One could wonder what Jeremy Bentham would have thought of the 4 billion people who ar e currently excluded from the rule of law. That number comes from a 2008 report of the United-Nations Development Program’s Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor (UNDP-CLEP). The British philosopher’s vision of “every man his own lawyer” certainly finds an echo in the UNDP-CLEP assertion that:

e currently excluded from the rule of law. That number comes from a 2008 report of the United-Nations Development Program’s Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor (UNDP-CLEP). The British philosopher’s vision of “every man his own lawyer” certainly finds an echo in the UNDP-CLEP assertion that:

Empowering the poor through improved dissemination of legal information and formation of peer groups (self-help) are first-step strategies towards justice. Poor people may not receive the protection or opportunities to which they are legally entitled because they do not know the law or do not know how to go about securing the assistance of someone who can provide the necessary help. Modern information and communication technologies are particularly well suited to support interventions geared towards strengthening information-sharing groups, teaching the poor about their rights, and encouraging non-formal legal education. (p. 64)

Without actually saying it, the UNDP-CLEP seems to be describing what some call Web 2.0 or the participative web. In fact, these represent a series of tools and technologies, such as blogs, wikis, social networks, and content hosting and sharing sites, which allow many individuals to collaborate. Tools and communities are precisely what are required for a good old-fashioned barn raising–except, of course, for a green pasture on which to erect it !

This is where the global open access to law movement comes in. My goal, humbly submitted to the VoxPopuLII community for review, is to attempt to model how Web 2.0 and collaboration could be used to bring forth a greater understanding of the law in society, using the Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLII) as a model and working with Daniel Poulin of the Université de Montréal’s LexUM. The full version of my findings can be found in my master’s thesis (en français) as well as in a paper submitted at the Law via the Internet Conference in November 2009 (my slides are hosted here).

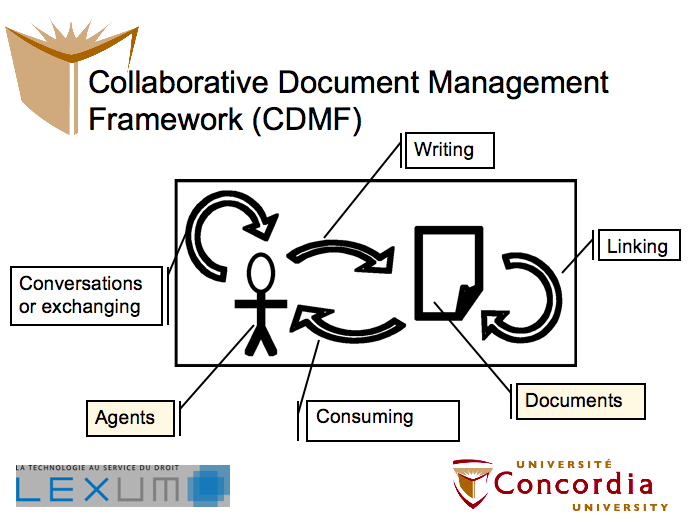

I first set out to describe and define both Web 2.0 and collaboration. After a review of various theories and tools, I offer the following visual summary, which I call the Collaborative Document Management Framework (CDMF):

In this model, I posit that Agents — people like you and me as well as institutions or information services — and documents — such as court cases, newspaper articles and books — interact with each other in four generic relationships. Agents engage in conversations or exchanges, documents link or refer to each other, while agents consume or read documents, and documents are written by agents.

Manifestations of these relationships abound. For example, people exchange views via the comment or trackback function of blogs or through open letters in newspapers. A journalist covering a recent Supreme Court ruling is writing a document (her article) while linking to the ruling (although implicitly). Individuals accessing a statute in a public library are consuming the document.

Collaborative digital technologies offer the potential to explicitly keep track of all these interactions. In turn, these data could yield a great deal of insight on which bits of legal information are useful to whom. My goal was to explore how this could come about in a conceptual sense, hopefully offering some guidance by pointing out key success factors from a variety of examples. [Please note that this is in fact a theoretical exercise from my own personal point of view and does not reflect the position of the Canadian Legal Information Institute.]

Here are some ideas that could foster a vision of collaboration within the context of open access to law, using my own blogging experience as an example. I have always entertained an unhealthy fascination with the interaction of law and information. I revel in the paradoxes that arise from the tension between libel and freedom of expression, privacy and freedom of the press, government secrecy and the right of access to information, economic imperatives and fair or private copying …. This means that my personal consumption habits of legal information usually revolve around these topics, particularly discussing court cases and pointing out issues in the law. I currently use a simple blog for this function (CultureLibre.ca), and I know there are many of us out there, be they practicing lawyers, academics, laypeople or others.

Counting beans: developing a citation tool for legal documents

When I want to cite a paragraph of a court ruling, I simply copy-paste the snippet of text into my blog. This is a bit unfortunate as there is a lost opportunity. Imagine a system by which a user highlights a bit of text on an open access legal website, clicks on a button and is offered a bit of code to place in her blog (instead of the direct copy-pasting).

This bit of code, akin to what allows users repost YouTube videos, could create a box on the blog where the legal text is shown. If the statute were to be amended or the court decision reversed on appeal, the box could display a code (say, a red flag) alerting readers of the change. On the other side, the open access legal website would be able to keep track of every time this blog is read, providing a precise metric of use, useful for relevancy statistics.

Another powerful use of this mechanism would be to offer users of the open access legal website the links to the various blog postings when they hover over the quote in the original legal text. A simple voting system could offer a way for the community to regulate itself. Similarly, users could turn this feature on or off in their personal settings.

Let the data in: building better bibliographic tools

On my blog, I keep track of relevant newspaper or research articles as well as books or government reports. Compiling all this bibliographic data is a painstaking but rewarding process, as it saves me much time in the long run. If I could add this information via a web form into an open access legal information website, this process could be streamlined. After a while, one could find that some documents are already within the system, which would save time. As well, a diligent operator of an open access legal website could obtain bibliographic data in bulk either from vendors or from library catalogues.

In turn, users could be offered tools to link bibliographic data with legal documents, offering a richer browsing experience. Imagine having a list of recommended reading available directly from a specific statute or court ruling as described in the previous point, as certain commercial vendors are already doing. In fact, the real power would lie in the ability to link to a specific article in a law or a specific (short) passage in a court ruling. Creating anchors on the fly and linking back and forth would yield immense value.

People are suckers for popularity

The previous examples imply that one can register on such a website. This allows for a much richer browsing experience through personalized settings and interface customization. Most users are now accustomed to this and even expect it from contemporary websites, such as existing social networking websites. This provides the added benefit of determining the relative value of a single user’s contribution, based on how others vote.

Slashdot offers a similar mechanism, where some users are also reviewers and may agree or disagree with a comment. In fact, some legal social networking platforms already allow for this feature. What would be needed is a mechanism to link to snippets of legal text, perhaps as an add-on to legal social networking sites…

Its all about granular information

Computers are better at dealing with granular information, such as a date, or a piece of code. Textual information is better left for humans. That is why operators of open access legal websites should focus on identifying ways to trick users into giving them bits of data, not text, unless it is from a highly regarded member of the community or a trusted source (such as a judge). A simple agree/disagree vote is much better than a text box where one could write their objections. If people feel the urge to write, they should start their own blogs.

Insofar as the open access legal information website is concerned, there are only a few elements of value in this scenario — for example, when the blogger quotes a court case or statute. It would be hard to evaluate what is said without the intervention of a human operator. That is why the feedback mechanism between users (the agree/disagree button) is a useful way to allow for a very minimal amount of discussion while still being able to derive value from this process.

Parting words

Many of you are probably thinking of a flipside to what I propose. What happens if the information provided on blog-posts is wrong? What is the legal risk of blogging? What of legal advice from individuals who are not members of the Bar?

I have to admit that I am very concerned with these issues. I am tempted to say that an information-literate individual will apply due diligence to any information that is available — online or otherwise. As we all know, legal battles usually oppose two very crystallized visions of a rule or norm. One can find two sides to a story — or more. These debates add value to civil society, but one has to be aware of them. And that is not even getting into distinguishing strategies in common law!

The position I think most defensible in my proposed way forward is the following. In the practice of law, lawyers hold a monopoly in legal procedure as well as in giving legal advice within an individual case. In online communities, however, I would certainly hope that we, laypeople and jurists alike, may still discuss the law in general terms. There is a fine line to walk, but it is important for the legal community to recognize that the more people talk about the law, the more our society benefits from the Rule of Law, as Jeremy Bentham asserted.

As a side note, I would even wager that the need for legal services in a society is directly proportional to the number of legal topics discussed by laypeople in that society. But perhaps this is the subject of yet another post …

In any case, I hope this paper will provide the opportunity to discuss some of the ideas that could bring digital collaboration to the open access to law movement. I invite you to also download my full paper for additional insight on this question. Also, I will be presenting some of these issues at the Legal IT conference in Montréal on April 26-27 2010. Perhaps this could be an opportunity to engage in a conversation about this issue?

In any case, I hope this paper will provide the opportunity to discuss some of the ideas that could bring digital collaboration to the open access to law movement. I invite you to also download my full paper for additional insight on this question. Also, I will be presenting some of these issues at the Legal IT conference in Montréal on April 26-27 2010. Perhaps this could be an opportunity to engage in a conversation about this issue?

Thanking you for your interest in my work,

Olivier Charbonneau

Associate Librarian, Concordia University (Montreal, Canada)

Doctoral candidate, Faculty of Law, Université de Montréal

www.culturelibre.ca

The author would like to thank his employer for supporting him in his research.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor in Chief is Rob Richards.

In 2004,

In 2004,  Courts have gradually been adopting the neutral citation, beginning in 1999 and continuing to the present. The first adopter of the neutral citation was the

Courts have gradually been adopting the neutral citation, beginning in 1999 and continuing to the present. The first adopter of the neutral citation was the