The growing usage of apps meant it was only a matter of time until they would find their way into legal education. Following up on a previously published article on LaaS – Law as a Service, this post discusses different ways that apps can be included into the law degree curriculum.

1 Changing legal education through the use of apps

There are different ways in which apps can be used in legal education in order to better prepare students for the legal profession. In this post we suggest three different possibilities for the usage of apps, reflecting different pedagogical styles and learning outcomes. What each of the suggestions has in common is to bring legal education closer to the real-life work of lawyers.

Through identifying aspects in which we perceive legal education as lacking quality or quantity, we apply and implement these to our suggestions for changed legal education. The aspects we view as lacking are: identifying and managing risks, the interaction between different areas of law, and proactive problem-based learning. To take each of these briefly in turn:

- managing risks is something that practicing lawyers and other legal service professionals must do on a daily basis. Law is not only about applying legal rules but also about weighing options, estimating possible outcomes and deciding upon which risks to accept. Legal education has not traditionally included this in the curriculum, and students have arguably very little experience of such training in their studies.

- interaction between different areas of law is often hard to incorporate in legal studies, which follow a block or module structure. Each course provides students with in-depth knowledge of that particular legal area. However, the interaction between such modules is lacking, with teachers often unaware of the content of preceding or succeeding courses. For students, a problem with this module structure can be that they forget the content of a course studied at an earlier stage in their education.

- problem-based learning is generally encouraged and applied in legal education. However, most problem-based learning (PBL) is reactive, asking students to evaluate the legal consequences of a scenario that has already played out, instead of training students purely in after-the-fact solutions, in other words “clearing up the legal mess.” PBL should be made more proactive, aiming to train students in identifying and counteracting problems before they arise. This can also be viewed as an implementation of the first aspect, managing risks.

In aiming to include these aspects in legal education, we view technology as playing an important role. Perhaps ideally, the whole legal education could be re-structured in order to include such practical aspects that reflect the current legal profession; however, such change is perhaps too complex and viewed as somewhat unnecessary by those who are able to make such changes – if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, as the saying goes. An app is not necessarily the sole possible implementation method, but it serves as an example of how these aspects can relatively easily be brought within legal education.

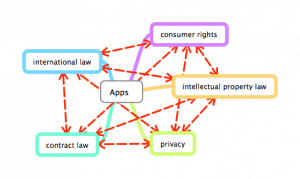

The first teaching approach looks at legal aspects of apps themselves, where the apps are viewed as objects within law. Here students are provided with a set problem and are encouraged to consider how different areas of law may apply to the app in question, and how the various areas impact on each other. This approach implements both PBL and the interaction of different legal fields. Proactiveness may also be included by asking students to identify legal risks of the app, and how such risks could by reduced through the use of law.

The second approach brings together technology and law, and is as such a suitable suggestion for inclusion in a legal informatics course, or as part of more general jurisprudence. Students are given the task of developing a legal service app, and thus must implement law through a technological tool. Students must first identify a need for a service within an area of law of their choosing, and then develop an app which provides the service. This approach implements both PBL and proactiveness, and can also require students to consider both legal and technical risks.

The third approach aims to add value to the legal education as a whole, by making available an app to students to be used alongside teaching, complementing the existing education. Students are provided with the opportunity to test their knowledge, and combine different areas of study through interactive learning. Depending on the design of the app, this approach has the possibility of implementing all aspects: PBL, interaction of legal fields, and proactiveness or risk management.

2 Legal aspects of apps

Legal education in many countries around the world is set up as linear blocks of different legal fields and subject areas.  As law is often divided into various sub-fields–such as private law, public law, administrative law, environmental law, or information technology law–it appears only natural to discuss and teach the subjects one by one. The amount of material to be learned by the student would otherwise be overwhelming. While in some countries, exams might encompass multiple fields of law, subjects are being taught in a consecutive order.

As law is often divided into various sub-fields–such as private law, public law, administrative law, environmental law, or information technology law–it appears only natural to discuss and teach the subjects one by one. The amount of material to be learned by the student would otherwise be overwhelming. While in some countries, exams might encompass multiple fields of law, subjects are being taught in a consecutive order.

Though the pedagogical reasons for the linearity in legal education are convincing, some improvements are still possible. One idea that we would like to discuss here are legal aspects of apps that intertwine different legal fields and challenge the students to analyze one particular phenomena from various different legal angles. We are not suggesting any particular fora for this exercise; these might stretch from traditional in-class seminars to online e-learning platforms to a mixture of the two and be included in law school curricula either as compulsory or selective modules.

Apps and information communication technologies, in general, do not adhere to geographical, physical or time related boundaries. They inherently challenge the traditional legal system based on bricks and mortar. In this regard they are, therefore, well-suited for legal analysis.

Another reason to use apps as the object for analysis by students is their popularity among the younger (and older) generation and therefore the close relationship students have to them to start with. As an example, one can compare it to using Facebook when discussing privacy, as opposed to showing a large company’s employee database.

In order to reflect the real-life experience of the exercise even more, the students would be allocated a certain expert area. As at law firms, one student would be an expert in intellectual property rights, another in contract law, another in privacy, international law, consumer rights issues, etc.

The students would –from the perspective of their expert area–firstly investigate possible legal issues with a specific gaming app, for example. They would analyze the application of the rules and norms within their field and identify potential conflicts or loopholes within these rules. Their investigation would include testing the app itself, as well as looking at possible end-user agreements and other applicable contractual agreements between the user, the app store and the developer of the app.

The next step would be to identify and discuss possible overlaps, discrepancies and conflicts between the different areas of law in relation to the app. The exercise should result in a written and/or oral report of the different legal issues involved and solutions to potential conflicts between the law and the app.

Adding another layer of real-life scenario, each group could be asked to present their findings to an imaginative client who is the producer of the app. This simulation would allow the students not only to develop a legal analysis based on correlating fields of law but also to present the analysis to non-lawyers, translating legal jargon into understandable everyday language.

The exercise–analyzing an existing app–very much fits into the idea often conveyed in legal education that law is applied after an incident occurs. In order to add a level of proactivity, students could be asked to analyze an app under production, before it is launched. This would guarantee more proactive thinking by the students asking them to foresee potential conflicts and avoid them, rather than discussing legal issues after they have arisen.

While the exercise as such might not be a revolutionary idea, we think that the increased inclusion of such exercises in legal education would contribute to better preparation of students for their life as young lawyers.

3 Law’s implementation in apps

While the previous exercise fits well within the traditional legal education by asking students to deliver a legal analysis, a topic less discussed in undergraduate legal studies is how to employ technology for delivering law. With a few exceptions, students generally focus on analyzing the law rather than implementing law in technology.

Until several years ago legal analysis was the main business for lawyers, so legal education well reflected the profession. In the last few years, however, legal services delivered via and as technology have increased and opened up a new market for lawyers and legal professionals. This change should be reflected in legal education in order to prepare students for their future.

While the idea is not to replace lawyers with apps or software, an app or another technology could either help lawyers in their working tasks or deliver law as a valuable service for consumers, citizens, companies or organizations. Examples of such apps, both for lawyers and end-users, are mentioned in a post at iinek’s blog and Slaw; shorter lists can be found on iinek’s Delicious page and the iPad4lawyers blog.

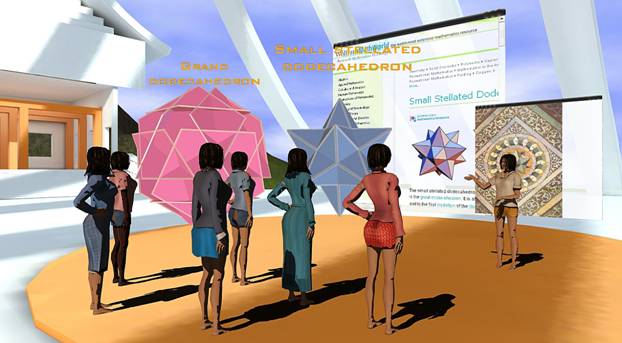

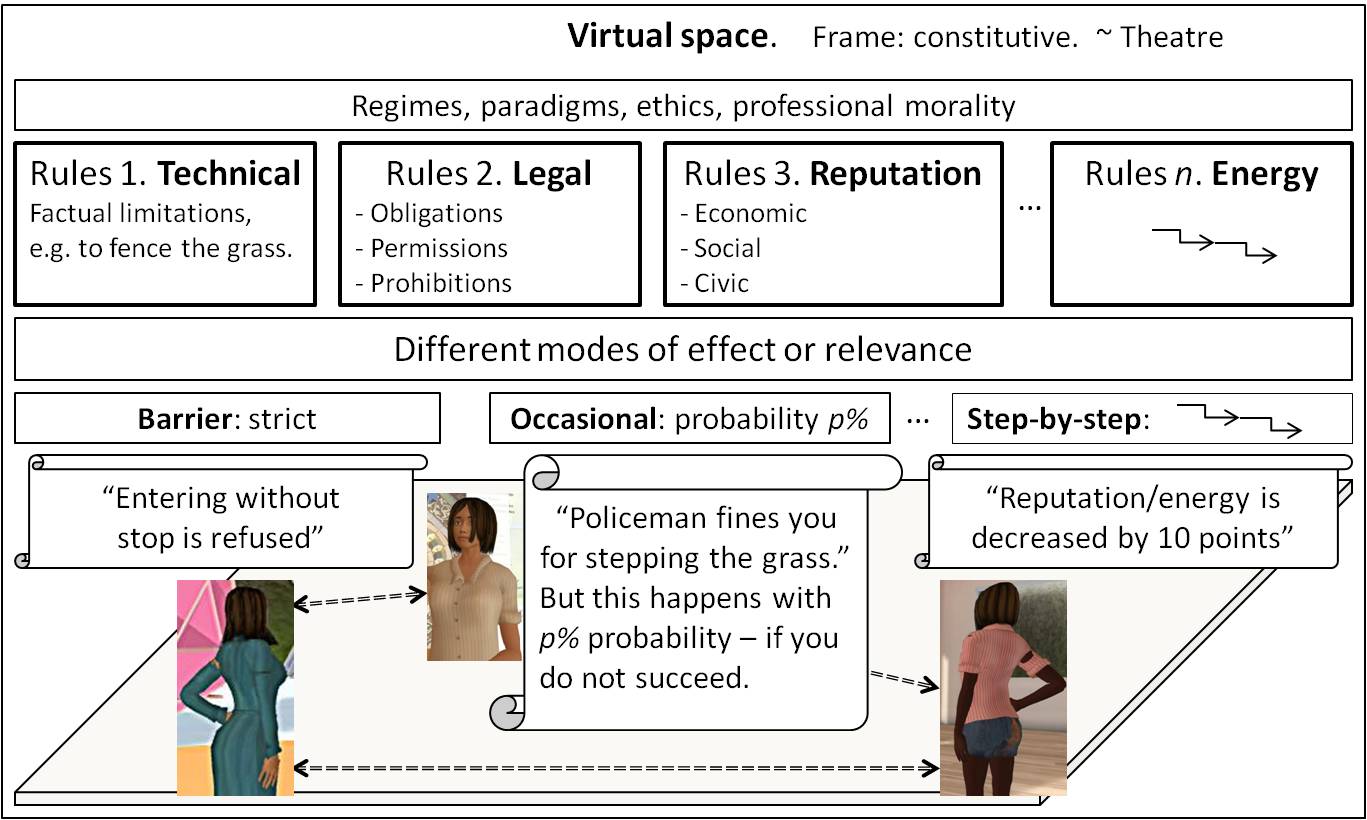

In the exercise, students would look at law from a different perspective, i.e. how legal regulations affect the individual or organization. Going away from a linear text approach, students would have to translate law into a format that users or apps can read. In other words, law would have to suit the user/app, and not the other way around. Students would, therefore, have to go beyond text and translate rules into flowcharts, diagrams, mind maps and other visual tools in order for the app to be able to follow the law’s instructions.

Implementing legal rules into technology, therefore, not only encourages students to think proactively but it also motivates them to identify solutions for the application of the law and how rules could be transformed into practice. From a pedagogical point of view the exercise would allow the students to think about different aspects of law beyond the traditional case or contract. It would also encourage a wider viewpoint of law as a tool in society.

Again, how the exercise is included in the curriculum is a matter of taste. Technical assistance is of importance, in order for students to know what aspects to take into account and what schematics developers need in order to be able to create an app. The exercise could be set up as a competition (Georgetown Law School – Iron Tech Lawyer) with an expert jury consisting of practicing lawyers and developers.

4 Legal education as an app

Talking about legal education as an app can have different meanings. While legal apps (for lawyers and individuals) and educational apps are rather common these days, legal educational apps are not so developed, yet.

Legal education, as mentioned, is traditionally taught in blocks or modules, with very few references and links between them. This setup clearly has its benefits, not least logistically. There are clear arguments in favor of such an approach; planning and studying becomes easier for teachers and students alike, time limitations mean that implementing an approach that makes connections between each subject is hard. This is where we believe that technology has the potential to play an important role. Technology is not bound to physical classrooms and attendance requirements of students or teachers. It has the ability to be accessed at a time of the student’s choosing, without placing additional demands on instructors.

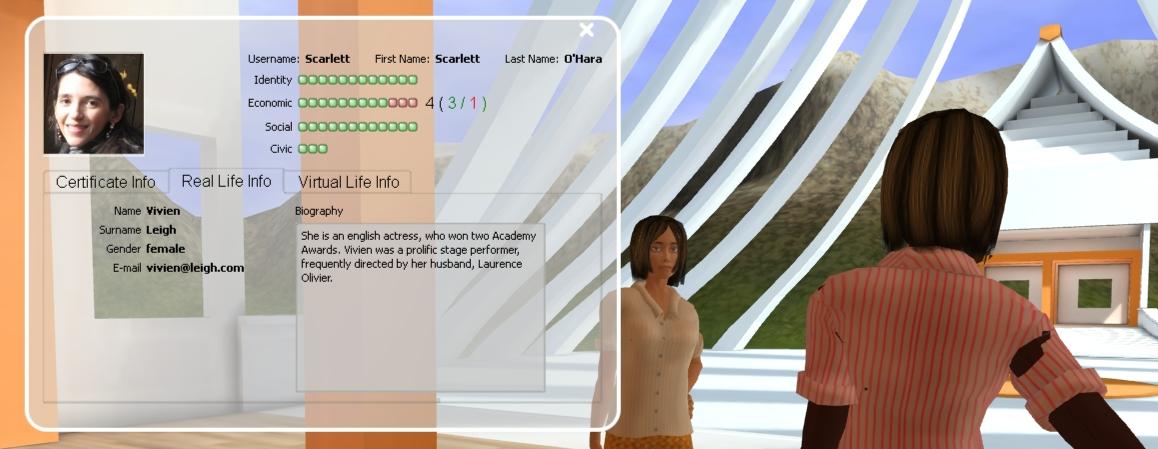

A legal education app could provide the key in aiding students to make connections between their study areas; it could be made to fit alongside a law degree, assuming a student’s knowledge in sync with their level of study, by including content from both current and past courses. The app would offer an easy way to implement an interactive, problem-based learning approach. It could provide additional content, quizzes, exercises, social media functions etc. complementing the education and enabling a holistic perspective.

Although no teacher-student relationship is required here, clearly pedagogical thinking would need to play a strong role so that a worthwhile learning environment for the individual could be created. Much time and effort would need to be invested in planning, and the application itself would need to be flexible to adjust to different study plans and so forth. Another issue is, of course, who would make the app. As curricula vary from law school to law school, and jurisdiction to jurisdiction, such an app is ideally built by those who know the curriculum. Such “in-house” expertise also means that potential bias from outside factors should be avoided.

Legal apps have already been introduced to help lawyers study for qualifying exams, e.g. BarMax. (These are often, however, still very topic-specific.) Implementing the same kind of thinking at the educational level would start to prepare students for their future workplace, allowing them to be better prepared for helping clients with real-world scenarios dealing with complex and interrelating legal issues. If students begin such thinking at the beginning of their legal studies, it becomes normal, arguably allowing for better educated graduates.

This last approach is perhaps a little future-oriented (although not as much as, for example, grading by technology), and it is of course not easy to implement at the university level; academics must work together with app developers to produce a tool of real value to students. However, even a slimmed-down version of such an app can be a tool for helping students prepare for exams, test their knowledge of legal areas, or simply make sure that they have understood concepts covered in teaching. Some examples of such implementations in legal education are shown here.

5 Conclusions

There is no doubt that apps are the future for legal services. To what extent they will be included in legal education is yet to be decided. Here we have shown three differing approaches that could help in this regard. Implementation of any or all of these would bring in aspects that are currently lacking in legal education.

Rather often discussions on technology and legal education focus on e-learning and online teaching environments. In our opinion, traditional offline exercises and their pedagogical value should not be underestimated, with technology offering an excellent platform as an object, tool or companion during legal education and life as a lawyer.

6 Sources

- Christine Kirchberger & Pam Storr, LaaS – Law as a Service, Lov&Data Nr. 4/2011

- Christine Kirchberger & Pam Storr, blog post Law as a Service?, Blawblaw, 30 March 2012

- Christine Kirchberger, blog post Law as an app, 25 January 2012

- Jason Wilson; I Am Now an App™; Slaw, 28 September 2011

- John Markoff, Armies of Expensive Lawyers, Replaced by Cheaper Software, New York Times, 4 March 2011

- Caroline Strevens, Christine Welch & Roger Welch; On-line legal services and the changing legal market: preparing law undergraduates for the future; The Law Teacher, 45:3, 2011, 328–347

- Marc Bousquet, Robots Are Grading Your Papers!, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 18 April 2012

Christine Kirchberger is a doctoral candidate & lecturer in legal informatics at the Swedish Law and Informatics Research Institute (IRI). Her research focuses on legal information retrieval, the concept of legal information within the framework of the doctrine of legal sources and also examines the information-seeking behaviour of lawyers. Christine blogs at iinek.wordpress.com and can be found as @iinek on Twitter.

Christine Kirchberger is a doctoral candidate & lecturer in legal informatics at the Swedish Law and Informatics Research Institute (IRI). Her research focuses on legal information retrieval, the concept of legal information within the framework of the doctrine of legal sources and also examines the information-seeking behaviour of lawyers. Christine blogs at iinek.wordpress.com and can be found as @iinek on Twitter.

Pam Storr is a lecturer at the Swedish Law and Informatics Research Institute (IRI), and course director for the Master Programme in Law and Information Technology at Stockholm University. Her main areas of interest are within information technology and intellectual property law. Pam is the editor for IRI’s blog, Blawblaw, and can be found as @pamstorr on Twitter.

Pam Storr is a lecturer at the Swedish Law and Informatics Research Institute (IRI), and course director for the Master Programme in Law and Information Technology at Stockholm University. Her main areas of interest are within information technology and intellectual property law. Pam is the editor for IRI’s blog, Blawblaw, and can be found as @pamstorr on Twitter.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed. The information above should not be considered legal advice. If you require legal representation, please consult a lawyer.

Vytautas Čyras

Vytautas Čyras