Organizations, memories, and routines

Nowadays, information and knowledge management and retrieval systems are widely used in organizations to support many tasks. These include dealing with information overload, supporting decision-making processes, or providing the members of these organizations with the kind of knowledge and information they require to solve problems.

In particular, knowledge management systems may also be understood as a way to manage organizational memories. These are defined, by J.G. March and H.A. Simon, as “repertories of possible solutions to classes of problems that have been encountered in the past and repertories of components of problem solutions.” Thus, these memories reveal proven mechanisms for problem-solving, and bring organizational needs into focus. In turn, these mechanisms enable organizations to reach their goals and help them make decisions in highly uncertain environments.

Therefore, the ability to store and retrieve these mechanisms and to manage organizational memories is central. It allows organizations to learn from their previous decision-making processes, successes and failures. In effect, in both public and private organizations, successful mechanisms typically become routines, that is, adaptive rules of behavior. With such routines available to them, organizations only need to search for further solutions or new alternatives when they fail to detect stored problem-solving or decision-making routines in their memory. However, routines are not only problem-solving devices. More importantly, they are learning devices to turn inexperienced professionals into experts.

Organizational memories contain expert knowledge that can guide both individual and organizational behavior, thus fostering the essential role of organizations as reliable and stable patterns of events. Moreover, organizations will be able to learn from experience as long as they are capable of managing their own memories.

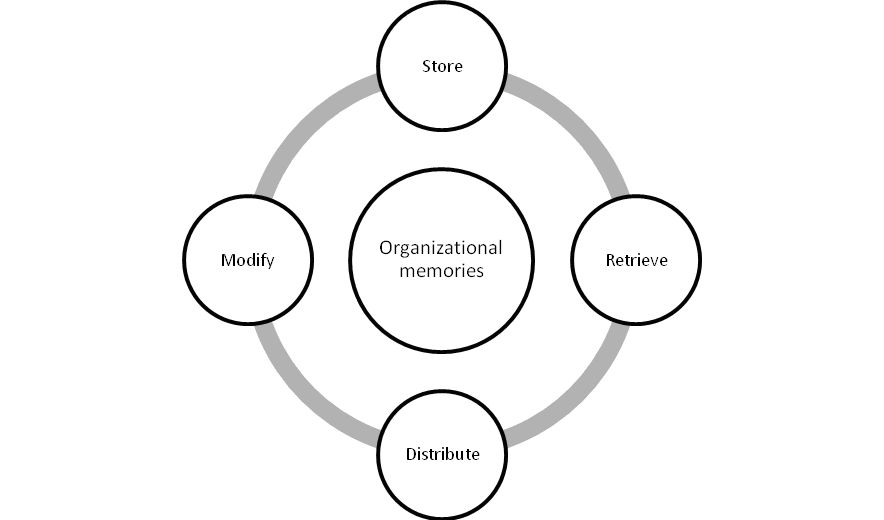

The effectiveness of such knowledge management systems, once implemented, may be measured by an organization’s ability to:

- store ready-made solutions in their memory;

- search and retrieve these solutions (or routines) when problems arise;

- distribute knowledge about these routines among organization members so that they can make adequate decisions; and

- attach new decisions to existing templates, or store them as new ready-made solutions.

Beyond document and case management

In the legal domain, the design and implementation of knowledge management tools has been stimulated by the need to cope with the volume and complexity of knowledge and information produced by current legal organizations.

Applied to judicial administration, these systems typically help with storing, managing, and keeping track of documents used in or related to legal proceedings. Obviously these documents include judicial decisions (and templates and protocols to produce them), but they are specially designed to enable an efficient management of secondary but highly relevant documents issued by the court personnel — such as court orders, decrees, notifications, and transcripts of declarations. These systems help judicial units maintain the information and knowledge that their members need in order to work effectively on every stage of the procedure.

In fact, legal bureaucratic organizations are usually able to maintain and distribute this type of knowledge among their members. The implementation of document and case management systems has been critical to this achievement.

Nevertheless, legal organizations (and organizations in general) produce other types of organizational knowledge than those related to document or case management. Systematic loss of such knowledge, or lack of reuse, may increase uncertainty in inefficient organizational and individual behavior.

In particular, research conducted at the Institute of Law and Technology (IDT) on the integration of junior Spanish judges within their institutional environment shows that, while knowledge management systems implemented in these legal organizations typically deal with document and case management, most of the problems that arise during judicial daily work are of a different nature.

The case of the on-call service in courts

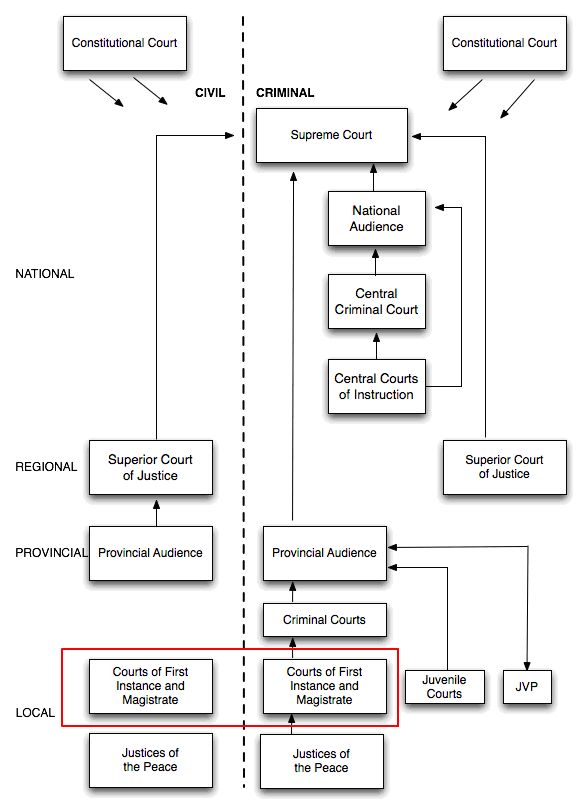

Spain’s legal system is part of the mainstream of European civil law systems, which means that, in contrast to the common law tradition, Spanish judges are specialized civil servants working in a branch of a bigger bureaucratic organization – that is, the State. Ideally, Spanish judges decide cases by applying a corpus of written legal norms that, in principle, should be a complete and coherent repertoire of solutions.

Due to the existence of specialized jurisdictions, the Spanish judicial system is both highly centralized and complex. Courts at the local level, known as Courts of First Instance and Magistrate, are the entry point of the Spanish judicial system. These are the courts where junior judges start their professional career, after an average of seven years of mainly theoretical training.

These judges handle most civil cases, decide upon minor criminal offenses, and start most preliminary criminal proceedings that will be later tried by higher courts. Due to the nature of their responsibilities, the judges appointed to these courts are on-call for 24 hours during an 8-day period, on a rotation basis, to attend any incoming criminal or civil case.

In 2005, I took part in a research project at the IDT that carried out an empirical study of the main professional problems affecting Spanish junior judges in their daily work.

Most of the interviewed judges felt that the on-call service was the main source of both professional problems and stressful situations. During this service, judges faced problems that could be regarded as being of a behavioral, practical nature. Some of those were triggered by both legal and non-legal actors not following established protocols. However, most problems arose from the lack of specific guidelines to deal with situations under time pressure and urgency.

Regardless of the kind of problem that arise during the on-call service, judges have to make decisions, and they usually solve them by informally contacting senior colleagues (which is unlikely when a situation takes place at 4 a.m.), or relying on their intuition and common sense.

With time, judges acquire a great amount of this practical experience. Nevertheless, the Spanish judicial system requires them to promote to upper-level positions after a short period. In these new positions, they will hardly reuse this knowledge, and at the same time new junior judges will fill those low court positions and will have to start the learning process from scratch. Since the legal organization does not provide their members with the means of sharing this practical knowledge, a part of the memory of these organizational units is systematically lost or only informally distributed.

According to the previously presented process for organizational memory management, once certain solutions have been successfully worked out, the knowledge attached to them would enrich the organizational memory with practical routines to deal with similar on-call situations. However, the fact that legal knowledge management systems have typically focused on procedural – that is, written — legal documents hampers their ability to manage this practical knowledge.

In conclusion, the fact that a legal organization neither offers nor maintains a set of ready-made solutions for usual problems faced by its professionals not only challenges their own members’ professional role, but it also handicaps the learning capacity of the organization itself. In turn, it makes particular organizational units more vulnerable to potential problems, such as conflict of interests or organizational slack.

The challenge of practical knowledge

Important advances in knowledge engineering, text mining, and information retrieval have been made that enable formalizing, interpreting and storing different types of knowledge. Therefore, knowledge management systems can more easily be implemented to improve organizational design.

However, professional, practical knowledge cannot be easily incorporated into the organizational memory, because it may not be found in documents from which it may be directly acquired, extracted and modeled. Furthermore, most organizations may be unaware of the existence of certain key practical knowledge among the staff, and thus also unaware of the need to include it into their organizational memories.

From my experience in the research involving the on-call service, it seems imperative that serious empirical assessments of the processes by which decisions are made — and thus knowledge is produced — within legal organizations should be incorporated in every project, along with the knowledge modeling techniques that can build more efficient knowledge- and information- management tools.

Joan-Josep Vallbé is a researcher at the Institute of Law and Technology (IDT) of the Autonomous University of Barcelona. He is also a lecturer in political science at the Political Science Department of the University of Barcelona. He recently finished and presented his PhD thesis on decision-making within organizational frameworks. His research interests include the use of text mining and text statistics for organizational analysis, and the development of performance indicators on the management of organizational memories.

Joan-Josep Vallbé is a researcher at the Institute of Law and Technology (IDT) of the Autonomous University of Barcelona. He is also a lecturer in political science at the Political Science Department of the University of Barcelona. He recently finished and presented his PhD thesis on decision-making within organizational frameworks. His research interests include the use of text mining and text statistics for organizational analysis, and the development of performance indicators on the management of organizational memories.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt.