Last Tuesday Judge Denny Chin refused to grant the plaintiffs’ motion for final approval of the Google Books Amended Settlement Agreement (“ASA”), finding that the ASA is not fair, adequate, or reasonable. The opinion is available here, and worth the quick read (students, you may be interested to see that Judge Chin uses several law review articles to provide background information about the case and its implications). Judge Chin, in analyzing whether the agreement met the requirements of Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 23(e), applied the factors articulated in City of Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 495 F.2d 448 (2d Cir. 1974). He found that most of the Grinnell factors favored approval, i.e.:

Last Tuesday Judge Denny Chin refused to grant the plaintiffs’ motion for final approval of the Google Books Amended Settlement Agreement (“ASA”), finding that the ASA is not fair, adequate, or reasonable. The opinion is available here, and worth the quick read (students, you may be interested to see that Judge Chin uses several law review articles to provide background information about the case and its implications). Judge Chin, in analyzing whether the agreement met the requirements of Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 23(e), applied the factors articulated in City of Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 495 F.2d 448 (2d Cir. 1974). He found that most of the Grinnell factors favored approval, i.e.:

- litigation has been complex, expensive, and lengthy

- the case has been pending since 2005

- the outcome of the case, were it to go to trial, is in substantial doubt

- maintaining the class throughout the litigation is risky

One factor however, weighed substantially against approving the settlement: the many negative reactions of class members, which Judge Chin summarized as follows:

- Adequacy of class notice. Judge Chin rejected this objection.

- Adequacy of class representation. Judge Chin found there to be an issue regarding the existence of competing interests between class members.

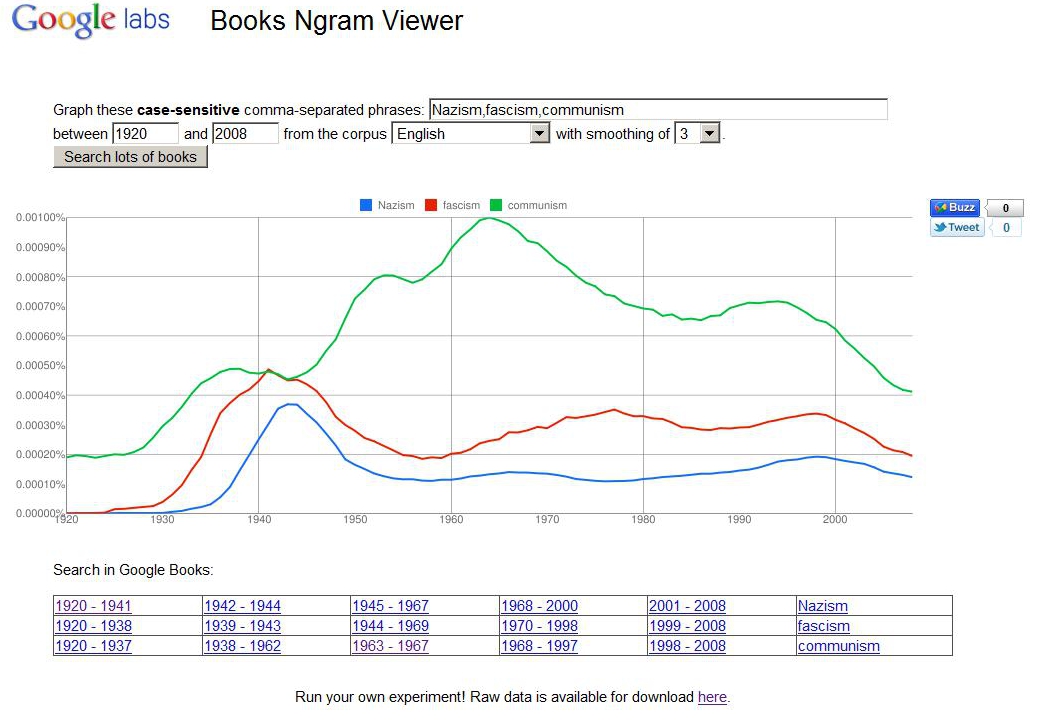

- Scope of relief under Rule 23. The judge found that the scope of the settlement goes beyond permissible bounds in several respects. First, the settlement reshapes copyright law related to orphan works and affects international copyright law, which are matters more properly determined by Congress. Second, the settlement goes far beyond the boundaries of the complaint, which was limited to the scanning and display of “snippets” by giving Google the ability to digitize and sell copies of millions of books, including books still protected by copyright. Third, the interests of some class members have not been adequately represented, such as academic authors who may prefer free access to their copyrighted books and the copyright holders to orphan works, who have a conflict of interest with Google. Fourth, the agreement violates copyright law by requiring copyright holders to take affirmative action to prevent the scanning of their books. Fifth, the settlement grants Google a monopoly over orphan books and increased Google’s position in the search market. Sixth, some objectors have concerns that consumers will lose privacy in their reading habits to Google, but Judge Chin rejected this concern due to Google’s safeguards. Seventh and lastly, despite the removal of certain foreign works from the ASA, foreign copyright holders continue to object that the settlement will affect their works and violate the international copyright law.

So what’s next? In closing, Judge Chin informed the parties that he may approve the settlement if it were changed to an “opt-in” agreement from an “opt-out” agreement. This option is extremely unattractive to Google because it significantly decreases Google’s ability to exploit the books it has digitized so far.

So what is next? A status conference is scheduled for April 25. Google has not yet publicly responded to the court’s decision. Settlement does not seem very likely. An “opt-in” settlement agreement accomplishes very little for Google because Google can, and already has, continue to make private agreements with publishers and authors. Many of us hope that Google will approach Congress to pass copyright reform, such as this legislation that stalled out in Congress in 2008.

While Congress is the appropriate forum for addressing the issue–and not a far-reaching agreement between corporations and private parties–Congress is notorious for leaving the crafting of copyright legislation to large, wealthy, corporate copyright holders. The voices of libraries, the public, and people who make use of public domain materials, are typically ignored. So although I have been hoping for the settlement to be rejected so that Congress can tackle the problem, there are some serious barriers to its passing. Google will propose legislation very similar to the ASA, except the Registry will be government run and the ability to exploit orphan works will be opened up to other entities. Companies like Amazon and Microsoft will not like this because Google has a head start on commercializing orphan works. Congress will ignore provisions meant to assist libraries in digitizing their collections or helping patrons gain access to orphan and out-of-print works. Is there any way to make arguments in support of a robust public domain palatable to Congress?