In May of this year, HeinOnline began taking a new approach to legal research, offering researchers the ability to search or browse varying types of legal research material all related to a specialized area of law in one database. We introduced this concept as a new legal research platform with the release of World Constitutions Illustrated: Contemporary & Historical Documents & Resources, which we’ll discuss in further detail later on in this post. First, we must take a brief look at how HeinOnline started and where it is going. Then, we will continue on by looking at the scope of the new platform and how it is being implemented across HeinOnline’s newest library modules.

This is how we started…

Traditionally, HeinOnline libraries featured one title or a single type of legal research material. For example, the Law Journal Library, HeinOnline’s largest and most used database, contains law and law-related periodicals. The Federal Register Library contains the Federal Register dating back to inception, with select supporting resources. The U.S. Statutes at Large Library contains the U.S. Statutes at Large volumes dating back to inception, with select supporting resources.

This is where we are going…

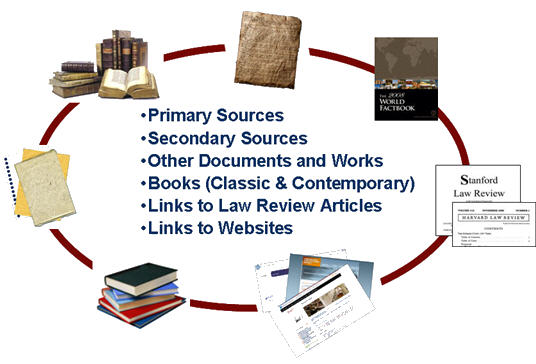

The new subject-specific legal research platform, introduced earlier this year, has shifted from that traditional approach to a more dynamic approach of offering research libraries focused on a subject area, versus a single title or resource. This platform combines primary and secondary resources, books, law review articles, periodicals, government documents, historical documents, bibliographic references and other supporting resources all related to the same area of law, into one database, thus providing researchers one central place to find what they need.

How is this platform being implemented?

In May, HeinOnline introduced the platform with the release of a new library called World Constitutions Illustrated: Contemporary & Historical Documents & Resources. The platform has since been implemented in every new library that HeinOnline has released including History of Bankruptcy: Taxation & Economic Reform in America, Part III and Intellectual Property Law Collection.

Pilot project: World Constitutions Illustrated

First, let’s look at the pilot project, World Constitutions Illustrated. Our goal when releasing this new library was to present legal researchers with a different scope than what is currently available for those studying constitutional law and political science. To achieve this, the library was built upon the new legal research platform, which brings together: constitutional documents, both current and historical; secondary sources such as the CIA’s World Fact Book, Modern Legal Systems Cyclopedia, the Library of Congress’s Country Studies and British and Foreign State Papers; books; law review articles; bibliographies; and links to external resources on the Web that directly relate to the political and historical development of each country. By presenting the information in this format, researchers no longer have to visit multiple Web sites or pull multiple sources to obtain the documentary history of the development of a country’s constitution and government.

Inside the interface, every country has a dedicated resource page that includes the Constitutions and Fundamental Laws, Commentaries & Other Relevant Sources, Scholarly Articles Chosen by Our Editors, a Bibliography of Select Constitutional Books, External Links, and a news feed. Let’s take a look at France.

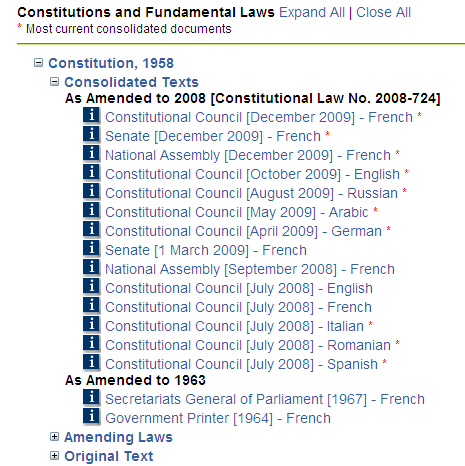

Constitutions & Fundamental Laws

France has a significant hierarchy of constitutional documents from the current constitution as amended to 2008 all the way back to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen promulgated in 1789. Within the hierarchy of documents, one can find consolidated texts, amending laws, and the original text in multiple languages when translations are available.

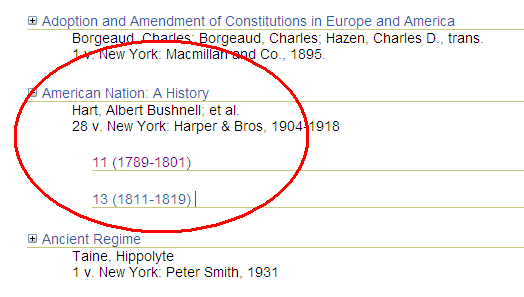

Commentaries & Other Relevant Sources

Researchers will find more than 100 commentaries and other relevant sources of information related to the development of the government of France and the French Constitution. These sources include secondary source books and classic constitutional law books. To further connect these sources to the French Constitution, our Editors have reviewed each source book and classic constitutional book and linked researchers to the specific chapters or sections of the works that directly relate to the study of the French Constitution. For example, the work titled American Nation: A History, by Albert Bushnell Hart, has direct links to chapters from within volumes 11 and 13, each of which discusses and relates to the development of the French government.

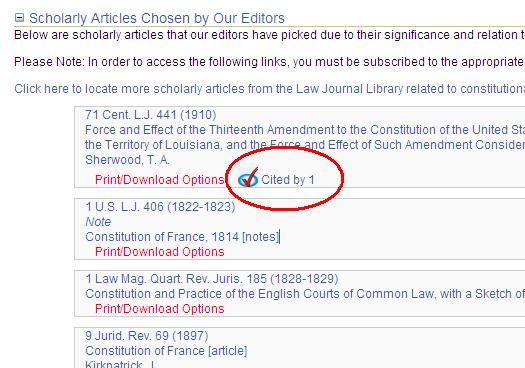

Scholarly Articles Chosen by Our Editors

This section features more than 40 links to scholarly articles from HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library that are directly related to the study of the French Constitution and the development of the government of France. The Editors hand-selected and included these articles from the thousands of articles in the Law Journal Library due to their significance and relation to the constitutional and political development of the nation. When browsing the list of articles, one will also find Hein’s ScholarCheck integrated, which allows a researcher to view other law review articles that cite that specific article. In order for researchers to access the law review articles, they must be subscribed to the Law Journal Library.

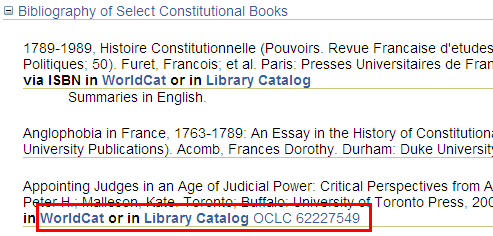

Bibliography of Select Constitutional Books

There are thousands of books related to constitutional law. Our Editors have gone through an extensive list of these resources and hand-selected books relevant to the constitutional development of each country. The selections are presented as a bibliography within each country. France has nearly 100 bibliographic references. Many bibliographic references also contain the ISBN which links to WorldCat, allowing researchers to find the work in a nearby library.

External Links

External links are also selected by the Editors as they are developing the constitutional hierarchies for each country. If there are significant online resources available that support the study of the constitution or the country’s political development, the links are included on the country page.

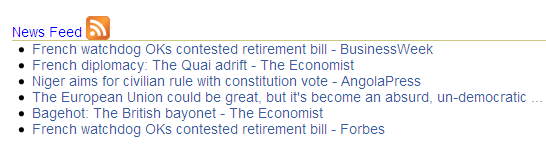

News Feeds

The last component on each country’s page is a news feed featuring recent articles about the country’s constitution. The news feed is powered by a Google RSS news feed and researchers can easily use the RSS icon to add it to their own RSS readers.

In addition to the significant and comprehensive coverage of every country in World Constitutions Illustrated, the collection also features an abundance of material related to the study of constitutional law at a higher level. This makes it useful for those researching more general or regional constitutional topics.

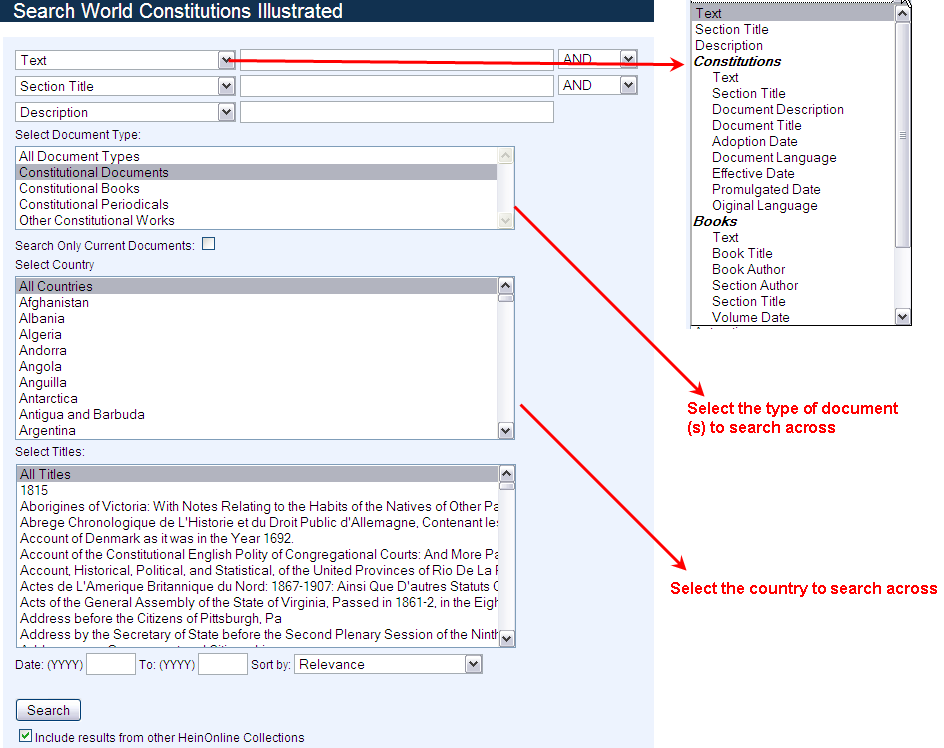

Searching capabilities on the new platform

To further enhance the capabilities of this platform, researchers are presented with a comprehensive search tool that allows one to search the documents and books by a number of metadata points including the document date, promulgated date, document source, title, and author. For researchers studying the current constitution, the search can be narrowed to include just the current documents that make up the constitution for a country. Furthermore, a search can be generated across all the documents, classic books, or reference books for a specific country, or it can be narrower in scope to include a specific type of resource. After a search is generated, researchers will receive faceted search results, allowing them to quickly and easily drill down their results set by using facets including document type, date, country, and title.

Contributing to the project

An underlying concept behind the new legal research platform is encouraging legal scholars, law libraries, subject area experts, and other professionals to contribute to the project. HeinOnline wants to work with scholars and libraries from all around the world to continue to build upon the collection and to continue developing the constitutional timelines for every country. Several libraries and scholars from around the world have already contributed constitutional works from their libraries to World Constitutions Illustrated.

Extending the platform beyond the pilot project

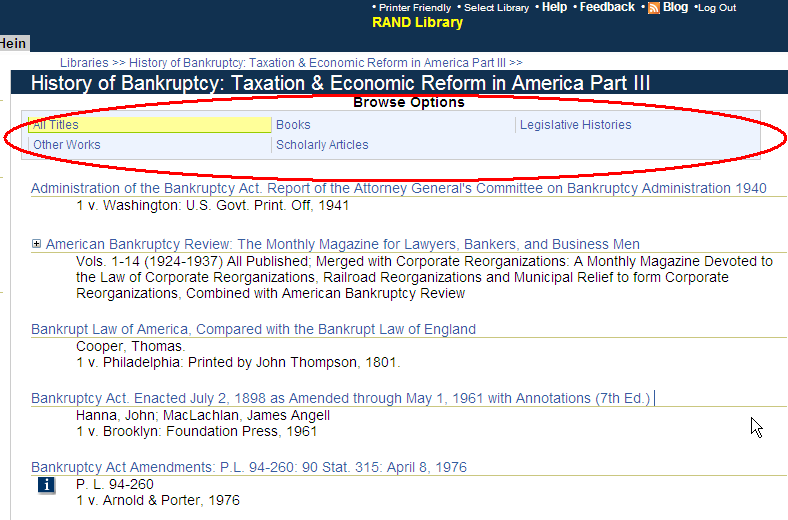

As mentioned earlier, this platform has been implemented in every new library that HeinOnline has released including History of Bankruptcy: Taxation & Economic Reform in America, Part III and Intellectual Property Law Collection. Therefore, it’s necessary to briefly take a moment to look at these two libraries.

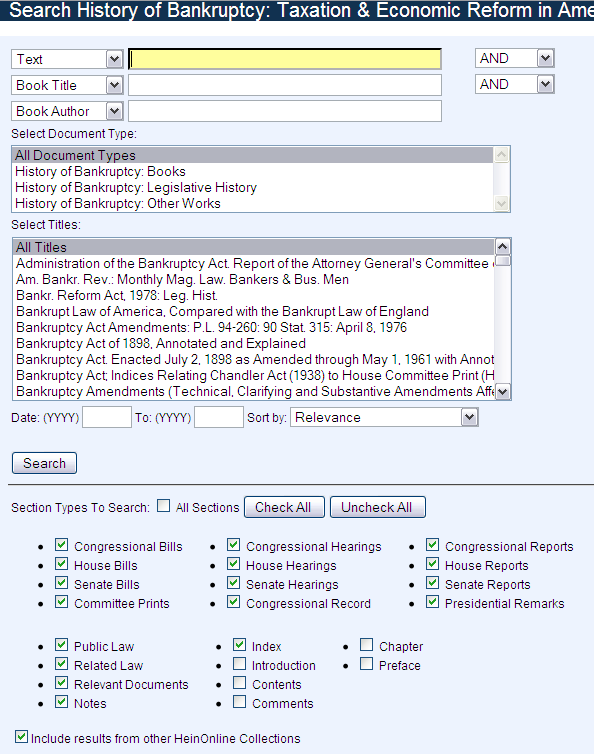

History of Bankruptcy: Taxation & Economic Reform in America, Part III

The History of Bankruptcy library includes more than 172,000 pages of legislative histories, treatises, documents and more, all related to bankruptcy law in America. The primary resources in this library are the legislative histories, which can be browsed by title, public law number, or popular name. Also included are classic books dating back to the late 1800’s and links to scholarly articles that were selected by our editors due to their significance to the study of bankruptcy law in America.

As with the searching capabilities presented in the World Constitutions Illustrated library, researchers can narrow a search by the type of resource, or search across everything in the library. After a search is generated, researchers will receive faceted search results, allowing them to quickly and easily drill down their results set by document type, date, or title.

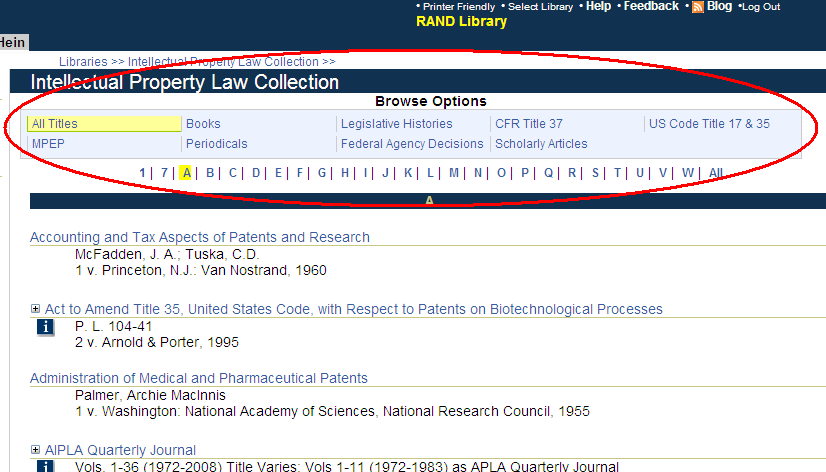

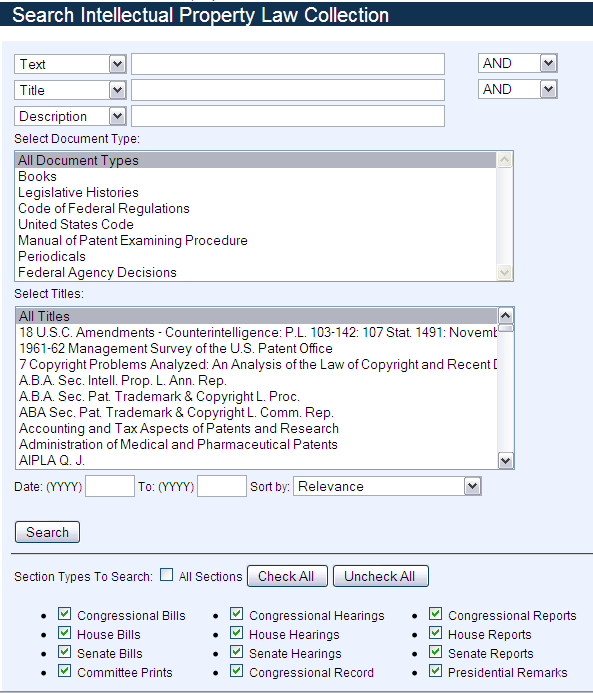

Intellectual Property Law Collection

The Intellectual Property Law Collection, released just over a month ago, features nearly 2 million pages of legal research material related to patents, trademarks, and copyrights in America. It includes more than 270 books, more than 100 legislative histories, links to more than 50 legal periodicals, federal agency documents, the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure, CFR Title 37, U.S. Code Titles 17 & 35, and links to scholarly articles chosen by our Editors, all related to intellectual property law in America.

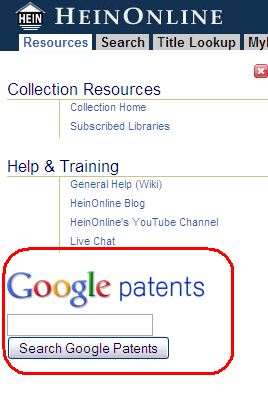

Furthermore, this library features a Google Patent Search widget that will allows researchers to search across more than 7 million patents made available to the public through an arrangement with Google and the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

Searching in the Intellectual Property Law Collection allows researchers to search across all types of documents, or narrow a search to just books, legislative histories, or federal agency decisions, for example. After a search is generated, researchers will receive faceted search results, allowing them to quickly and easily drill down their results set by using facets including document type, date, country, or title.

HeinOnline is the modern link to legal history, and the new legal research platform bolsters this primary objective. The platform brings together the primary and secondary sources, other supporting documents, books, links to articles, periodicals, and links to other online sources, making it a central stop for researchers to begin their search for legal research material. The Editors have selected the books, articles, and sources that they deem significant to that area of the law. This is then presented in one database, making it easier for researchers to find what they need. With the tremendous growth of digital media and online sources, it can prove difficult for a researcher to quickly navigate to the most significant sources of information. HeinOnline’s goal is to make this navigation easier with the implementation of this new legal research platform.

Marcie Baranich is the Marketing Manager at William S. Hein & Co., Inc. and is responsible for the strategic marketing processes for both Hein’s traditional products and its growing online legal research database, HeinOnline. In addition to her Marketing role, she is also active in the product development, training and support areas for HeinOnline. She is an author of the HeinOnline Blog, Wiki, YouTube channel, Facebook, and Twitter pages, and manages the strategic use of these resources to communicate and assist users with their legal research needs.

Marcie Baranich is the Marketing Manager at William S. Hein & Co., Inc. and is responsible for the strategic marketing processes for both Hein’s traditional products and its growing online legal research database, HeinOnline. In addition to her Marketing role, she is also active in the product development, training and support areas for HeinOnline. She is an author of the HeinOnline Blog, Wiki, YouTube channel, Facebook, and Twitter pages, and manages the strategic use of these resources to communicate and assist users with their legal research needs.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt.

Editor-in-Chief is Robert Richards, to whom queries should be directed.