use the advanced features of AT4AM to support the drafting of amendments. AT4AM will serve as a useful tool for all those interested in moving towards open data solutions and more democratic transparency in the legislative process.

At AT4AM for All website it is possible to get the status of works and run a sample editor with several document types. Any Parliament interested can go to the repository and download the code.

Claudio Fabiani is Project Manager at the Directorate-General for Innovation and Tecnological Support of European Parliament. After an experience of several years in private sector as IT consultant, he started his career as civil servant at European Commission, in 2001, where he has managed several IT developments. Since 2008 he is responsible of AT4AM project and more recently he has managed the implementation of AT4AM for All, the open source version.

Claudio Fabiani is Project Manager at the Directorate-General for Innovation and Tecnological Support of European Parliament. After an experience of several years in private sector as IT consultant, he started his career as civil servant at European Commission, in 2001, where he has managed several IT developments. Since 2008 he is responsible of AT4AM project and more recently he has managed the implementation of AT4AM for All, the open source version.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.

On a Legal Framework in a Virtual World: Lessons from the VirtualLife Project

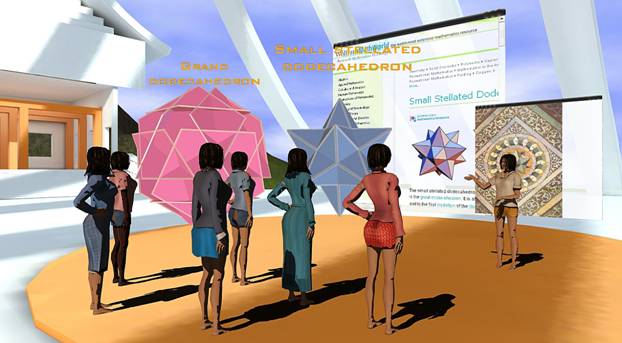

In this article, I reflect on the legal frameworks that affect virtual worlds. In particular, I focus on the use of non-game three-dimensional online virtual worlds such as Second Life, for purposes of education and training. These worlds are also known as “serious” games. Pictured below is an example of such a “serious” game: a possible learning support scenario — interacting with a complex 3D geometric object, in the context of a geometry lesson within a virtual world.

The European Union Information and Communication Technologies Seventh Framework Programme, FP7 ICT, has funded a VirtualLife consortium of ten partners that plans to create a secure and legally ruled virtual world platform. The legal framework they are constructing includes a novel, editable, and enforceable Virtual Constitution. This article describes the legal framework of VirtualLife, using material from several VirtualLife project deliverables: a presentation and publications, primarily Bogdanov et al. (2009), and Čyras & Lachmayer (2010).

The problem of law enforcement in virtual worlds

The rules of games, such as chess, can be programmed. However, this is not the case for legal rules contained in a code of conduct in a virtual constitution. Moreover, in a code of conduct for a virtual world, we supplement the normal concept of “persons” who are subject to law, with the concept of “avatars” — that is, the virtual persons used to navigate a virtual world. This variety of rules, which applies to avatars, is called “virtual law” (see Raph Koster). A sample “toy” rule, such as “Keep off the grass,” illustrates constraints on avatar conduct, constraints aimed primarily at preventing unwanted behaviour.

Various methods of norm enforcement by computers are being investigated worldwide (see, e.g., Vázquez-Salceda et al. (2008)). Lawrence Lessig‘s Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace (1999, updated in 2005) noted that cyberspace would be controlled — or not — depending upon the architecture, or “code,” of that space.

A general frame of a virtual world

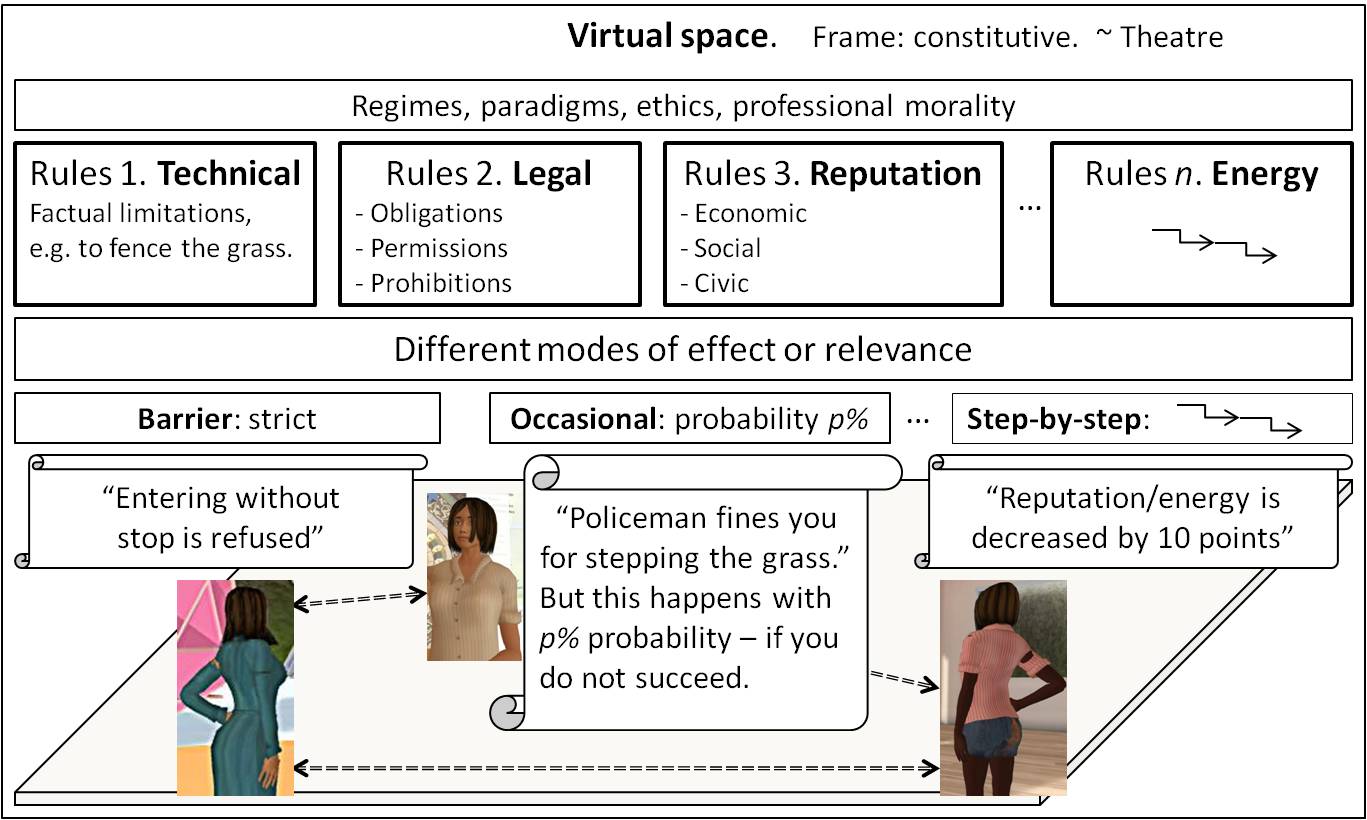

A general sketch of virtual world legal issues, as described by legal scholar Friedrich Lachmayer, is outlined below. It differs from the view of software engineers. Many legal rules in a virtual world are described informally. The entities of major importance are avatar actions and the rules that regulate their behaviour. Here is a conceptualisation of the “theatre” depicting the elements of a virtual world and the principles of construction of its legal framework:

Rules can form different normative systems within a virtual world, as well as a regime, or paradigm, of a virtual world. The rules in a virtual world can have different modes or degrees of effectiveness, such as “barrier,” “occasional,” “step-by-step,” etc. Moreover, these rules can be divided into different classes, such as technical rules, legal rules, reputation rules, energy rules, and professional rules:

- Technical rules establish factual limitations. Real world examples include fencing in a plot of grass, locking a door to forbid entry, and an automatic teller machine’s refusing to dispense money unless a PIN code is provided. Violations of technical rules are impossible: there is no possibility of violating a technical rule unless you break the artifact completely (e.g., by cutting the fence, or breaking down the door). Hence technical rules are strictly enforceable. They are based on natural necessity and can be formalised as: “If P then Q.” They do not have modes or degrees of effectiveness such as “obligatory,” “permitted,” and “forbidden.”

- Legal rules. Their nature is that they can be violated. For example, you can jaywalk, but you risk being sanctioned. These laws are enforced by an authority such as the police, or peacekeepers in a virtual world. Legal rules are not strictly enforceable, and their enforcement may be subject to the so-called “spirit,” or purpose, of the law.

Legal rules are necessary, because it is impossible to implement normative regulation by means of technical rules alone. Consider a norm providing that indecent content is prohibited in the virtual world. Such an abstract norm can hardly be implemented by automatic checking. A naked body should not be automatically treated as indecent content, because it may be a picture of a statue in a virtual museum.

- Energy rules prohibit certain kinds of behaviour. If energy rules are violated, the violator’s “energy points” are decreased. Such sanctions are 100% effective.

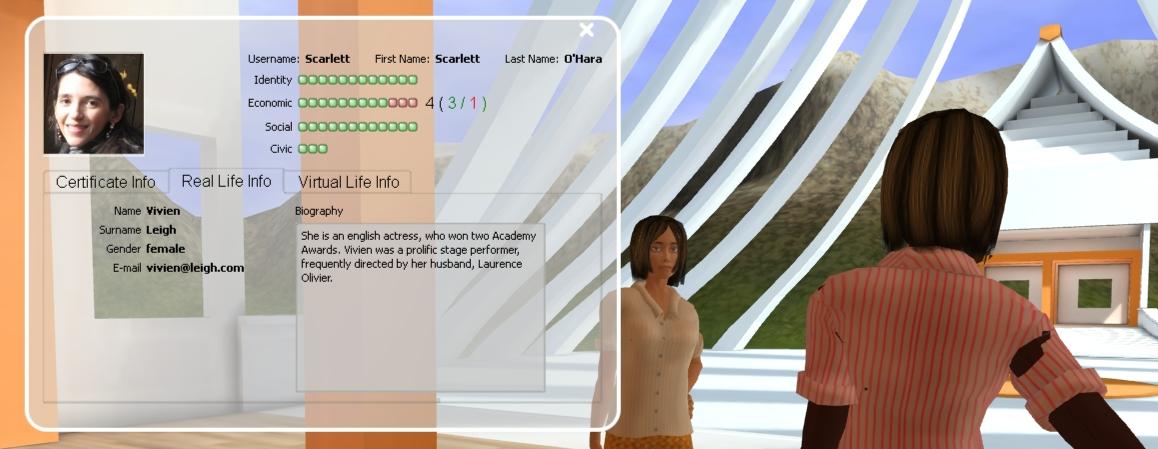

This can be illustrated by the avatar identity card in VirtualLife. Each avatar has an ID card, which contains information about the avatar’s virtual and real-life identities. The ID card includes simple indicators of trust. A red (entrusted) bar means that the avatar is a guest and has not proved his or her identity; a yellow (weakly trusted) bar indicates that the avatar has an identity, but it has not been verified by any certification authority; and a green (trusted) bar denotes that the avatar’s identity has been verified by a certification authority. Furthermore, each avatar has an economic, social, and civic reputation, whose indicators are handled by a sophisticated reputation system that depends on the avatar’s behaviour. Thus energy rules are implemented by hard constraints.

- Professional rules, etc. Other kinds of VirtualLife rules include moral rules, professional rules, user community rules, etc. For example, in VirtualLife, the users can engage in a trusted community called a Virtual Nation, in which particular rules apply.

The architecture of VirtualLife

The VirtualLife project aimed to develop a prototype of a virtual world platform. The main pillars are:

- Strong identity

- Decentralized peer-to-peer (P2P) network architecture

- Interactivity and scripting

- Legal and social cooperation framework.

A motivating example of identity verification and trusted service provision is business transactions, where parties need to identify each other to enter an agreement. To prove the concept, currently VirtualLife is targeted at scenarios focused on learning support, such as (1) a university virtual campus and (2) simulations of human and environmental interactions in costly or dangerous situations.

Strong identity. Unlike most other virtual world platforms, VirtualLife requires that the person behind each avatar be real; VirtualLife forbids avatar principals from using pseudonyms. Thus, VirtualLife’s identity system requires the user behind an avatar to prove that he or she really is who he or she claims to be. The requirement that an avatar’s principal be responsible for actions in the virtual world to the same extent as he or she is in the real world is the basis for building any legal framework in the VirtualLife platform. The avatar’s principal needs to be traceable with a customizable and transparent level of trust. This level can be enforced directly within the final platform, according to the rules one wants to impose on its participants. Such rules are either specific to the implemented business logic, or can be dynamically disclosed and enhanced in specific moments during VirtualLife usage.

For this reason, behind any identity in VirtualLife are X.509 compliant certificates. Such a certificate can be issued by a certification authority (CA), either an externally trusted one or a dedicated one. The platform provides, for bootstrapping purposes, an internal CA. Its certification policy is set at installation time according to the company policy.

Together with an X.509 certificate goes a keypair. The private part of this keypair is usually protected by some means (related once again to the general policy the platform provider wants to adopt). VirtualLife, by default, protects the private part of the keypair with a password. The password is exclusively used to unlock the access to the locally stored keypair and is not used for authentication. (This is the same approach used by openssh when using keybased authentication.)

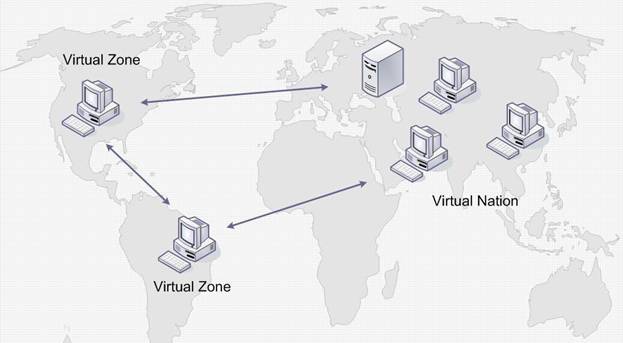

Decentralized peer-to-peer architecture. First of all, VirtualLife can inherently be run on separate servers (even servers located at different physical locations). This means that the architecture of VirtualLife — unlike the architectures of other similar virtual worlds today — allows for a configuration in which no single provider/company owns and rules the entire virtual world. When, within VirtualLife, Zones (i.e., world subparts) federate with a specific Virtual Nation (see details below), they implicitly accept and abide by its rules. They make use of Nation services, and can customize part of the laws to some extent, depending on the original Constitution and law in the Nation. Every VirtualLife avatar is able to verify the current set of laws that rule the specific part of the world he or she is logged in to. Changes in the laws are allowed through a democratic e-voting process.

A Virtual Nation is a set of VirtualLife users sharing the same purpose and values. Within each Virtual Nation are virtual entities based on such real-world concepts as “constitution,” “government,” “register office,” etc. Legal values such as “avatar integrity,” “honour,” “freedom of thought,” “freedom of association,” “sanctity of property,” etc. are implicitly or expressly provided for in the code of conduct within the Virtual Constitution that governs each Virtual Nation.

A Virtual Nation is defined by:

- The list of Virtual Zones belonging to it;

- The allowed avatars (virtual citizens), authorised by the Virtual Nation;

- A constitution (that will be mapped onto a set of technologically implemented laws).

Legal and social cooperation frameworks. Within VirtualLife, people primarily cooperate directly in the 3D world, where avatars can assemble, arrange, prepare, or edit their surroundings. Other mechanisms for social interaction and cooperation within VirtualLife include:

- Public text chat

- Private encrypted text chat

- Voice over IP (VOIP)

- Reputation and evaluation mechanisms

- Friendship relationship

- Contracts

- Online dispute resolution

- E-voting.

Interactivity and scripting. The Lua language and the Scripting Engine allow interactivity and programming of complex behaviour within VirtualLife. Scripting has been targeted toward programmers, privileging power over ease-of-use. Scripting is on both server side (to define the behaviour of interactive entities and to implement some “virtual laws”) and client side (to personalize the graphical user interface and to create building tools).

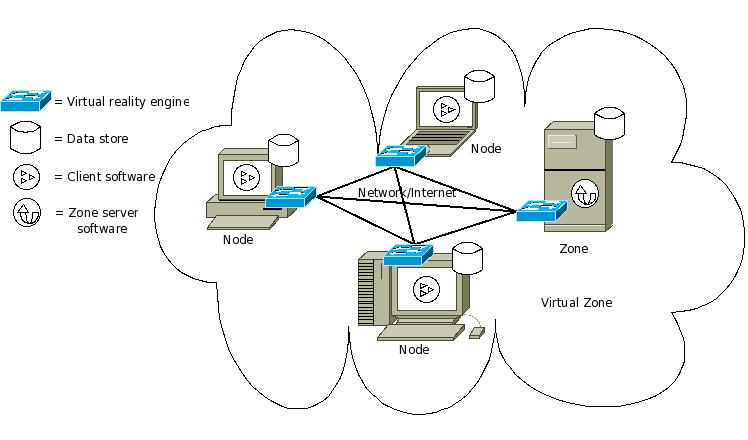

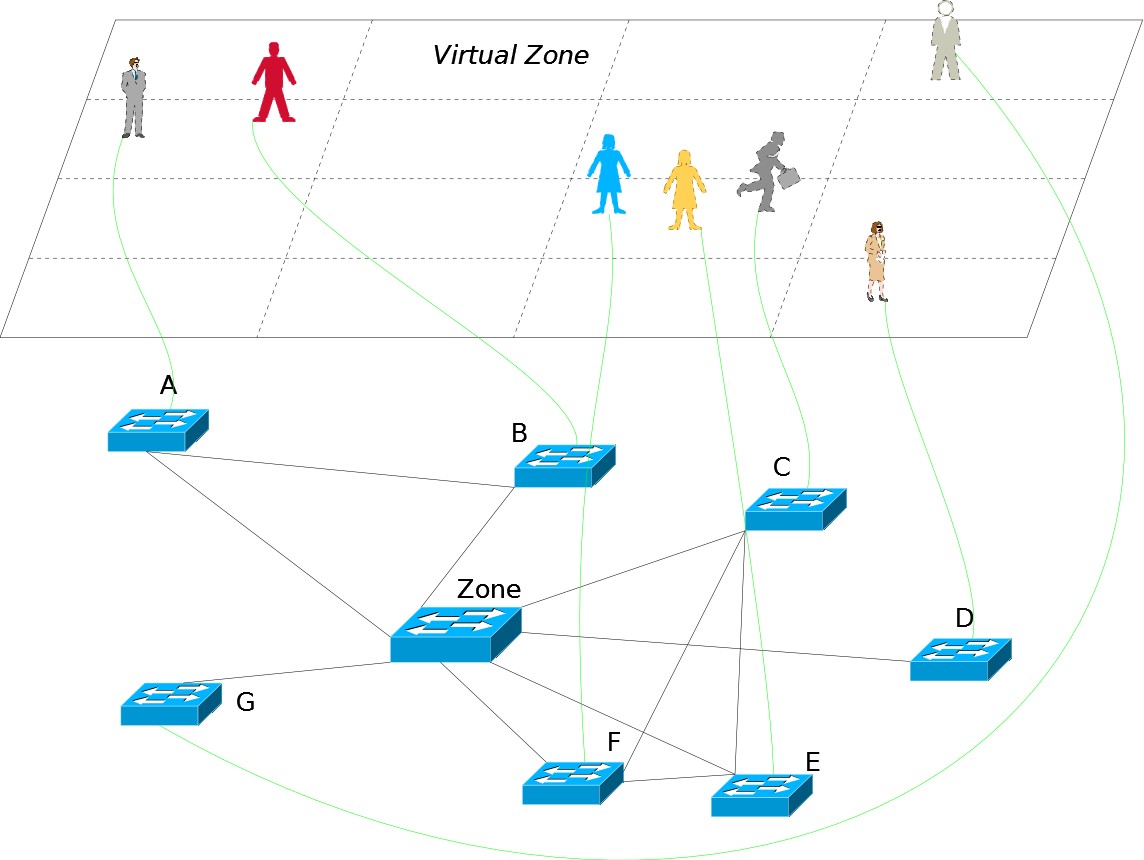

Nodes, Virtual Zones, and Virtual Nations. Each virtual world in VirtualLife consists of a peer-to-peer network with nodes connected using a secure protocol. Control in each virtual world subpart (referred to as a “Virtual Zone” or, simply, a “Zone”) is managed by a Zone server (Z-server). A collection of Zones forms a Virtual Nation, consisting of a network of Virtual Zone servers. The peer-based connection model of a Virtual Zone is depicted below:

Virtual Zone server. Unlike in traditional client-server approaches, there is no centralized point of truth regarding the state of entities in the P2P virtual environment. The truth is maintained in a distributed fashion, where a single node on the network is the authority for a particular entity. The authority node is the only node that sends “update” messages to the rest of the peers, where the latter resolve their internal representations with the truth obtained from the authority.

Innovative features in the virtual legal framework

Today, most virtual worlds try to prevent conflicts through rules of conduct contained in end-user license agreements (EULAs) and terms of service. But this regulation is not enough. The existence of rules does not prevent a user from engaging in bad behaviour towards another user. When a user feels that an injustice has occurred, the only way the user can seek justice is to report the abuse to the virtual world’s creators, who can decide to ban or punish the offender. In some cases, the creators invest in specific techniques to keep the virtual world “under surveillance,” e.g., the peacekeepers in Active Worlds. VirtualLife takes a different approach to regulation.

VirtualLife’s legal framework is a three-tier system:

- A “Supreme Constitution”;

- A “Virtual Nation Constitution” (e.g., Constitution VN1, … , Constitution VNn);

- A set of diverse sample contracts.

The Supreme Constitution expresses the fundamental principles of VirtualLife that every user has to adhere to. Additionally, the Supreme Constitution sets out the basic organisational rules according to which the laws of a Virtual Nation, the second tier of the framework, are formed.

A Virtual Nation Constitution contains special and more detailed provisions as regards, for example, the protection of copyrighted objects used in that Virtual Nation, or the authentication procedure required to become a member of that Nation. The Supreme Constitution and each Virtual Nation Constitution are ordinary contracts, implemented by way of click-wrap agreements.

Contracts. The third tier of the VirtualLife legal framework consists of a variety of sample contracts that parties may use to formalise the terms of their transactions, though parties remain free to use their own contractual terms. Currently, two pre-filled contractual templates are being developed, that will be offered to both the Professors’ group and the Students’ group in VirtualLife. Additional clauses of these model contracts concern such issues as the role of an auditor, the VirtualLife reputation system, and dispute resolution.

Effecting the Virtual Constitution at the level of contract law contributes to law enforcement. The EULA represents soft constraints on VirtualLife users’ behaviour through the users’ avatars. Apart from this, a user of VirtualLife software is not ruled exclusively by the previously mentioned sources of law in VirtualLife; the user is also governed by his or her real-world national law — VirtualLife users cannot escape from the law of the material world.

Virtual laws. Within a Virtual Nation, laws are also defined via a dedicated constrained language that is able to translate concepts related to copyrights and rights of use over in-world objects, into the terms of the underlying virtual reality engine permissions system. These laws are defined in terms of permissions respecting in-world entities, and rights-to-change those permissions, that each avatar category grants to other avatar categories. For example, different values and rules are covered by “NoCopy,” “CopyRight,” and “CopyLeft” Nations. Permission language tables serve to implement particular rights.

Related work

Respecting legal issues, the concept of electronic agent has received much scholarly attention; see, e.g., Artificial Intelligence and Law, vol. 12, no. 1-2 (2004). Respecting issues related to the construction of virtual worlds, such as operational implementation, a recent issue of the same journal was devoted to software agents and normativity; see Artificial Intelligence and Law, vol. 16, no. 1 (2008). Anton Bogdanovych (2007) has developed the concept of “virtual institutions” (VIs), defined as “3D virtual worlds with normative regulation of interactions.” VIs incorporate the strengths of normative multiagent systems, particularly “electronic institutions”; see, e.g., Marc Esteva (2003).

Conclusions

Virtual worlds are part of the real world. However, legal and security features of virtual worlds need to be improved in order to guarantee safe and reliable virtual infrastructures.

In virtual worlds, we face the challenge of building a bridge between reality as it “ought-to-be” and reality “as it is.” Here, software engineers identify the rules for virtual worlds, and implement them in computer code. A part of these rules can be explicitly represented — this part corresponds to the “strong” interpretation of the term “normative multiagent system” (see Boella et al. (2009)). A part cannot be represented explicitly, however. Rules of this kind are formulated explicitly in the system specification, namely, in the EULA text — consistent with the “weak” interpretation of “normative multiagent system” (Boella et al.).

A complete implementation of legal rules in software is infeasible. Whereas technical rules allow little space for interpretation — and therefore can be implemented — legal rules allow too much space for interpretation. Moreover, the limits of this space can only be interpreted by lawyers and judges — not programmers untrained in law. Therefore engineers developing legal information systems cope with the following problems:

- Abstractness of norms. Norms are formulated (on purpose) in very abstract terms.

- Open texture. See H.L.A. Hart’s example of “Vehicles are forbidden in the park.”

- Teleology. The purpose of a legal norm usually can be achieved in a variety of ways.

- Legal interpretation methods. The meaning of a legal text cannot be extracted from the text alone. Apart from the grammatical interpretation, other methods can be invoked, such as systemic and teleological interpretation.

In the VirtualLife system, these challenges have been addressed through an architecture in which legal norms and technical constraints complement each other. This architecture points to the development of virtual worlds manifesting new levels of reliability and security.

Vytautas Čyras is associate professor at the Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics of Vilnius University (VU), Lithuania, EU. He teaches computer science and artificial intelligence. He received a Master’s degree in computer science from VU (1979) and a Ph.D. from Lomonosov Moscow State University (1985) with a doctoral dissertation entitled “Synthesis of Loop Programs over Multidimensional Data Structures.” In 2007, he earned a Master’s degree in law from VU. He is interested in legal informatics and legal theory.

Vytautas Čyras is associate professor at the Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics of Vilnius University (VU), Lithuania, EU. He teaches computer science and artificial intelligence. He received a Master’s degree in computer science from VU (1979) and a Ph.D. from Lomonosov Moscow State University (1985) with a doctoral dissertation entitled “Synthesis of Loop Programs over Multidimensional Data Structures.” In 2007, he earned a Master’s degree in law from VU. He is interested in legal informatics and legal theory.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor in chief is Robert Richards.

Within the field of legal informatics, discussions often focus on the technical and methodological questions of access to legal information. The topics can range from classification of legal documents to conceptual retrieval methods and Automatic Detection of Argumentation in Legal Cases. Researchers and businesses try to increase both precision and recall in order to improve search results for lawyers, while public administrations open up the process of legislating for the benefit of democracy and openness. Where are, however, the benefits for laypersons not familiar with retrieving legal information? Does clustering of legal documents, for example, yield a legal text any more understandable for a citizen?

To answer these questions, I would like to go back to the beginning, the purpose of law. Unfortunately for us lawyers, law is not created for us, but to serve as the oil that keeps society running smoothly. One can imagine two scenarios to apply the oil: If the motor has not been taken care of sufficiently, some extra greasy oil might be necessary to get it running again (i.e. if all amicable solutions are exhausted, some sort of dispute resolution is required), this would be the retroactive approach. The other possible application is to add enough oil during driving, so the engine will continue running smoothly without any additional boost, in other words trying to avoid disputes, this would be the proactive line of thinking.

How can proactive law work for the citizens? The basic assumption would be that in order to avoid disputes, one has to be aware of possible legal risks and how to prevent them. In line with the position of the European Union, we can further assume that the assessment and evaluation of risks requires relevant information about the legal facts at hand. It is only possible for a citizen to reach a decision regarding, for example, social benefits or certain rights as an employee, if she or he is aware of the various legal rights and obligations as well as possible legal outcomes.

Having stipulated that legal information is the core requirement for being able to exercise one’s rights as a citizen, the next questions would include which type of information is actually necessary, who should be responsible to communicating it and how it should be provided. These questions I would like to discuss below. That is, we will talk about why, what, who and how.

Why?

Before we move on to the main theme at hand on access to legal information, I would like to highlight a few more things about the why. As already mentioned, and as many legal philosophers have noted, law is the clockwork that makes society click. The principle Ignorantia juris neminem excusat (Ignorance of the law is no excuse) is commonly accepted as one of the foundations of modern civilization. But how would we define ignorance in today’s world? What if a citizen has troubles finding the necessary information despite endless efforts? What if she or he, after finding the relevant information, is not able to understand it? Does this mean she or he is still ignorant?

Public access to legal information is also a question of democracy, because citizens’ insight into politics, governmental work and the lawmaking process is a necessary prerequisite for public trust in the legislative body.

“In shifting from infrastructure to integration and then to transformation, a more holistic framework of connected governance is required. Such a framework recognizes the networking presence of e-government as both an internal driver of transformation within the public sector and an external driver of societal learning and collective adaptation for the jurisdiction as a whole.” (UN e-Government Survey 2008)

In this spirit, governments should consider the management of knowledge an increasing importance. “The essence of knowledge management (KM) is to provide strategies to get the right knowledge to the right people at the right time and in the right format.” (UN e-Government Survey 2008) What, then, is the right knowledge?

What?

The term legal information is as obvious as the word law. It is both apparent and imprecise, and yet we use it rather often. Several scholars have tried to define legal information and legal knowledge, inter alia, Peter Wahlgren in 1992, Erich Schweighofer in 1999, and Robert Richards in 2009.

If we consider the term from a layperson’s perspective, one could define it as the data, the facts and figures, that are necessary to solve an issue–one that cannot be handled amicably–between two persons (either legal or physical). In order for a layperson to be able to utilize legal information she or he has to be able to access, read, understand and apply the information.

The accessing element is one of the tasks that legal information institutes fulfill so elegantly. The term “reading” is here to be understood as information that can be grasped either with one’s eyes or ears. The complexity begins when it comes to understanding and applying the information. A layperson might have difficulties understanding and applying the Act on income tax even though the law is accessible and readable.

Is this information then still legal information if we assume that the word “information” means that somebody can receive certain signs and data and use this data meaningful in order to increase her or his knowledge? “Knowledge and information […] influence in a reciprocal way. Information modifies knowledge and knowledge guides potential use of information.” (Schweighofer)

If a layperson does not understand the information provided by official sources, she or he might refer to other information sources, for example by utilizing a Google search. In this case, the question arises how reliable the retrieved information is, however comprehensible. A high ranking in Google search does not automatically relate to high quality of the information even though this might be a common misconception, especially for laypersons not trained in source criticism. Here the importance of providing citizens with some basic and comprehensible information becomes apparent.

This comprehensible information might include more than plain text-based legislation and court decisions. Of interest for the layperson (both in business-consumer as well as government-citizen situations) can furthermore be, inter alia,

- additional requirements according to terms and conditions or specific procedural rules in public administrations

- possible legal outcomes and necessary facts that lead to them

- estimated time of delivery of the product or the decision

- creditability of the business, including the amount of pending cases before the courts or complaints before the consumer protection authorities.

For a citizen it might also be very significant to know how she or he could behave differently in order to reach a desired result. Typically, citizens are only provided with the information as to how the legal situation is, but not what they could do to improve it, unless they contact a lawyer.

Commonly all these types of data already exist, if maybe not in one location. The most – technically – accessible information are traditional legal sources, such as legislation and case-law. Again, here the question mainly focuses on how to provide and utilize the existing information in a fashion understandable to the user.

“Like any other content transmitted through a communication system, primary legal sources can be rendered more or less understandable, locatable, and hence effective by structuring and presenting them differently for different audiences. And secondary sources must of course be constructed for a particular market, audience, or level of understanding. “(Tom Bruce)

Who should then be responsible for structuring, presenting and rendering it understandable, especially in the light of source criticism and trust?

Who?

Ignorantia juris neminem excusat presupposes that the legal information provided is correct and of high quality. Who can guarantee such a quality? The state, private entities, research facilities, non-governmental organizations or citizens? My answer would be that all could contribute their part of the game.

One should, however, keep in mind, that user-friendliness is not the same as trustworthiness, which leads to the question of how to ensure that citizens are supplied with the right answers? In a world where even governments do not always take responsibility for the correctness of the provided information, such as in the case of online publications for law gazettes, the question remains who, or what entity, should be held liable for the accuracy of its services. But even if a public authority would sustain accountability, to what extent could that influence an already reached legal decision?

The answer of who should provide a certain legal information service could also depend on who the target group of the information is.

“The legal information market is really no longer conceivable as bipolar – it can no longer be seen as a question of lawyers on the one hand versus a largely legally ignorant everyone else on the other. […] Internet-based legal information systems are used by many cases and conditions of people for many different reasons. […] Probably the most interesting group [are] non-lawyer professionals. These are people whose interest in law is vital, ongoing, and professional rather than either being casual and hobby-like or sporadic and trauma-driven. […] Such new and diverse audiences require new and diverse legal information architectures. They will want specialized collections of law of particular relevance to them. They will want those collections organized and presented in ways that reflect their profession or their situation, in ways that collections organized according to the legal abstractions and legal terms in use by lawyers do not. They are concerned with situations and fact-patterns rather than theories, doctrines, and concepts. They are, in short, a very intelligent and exciting type of lay users, and a potentially enormous audience. ‘(Tom Bruce)

Non-lawyer professionals probably constitute a large market for businesses that can tailor their services to a specific group and therefore render them profitable, as the services are considered of value for these professionals.

Traditional laypersons, however, typically do not represent a large market power simply because they will not always be willing to pay for services of this kind. This leaves them to the hands of other stakeholders such as public administrations, research institutes, non-governmental organizations and private initiatives. As already mentioned, conventionally the raw data is supplied by public administrations. The question, then, is how to deliver it to the end-user.

How?

The Austrian civil code knows two concepts regarding fulfilling one’s part of the contract, Holschuld and Bringschuld. Holschuld means a debt to be collected from the debtor at his residence. Bringschuld constitutes an obligation to be performed at creditor’s habitual residence. In today’s terminology, one could compare Holschuld with pull technology and Bringschuld with push technology. In other words, should the citizens pick up the relevant legal information or should the government actively deliver it at people’s doorsteps, so to speak?

In the offline paper world, the only way to reach a citizen was to send a letter to her or his house. Obviously, information technology offers many more possibilities when it comes to communicating with citizens, either via a computer or even a mobile phone, taking privacy concerns into consideration.

Several e-government and initiatives (video feed from European Parliament sessions and EU’s channel at Youtube) increase the public participation and insight into politics. While these programs are an important contribution to democracy, they typically do not facilitate daily encounters with legal issues of employment, family, consumer, taxes or housing, or provide citizens with the necessary information to do so.

In this respect, technologies enabling interactivity and re-use of public information are of greater importance, the latter also being a strategic concern of the European Union. In particular, semantic technology offers solutions for transforming raw data into comprehensible information for citizens. Here, practical examples that utilize at least part of this technology can also be found within e-government projects as well as in private initiatives.

The next step would be law being built into the code already. Intelligent agents negotiate the most advantageous terms and conditions for their owner, cars prevent being switched on if the driver exceeds the permitted alcohol level (Ignition interlock device) and music songs do not play unless your device is authorized (iTunes).

So, from a technological point of view, anything from presenting legal information on a website to implementing law directly into the end device is possible. In practice, though, most governments are content with providing textual legal information, at best in a structured format so it can be re-used easier. The technical implementation of more advanced functions is often left to other market players and businesses.

There are two initiatives in this respect that are worth mentioning, one being a true private project in Sweden and the other one being provided by the Austrian government.

Lagen.nu (law now) has been around for some time now as a private initiative offering free access to Swedish legislation and case law. Recently the site was extended by adding commentaries to specific statutes, which should enable laypersons to understand certain legislation. The site includes explanations for certain terminology and particular comments are also categorized and include links to other laws and cases.

The other example, HELP, a service provided by the Austrian Government Agency, structures and presents legal information depending on the factual situation, e.g. it contains categories such as employment, housing, education, finances, family and social services. The relevant legal requirements are then explained in plain text and the responsible authority is listed and linked to. In some cases the necessary procedure can even be initiated through the web site.

Both projects are fine examples of the possible transformation of legal information from pull to push technology. They are not quite there yet, though.

The answer

The question we are faced with now is not so much how or which technique would be the best, but rather in which situation a citizen might need certain legal information. Somebody trying to purchase a book via a web site might need information at that moment, and either as a warning text or a check list or its intelligent agent, the purchaser might go to another web site that has better ratings and more favorable legal terms and conditions and no pending law suits. In some other cases, the citizen might need certain information in a specific situation right at the spot. For example, while filling out a form she or he might want to know what would be most favorable choice, rather than simply the type of personal data required for the form. Depending on the situation, different approaches might be more valuable than others.

The larger issue at hand is where the information is retrieved and who is the provider of the information. In other words, trust is an important factor, particularly trust of the information provider. As previously stated, legal information is not usually provided by public bodies but instead is rerouted through various other entities, such as businesses, organizations and individual efforts. This increases the importance of source criticism even more.

In many cases citizens will use general portals such as Google or Wikipedia to search for information, rather than going directly to the source, most often because citizens are not aware of the services offered. This underlines the importance for legal information providers to co-operate with other communication channels in order to increase their visibility.

The necessary legal information is out there, it just remains to be seen if and how it reaches the citizens. Or to put it in other words: The prophet still has to come to the mountain, but in time, with the increasing use of technology, maybe the mountain will come a bit closer.

Christine Kirchberger has been a junior lecturer at the Swedish Law and Informatics Research Institute, Stockholm University) since 2001. Besides teaching law and IT she is currently writing her PhD thesis on Legal information as a tool where she focuses on legal information retrieval, the concept of legal information within the framework of the doctrine of legal sources and also takes a look at the information-seeking behavior of lawyers.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt.

On the 30th and 31st of October 2008, the 9th International Conference on “Law via the Internet”met in Florence, Italy. The Conference was organized by the Institute of Legal Information Theory and Techniques of the Italian National Research Council (ITTIG-CNR), acting as a member of the Legal Information Institutes network (LIIs). About 300 participants, from 39 countries and five continents, attended the conference. The conference had previously been held in Montreal, Sydney, Paris, and Vanuatu.

On the 30th and 31st of October 2008, the 9th International Conference on “Law via the Internet”met in Florence, Italy. The Conference was organized by the Institute of Legal Information Theory and Techniques of the Italian National Research Council (ITTIG-CNR), acting as a member of the Legal Information Institutes network (LIIs). About 300 participants, from 39 countries and five continents, attended the conference. The conference had previously been held in Montreal, Sydney, Paris, and Vanuatu.

The conference was a special event for ITTIG, which is one of the institutions where legal informatics started in Europe, and which has supported free access to law without interruption since its origin. It was a challenge and privilege for ITTIG to host experts from all over the world as they discussed crucial emerging problems related to new technologies and law.

Despite having dedicated special sessions to wine tasting in the nearby hills (!), the Conference mainly focused on digital legal information, analyzing it in the light of the idea of freedom of access to legal information, and discussing the technological progress that is shaping such access. Within this interaction of technological progress and law, free access to information is only the first step — but it is a fundamental one.

Increased use of digital information in the field of law has played an important role in developing methodologies for both data creation and access. Participants at the conference agreed that complete, reliable legal data is essential for access to law, and that free access to law is a fundamental right, enabling citizens to exercise their rights in a conscious and effective way. In this context, the use of new technologies becomes an essential tool of democracy for the citizens of an e-society.

The contributions of legal experts from all over the world reflected this crucial need for free access to law. Conference participants analysed both barriers to free access, and the techniques that might overcome those barriers. Session topics included:

- The Right to Access Legal Information

- Free Access to Law: Information Systems and Institutions in Europe

- A Legal Framework for Open Access to Legal Information

- The Global Scope of Free Access to Law

- Information and Communication Technologies and the Quality of Legal Information

- Strategic Solutions and Sustainability Models for the Diffusion and Sharing of Legal Knowledge

In general, discussions at the conference covered four main points. The first is that official free access to law is not enough. Full free access requires a range of different providers and competitive republishing by third parties, which in turn requires an anti-monopoly policy on the part of the creator of legal information. Each provider will offer different types of services, tailored to various public needs. This means that institutions providing legal data sources have a public duty to offer a copy of their output — their judgments and legislation in the most authoritative form — to anyone who wishes to publish it, whether that publication is for free or for fee.

Second, countries must find a balance between the potential for commercial exploitation of information and the needs of the public. This is particularly relevant to open access to publicly funded research.

The third point concerns effective access to, and re-usability of, legal information. Effective access requires that most governments promote the use of technologies that improve access to law, abandoning past approaches such as technical restrictions on the reuse of legal information. It is important that governments not only allow, but also help others to reproduce and re-use their legal materials, continually removing any impediments to re-publication.

Finally, international cooperation is essential to providing free access to law. One week before the Florence event, the LII community participated in a meeting of experts organised by the Hague Conference on Private International Law’s Permanent Bureau; a meeting entitled “Global Co-operation on the Provision of On-line Legal Information.” Among other things, participants discussed how free, on-line resources can contribute to resolving trans-border disputes. At this meeting, a general consensus was reached on the need for countries to preserve their legal materials in order to make them available. The consensus was that governments should:

- give access to historical legal material

- provide translations in other languages

- develop multi-lingual access functionalities

- use open standards and metadata for primary materials

All these points were confirmed at the Florence Conference.

The key issue that emerged from the Conference is that the marketplace has changed and we need to find new models to distribute legal information, as well as create equal market opportunities for legal providers. In this context, legal information is considered to be an absolute public good on which everyone should be free to build.

Many speakers at the Conference also tackled multilingualism in the law domain, highlighting the need for semantic tools, such as lexicons and ontologies, that will enhance uniformity of legal language without losing national traditions. The challenge to legal information systems worldwide lies in providing transparent access to the multilingual information contained in distributed archives and, in particular, allowing users express requests in their preferred language and to obtain meaningful results in that language. Cross-language information retrieval (CLIR) systems can greatly contribute to open access to law, facilitating discovery and interpretation of legal information across different languages and legal orders, thus enabling people to share legal knowledge in a world that is becoming more interconnected every day.

From the technical point of view, the Conference underlined the paramount importance of adopting open standards. Improving the quality of access to legal information requires interoperability among legal information systems across national boundaries. A common, open standard used to identify sources of law on the international level is an essential prerequisite for interoperability .

In order to reach this goal, countries need to adopt a unique identifier for legal information materials. Interest groups within several countries have already expressed their intention to adopt a shared solution based on URI (Universal Resource Identifier) techniques. Especially among European Union Member States, the need for a unique identifier, based on open standards and providing advanced modalities of document hyper-linking, has been expressed in several conferences by representatives of the Office for Official Publications of the European Communities (OPOCE).

Similar concerns about promoting interoperability among national and European information systems have been aired by international groups. The Permanent Bureau of the Hague Conference on Private International Law is considering a resolution that would encourage member states to “adopt neutral methods of citation of their legal materials, including methods that are medium-neutral, provider-neutral and internationally consistent.” ITTIG is particularly involved in this issue, which is currently running in parellel with the pan-European Metalex/CEN initiative to define standards for sources of European law.

The wide discussions raised during the Conference are collected in a volume of Proceedings published in April 2009 by European Press Academic Publishing – EPAP.

— E. Francesconi ,G. Peruginelli

Ginevra Peruginelli

Ginevra Peruginelli

Ginevra has a degree in law from the University of Florence, a MA/MSc Diploma in Information Science awarded by the University of Northumbria, Newcastle, UK and a Ph.D. in Telematics and Information Society from the University of Florence. Currently she is a researcher at the Institute of Legal Theory and Techniques of the Italian National Research Council (ITTIG-CNR). In 2003, she was admitted to Bar of the Court of Florence as a lawyer. She carries out her research activities in various sectors, such as standards to represent data and metadata in the legal environment; law and legal language documentation; and open access for law.

Enrico Francesconi

Enrico Francesconi

Enrico is a researcher at ITTIG-CNR. His main activities include knowledge representation and ontology learning, legal standards, artificial intelligence techniques for legal document classification and knowledge extraction. He is a member of the Italian and European working groups establishing XML and URI standards for legislation. He has been involved in various projects within the framework programs of DG Information Society & Media of the European Commission and for the Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt