In order to agree to write about something that is 25 years old, you almost have to admit to being old enough to have something to say about it. So I might as well get my old codger bona fides out of the way. I came of age at the very cusp of the digital revolution in legal information. A month before my college graduation ceremony in June 1981, IBM launched its first PC. I thus belong to the last generation of students who produced their term papers on a typewriter.

The Former Next Great Thing

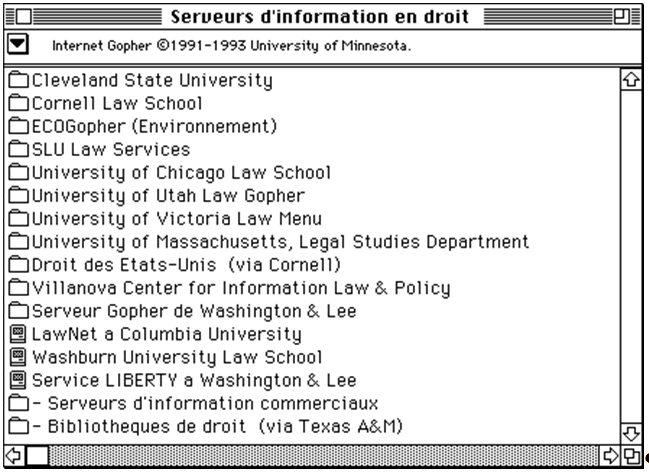

When I later entered law school the PCs were pretty well established (we used WordPerfect to write our briefs, of course), and the cutting edge of technology shifted to new legal research tools. Between trips to the library stacks to track down digests or to tediously Shepardize cases manually, we learned of Lexis and Westlaw, which in my first year were accessed via an acoustic-coupled modem and an IBM 3101 dumb terminal, squirreled away in a tiny lab-like room next to the reference desk in the library. One terminal to serve an entire law school. Sign up to use it via a schedule on the door. Intrigued by this new world of digital information, I took a job in the law library, eventually teaching other students how to search on Lexis and Westlaw between shifts at the reference desk.

By my second or third year, the 3101 was replaced by Lexis’ and Westlaw’s UBIQ and WALT dedicated terminals. My boss Tom Woxland, Reference Librarian and Head of Public Services at the University of Minnesota Law School, wrote an amusing article in Legal Reference Services Quarterly about a conflict between WALT and the library staff’s refrigerator that will give you a good sense of the level of technology sophistication we dealt with on a daily basis in those days.

It was just a few years after this refrigerator incident that Tom Bruce and Peter Martin started up LII. It’s hard to underestimate the imagination and vision that this must have taken, because the digital legal world was still in its infancy. But they could see the way the world was headed in 1992, and not only that, they did something about it in starting LII.

UBIQ and WALT, locked away in that room in the library, awakened an interest that turned into a career in legal information systems. I gradually lost interest in legal practice as a career as my interest in electronic information systems of all kinds grew. By the time I first met Tom Bruce, it was in my capacity as a token representative of the commercial side of the legal information world; I was an analyst at the research firm Outsell, Inc., which tracks various information markets, and I covered Thomson Reuters, Reed Elsevier (RELX), Wolters Kluwer, and all of the smaller players nipping at their heels in the legal information hierarchies of the time. Tom called on me to help explain this commercial world to his community of people working in the more open and non-commercial part of the legal information landscape.

I don’t intend this piece to be a tribute to LII, nor was I asked to provide one. Rather, Tom Bruce asked me to say a few words about the relationship between free and fee-based legal materials and how they relate to each other. In one big sense, that relationship has evolved in the face of new technologies, and that evolution is the focus of this essay. A fundamental shift in the way the legal market approaches legal information is underway: We no longer think of legal information simply as sets of documents; we are starting to see legal information as data.

To go back to the chronicle of my digital awakening, there were several things about the new legal information systems that excited me even way back in the 1980s:

- New entry points. Free-text searching in Westlaw and Lexis freed us from having to use finding tools such as digests, legal encyclopedia, and secondary analytical legal literature in order to find relevant cases. Suddenly any aspect of a case was open to search, not just those that legal indexers or secondary legal materials might have chosen to highlight. Dan Dabney, the former Senior Director, Classification Services at Thomson Reuters, wrote a thoughtful piece about the relationship between searching the natural language of the law, on the one hand, and the artificial languages like the Key Number System that we use to describe the law. He identified the advantages and disadvantages of both, but it was clear that free-text search was a leap forward. His article has held up well and is worth a read: The Universe of Thinkable Thoughts: Literary Warrant and West’s Key Number System

- Universal availability. Another aspect of the new legal databases that seemed obvious to me pretty early on was that comprehensive databases of electronic legal materials would be available anywhere, anytime. This had implications for the role of libraries, and for the workflow of lawyers. It also had access to justice implications, because while most law libraries were open to the public and free (if inconvenient to use), online databases were, at the time, mostly commercial operations with paywalls. If theoretically available anytime and anywhere, legal materials were nonetheless limited to those who could invest the money to subscribe and the time to master their still-complex search syntax.

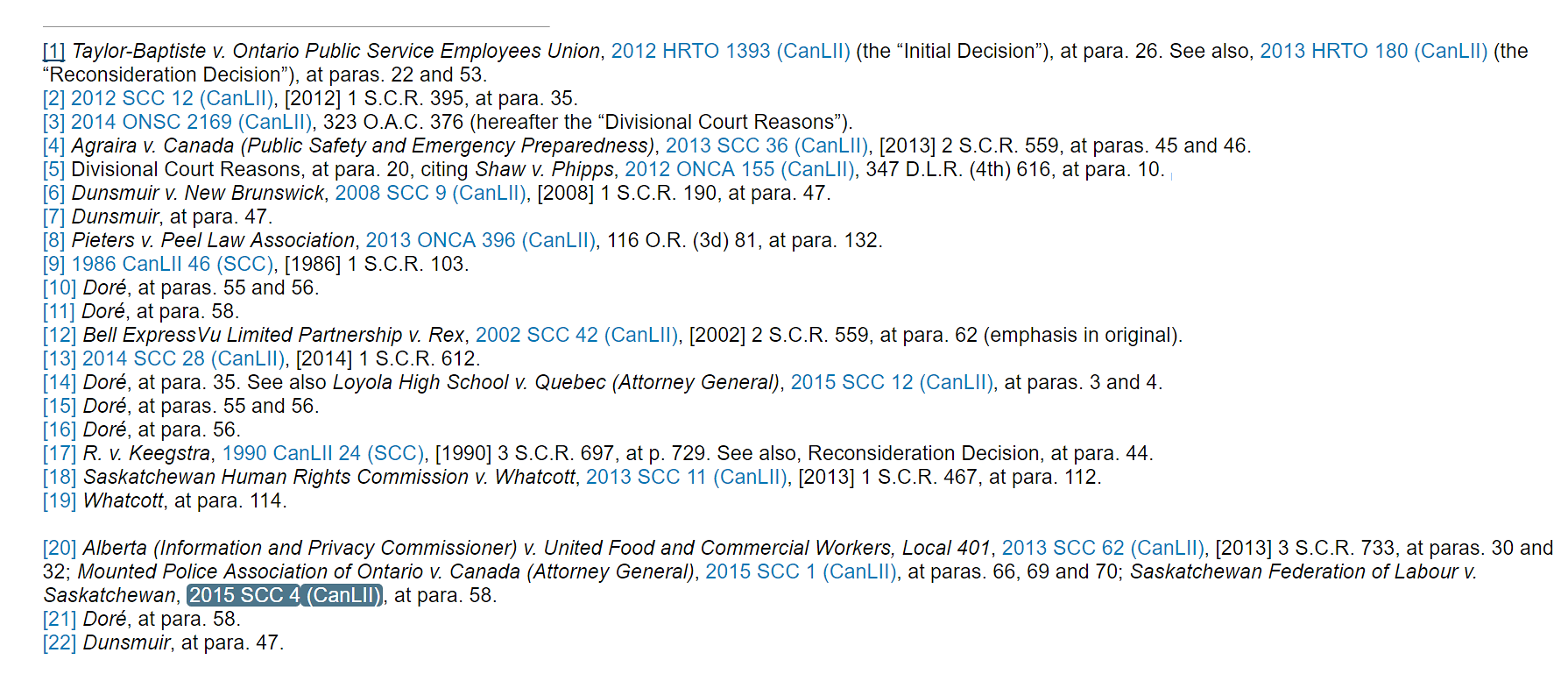

- Hyperlinking. While the full hyperlinking possibilities of the World Wide Web were a decade off, I could see that online access to legal materials would shorten the steps between legal arguments and supporting sources. Where before one might jot down a series of case citations in a text and then go to the stacks one by one to evaluate their relevancy, online you could do this all in one sitting. The editorial cross-referencing that already went in annotations, footnotes, and in-line cites in cases was about to become an orgy of cross-linking (across all kinds of content, not just legal content) that could be carried out at the click of a mouse.

But as revolutionary as these new approaches were, electronic legal research systems still operated primarily as finding tools. The process of legal research was still oriented toward a single goal: leading the researcher to the documents that contained the answers to legal questions. The onus was still on lawyers to extract meaning from those documents and embed that meaning in their work product.

A New Mindset: Data not Documents

In recent years, however, a shift in mindset has occurred. Some lawyers, with the help of data scientists, are now starting to think of legal information sources not as collections of individual documents that need to stand on their own in order to have meaning, but as data sets from which new kinds of meaning can be extracted.

Some of those new applications for “law as data” are:

- Lawyer and court analytics. Lex Machina and Ravel Law, recently acquired by LexisNexis, are poster boys for this phenomenon, but others are joining the fray. Lex Machina takes court docket information and analyzes them not for their legal content but for performance data – how fast does this court handle a certain kind of motion, how well has that firm performed. The goal is to identify trends and make predictions based on objective performance data, which is quite a different inquiry than looking at a case based on the merits alone.

- Citation analysis and visualization The value of it is open to discussion, but some commercial players are bringing new techniques to citation analysis, and quite often the result is some form of visualization. Ravel Law and Fastcase have various kinds of visualizations that take sets of case law data and turn them into visual representations that are intended to illuminate and reveal relationships that traditional, more linear citation analysis might not find.

- Usage analysis. The content of documents is valuable, but so are the trails of crumbs that users leave as they move from one document to another. Finding meaning in those patterns of usage is just as useful for lawyers as it is for consumers in the Amazon age of “people who bought this also bought that.” Knowing where other researchers have been is valuable data, and systems like Westlaw are able to track relationships between documents and leverage them as information that can be as valuable as any editorial classification scheme.

- Entity extraction. Legal documents are full of named entities: people, companies, product names, places, other organizations. Computers are getting better at finding and extracting those entity names from documents. This has a number of utilities, beyond just helping to standardize the nomenclature used within a data source. Open standards for entity names mean legal data can more easily be integrated with other types of data sources. One such open standard identifier is Thomson Reuters’ PermID.

- Statutes and regulations as inputs to smart contracts. It’s only a matter of time before large classes of contracts become automated and self-executing smart contracts supported by distributed ledgers and blockchains. A classic example of such a smart contract is a shipping contract, where one party is obligated to pay another when goods arrive in a harbor, and GPS data on the location of a ship can be the signal that triggers such payment. But electronically stored statutes and regulations, especially to the extent that they govern quantitative measures such as time frames, currencies, or interest rates, can also become inputs to smart contracts, dynamically changing contract terms or triggering actions or obligations without human (i.e. lawyerly) intervention.

In all of these applications, we are moving quite a bit away from seeing legal documents for their “face value,” the intrinsic legal principles(s) that each document stands for. Rather, documents and interrelated sets of documents are sources of data points that can be leveraged in different ways in order to speed up and/or improve legal and business decisions. The data embedded in sets of legal documents becomes more than simply the sum of their content in substantive legal meaning; other meanings with strategic or commercial value can be surfaced.

The Future: Better Data, Not Just Open Data

If there is one thing that the application of a lot of data science to the law has revealed, it’s that the law is a mess. Certain jurisdictions are better than others, of course, but in the US the raw data that we call the law is delivered to the public in an unholy variety of formats, with inconsistent frequency, various levels of comprehensiveness, and with self-imposed limitations on access. On the state level alone, Sarah Glassmeyer, in her State Legal Information Census, identified 14 different barriers to access ranging from lack of search capability to lack of authoritativeness to restrictions on access for re-use. Add to that the problematic publishing practices at the federal level (Pacer, anyone?) and the free-for-all at the county and municipal levels, and it’s nothing less than an untamed data jungle.

It is notoriously difficult to acquire and analyze what has been called the operating system of democracy, the law. When Lex Machina was acquired by LexisNexis, one of the primary motivations it gave was the high cost of acquiring, and then normalizing, the imperfect legal data that comes out of the federal courts. LexisNexis had already made the significant investment in building that data set; Lex Machina wanted to focus on what it was good at rather than on than spending its time acquiring and cleaning up the government’s data.

When a large collection of US case law was made available to the public via Google Scholar in 2009, many saw this as the beginning of the end. Finally, they thought, access to the law would no longer be a problem. Since then, more and more legal sources – judicial, legislative, and administrative – have been brought to the public domain. But is that kind of access the beginning of the end, or the end of the beginning? Or the beginning of a new mission?

In a thoughtful 2014 essay about Google Scholar’s addition of case law, Tom Bruce reminded us not to get too self-congratulatory about simple access to legal documents. Wider and freer availability of legal documents does solve one set of problems, especially for one set of users: lawyers. For the public at large, however, even free and open legal information is as impenetrable as if it had been locked up behind the most expensive paywalls. The reason for this is that most legal information is written and delivered as if only lawyers need it. In his essay, he sees the “what’s next” for the Open Access movement as opening legal information to the people who despite not being lawyers, are nonetheless affected by the law every minute of their lives.

Yes, that “what next” does include pushing to make more primary legal documents freely available in the public domain. Yes, it does mean that organizations like LII can continue to help make law and regulations easier for non-lawyers to find, understand, and apply in their lives, jobs, and industries. But Tom Bruce provided a few hints at what is now clearly an equally important imperative. Among his prescriptions for the future: “We need to increase the density of connections between documents by making connections easier for machines (rather than human authors) to create.”

Operating in a “law as data” mindset, lawyers, legal tech companies, and data-savvy players of all kind will be looking for cleaner, more well-structured, more machine-readable, and more consistently-formatted legal data. I think this might be a good role for the LIIs of the world in the future. Not instead of, but in addition to, the core mission now of making raw legal content more available to everyone. In a 2015 article, I lamented the fact that so much legal technology expertise is wasted on simply making sense of the unstructured mess found in legal documents. Someday, all the effort used to make sense of messy data might stimulate a movement to make the data less messy in the first place. I cited Paul Lippe on this, in his discussion of the long-term effects of artificial intelligence in the legal system: “Watson will force a much more rigorous conversation about the actual structure of legal knowledge. Statutes, regulations, how-to-guides, policies, contracts and of course case law don’t work together especially well, making it challenging for systems like Watson to interpret them. This Tower of Babel says as much about the complex way we create law as it does about the limitations of Watson.”

LII and the Free Access to Law Movement have spent 25 years bringing the legal Tower of Babel into the sunlight. A worthy goal for the next 25 years would be to help guide that “rigourous conversation about the structure of legal knowledge.”

David Curle is the director of Market Intelligence at Thomson Reuters Legal, providing research and thought leadership around the competitive environment and the changing legal services industry.