In this post I describe the process and requirements that eventually led to the MetaLex Document Server, a server that hosts all versions of Dutch national statutes and regulations published since May 2011, both as CEN MetaLex, and as Linked Data. Before I set out to do so, however, I would like to emphasize that, although the development of the server and its contents was a one-man-job, the road to make it possible surely was not solitary. A couple of people I’d like to mention here are Alexander Boer, Radboud Winkels, and Tom van Engers of the Leibniz Center for Law, together with whom I have worked over the past ten years to develop, test, and publish the ideas that underlie CEN MetaLex. Also, the team around legislation.gov.uk clearly has done a lot of great and inspiring work in this area.

In this post I describe the process and requirements that eventually led to the MetaLex Document Server, a server that hosts all versions of Dutch national statutes and regulations published since May 2011, both as CEN MetaLex, and as Linked Data. Before I set out to do so, however, I would like to emphasize that, although the development of the server and its contents was a one-man-job, the road to make it possible surely was not solitary. A couple of people I’d like to mention here are Alexander Boer, Radboud Winkels, and Tom van Engers of the Leibniz Center for Law, together with whom I have worked over the past ten years to develop, test, and publish the ideas that underlie CEN MetaLex. Also, the team around legislation.gov.uk clearly has done a lot of great and inspiring work in this area.

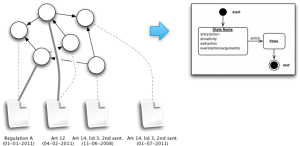

So, what happened? Over the course of last spring, I was involved in several small-scale projects that shared a specific need: version-aware identifiers for all parts of legislative texts. The first of these was a report for the Swiss Federal Chancellery on possible technological solutions for a regulation drafting system to be used by the Swiss government. Second to arrive on my desk was a project for the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration (Belastingdienst), in which we were asked to develop a concept-extraction toolkit that would allow them to make explicit where concepts are defined, where they are reused, and how they relate to other concepts (e.g., from an external thesaurus). The purpose of this project was to investigate whether we could replace with technology what is currently a manual process of turning legislation into business processes that fuel citizen- and business-oriented services. The Belastingdienst needs this to better cope with the yearly changes to tax regulation issued by the Ministry of Finance. The Dutch Immigration and Naturalisation Service (IND) faces exactly the same problem: of discovering what part of their business processes is affected by each legislative modification. Updates to legislation require continuous, significant investment in IT re-engineering.

The root of the problem

But don’t modern European governments already have elaborate facilities for supporting this workflow? I’m afraid not.

Currently, regulation drafting is a process of sending around Word documents, copy-and-pasting from older texts, “version hell,” signing by a Minister, and sending the enacted regulations off to a publisher, who will then turn it into some XML format to feed a publishing platform to generate HTML, PDF, and paper versions of the texts. This process is not designed with a content management perspective, and most if not all metadata is thrown away in the process.

Part of the problem is one of organisational change: convincing legislative drafters to use a more structured approach in their daily work. The Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice is currently developing a legislative editing environment (similar to the MetaVex editor developed at the University of Amsterdam), but it will take awhile before this is adopted in practice.

Requirements

To develop a chain of tools for managing legal information, both as text and as knowledge models, we need to address a number of key requirements:

- An integrated legislative drafting and editing environment that supports advanced version and provenance tracking (e.g., version tracking of successive changes to draft texts). Provenance information is very important for eliciting the procedure that led to an official version (both pre- and post-publication), as well as its underlying motivation.

- A format in which these texts are stored that is flexible enough to allow both editing and publication to various formats (such as PDF and HTML).

- The ability to persistently identify every element of a legal text. Versioning of texts, references, and metadata requires identifiers that reflect the different versions of these resources. The various parts of a text should be versioned independently, allowing for transitory regimes.

A versioning mechanism should distinguish between a regulation text as it exists at a particular time, and the final regulation. The IFLA Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) (Saur, ’98) makes the following distinctions: the work as a “distinguishable intellectual or artistic creation” (e.g., the constitution); the expression as the “intellectual or artistic form that a work takes each time it is realised” (e.g., “The Constitution of July 15th, 2008”); the manifestation as the “physical embodiment of an expression of a work” (e.g., a PDF version of “The Constitution of July 15th, 2008”); and the item as a “single exemplar of a manifestation” (e.g., the PDF version of “The Constitution of July 15th, 2008” residing on my USB stick).

- These identifiers should be dereferenceable to the element they describe, or a description of the element’s metadata.

- Metadata and annotations should be traceable to the most detailed part of a text, as well as to its version, when needed. The same requirement holds for references between texts, allowing for fine-grained analysis of interdependencies between texts.

- It is furthermore a requirement that these identifiers be transparent and follow a prescribed naming convention. This allows third parties to construct valid identifiers without having to first query a name service.

- The metadata itself should be made accessible in a standard format as well.

Making do with what we’ve got

As we don’t have any time to waste, and have neither the organisational infrastructure, nor the funds, to use or develop any other (richer) information source, we need to make do with what’s currently available. How hard is it to build a chain of tools that meets at least part of these requirements? And, what information does the Dutch government already provide on which we can build the services that it itself so dearly needs?

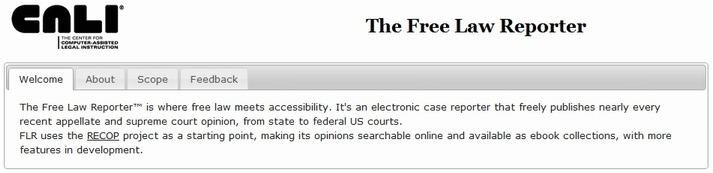

![]()

Wetten.overheid.nl is the de facto source for legislative information in The Netherlands. Users can perform a full text search through the titles and text of all statutes and regulations of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. They can search for a specific article, as well as for the version of a text as it stood at a specified date. Wetten.overheid.nl also provides an API for retrieving XML manifestations of statutes and regulations.

Identifiers

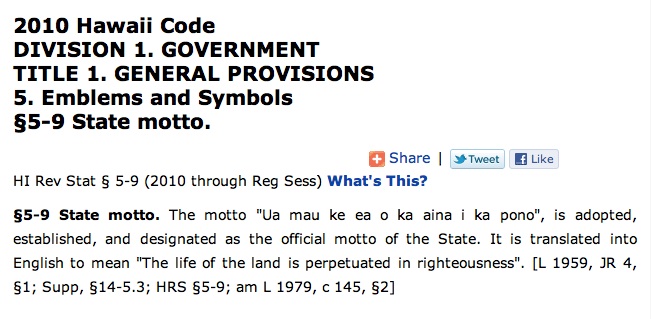

What about identifiers? Wetten.nl supports deeplinks to particular versions of statutes and regulations, but is not very consistent about it. For example:

http://wetten.overheid.nl/cgi-bin/deeplink/law1/bwbid=BWBR0005416/article=6/date=2005-01-14

and

both point to article 6 of the Municipal law, as it was in effect on January 14th, 2005. A third mechanism for identifying regulations is the Juriconnect standard for referring to parts of statutes and regulations. XML documents hosted by Wetten.nl use these identifiers to specify citations between statutes and regulations. For instance, the Juriconnect identifier for article 6 of the Municipal law is:

1.0:c:BWBR0005416&artikel=16&g=2005-01-14

But… the standard does not prescribe a mechanism for dereferenecing an identifier to the actual text of (part of) a statute or regulation.

The BWB XML service and format

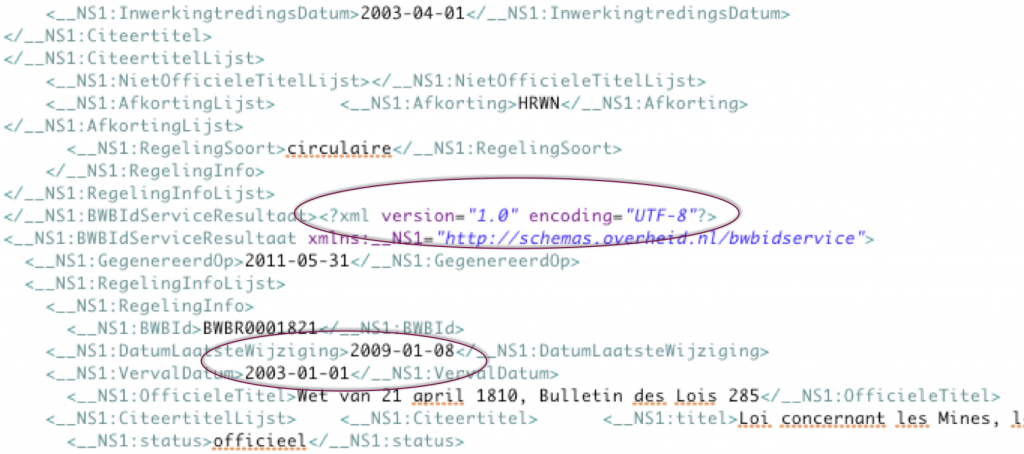

XML manifestations of statutes and regulations are retrievable through an API on top of the “Basiswettenbestand” (BWB) content management system. This REST Web service only provides the latest version of an entire statute or regulation. The BWB XML document returned is stripped of all version history: it does not even contain the version date of the text itself.

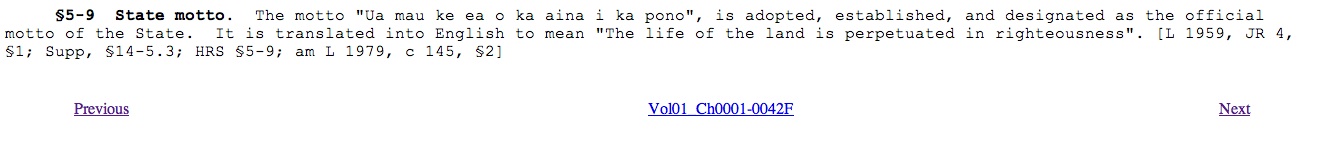

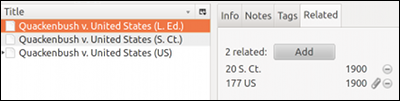

An index of all BWB identifiers, with basic attributes such as official and abbreviated titles, enactment and publication dates, retroactivity, etc. is available as a zipped XML dump or a SOAP service. Unfortunately, the XML file is corrupt, and the date of the latest change to a statute or regulation reported in the index is not really the date of the latest modification, but of the latest update of the statute or regulation in the CMS. See the picture above.

The BWB uses its own XML schema for storing statutes and regulations; this schema does not allow for intermixing with any third-party elements or attributes, ruling out obvious extensions for rich annotations such as RDFa. And, BWB XML elements do not carry any identifiers.

A more general XML format: CEN MetaLex

CEN MetaLex is a jurisdiction-independent XML format for representing, publishing, and interchanging legal texts. It was developed to allow traceability of legal knowledge representations to their original source. MetaLex elements are purely structural. Syntactic elements (structure) are strictly distinct from the meaning of elements by specifying for each element a name and its content model. What this essentially does is to pave the way for a semantic description of the types of content of elements in an XML document. The standard prescribes the existence of a naming convention for minting URI-based identifiers for all structural elements of a legal document. MetaLex explicitly encourages the use of RDFa attributes on its elements, and provides special metadata-elements for serialising additional RDF triples that cannot be expressed on structural elements themselves. MetaLex includes an ontology, which defines an event model for legislative modifications. The legislation.gov.uk portal has adopted the MetaLex event model for representing modifications.

Getting from BWB to CEN MetaLex

The MetaLex schema is designed to be independent of jurisdiction, which means that it should be possible to map each legacy XML element to a MetaLex element in an unambiguous fashion. Fortunately, we were able to define a straightforward 1:n mapping between BWB and MetaLex (see below) by a semi-automatic conversion of the BWB XML DTD.

The transformation of legacy XML to MetaLex and RDF is implemented in the MetaLex converter, an open source Python script available from GitHub. Conversion occurs in four stages:

- mapping legacy elements to MetaLex elements,

- minting identifiers for newly created elements,

- producing metadata for these elements, and

- serialising to appropriate formats.

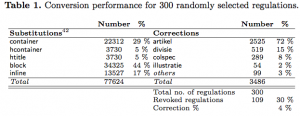

Step 1: Mapping

For the transformation of BWB XML files, the converter is sequentially fed with all BWB XML files and identifiers listed in the BWB ID index. Based on the mapping table, the converter traverses the DOM tree of the source document, and synchronously builds a DOM tree for the target document. In cases where the MetaLex schema doesn’t quite “fit,” the converter has to make additional repairs.

We evaluated the ability of MetaLex to map onto the BWB XML by running the converter on 300 randomly selected BWB identifiers. The artikel element accounts for 72% of all corrections, and corresponds to 68% of all htitle substitutions (5 % of total). This means that only a very small part of BWB XML does not directly fit onto the MetaLex schema. The main cause for incompatibility is the restriction in MetaLex that hcontainer elements are not allowed to contain block elements (and that’s perhaps something to consider for the MetaLex workshop).

Because of the limitations of the API, version information, citation titles, and other metadata are retrieved through a custom-built scraper of the information pages on the wetten.nl Website.

Step 2: Minting Identifiers

For every element in the document we create transparent URL-like URIs for the work, expression and manifestation levels, and two opaque URIs for the expression and item levels in the FRBR specification.

For transparent URIs, we use a naming scheme that is based on the URIs used at legislation.gov.uk, with slight adaptations to allow for the Dutch situation. In short, work level identifiers are based on the standard BWB identifier, followed by a hierarchical path to an element in the source, e.g., “chapter/1/article/1”. These URIs are extended to expression URIs by appending version and language information. Similarly, manifestation URIs are extensions of expression URIs that specify format information such as XML, RDF, etc. Juriconnect references in the source BWB XML are automatically translated to this naming scheme.

The opaque version URI is needed to distinguish different versions of a text. The current Webservice does not provide access to all versions of statutes and regulations (only to the latest), let alone at a level of granularity lower than entire statutes or regulations. We therefore need some way of constructing a version history by regularly checking for new versions, and comparing them to those we looked at before. By including in the opaque URI a unique SHA1 hash of the textual content of an XML element, and simultaneously maintaining a link between the opaque URI and the transparent identifier, different expressions of a work can be automatically distinguished through time. This is needed to work around issues with identifiers based on numbers: the insertion of a new element can change the position (and therefore the identifier) of other elements without a change in the content of the elements.

By this method, globally persistent URIs of every element in a legal text can be consistently generated for both current and future versions of the text. By simultaneously generating an opaque and a transparent expression level URI, identification of these text versions does not have to rely on numbering.

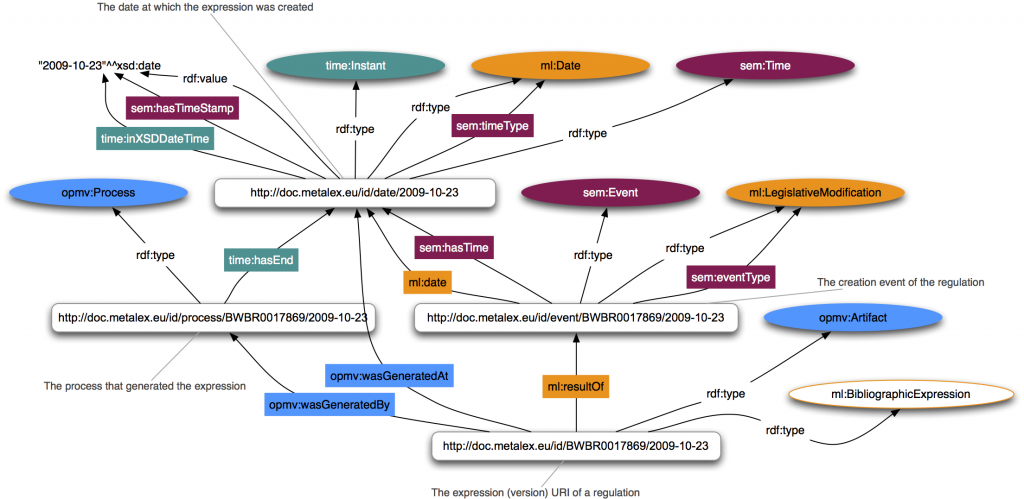

Step 3: Producing Metadata

The MetaLex converter produces three types of metadata. First, legacy metadata from attributes in the source XML is directly translated to RDF triples. Second, metadata describing the structural and identity relations between elements is created. This includes typing resources according to the MetaLex ontology, e.g., as ml:BibliographicExpression; creating ml:realizes relations between expressions and works; and creating owl:sameAs relations between opaque and transparent expression URIs. The official title, abbreviation, and publication date of statutes and regulations are represented using the dcterms:title, dcterms:alternative and dct:valid properties.

Events and Processes

Event information plays a central role in determining what version of a regulation was valid when. Making explicit which events and modifying processes contributed to an expression of a regulation provides for a flexible and extensible model. The MDS uses the MetaLex ontology for legislative modification events, the Simple Event Model (SEM) and the W3C Time Ontology for an abstract description of events and event types, and the Open Provenance Model Vocabulary (OPMV) for describing processes and provenance information. These vocabularies can be combined in a compatible fashion, allowing for maximal reuse of event and process descriptions by third parties that may not necessarily commit to the MetaLex ontology.

Step 4: Serialization

The MetaLex converter supports three formats for serialising a legal text to a manifestation: the MetaLex format itself, viewable in a browser by linking a CSS stylesheet; RDFa, Turtle and RDF/XML serializations of the RDF metadata; and a citation graph. The converter can automatically upload RDF to a triple store through either the Sesame API, or SPARQL updates. The citation graph is exported as a ‘”net” network file, for further analysis in social network software tools such as Pajek and Gephi. We are exploring ways to use these networks for determining the importance of articles (in degree) and the dependency of legislation on certain articles (betweenness centrality), and for analysing the correlation between legislation and case law.

Publication

The results of this procedure are published through the MetaLex Document Server (MDS). The server follows the Cool URIs specification, and implements HTTP-based redirects for work- and expression-level URIs to corresponding manifestations based on the HTTP accept header. Requests for an HTML mime-type are redirected to a Marbles HTML rendering of a Symmetric Concise Bounded Description (SCBD) of the RDF resource. Similarly, requests for RDF content return the SCBD itself; supported formats are RDF/XML and Turtle. A request for XML will return a snippet of MetaLex for the specified part of a statute or regulation.

The MDS provides two convenient methods for retrieving manifestations of a statute or regulation. Appending “/latest” to a work URI will redirect to the latest expression present in the triple store. Appending an arbitrary ISO date will return the last expression published before that date if no direct match is available. Lastly, the MDS offers a simple search interface for finding statutes and regulations based on the title and version date.

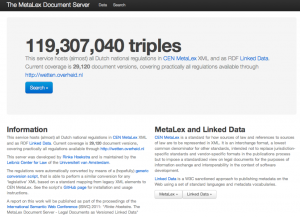

Results and Take Up

We have been running the converter on a daily basis, on all versions of statutes and regulations made available through the wetten.nl portal since May 2011. This has resulted in a current total of 29,120 document versions: 28 thousand versions in the first run, the rest accumulated through time. For these document versions, we now store 119 million triples of RDF metadata in a 4Store triple store. Compared to the size of legislation.gov.uk (1.9 billion triples, since the 1200s), this is a modest number, but at the current growth rate we will soon need to look for alternative (more professional) solutions. Check the http://doc.metalex.eu Website for the latest numbers.

We have been running the converter on a daily basis, on all versions of statutes and regulations made available through the wetten.nl portal since May 2011. This has resulted in a current total of 29,120 document versions: 28 thousand versions in the first run, the rest accumulated through time. For these document versions, we now store 119 million triples of RDF metadata in a 4Store triple store. Compared to the size of legislation.gov.uk (1.9 billion triples, since the 1200s), this is a modest number, but at the current growth rate we will soon need to look for alternative (more professional) solutions. Check the http://doc.metalex.eu Website for the latest numbers.

I am happy to say, also, that this work has not gone unnoticed. The IND was particularly enthused by the versioning mechanism, and is in the process of adopting the MDS approach as their internal content management system. Similarly, the ability to link concept descriptions to reliably versioned parts of legislation has been an eye opener for the Belastingdienst. We are also in touch with several people at ICTU, the organisation behind Wetten.nl, to help them improve their services.

Dr. Rinke Hoekstra is a postdoctoral researcher at the Leibniz Center for Law at the University of Amsterdam. He is the developer of the MetaLex Document Server, the principal author of the LKIF Core ontology of basic legal concepts, and one of the initial developers of the MetaLex XML format for legal sources.

Dr. Rinke Hoekstra is a postdoctoral researcher at the Leibniz Center for Law at the University of Amsterdam. He is the developer of the MetaLex Document Server, the principal author of the LKIF Core ontology of basic legal concepts, and one of the initial developers of the MetaLex XML format for legal sources.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor-in-Chief is Robert Richards, to whom queries should be directed. The statements above are not legal advice or legal representation. If you require legal advice, consult a lawyer. Find a lawyer in the Cornell LII Lawyer Directory.

The least-painful path at present is to visit

The least-painful path at present is to visit