The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.

– Henry VI, Pt. 2, Act 4, sc. 2.

This line, delivered by Dick the Butcher (turned revolutionary) in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, is often performed tongue-in-cheek by actors to elicit an expected laugh from the audience. The essence of the line, however, is no joke, and relates to destabilizing the rule of law by removing its agents — those who promote and enforce the law. What no one could predict, including Shakespeare himself, is the horrific precision with which such a deed could be carried out.

The 1994 Genocide in Rwanda showed this horror and more, with upwards of one million killed in the span of three months. The effect on the legal system was particularly devastating, with the targeting of lawyers and the justice sector, resulting in the targeted killing of prosecutors and judges at its outset.

Rwanda’s Justice Sector Development

Since 1994, Rwanda has done a remarkable job rebuilding its society, establishing security, curbing corruption, and creating one of the fastest growing economies in sub-Saharan Africa.

One of the biggest areas of development in Rwanda, and in other areas of the world, has been strengthening justice sector institutions and strengthening the rule of law. In transitional states, especially those developing systems of democratic governance, the creation of online, reliable, and accessible legal information systems is a critical component of good governance. Rwanda’s efforts and opportunities for development in this area are noted below.

From 2010-2011, I played a very small part of this development when I served as a law clerk and legal advisor to then-Chief Justice Aloysie Cyanzayire of the Supreme Court of Rwanda. Working with a USAID-funded project, I was also able to participate with legal education reform, and the development of an online database of laws, the Rwanda Legal Information Portal (RwandaLIP). In the summer of 2013 I returned to Rwanda, with the support of the American Association of Law Libraries, to visit its law libraries and understand the role of law libraries in legal institutions and overall society. After learning the Rwanda LIP was no longer updated (and now offline entirely), investigating Rwanda’s online legal presence became a secondary research goal for the trip. The discovery also highlighted the importance of legal information systems and their role in justice sector reform. Part of this justice sector reform related to changes in Rwanda’s legal system. Once a Belgian colony, at independence Rwanda inherited a civil law system, codified much of the Belgian civil code, and today the main body of laws comes from enactments of Parliament. Rwanda’s judicial system, rebuilt after the 1994 Genocide, is made up of four levels of courts: District Courts, Provincial Courts, High Courts, and the Supreme Court.

With its civil law roots, courts in Rwanda were largely unconcerned with precedent. As Rwanda became a member of the East African Community in 2007 (and adopted English as an official language), the judiciary started a transition to a hybrid common law system, considering how to assign precedential value to court decisions. With this ongoing transition in Rwanda’s legal system, an online legal information system has become a significant need for legal and civil society.

One of four computer labs, called the “digital library” at Kigali Independent University, with more than 400 computer workstations available for student use.

Online Legal Information Systems

In order to establish the rule of law in a democratic system, citizens must have access, at the very minimum, to laws of a government. To make this access meaningful, a searchable database of laws should be created to allow users of legal information to find laws based on their particular information need. For this reason alone it is important for governments in transitional states to make a commitment to developing online legal information systems.

John Palfrey aptly noted: “In most countries, primary legal information is broadly accessible in one format or another, but it is rarely made accessible online in a stable and reliable format.” This is basically the case in Rwanda. Every law library, university library, and even the Kigali Public Library have paper copies of the Official Journal — the official laws of Rwanda. Today, however, the only current place to find laws online is through the Prime Minister’s webpage, where PDF copies of the Official Gazette are published. The website Amategeko.net (Kinyarwanda for “law”) was frequently used by lawyers and members of the justice sector to search Rwanda’s laws, and allowed the general public to not only access laws, but run a full text search for keywords. This site, however, was not updated after 2011, and is now completely offline. The result is no online source to search Rwanda’s laws.

Rwanda is using its growing information infrastructure, however, to create other online quasi-legal information databases. For instance, the Rwanda Development Board created an online portal for businesses to access information on “investment related procedures” in Rwanda. The government is also allowing online registration of businesses, streamlining the processes and making it more accessible. These developments make sense with Rwanda’s reforms in the area of economic development, and its recent ranking in the top 30% globally for ease of doing business, and 3rd best in sub-Saharan Africa. While economic reform has driven these changes, justice sector reform has not yet yielded the same results for online legal information systems.

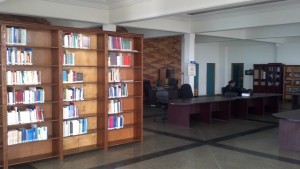

Service counter at the University Library at Kigali Independent University in Rwanda. Students aren’t allowed to browse the library stacks.

Rwanda’s Legal Information Culture Despite the limited online access to laws, there is a high value placed on legal information in Rwanda. Every legal institution has a law library and a dedicated library staff member (although most don’t have formal education in librarianship or information management). Moreover, members of the justice sector, from staff members to Permanent Secretaries and Ministers, believe libraries and access to legal information is of critical importance. A common theme in Rwanda’s law libraries, however, is the lack of funding. Some libraries have not invested in library materials in years, and have solely relied on donations to add items to their collections. It is not altogether surprising, then, that the Rwanda LIP remained un-funded, and is now completely defunct as an online legal information system. One source close to the Rwanda LIP project indicated that funding has been sought at Parliament, but as of today has yet to be successful.

The failure of the Rwanda LIP is perhaps a victim of how it came to be; that is, through donor-funded development. Creating sustainable online databases requires a government commitment of financial support. Just as Amategeko.net before it, the Rwanda LIP was created through a donor-funded initiative, and at its conclusion the LIP’s source of funding also ended. For any donor-funded development initiative, sustainability is a key concern, and significant government collaboration is necessary for initiatives to remain after donor-funded projects end. This concept is especially true with legal information systems, and is perhaps the cause for the Rwanda LIP’s demise. While created in partnership with the Government of Rwanda, it failed to adequately secure a commitment for continued funding at its outset. Sustainability issues are not unique to Rwanda’s experience with online legal information systems. The availability of financial resources is one of the key challenges to creating a sustainable online database of laws. Working with developing countries in Africa, SAFLII found that sustainability issues come from “shortages of resources, skills and technical services.” While donor-funded projects have serious limitations, others experiencing the sustainability challenge have suggested databases supported by private enterprise, “offering free content as well as value-added services for sale.” One thing for certain is that long-term sustainability remains one of the biggest challenges for online legal information systems.

Print to Digital Transition and Overcoming the Digital Divide In addition to sustainability, transition from print to digital poses its own complications, and has emerged as a major issue in law libraries, from even the most established institutions. This challenge is especially unique in the context of developing and transitional states, where access to the internet can pose a significant challenge. This problem, known as the “digital divide,” has been described as something that “disproportionately disenfranchises certain segments of society and runs counter to the notion that inclusiveness and opportunity build strong communities and countries.” This is an even larger problem in developing and transitional states, where there is far less wealth and technological infrastructure for internet connectivity, and a greater disparity in access between and among communities.

Of all countries in the process of developing online legal information systems, however, Rwanda is perhaps the best suited to succeed. With high-speed fibre-optic internet cables recently installed throughout the small East African country, Rwanda has one of the best internet penetration rates in the developing world. So, while Rwanda’s law libraries (and other libraries) throughout the country have print copies of laws, there may be a legitimate opportunity to give a large number of citizens online access. For example, the Kigali Public Library, the flagship institution of the Rwanda Library Services, houses print copies of the laws of Rwanda but also has an internet cafe giving free access to online resources. Kigali Independent University has an “Internet Library” with more than 500 computers for student use. Rwanda’s law libraries are also open and accessible to the public, some of which have computers for use by the public as well. Other libraries, including the law library at the National University of Rwanda, have increasing access to online resources to serve their users.

In Rwanda, a new access to information law (Official Gazette No. 10 of 11.03.2013) makes online legal information even more critical in the developing state, and Rwanda’s current efforts can serve as an example for the importance of modernizing online legal information. The access to information law imposes a positive obligation on the Government of Rwanda, and some private companies working under government contracts, to disclose a broad range of information to the public and press. It has been stated that the law “meets standards of best practice in terms of scope and application” for freedom of information laws. Despite the law’s conditions to withhold information under Article 4, the significant shift in policy and the law’s broad range of information available are very positive signs. This and similar laws across the developing world have created a need for the improvement of existing legal information systems, or the creation of new systems to adequately make available essential legal information. A critical component to the implementation of this law, therefore, is a reliable and sustainable online legal information system.

Lessons Learned from Rwanda’s Experience

While Amategeko.net and the Rwanda LIP are no longer online, institutions within the justice sector of Rwanda are currently working on solutions. In the meantime, there is no meaningful way to search Rwanda’s laws online. It is possible that a stronger financial commitment at the outset of the Rwanda LIP would have solved this. In the future, long-term sustainability should be one of the primary qualifications for creating an online system.

In the meantime, there are other ways of expanding Rwanda’s access to online legal information through databases of foreign law and secondary sources. Talking with law librarians in Rwanda, I learned that there is little, if any research instruction being delivered from law libraries. Even in the few libraries with subscription electronic databases, users aren’t necessarily being directed to relevant legal resources. Furthermore, law librarians generally collect, catalog and retrieve legal materials for users, rather than directing users to relevant sources. Users of legal information in Rwanda (and elsewhere) would be well served by being exposed to other online sources of legal information. Sites like the LII, WorldLII, and the Directory of Open Access Journals offers access to a wealth of free online primary and secondary materials that could be useful to researchers. Creating research guides and offering research instruction in these areas costs very little, and opens up countless resources that could be valuable to users of legal information in Rwanda, and elsewhere. Those working in justice sector development should investigate the possibility for this, in conjunction with creating online legal information systems of domestic laws.

Finally, the majority of those working as librarians in Rwanda’s law libraries have no formal instruction in library or information science. Nonetheless, it is remarkable that those with little or no formal training are competent librarians. Formal training or not, qualified librarians generally do not have the opportunity to offer research training to users of legal information. Treating law librarians as professionals would open up many opportunities to increase the capacity of users of legal information, and the online resources available.

Brian Anderson is a Reference Librarian and Assistant Professor at the Taggart Law Library at Ohio Northern University. His research involves the use of law libraries and legal information systems to support the rule of law in developing and transitional states. In September 2013 Brian presented two papers at the 2013 Law Via the Internet conference related to this topic; one related to civil society organizations and the use of the internet to strengthen the rule of law, and another about starting online legal information systems from scratch.

Brian Anderson is a Reference Librarian and Assistant Professor at the Taggart Law Library at Ohio Northern University. His research involves the use of law libraries and legal information systems to support the rule of law in developing and transitional states. In September 2013 Brian presented two papers at the 2013 Law Via the Internet conference related to this topic; one related to civil society organizations and the use of the internet to strengthen the rule of law, and another about starting online legal information systems from scratch.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.

Benjamin Keele is a reference librarian at the

Benjamin Keele is a reference librarian at the  As I said, the lorises move slowly. Glacially, even. I mean, I’m talking sloooooooow. Why is that? Well, they don’t have a physical impediment keeping them that way. Nor should it be assumed that they are lazy or have some other character defect (as if one could assign character defects to wild animals.) As a matter of fact, when they choose to catch live prey they can move quite quickly. They operate this way because when one is creeping along small jungle branches high in the air in the middle of the night and not running from any particular predator, it pays off to take one’s time and be cautious.

As I said, the lorises move slowly. Glacially, even. I mean, I’m talking sloooooooow. Why is that? Well, they don’t have a physical impediment keeping them that way. Nor should it be assumed that they are lazy or have some other character defect (as if one could assign character defects to wild animals.) As a matter of fact, when they choose to catch live prey they can move quite quickly. They operate this way because when one is creeping along small jungle branches high in the air in the middle of the night and not running from any particular predator, it pays off to take one’s time and be cautious. So instead I say, “Get in the goddamn wagon or get out of the goddamn way.” I imagine at times the ride will be about as comfortable and collegial as a bunch of children crammed in a station wagon for a family vacation road trip. There is no ultimate “Mother” authority to keep us all in line with the threat of turning around, however. For these collaborative efforts to be successful, no constituency or person gets to be “in charge” all the time. It doesn’t matter how many millions of dollars in grant money one has, or how many thousands of members in one’s organization; everyone’s expertise needs to be used and respected. It won’t be easy and it won’t feel natural, but we all must make a conscious effort to work together.

So instead I say, “Get in the goddamn wagon or get out of the goddamn way.” I imagine at times the ride will be about as comfortable and collegial as a bunch of children crammed in a station wagon for a family vacation road trip. There is no ultimate “Mother” authority to keep us all in line with the threat of turning around, however. For these collaborative efforts to be successful, no constituency or person gets to be “in charge” all the time. It doesn’t matter how many millions of dollars in grant money one has, or how many thousands of members in one’s organization; everyone’s expertise needs to be used and respected. It won’t be easy and it won’t feel natural, but we all must make a conscious effort to work together. It’s been a rocky year for West’s relationship with law librarians.

It’s been a rocky year for West’s relationship with law librarians. I often compare these annual feature introductions to the evolution of automobile engines, thanks to a childhood spent watching my father work on the family cars. At first Dad knew every nook and cranny of our vehicles, and there was little he couldn’t repair himself over the course of a few nights. As we traded in cars for newer models, his job became more difficult as engines became more complex. None of the automakers seemed to consider ease of access when adding new parts to an automobile engine. They were simply slapped on top of the existing ones, making it harder to perform simple tasks, like replacing belts or spark plugs.

I often compare these annual feature introductions to the evolution of automobile engines, thanks to a childhood spent watching my father work on the family cars. At first Dad knew every nook and cranny of our vehicles, and there was little he couldn’t repair himself over the course of a few nights. As we traded in cars for newer models, his job became more difficult as engines became more complex. None of the automakers seemed to consider ease of access when adding new parts to an automobile engine. They were simply slapped on top of the existing ones, making it harder to perform simple tasks, like replacing belts or spark plugs. For an assignment in one of my legal research classes this semester, I provided a fact pattern and asked students to perform a Natural Language search in Westlaw of American Law Reports to find a relevant annotation. In a class of only 19 students, six of them answered with citations to resources other than ALR, including articles from American Jurisprudence, Am.Jur. Proof of Facts, and Shepards’ Causes of Action. The problem, it turned out, wasn’t that they had searched the wrong database. Every one of them searched ALR correctly, but those six students mistook Westlaw’s Results Plus, placed at the top of a sidebar on the results page, for their actual search results. Filter failure, indeed.

For an assignment in one of my legal research classes this semester, I provided a fact pattern and asked students to perform a Natural Language search in Westlaw of American Law Reports to find a relevant annotation. In a class of only 19 students, six of them answered with citations to resources other than ALR, including articles from American Jurisprudence, Am.Jur. Proof of Facts, and Shepards’ Causes of Action. The problem, it turned out, wasn’t that they had searched the wrong database. Every one of them searched ALR correctly, but those six students mistook Westlaw’s Results Plus, placed at the top of a sidebar on the results page, for their actual search results. Filter failure, indeed. There is evidence that the companies have the expertise to provide a better user experience. West has

There is evidence that the companies have the expertise to provide a better user experience. West has  Tom Boone is a reference librarian and adjunct professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. He’s also webmaster and a contributing editor for

Tom Boone is a reference librarian and adjunct professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. He’s also webmaster and a contributing editor for  These days, anyone with a pulse can sign up for a free

These days, anyone with a pulse can sign up for a free  law libraries. Do they provide us with satisfactory methods of evaluating the quality of our libraries? Do they offer satisfactory methods for comparing and ranking libraries? The data we gather is rooted in an old model of the law library where collections could be measured in volumes, and that number was accepted as the basis for comparing library collections.

law libraries. Do they provide us with satisfactory methods of evaluating the quality of our libraries? Do they offer satisfactory methods for comparing and ranking libraries? The data we gather is rooted in an old model of the law library where collections could be measured in volumes, and that number was accepted as the basis for comparing library collections.

Stephanie Davidson is Head of Public Services at the University of Illinois in Champaign. Her research addresses public services in the academic law library, and understanding patron needs and expectations. She is currently preparing a qualitative study of the information behavior of legal scholars.

Stephanie Davidson is Head of Public Services at the University of Illinois in Champaign. Her research addresses public services in the academic law library, and understanding patron needs and expectations. She is currently preparing a qualitative study of the information behavior of legal scholars.