Professor Richard Leiter, on his blog, The Life of Books, poses The 21st Century Law Library Conundrum: Free Law and Paying to Understand It:

The digital revolution, that once upon a time promised free access to legal materials, will deliver on that promise; it’s just that the free materials it will deliver, even if it comprises the sum total of all primary law in the country at every level and jurisdiction, will amount to only a minor portion of the materials that lawyers need in order to practice law, and the public needs in order to understand it.

This article explores what more we need in order to understand the law and how this need can be met, from a UK perspective.

Free acce ss to law

ss to law

Free access to primary law is of course a prerequisite for the interpretation and understanding of the law. In the UK and most countries with a common law tradition, the cause of free access to law is espoused by the Free Access to Law Movement, a collective of legal information institutes that began with the creation of the Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute (LII) in 1992. In the UK we are represented by the British and Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII), set up in 2000 with the enormous help of the pioneering Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII). In October 2002, at the 4th Law via Internet Conference in Montreal, the LIIs published a joint statement of their philosophy of access to law in the following terms:

Legal information institutes of the world, meeting in Montreal, declare that,

- Public legal information from all countries and international institutions is part of the common heritage of humanity. Maximising access to this information promotes justice and the rule of law;

- Public legal information is digital common property and should be accessible to all on a non-profit basis and free of charge;

- Independent non-profit organisations have the right to publish public legal information and the government bodies that create or control that information should provide access to it so that it can be published.

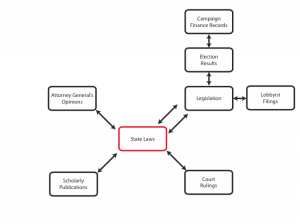

So, to paraphrase liberally, we have a right to access the laws of our land, free of charge and openly licensed. “The problem for aggregators like LII,” Leiter points out, “is that the information that they provide is only as good as the sources available to them. And governments are just not very good sources of their own information.” In the US, Law.Gov is a movement working to raise the quality of government information, proposing a distributed repository of all primary legal materials of the United States. It believes that “the primary legal materials of the United States are the raw materials of our democracy. They should be made more broadly available to enable an informed citizenry,” and that “governmental institutions should make these materials available in bulk as distributed, authenticated, well-formatted data.” In other words, we need more than free access to law; we need free access to good law data.

UK legislation

In the UK we were fortunate that the previous administration’s Power of Information agenda was being implemented by the Office of Public Sector Information (OPSI), whose role also includes that of Queen’s Printer (of legislation). In December 2006, the long-awaited Statute Law Database (SLD) had been published, having been more than 10 years in development. This provided (subject to a number of shortcomings) point-in-time access to all in-force UK primary legislation since the year dot (forever), and access to all secondary legislation published since 1991. Responsibility for the SLD then lay with the Statutory Publications Office (SPO), part of the Ministry of Justice. In 2008 the decision was taken to merge the SPO into OPSI, who had been publishing all as-enacted legislation since 1988. The merger would bring the online legislative services together, creating a single place where visitors could access the widest range of legislative content held by the government, alongside supporting material. That service is Legislation.gov.uk, launched in July 2010, which has now replaced the SLD and OPSI legislation services.

The Legislation.gov.uk interface provides simple and direct browse access to legislation by type, year and number, and simple or advanced searches to locate matching legislation. Primary legislation can be viewed as at any point in time since 1991. More important than this improved access to legislation, however, is the fact that the content is open. It is all well-structured XML; any piece of legislation or legislation fragment can be addressed reliably and simply in various useful formats via the URI scheme; and any list of legislation resulting from a query can be delivered as an Atom feed. And a new licensing model for public sector information (which in the UK is subject to Crown copyright) was introduced at the same time – the Open Government Licence.

Unfortunately, there are insufficient government resources to maintain an up-to-date, consolidated statute book, as Shane O’Neill observes:

The lack of up-to-date consolidation – no fault of the Legislation.gov.uk team who have laboured valiantly on their Sisyphean task – must be a concern to those who harboured greater ambitions (not least Government and judiciary). It leaves access to an up-to-date and consolidated statute book in the hands of those who have invested in and deliver highly exclusive legal information services [Westlaw/LexisNexis – hereafter Wexis].

The Legislation.gov.uk service is delivered by The National Archives (of which OPSI is part) with John Sheridan, Head of e-Services and Strategy, at the helm. John describes the development in some detail in an earlier post on VoxPopuLII:

We had two objectives with legislation.gov.uk: to deliver a high quality public service for people who need to consult, cite, and use legislation on the Web; and to expose the UK’s Statute Book as data, for people to take, use, and re-use for whatever purpose or application they wish.

There’s more about the technical project and the people behind it from Jeni Tennison, technical lead and main developer (at TSO), on her blog. John is also on the expert panel of technologists advising the government on making public sector information more open and accessible on the Web, an initiative which led to the development of data.gov.uk, which currently provides access to over 5,600 central government datasets.

UK case law

Unfortunately, the public provision of case law in the UK is woefully inadequate, and we have to rely on the efforts of BAILII (a charity) to collate and deliver anything approaching a comprehensive collection of recent judgments. BAILII does a grand job in the circumstances, but – through no fault on its part – it is not comprehensive and it is not open. The various courts all publish their judgments in their own fashion, with no consistency of approach; in fact the High Court of England and Wales does not publish its own judgments at all, but passes selected handed-down judgments to BAILII to publish. To make matters worse, our right to access this case law is far from clear. There is some argument whether judges are public servants or not and hence whether their judgments are public sector information or not. In addition, regarding older judgments, the low level of originality required for copyright protection in the UK means that almost all older cases are copyright of either the transcriber or the reporter (or the publisher who commissioned them).

Understanding the law

Does free access to law or, even better, free access to good law data, make the law accessible? Will it empower the average citizen? Unfortunately not. As Leiter says, it is only a fraction of what lawyers need to practice law and the public needs to understand it. The law is not practically accessible: it is difficult to identify, obtain and understand legal resources, and they are frequently out of date. Whilst it is reasonable to expect legal advisers to invest in the necessary commercial services to inform themselves, these services are becoming increasingly unaffordable for the less affluent law practices and third sector advice bodies. For the non-lawyer, the law is all but impenetrable, and solving many legal problems and resolving disputes is in practice affordable only to the rich or those who are eligible for some kind of state support. Lord Justice Toulson in R v Chambers [2008] EWCA Crim 2467 famously bemoaned the complexity of legislation:

To a worryingly large extent, statutory law is not practically accessible today, even to the courts whose constitutional duty it is to interpret and enforce it. There are four principal reasons. … First, the majority of legislation is secondary legislation. …Secondly, the volume of legislation has increased very greatly over the last 40 years …Thirdly, on many subjects the legislation cannot be found in a single place, but in a patchwork of primary and secondary legislation. … Fourthly, there is no comprehensive statute law database with hyperlinks which would enable an intelligent person, by using a search engine, to find out all the legislation on a particular topic.

The give-us-the-data-and-we’ll-organise-the-world crowd also display a touching naïvety when it comes to the law. For example, on the launch of Legal Opinions on Google Scholar, Anurag Acharya, “Distinguished Engineer” at Google, said:

We think this addition to Google Scholar will empower the average citizen by helping everyone learn more about the laws that govern us all. … we were struck by how readable and accessible these opinions are. Court opinions don’t just describe a decision but also present the reasons that support the decision. In doing so, they explain the intricacies of law in the context of real-life situations.

Any initiative that makes the law more accessible is to be welcomed, but to empower the average citizen you have to go the extra mile, by explaining the law. Lawyers and legal researchers have spent years learning the law and acquiring the skills that enable them to navigate and reliably interpret primary law and precedent. They will find value in free access to law and in Google Scholar and other free services that are built on that, but they and the average citizen need more. That need is met largely by commercial publishers, and, while there many smaller independent publishers who provide good value in their niches, as O’Neill observes:

Legal publishing has long been dominated by two huge duopolists (Reed Elsevier’s LexisNexis and ThomsonReuters) whose scale alone enables them to provide a consolidation of the mix of primary, secondary, case law which characterises our common law system. This has created what [barrister Francis Davey] in The Times on 23 May 2006 characterised as “a two-tier justice system with only the very rich able to access the full consolidated law while those lawyers doing pro bono work are discriminated against.”

But there is an increasing amount of quality free legal commentary and analysis on the Web, and we can dream on.

The law wiki dream

Writing in Times Online in April 2006, the eminent Professor Richard Susskind, legal tech guru and adviser to the great and good, spelt out his vision for a “Wikipedia of English law”:

This online resource could be established and maintained collectively by the legal profession; by practitioners, judges, academics and voluntary workers. If leaders in the English legal world are serious about promoting the jurisdiction as world class, here is a genuine opportunity to pioneer, to excel, to provide a wonderful social service, and to leave a substantial legacy. The initiative would evolve a corpus of English law like no other: a resource readily available to lawyers and lay people; a free web of inter-linked materials; packed with scholarly analysis and commentary, supplemented by useful guidance and procedure; rendered intensely practical by the addition of action points and standard documents; and underpinned by direct access to legislation and case law, made available by the Government, perhaps through BAILII. … A Wikipedia of English law could be an evolving, interactive, multimedia legal resource of unprecedented scale and utility.

Susskind referred specifically to wikis and “a Wikipedia,” and that was taken rather literally by those who enthusiastically first took up his challenge. But I don’t believe he necessarily intended it literally, and I don’t believe that “a Wikipedia” or indeed the wiki platform is appropriate. Wikipedia has to be seen as a one-off; no wiki project since has come anywhere near its scale or success. We are most unlikely to build an encyclopedia of UK law from scratch; but why would we try when there is already a vast free legal web?

The free legal web

In 2008, enthused by the developments in open government and by the amount of quality legal commentary that was percolating up on the Web, I proposed to set up a service to exploit this – FreeLegalWeb. In the manifesto I listed the free access law resources then available, and I now list them with appropriate updates, here:

- We have [free and open access to legislation]

- [We have] other official documents, forms and guidance from government and a commitment to making these resources more accessible and encouraging user generated services.

- We have another substantial free access primary law database – BAILII.

- We have a number of specialists already maintaining specialist law wikis and enthusiasts contributing law articles to Wikipedia.

- We have a growing number of law bloggers, many of whom provide succinct, expert ongoing commentary and analysis.

- We have many other individuals, firms and publishers who publish case summaries, articles, updaters and guidance for free access on their websites.

- We have public, charitable and private services providing free guidance and fora for the public faced with legal processes.

- And finally, we have Web 2.0 technologies that enable (potentially) all these sources to be interrogated, aggregated, “mashed up” and repurposed.

That sounded like a free legal web to me; all we had to do was join it up and curate it! But how feasible is that?

A “bunch of goo”?

Bob Berring, legal research guru and Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley, gave his thoughts on the matter  on YouTube in October 2009. He believes that government efforts in the provision of free legal information have failed because there are no incentives; and that “volunteer efforts”, worthy as they may be, are unlikely to be sustained. He rightly says that legal information is not easily packaged: we need a map and a compass to navigate it; it needs to be organised and value added. I think we all agree with that. But his conclusion appears to be that only Wexis have sufficient incentive and only they can mobilise the necessary army to add sufficient value for it to be useful. For Bob, the free legal information that’s out there is “a bunch of goo,” and the only thing that can sort out the mess is “the market system”. That’s clearly not the case:

on YouTube in October 2009. He believes that government efforts in the provision of free legal information have failed because there are no incentives; and that “volunteer efforts”, worthy as they may be, are unlikely to be sustained. He rightly says that legal information is not easily packaged: we need a map and a compass to navigate it; it needs to be organised and value added. I think we all agree with that. But his conclusion appears to be that only Wexis have sufficient incentive and only they can mobilise the necessary army to add sufficient value for it to be useful. For Bob, the free legal information that’s out there is “a bunch of goo,” and the only thing that can sort out the mess is “the market system”. That’s clearly not the case:

- government has an incentive to make legal information more accessible

- the legal profession has an incentive to make legal information more accessible

- various non-profits have an incentive to make legal information more accessible

- citizens have an incentive to make legal information more accessible

- and there are many private enterprises short of Wexis who have an incentive to make legal information more accessible.

… How?

Curating the legal web

For help I’m increasingly turning to Jason Wilson, Vice President at Jones McClure Publishing. He has a nice clean minimalist blog with great pics accompanying each post. More importantly, he’s interested in the kind of questions I’m also trying to answer, such as: Can we crowdsource reliable analytical legal content?

I have given considerable thought to this problem (and I have a greater interest in solving it than most), and I just don’t see how a Demand Media or similar model could ever produce good or reliable analytical material.

But in the next breath he acknowledges that a lot of good stuff has indeed already been generated by the crowds, and asks how we will organise that legal web. Actually the question is buried at the end of a dense post about “exploded data” (the value of analytical content):

My thought at this point is that the legal web is in an infancy that we can’t even fathom yet. There is cloud of associated information that our current computer assisted legal research vendors cannot give to us based on their algorithms, especially when they remain in walled-in gardens that don’t account for the vast and valuable information being created by users. The question is whether we will step up to organize this sea of data, or wait until a program can do it for us?

Moving on, in a more accessible post on Slaw he asks how we can effectively curate the legal web:

Curating this growing body of analytical content will be difficult. It suggests a person-machine process of locating and separating good content from bad, and categorizing, verifying, authenticating, and editorializing that content. It will undoubtedly require the creation of a rich taxonomy to help organize and manage the content for later discovery, clean metadata, and a good search engine, and raises issues from data permanency to copyrights to brand dilution. It’s a mess. But a worthy one I think.

and in the comments to that post:

I suppose the point to my post is whether we can wrap a wiki-like structure and interface around the legal web, and make it a destination for learning about both general topics and specific issues, rather than just a portal for all results that match search terms.

Yes we can! However clever the machine, these tasks – “locating and separating good content from bad, and categorizing, verifying, authenticating, and editorializing” – to a large degree require human intervention. But that intervention need only be light touch once we figure out how most effectively to harness the wisdom of the crowds.

Conclusion

Free access to law is not a panacea, but there is plenty of scope for delivering more accessible law by leveraging not just free law but the free legal web; for delivering free services that are good enough for the average citizen, and for lower cost commercial services that are good enough for the average lawyer. Big Law will continue to need Wexis, but the “lower-tier” can be much better served. The final word I will leave with Tom Bruce:

We need to make informed choices between inexpensive automated approaches that work by brute force and the hand-crafted, highly-accurate approaches of legal bibliography that are not always scalable or affordable. We need to recalibrate what we mean by “authority”, and begin to think about measures of quality and reliability for legal text that avoid the creation of unnatural monopolies in legal information.

[Editor’s Note: For more information on crowdsourcing legal commentary, please see Staffan Malmgren’s post. On using social media to enhance access to free legal resources, see Olivier Charbonneau’s post. On making primary law useable by non-lawyer citizens, see earlier posts by Judge Dory Reiling and Christine Kirchberger. For earlier replies to Bob Berring, see Tom Bruce’s responses here and here.]

Nick Holmes is a publishing consultant specialising in the UK legal sector and is Managing Director of legal information services company infolaw (infolaw.co.uk). He is also the founder of FreeLegalWeb CIC (freelegalweb.org).

Nick Holmes is a publishing consultant specialising in the UK legal sector and is Managing Director of legal information services company infolaw (infolaw.co.uk). He is also the founder of FreeLegalWeb CIC (freelegalweb.org).

Email: nickholmes [at] infolaw [dot] co [dot] uk. Twitter: @nickholmes.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor in chief is Robert Richards.

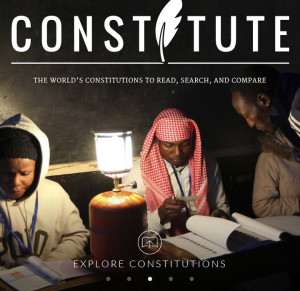

Two years ago my collaborators and I introduced a new resource for understanding constitutions. We call it Constitute. It’s a web application that allows users to extract excerpts of constitutional text, by topic, for nearly every constitution in the world currently in force. One of our goals is to shed some of the drudgery associated with reading legal text. Unlike credit card contracts, Constitutions were meant for reading (and by non-lawyers). We have updated the site again, just in time for summer (See below). Curl up in your favorite retreat with Constitute this summer and tell us what you think.

Two years ago my collaborators and I introduced a new resource for understanding constitutions. We call it Constitute. It’s a web application that allows users to extract excerpts of constitutional text, by topic, for nearly every constitution in the world currently in force. One of our goals is to shed some of the drudgery associated with reading legal text. Unlike credit card contracts, Constitutions were meant for reading (and by non-lawyers). We have updated the site again, just in time for summer (See below). Curl up in your favorite retreat with Constitute this summer and tell us what you think. (with some evidence) that readers strongly prefer to read constitutions in their native language. Thus, with a nod to the constitutional activity borne of the Arab Spring, we have introduced a fully functioning Arabic version of the site, which includes a subset of Constitute’s texts. Thanks here to our partners at International IDEA, who provided valuable intellectual and material resources.

(with some evidence) that readers strongly prefer to read constitutions in their native language. Thus, with a nod to the constitutional activity borne of the Arab Spring, we have introduced a fully functioning Arabic version of the site, which includes a subset of Constitute’s texts. Thanks here to our partners at International IDEA, who provided valuable intellectual and material resources.