Most legal publishers, both free and fee, are primarily concerned with content. Regardless of whether they are academic or corporate entities providing electronic access to monographs, the free providers of the world giving primary source access, Westlaw or Lexis (hereinafter Wexis) providing access to both primary and secondary sources, or any other legal information deliverer, content has ruled the day. The focus has remained on the information in the database. The content. The words themselves.

If trends remain stable, primary source content, at least among politically stable jurisdictions, will be a given. Everyone will have equal access to the laws, regulations, and court decisions of their country online. In the U.S., new free open source access points are emerging every day. Here, the public currently has their choice of LII, Justia, Public Library of Law, AltLaw, FindLaw, PreCYdent, and most recently, OpenJurist, to discover the law. And hopefully, that content will be official and authentic.

The issue then refocuses to secondary sources and user interfaces. These will be where the battle lines will be drawn among legal publishers. Both assist in making meaning out of primary sources, though in fundamentally different ways. Secondary sources explain, analyze, and provide commentary on the law. They can be highly academic and esoteric, or provide nuts and bolts instructions and guidance. They also include finding aids to primary sources, like annotations to statutes, indexes, headnotes, citator services, and the like. While access to government-produced primary sources is a right, access to secondary sources is not, although for lay persons and lawyers alike, primary sources alone are typically insufficient to fully understand the law. I leave the not insignificant issue secondary sources for another day, and focus here on content access and the user interface.

“The eye is the best way for the brain to understand the world around us.”

— Quote reported identically by multiple users on Twitter from a recent talk by Dr. Ben Shneiderman at the #nycupa.

Despite the advances made in adding legal online content, equal attention has not been given to how users may optimally access that content to fulfill their information-seeking needs. We continue to use the same basic Boolean search parameters that we have used for nearly fifty years. We continue to presume that sorting through search result lists is the best way to find information. We continue to presume that research is simply a matter of finding the right keywords and plugging them into a search box. We presume wrong. Even though keyword searching is beloved by many because it provides the illusion of working, it consistently fails.

There is, in fact, another method of finding information that is inherently contextual, and that educates the user contemporaneously with the discovery process. This method is called browsing. Wexis, through their user interfaces, encourage searching over browsing because they are profit centers whose essential product is the search. It is commonly assumed that their product is the database, i.e. the content, because they negotiate access to specific databases with their customers. And while some databases are worth more than others, they charge by the number of searches, not by the number of documents retrieved, not by the amount of content extracted. (This describes the transactional costs, which are probably most frequently employed. Of course, the per search charge varies by database. Users may alternately choose to be charged by time instead. )

Therefore, their profits are maximized by creating a search product that is not too good and not too bad. They are, in fact, rewarded for their search mediocrity. If it is too good, users will find what they need too quickly, decreasing the number of searches and amount of time spent researching, and profits will decline. If it is too bad, users will get frustrated, complain, and, perhaps eventually, try a different vendor. Though with our current two-party system, there is little real choice for legal professionals who have sophisticated legal research needs not satisfied by the open access options available. (And then there is the distasteful possibility that law firms themselves want to keep legal research costs inflated to serve as their own profit centers.)

As such, Wexis will not be optimally motivated to improve their user interfaces and enhance the information-seeking process to increase efficiency for their customers. This leaves the door wide open for others in the online legal information ecology to innovate and force needed change, create a better product themselves, and apply pressure on the Ferraris and Lamborghinis of the legal world to do the same.

“A picture is worth a thousand words. An interface is worth a thousand pictures.”

— Quote reported identically by multiple users on Twitter from a recent talk by Dr. Ben Shneiderman at the #nycupa.

The time is ripe to create a new information discovery paradigm for legal materials based on semantics. Outside the legal world, advances are being made in more contextual information discovery platforms. Instead of a user issuing keywords and a computer server spitting back results, adjusting input via trial and error ad infinitum, graphic interfaces allow the user to comprehend and adjust their conception and results visually with related parameters. These interfaces encourage an environment where research is more like a conversation between the researcher and the data, rather than dueling monologues.

Lee Rainie, Director of the Pew Internet & American Life Project, recently discussed the emerging information literacies relevant to the evolving online ecology. These literacies should inform how search engines adapt themselves to human needs. Their application in the legal world is a natural fit. Four literacies most applicable to legal research include:

• Graphic Literacy. People think visually and process data better with visual representations of information. Translation: make database interfaces and search results graphic.

• Navigation Literacy. People have to maneuver online information in a disorganized nonlinear text screen. This creates comprehension and memory problems. We want our lawyers and legal researchers to have good comprehension and memory when serving clients.

• Skepticism Literacy. Normally referring to basic critical thinking skills, this should apply to critically assessing user interfaces, particularly in a profit-seeking environment like Wexis where the interface can affect how and what you search, as well as your wallet.

• Context Literacy. People need to see connections both between and within information in a hyperlinked environment. Simply providing hyperlinks is good, but graphically visualizing the connections is better.

Some subscription databases and internet search features serve these literacies well. Many of these are in early stages and not necessarily fit for legal research, but can give an idea of possibilities. I’ll discuss a few, and consider how these might apply in the legal context.

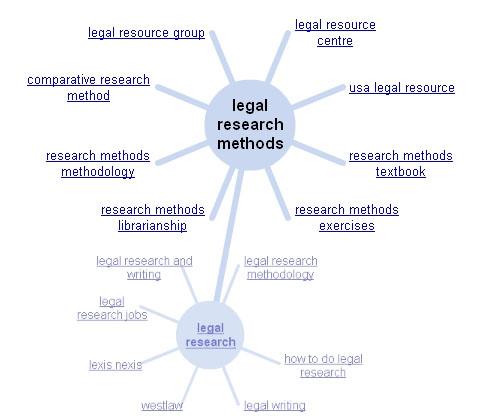

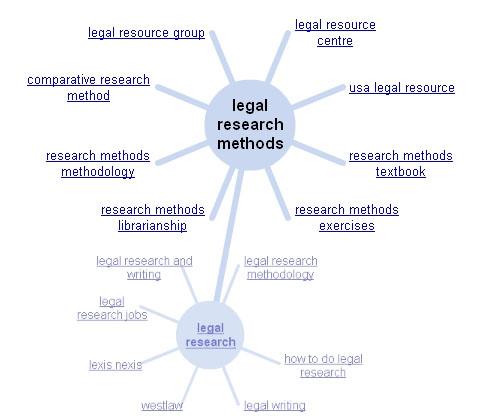

Google has recently re-released their wonder wheel which helps users figure out what they are looking for. This is a frequent stumbling block for novices to legal research, and even for seasoned attorneys faced with a new subject. The researcher simply doesn’t know enough to know what exactly to look for. A tool like this helps the researcher find terms and concepts that they might not have otherwise considered (of course, secondary sources are excellent for this as well). Pictured here, the small faded hub at the bottom was for my original search of “legal research.” I then clicked on the “legal research methodology” spoke which expanded above the first wheel with different spokes and further ideas.

Google has recently re-released their wonder wheel which helps users figure out what they are looking for. This is a frequent stumbling block for novices to legal research, and even for seasoned attorneys faced with a new subject. The researcher simply doesn’t know enough to know what exactly to look for. A tool like this helps the researcher find terms and concepts that they might not have otherwise considered (of course, secondary sources are excellent for this as well). Pictured here, the small faded hub at the bottom was for my original search of “legal research.” I then clicked on the “legal research methodology” spoke which expanded above the first wheel with different spokes and further ideas.

A common problem with keyword searching is finding the right words in the correct combination that exemplify a concept and are not over or under inclusive. Wexis offers thesauri which can be helpful, though they require actual searching to test. Some free sites, like PreCYdent, have this feature as well. They work to greater and lesser degrees. A recent search for “Title VII sex retaliation” resulted in a suggestion to also search for Title III, which is clearly not my intended subject. And while helpful, thesauri and other word and concept suggestors are still tied to the search paradigm which we want to move away from.

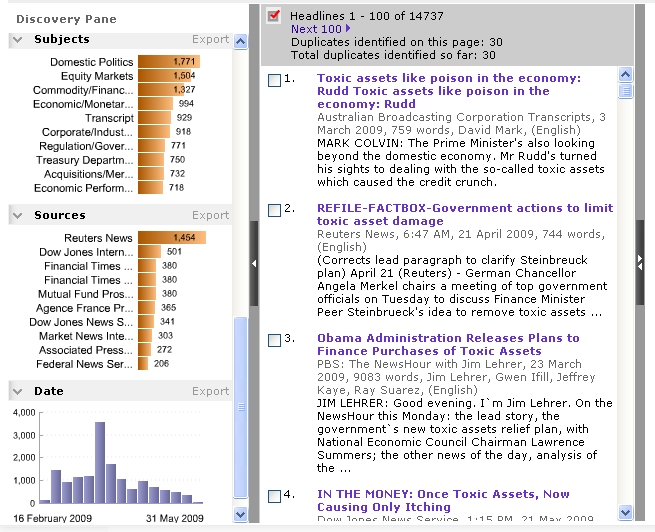

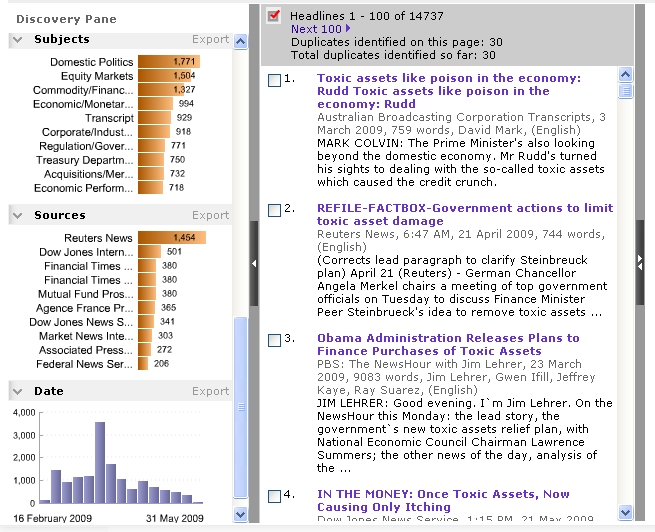

Factiva is a subscription database provider supplying news and business information. It provides a graphical “discovery pane” with “intelligent indexing” that clusters results by subjects related to search terms. This allows the user to select the most relevant results to their purpose. It also features word clouds (not pictured here) with text size indicating prominence of these terms in search results. Date graphs indicate when search results were published, so the user can visually assess when a topic is most frequently covered in the news.

Factiva is a subscription database provider supplying news and business information. It provides a graphical “discovery pane” with “intelligent indexing” that clusters results by subjects related to search terms. This allows the user to select the most relevant results to their purpose. It also features word clouds (not pictured here) with text size indicating prominence of these terms in search results. Date graphs indicate when search results were published, so the user can visually assess when a topic is most frequently covered in the news.

Subject-based indexing is an excellent contextual tool to guide the user to relevant content without searching. Legal context literacy is supported by indexes to subject-based compilations, such as statutes and regulations. It’s great to have the full text of statutes available for free online, but some kind of subject-based entry port to that collection is needed to render it maximally useful. For databases like these, given the non-natural language used by legislators and lobbyists alike in constructing laws, keyword searching is frequently an inefficient and frustrating discovery method. Currently, Westlaw is the only legal information provider that provides online subject indexing to state and federal codes (though they like to hide that fact in their interface because their product is the search, not the content).

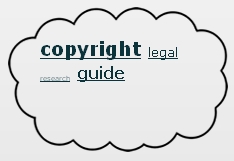

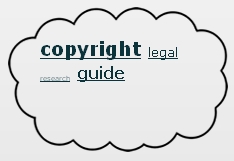

Weighting words, graphically represented by the size of the term, is another method users can employ to improve their results with keyword searching. Factiva uses weighted word clouds to indicate the frequency of terms in search results. SearchCloud allows users to manually weight search terms to indicate their importance within the search and adjusts results accordingly. For example, a researcher may need to find documents with five different words in them, but three are essential in symbolizing the idea sought, and the other two are needed, but not as important. As pictured here, I searched for copyright legal research guides, giving most importance to the words copyright and guide, and less to the words legal and research to ensure that I retrieved guides on copyright and not just any list of research guides that might mention copyright, and that it was in fact a legal research guide and not some other document that just mentions the word guide. Results were significantly more relevant here than the same un-weighted search on Google.

Weighting words, graphically represented by the size of the term, is another method users can employ to improve their results with keyword searching. Factiva uses weighted word clouds to indicate the frequency of terms in search results. SearchCloud allows users to manually weight search terms to indicate their importance within the search and adjusts results accordingly. For example, a researcher may need to find documents with five different words in them, but three are essential in symbolizing the idea sought, and the other two are needed, but not as important. As pictured here, I searched for copyright legal research guides, giving most importance to the words copyright and guide, and less to the words legal and research to ensure that I retrieved guides on copyright and not just any list of research guides that might mention copyright, and that it was in fact a legal research guide and not some other document that just mentions the word guide. Results were significantly more relevant here than the same un-weighted search on Google.

Weighted words can easily be employed in legal research. For example, with case law search results and citator reports, instead of a list of cases and other documents arranged either by date, jurisdiction, or algorithmic relevancy, citator information can be graphically indicated. Cases that are cited the most would appear near the top of the list in the largest fonts. Cases cited the least would appear in a smaller font at the bottom of the list. It adds immediate meaning-making visual cues to an otherwise non-contextual list, letting the researcher know at a glance which are the most important cases.

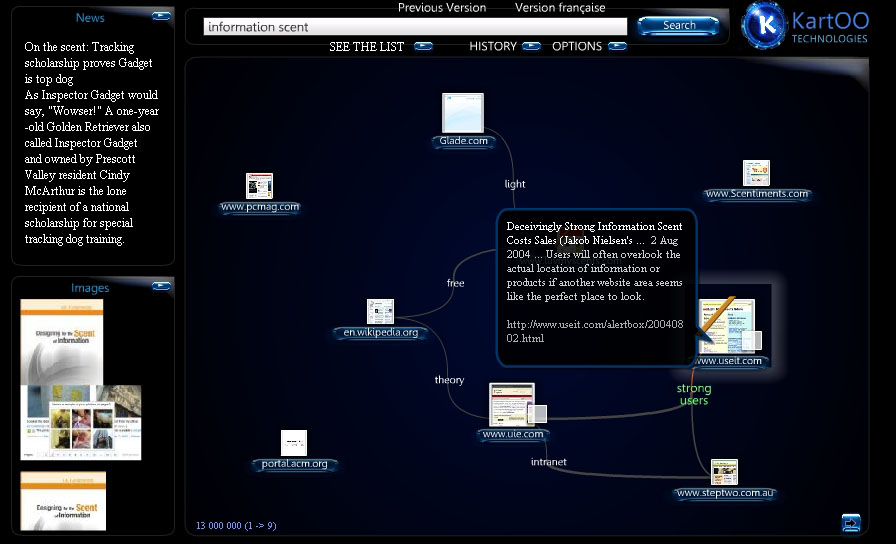

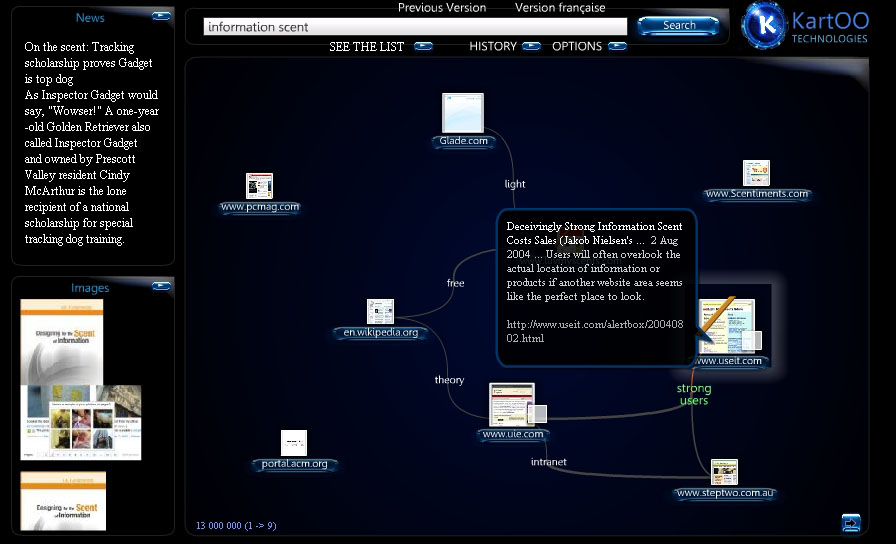

It would be a boon to researchers if the connection between results was made apparent graphically.  KartOO attempts this with their search engine which links various web pages in results with associated terms and similar pages. Mousing over links allows the user a preliminary peek at the search result to further determine its relevancy. The benefits to lawyers for this type of graphic display of search results for cases could be enormous. To be able to tell at a glance how a body of law is interconnected would give immeasurable context and meaning to what would otherwise be a simple list, each result visually disconnected from the other.

KartOO attempts this with their search engine which links various web pages in results with associated terms and similar pages. Mousing over links allows the user a preliminary peek at the search result to further determine its relevancy. The benefits to lawyers for this type of graphic display of search results for cases could be enormous. To be able to tell at a glance how a body of law is interconnected would give immeasurable context and meaning to what would otherwise be a simple list, each result visually disconnected from the other.

Some type of contextual map like the wonder wheel or a concept chart like KartOO, potentially combined with weighted words, could be employed that would illustrate the interconnectedness between all the cites to the case at issue, or to search results of cases. The biggest, most precedential, most frequently inter-cited cases would live near the center of the web with large hubs, less important cases would live at the peripheries. Most cases are never cited and are jurisprudentially less significant. This should be made clear through visual cues. Westlaw just launched something similar for patents.

These are just a few examples, based on developing technology, of how the legal search paradigm might develop. The beauty of our legal corpus is its fundamental interconnectedness. The web of cites within and between documents gives semantic developers a preconstructed map of relevancy and importance so that they need only create a way to symbolize that pattern graphically.

“Semantics rule, keywords drool.”

— Quote at twitter.com/scagliarini. See also http://www.expertsystem.net/blog/?p=68.

The future of legal information discovery interfaces combines searching and browsing, text and context, graphics and metadata. Because content without meaning thwarts understanding. Laws without context do not serve democracy. We need “interactive discovery.” Which is why search result lists are dead to me.

Julie Jones, formerly a librarian at the Cornell Law School, is the “rising” Associate Director for Library Services at the University of Connecticut Law School, beginning later this month. She received her J.D. from Northwestern University School of Law, M.L.I.S. from Dominican University, and B.A. from U.C. Santa Barbara.

Julie Jones, formerly a librarian at the Cornell Law School, is the “rising” Associate Director for Library Services at the University of Connecticut Law School, beginning later this month. She received her J.D. from Northwestern University School of Law, M.L.I.S. from Dominican University, and B.A. from U.C. Santa Barbara.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt

.

![]() When Michael Foucault argued that Bentham’s Panoptic structures had become essential to the functioning of a modern secular state, he did not claim originality for the insight.

When Michael Foucault argued that Bentham’s Panoptic structures had become essential to the functioning of a modern secular state, he did not claim originality for the insight.

Google has recently re-released their

Google has recently re-released their  Factiva

Factiva

As a comparative law academic, I have had an interest in legal translation for some time. I’m not alone. In our

As a comparative law academic, I have had an interest in legal translation for some time. I’m not alone. In our  Frank Bennett

Frank Bennett

On the 30th and 31st of October 2008, the 9th International Conference on “

On the 30th and 31st of October 2008, the 9th International Conference on “ Ginevra Peruginelli

Ginevra Peruginelli Enrico Francesconi

Enrico Francesconi