In this article, I reflect on the legal frameworks that affect virtual worlds. In particular, I focus on the use of non-game three-dimensional online virtual worlds such as Second Life, for purposes of education and training. These worlds are also known as “serious” games. Pictured below is an example of such a “serious” game: a possible learning support scenario — interacting with a complex 3D geometric object, in the context of a geometry lesson within a virtual world.

The European Union Information and Communication Technologies Seventh Framework Programme, FP7 ICT, has funded a VirtualLife consortium of ten partners that plans to create a secure and legally ruled virtual world platform. The legal framework they are constructing includes a novel, editable, and enforceable Virtual Constitution. This article describes the legal framework of VirtualLife, using material from several VirtualLife project deliverables: a presentation and publications, primarily Bogdanov et al. (2009), and Čyras & Lachmayer (2010).

The problem of law enforcement in virtual worlds

The rules of games, such as chess, can be programmed. However, this is not the case for legal rules contained in a code of conduct in a virtual constitution. Moreover, in a code of conduct for a virtual world, we supplement the normal concept of “persons” who are subject to law, with the concept of “avatars” — that is, the virtual persons used to navigate a virtual world. This variety of rules, which applies to avatars, is called “virtual law” (see Raph Koster). A sample “toy” rule, such as “Keep off the grass,” illustrates constraints on avatar conduct, constraints aimed primarily at preventing unwanted behaviour.

Various methods of norm enforcement by computers are being investigated worldwide (see, e.g., Vázquez-Salceda et al. (2008)). Lawrence Lessig‘s Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace (1999, updated in 2005) noted that cyberspace would be controlled — or not — depending upon the architecture, or “code,” of that space.

A general frame of a virtual world

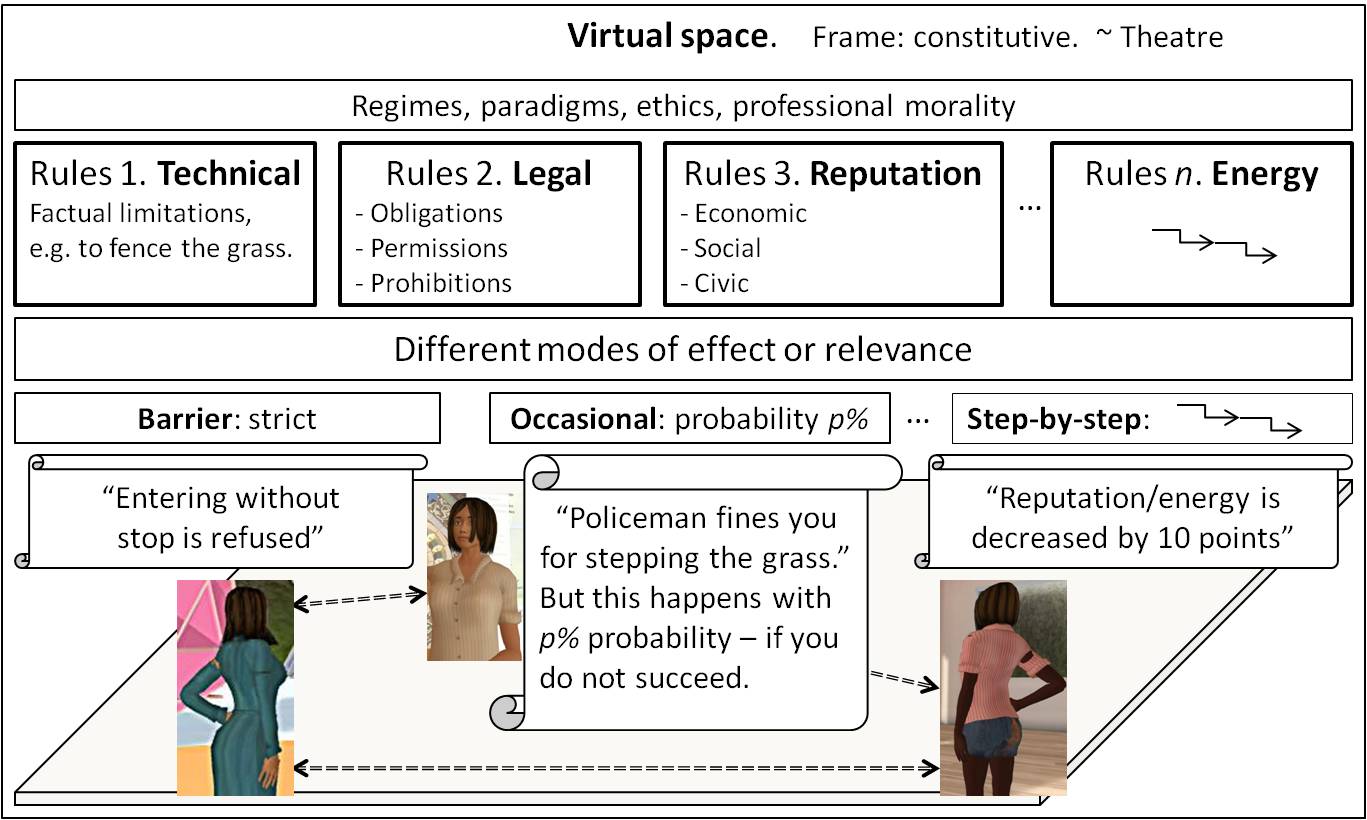

A general sketch of virtual world legal issues, as described by legal scholar Friedrich Lachmayer, is outlined below. It differs from the view of software engineers. Many legal rules in a virtual world are described informally. The entities of major importance are avatar actions and the rules that regulate their behaviour. Here is a conceptualisation of the “theatre” depicting the elements of a virtual world and the principles of construction of its legal framework:

Rules can form different normative systems within a virtual world, as well as a regime, or paradigm, of a virtual world. The rules in a virtual world can have different modes or degrees of effectiveness, such as “barrier,” “occasional,” “step-by-step,” etc. Moreover, these rules can be divided into different classes, such as technical rules, legal rules, reputation rules, energy rules, and professional rules:

- Technical rules establish factual limitations. Real world examples include fencing in a plot of grass, locking a door to forbid entry, and an automatic teller machine’s refusing to dispense money unless a PIN code is provided. Violations of technical rules are impossible: there is no possibility of violating a technical rule unless you break the artifact completely (e.g., by cutting the fence, or breaking down the door). Hence technical rules are strictly enforceable. They are based on natural necessity and can be formalised as: “If P then Q.” They do not have modes or degrees of effectiveness such as “obligatory,” “permitted,” and “forbidden.”

- Legal rules. Their nature is that they can be violated. For example, you can jaywalk, but you risk being sanctioned. These laws are enforced by an authority such as the police, or peacekeepers in a virtual world. Legal rules are not strictly enforceable, and their enforcement may be subject to the so-called “spirit,” or purpose, of the law.

Legal rules are necessary, because it is impossible to implement normative regulation by means of technical rules alone. Consider a norm providing that indecent content is prohibited in the virtual world. Such an abstract norm can hardly be implemented by automatic checking. A naked body should not be automatically treated as indecent content, because it may be a picture of a statue in a virtual museum.

- Energy rules prohibit certain kinds of behaviour. If energy rules are violated, the violator’s “energy points” are decreased. Such sanctions are 100% effective.

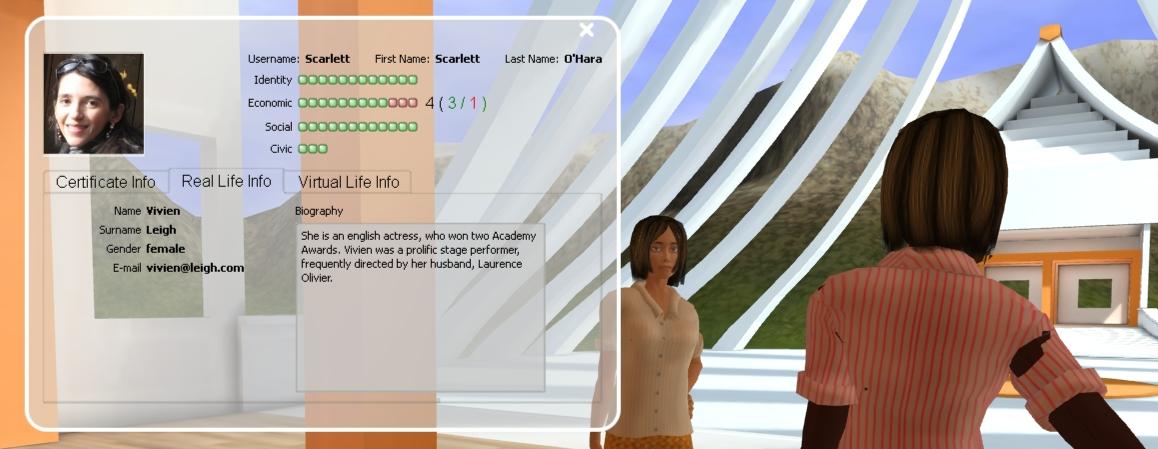

This can be illustrated by the avatar identity card in VirtualLife. Each avatar has an ID card, which contains information about the avatar’s virtual and real-life identities. The ID card includes simple indicators of trust. A red (entrusted) bar means that the avatar is a guest and has not proved his or her identity; a yellow (weakly trusted) bar indicates that the avatar has an identity, but it has not been verified by any certification authority; and a green (trusted) bar denotes that the avatar’s identity has been verified by a certification authority. Furthermore, each avatar has an economic, social, and civic reputation, whose indicators are handled by a sophisticated reputation system that depends on the avatar’s behaviour. Thus energy rules are implemented by hard constraints.

- Professional rules, etc. Other kinds of VirtualLife rules include moral rules, professional rules, user community rules, etc. For example, in VirtualLife, the users can engage in a trusted community called a Virtual Nation, in which particular rules apply.

The architecture of VirtualLife

The VirtualLife project aimed to develop a prototype of a virtual world platform. The main pillars are:

- Strong identity

- Decentralized peer-to-peer (P2P) network architecture

- Interactivity and scripting

- Legal and social cooperation framework.

A motivating example of identity verification and trusted service provision is business transactions, where parties need to identify each other to enter an agreement. To prove the concept, currently VirtualLife is targeted at scenarios focused on learning support, such as (1) a university virtual campus and (2) simulations of human and environmental interactions in costly or dangerous situations.

Strong identity. Unlike most other virtual world platforms, VirtualLife requires that the person behind each avatar be real; VirtualLife forbids avatar principals from using pseudonyms. Thus, VirtualLife’s identity system requires the user behind an avatar to prove that he or she really is who he or she claims to be. The requirement that an avatar’s principal be responsible for actions in the virtual world to the same extent as he or she is in the real world is the basis for building any legal framework in the VirtualLife platform. The avatar’s principal needs to be traceable with a customizable and transparent level of trust. This level can be enforced directly within the final platform, according to the rules one wants to impose on its participants. Such rules are either specific to the implemented business logic, or can be dynamically disclosed and enhanced in specific moments during VirtualLife usage.

For this reason, behind any identity in VirtualLife are X.509 compliant certificates. Such a certificate can be issued by a certification authority (CA), either an externally trusted one or a dedicated one. The platform provides, for bootstrapping purposes, an internal CA. Its certification policy is set at installation time according to the company policy.

Together with an X.509 certificate goes a keypair. The private part of this keypair is usually protected by some means (related once again to the general policy the platform provider wants to adopt). VirtualLife, by default, protects the private part of the keypair with a password. The password is exclusively used to unlock the access to the locally stored keypair and is not used for authentication. (This is the same approach used by openssh when using keybased authentication.)

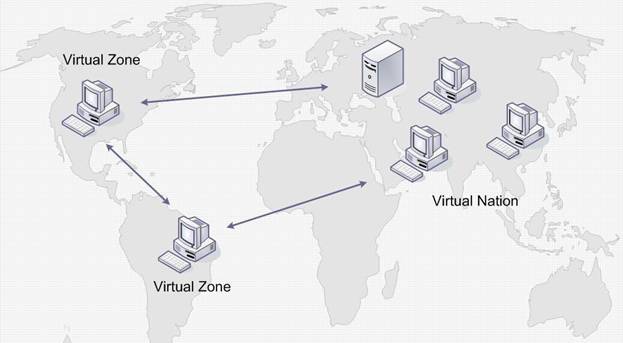

Decentralized peer-to-peer architecture. First of all, VirtualLife can inherently be run on separate servers (even servers located at different physical locations). This means that the architecture of VirtualLife — unlike the architectures of other similar virtual worlds today — allows for a configuration in which no single provider/company owns and rules the entire virtual world. When, within VirtualLife, Zones (i.e., world subparts) federate with a specific Virtual Nation (see details below), they implicitly accept and abide by its rules. They make use of Nation services, and can customize part of the laws to some extent, depending on the original Constitution and law in the Nation. Every VirtualLife avatar is able to verify the current set of laws that rule the specific part of the world he or she is logged in to. Changes in the laws are allowed through a democratic e-voting process.

A Virtual Nation is a set of VirtualLife users sharing the same purpose and values. Within each Virtual Nation are virtual entities based on such real-world concepts as “constitution,” “government,” “register office,” etc. Legal values such as “avatar integrity,” “honour,” “freedom of thought,” “freedom of association,” “sanctity of property,” etc. are implicitly or expressly provided for in the code of conduct within the Virtual Constitution that governs each Virtual Nation.

A Virtual Nation is defined by:

- The list of Virtual Zones belonging to it;

- The allowed avatars (virtual citizens), authorised by the Virtual Nation;

- A constitution (that will be mapped onto a set of technologically implemented laws).

Legal and social cooperation frameworks. Within VirtualLife, people primarily cooperate directly in the 3D world, where avatars can assemble, arrange, prepare, or edit their surroundings. Other mechanisms for social interaction and cooperation within VirtualLife include:

- Public text chat

- Private encrypted text chat

- Voice over IP (VOIP)

- Reputation and evaluation mechanisms

- Friendship relationship

- Contracts

- Online dispute resolution

- E-voting.

Interactivity and scripting. The Lua language and the Scripting Engine allow interactivity and programming of complex behaviour within VirtualLife. Scripting has been targeted toward programmers, privileging power over ease-of-use. Scripting is on both server side (to define the behaviour of interactive entities and to implement some “virtual laws”) and client side (to personalize the graphical user interface and to create building tools).

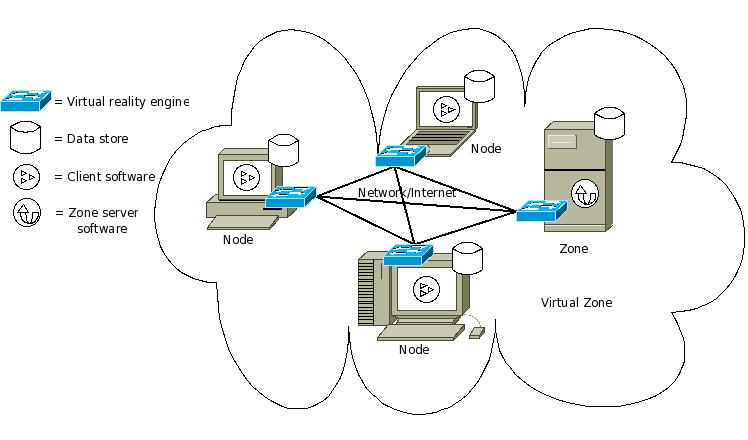

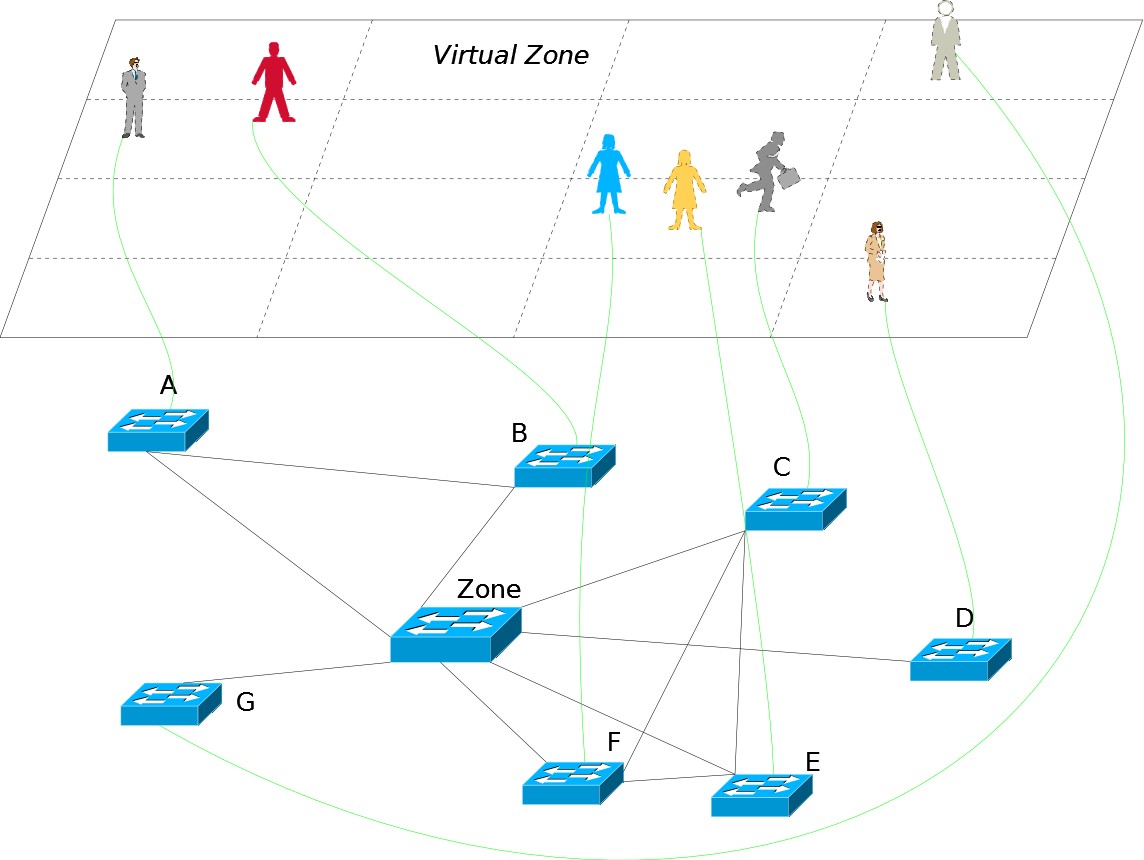

Nodes, Virtual Zones, and Virtual Nations. Each virtual world in VirtualLife consists of a peer-to-peer network with nodes connected using a secure protocol. Control in each virtual world subpart (referred to as a “Virtual Zone” or, simply, a “Zone”) is managed by a Zone server (Z-server). A collection of Zones forms a Virtual Nation, consisting of a network of Virtual Zone servers. The peer-based connection model of a Virtual Zone is depicted below:

Virtual Zone server. Unlike in traditional client-server approaches, there is no centralized point of truth regarding the state of entities in the P2P virtual environment. The truth is maintained in a distributed fashion, where a single node on the network is the authority for a particular entity. The authority node is the only node that sends “update” messages to the rest of the peers, where the latter resolve their internal representations with the truth obtained from the authority.

Innovative features in the virtual legal framework

Today, most virtual worlds try to prevent conflicts through rules of conduct contained in end-user license agreements (EULAs) and terms of service. But this regulation is not enough. The existence of rules does not prevent a user from engaging in bad behaviour towards another user. When a user feels that an injustice has occurred, the only way the user can seek justice is to report the abuse to the virtual world’s creators, who can decide to ban or punish the offender. In some cases, the creators invest in specific techniques to keep the virtual world “under surveillance,” e.g., the peacekeepers in Active Worlds. VirtualLife takes a different approach to regulation.

VirtualLife’s legal framework is a three-tier system:

- A “Supreme Constitution”;

- A “Virtual Nation Constitution” (e.g., Constitution VN1, … , Constitution VNn);

- A set of diverse sample contracts.

The Supreme Constitution expresses the fundamental principles of VirtualLife that every user has to adhere to. Additionally, the Supreme Constitution sets out the basic organisational rules according to which the laws of a Virtual Nation, the second tier of the framework, are formed.

A Virtual Nation Constitution contains special and more detailed provisions as regards, for example, the protection of copyrighted objects used in that Virtual Nation, or the authentication procedure required to become a member of that Nation. The Supreme Constitution and each Virtual Nation Constitution are ordinary contracts, implemented by way of click-wrap agreements.

Contracts. The third tier of the VirtualLife legal framework consists of a variety of sample contracts that parties may use to formalise the terms of their transactions, though parties remain free to use their own contractual terms. Currently, two pre-filled contractual templates are being developed, that will be offered to both the Professors’ group and the Students’ group in VirtualLife. Additional clauses of these model contracts concern such issues as the role of an auditor, the VirtualLife reputation system, and dispute resolution.

Effecting the Virtual Constitution at the level of contract law contributes to law enforcement. The EULA represents soft constraints on VirtualLife users’ behaviour through the users’ avatars. Apart from this, a user of VirtualLife software is not ruled exclusively by the previously mentioned sources of law in VirtualLife; the user is also governed by his or her real-world national law — VirtualLife users cannot escape from the law of the material world.

Virtual laws. Within a Virtual Nation, laws are also defined via a dedicated constrained language that is able to translate concepts related to copyrights and rights of use over in-world objects, into the terms of the underlying virtual reality engine permissions system. These laws are defined in terms of permissions respecting in-world entities, and rights-to-change those permissions, that each avatar category grants to other avatar categories. For example, different values and rules are covered by “NoCopy,” “CopyRight,” and “CopyLeft” Nations. Permission language tables serve to implement particular rights.

Related work

Respecting legal issues, the concept of electronic agent has received much scholarly attention; see, e.g., Artificial Intelligence and Law, vol. 12, no. 1-2 (2004). Respecting issues related to the construction of virtual worlds, such as operational implementation, a recent issue of the same journal was devoted to software agents and normativity; see Artificial Intelligence and Law, vol. 16, no. 1 (2008). Anton Bogdanovych (2007) has developed the concept of “virtual institutions” (VIs), defined as “3D virtual worlds with normative regulation of interactions.” VIs incorporate the strengths of normative multiagent systems, particularly “electronic institutions”; see, e.g., Marc Esteva (2003).

Conclusions

Virtual worlds are part of the real world. However, legal and security features of virtual worlds need to be improved in order to guarantee safe and reliable virtual infrastructures.

In virtual worlds, we face the challenge of building a bridge between reality as it “ought-to-be” and reality “as it is.” Here, software engineers identify the rules for virtual worlds, and implement them in computer code. A part of these rules can be explicitly represented — this part corresponds to the “strong” interpretation of the term “normative multiagent system” (see Boella et al. (2009)). A part cannot be represented explicitly, however. Rules of this kind are formulated explicitly in the system specification, namely, in the EULA text — consistent with the “weak” interpretation of “normative multiagent system” (Boella et al.).

A complete implementation of legal rules in software is infeasible. Whereas technical rules allow little space for interpretation — and therefore can be implemented — legal rules allow too much space for interpretation. Moreover, the limits of this space can only be interpreted by lawyers and judges — not programmers untrained in law. Therefore engineers developing legal information systems cope with the following problems:

- Abstractness of norms. Norms are formulated (on purpose) in very abstract terms.

- Open texture. See H.L.A. Hart’s example of “Vehicles are forbidden in the park.”

- Teleology. The purpose of a legal norm usually can be achieved in a variety of ways.

- Legal interpretation methods. The meaning of a legal text cannot be extracted from the text alone. Apart from the grammatical interpretation, other methods can be invoked, such as systemic and teleological interpretation.

In the VirtualLife system, these challenges have been addressed through an architecture in which legal norms and technical constraints complement each other. This architecture points to the development of virtual worlds manifesting new levels of reliability and security.

Vytautas Čyras is associate professor at the Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics of Vilnius University (VU), Lithuania, EU. He teaches computer science and artificial intelligence. He received a Master’s degree in computer science from VU (1979) and a Ph.D. from Lomonosov Moscow State University (1985) with a doctoral dissertation entitled “Synthesis of Loop Programs over Multidimensional Data Structures.” In 2007, he earned a Master’s degree in law from VU. He is interested in legal informatics and legal theory.

Vytautas Čyras is associate professor at the Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics of Vilnius University (VU), Lithuania, EU. He teaches computer science and artificial intelligence. He received a Master’s degree in computer science from VU (1979) and a Ph.D. from Lomonosov Moscow State University (1985) with a doctoral dissertation entitled “Synthesis of Loop Programs over Multidimensional Data Structures.” In 2007, he earned a Master’s degree in law from VU. He is interested in legal informatics and legal theory.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor in chief is Robert Richards.