This post explores ways in which information technology (IT) can enhance access to justice. What does it mean when we talk about “the access to justice crisis,” and how can information technology help to resolve it? The discussion that follows is based on my 2009 book, Technology for Justice: How Information Technology Can Support Judicial Reform, particularly Part 4, on the role of information and IT in access to justice.

The normative framework for access to justice

International conventions guarantee access to a court. Everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing by an independent tribunal in the determination of their civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge against him or her, according to The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (article 14) and regional conventions like the The European Convention on Human Rights (article 6). In practice, the normative framework for access to justice does not provide us with clearly defined concepts.

The major barriers to access to justice identified in the scholarly literature are:

- Distance, which can be a factor impeding access to courts. In many countries, courts are concentrated in the main urban centers or in the capital.

- Language barriers, which are present when justice seekers use a language that is different from the language of the courts.

- Physical challenges, like impaired sight and hearing and motor and cognitive impairments; these as a barrier to access are an emerging topic in the debate on technology support in courts.

These first three factors are all relatively straightforward and do not strike at the heart of the legal process.

- Cost, for instance lawyers’ fees, court fees and other components of the price of access to justice, in many forms, has been identified as a factor affecting access to courts. However, cost is extremely hard to research and subject to a lot of ramifications. Because of this complexity, cost will not be discussed directly in this post.

- Lack of information and knowledge, lack of familiarity with the court process, the complexity of legal and administrative systems, and lack of access to legal information are commonly identified factors (Cotterrell, The Sociology of Law p. 251; Hammergren, Envisioning Reform: Improving Judicial Performance in Latin America, p. 136). They are related because they all refer to the availability of information. They are the starting point for our discussion.

Potentially, information on the Internet can provide some form of solution for these problems, in two ways. First, access to information can support fairer administration of justice by equipping people to respond appropriately when confronted with problems with a potentially legal solution. Access to information can compensate, to some extent, for the disadvantage one-shotters experience in litigation, thereby increasing their chance of obtaining a fair decision. Second, the Internet provides a channel for legal information services, although experience with such online service provision is limited in most judiciaries. The discussion here will therefore focus on access to legal information and knowledge. Lack of information and knowledge as a barrier to access to justice is the focus for discussion in the first few paragraphs. The first step is to identify the barriers.

Knowledge and information barriers to access to justice

What are the information barriers individuals experience when they encounter problems with a potentially legal solution? We need empirical evidence to find an answer to this question, and fortunately some excellent research has been done, which may help us. In the U.K., Hazel Genn led a team that researched what people do and think about going to law. Their 1999 report is called Paths to Justice. A similar exercise led by Ben van Velthoven and Marijke ter Voert in The Netherlands, called Geschilbeslechtingsdelta 2003 (Dispute Resolution Delta 2003), was published in 2004. Although there are some marked differences between them, both studies looked at how people deal with “justiciable problems”: problems that are experienced as serious and have a potentially legal solution. Analysis of empirical evidence of people and their justiciable problems in England and Wales and The Netherlands produced the following findings with regard to these barriers:

- Inaction in the face of a justiciable problem because of lack of information and knowledge occurs in a small percentage of cases.

- Unavailability of advice negatively affects dispute resolution outcomes. It lowers the resolution rate. Cases in which people attempted to find advice were resolved with a higher rate of success than those of the self-helpers.

- Respecting the inability to find advice: If people go looking for advice, the barriers to finding it have more to do with their own competencies, such as confidence, emotional fortitude, and literacy skills, than with the availability of the advice. In the United Kingdom, about 20 percent of the population is so poor at reading and writing that they cannot cope with the demands of modern life, according to data from the National Literacy Trust. In The Netherlands, the percentage of similarly low literacy is estimated at about 10 percent, according to data from the Stichting Lezen en Schrijven, the Reading and Writing Foundation.

- Respecting incompetence in implementing the information received: Different competence levels will affect what can be done with information and advice. Competencies in implementing the information received include, for example, skills such as working out what the problem is, what result is wanted, and how to find help; simple case-recording skills; managing correspondence; confidence and assertiveness; and negotiating skills, according to research reported by Advicenow in 2005. Some people do not want to be empowered by having information available. They want assistance, or even someone to take over dealing with their problem. People with low levels of competence in terms of education, income, confidence, verbal skill, literacy skill, or emotional fortitude are likely to need some help in resolving justiciable problems.

- Ignorance about legal rights exists across most social groups. Genn notes that people generally are not educated about their legal rights (Genn p. 102).

- Respecting lack of confidence in the legal system and the courts and negative feelings about the justice system, Genn observes that people are unwilling voluntarily to become involved with the courts. People associate courts with criminal justice. People’s image of the courts is formed by media stories about high profile criminal cases (Genn p. 247). This issue is related to the public image of courts, as well as to the wider role of courts as setters of norms.

Information needs for resolving justiciable problems

After identifying knowledge and information barriers, the next step is to uncover needs for information and knowledge related to access to justice. Those needs are most strongly related to the type of problem people experience. The most frequently occurring justiciable problems are simple, easy-to-solve problems, mostly those concerning goods and services. People themselves resolve such problems, occasionally with advice from specialist organizations like the consumers’ unions (e.g., in the U.S., the National Consumers League). For more important, more complex problems, people tend to seek expert help more frequently. The most difficult to resolve are problems involving a longer-term relationship, such as labor or family problems. Any of the problems discussed in this section may lead to a court procedure. However, the problems that are the toughest to resolve are also the ones that most frequently come to court.

The first need people experience is for information on how to solve their problem. In The Netherlands, the primary sources for this type of information are specialized organizations, with legal advice providers in second place. In England and Wales, solicitors are the first port of call, followed by the Citizens’ Advice Bureaux. In both countries, the police are a significant source of information on justiciable problems. This is especially remarkable because the problems researched were not criminal justice issues.

If people require legal information, they primarily need straightforward information about rules and regulations. Next, they look for information about ways to settle and handle disputes once they arise. Information about court procedures is a separate category that becomes relevant only in the event people need to go to court.

Respecting taking their case to court: People need information on how to resolve problems, on rights and duties, and on taking a case to court. The justiciable problems that normally come to court tend to be difficult for people themselves to resolve. These problems are also experienced as serious. Many of them involve long-term relationships: family, employment, neighbors. Therefore, people will tend to go looking for advice. Some of them may need assistance. Most people seek and receive some kind of advice before they come to court.

In summary, information needs in this context are mostly problem-specific. Most problems are resolved by people themselves, sometimes with the help of information, or help in the form of advice or assistance. The help is provided by many different organizations, but mostly by specialized organizations or providers of legal aid and alternative dispute resolution (ADR).

Different dispute resolution cultures

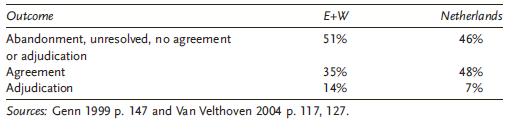

There are, besides these general trends, interesting differences between England and Wales and The Netherlands. The results with regard to dispute outcome, for instance, show the following:

The Netherlands has fewer unresolved disputes, more disputes resolved by agreement, and the rate of resolution by adjudication is half that of England and Wales. It looks as if there is more capacity for resolving justiciable problems in Dutch society than there is in society in England and Wales. Apart from the legacy of the justice system where there is a propensity to settle differences that Voltaire described in one of his letters, many factors may be at work in The Netherlands to produce a higher level of problem-solving capacity. One probable factor is the level of education and the related competence levels for dealing with problems and the legal framework. The functional illiteracy rate is only half that in the United Kingdom. Another factor may be a propensity to settle differences by reducing the complexity of problems through policies and routines.

Diversion or access, empowerment or court improvement?

The debate respecting whether diversion or court improvement should come first as an objective of legal policy, has been going on for some time. These are the options under discussion:

- Preventing problems and disputes from arising;

- Equipping as many members of the public as possible to solve problems when they do arise without needing recourse to legal action;

- Diverting cases away from the courts into private dispute resolution forums; and

- Enhancing access to legal forums for the resolution of disputes.

Genn argues that it is not an answer to say that diversion and access should be the twin objectives of policy, because they logically conflict. I would like to contribute some observations that could provide a way out of this apparent dilemma.

First, user statistics from the introduction of the online claim service Money Claim Online and the case study in Chapter 2.3 of my book suggest that changes in procedure facilitating access do not in themselves lead to higher caseloads. Changes observed in the caseloads are attributable to market forces in both instances.

The other observation is that Paths to Justice and the Dispute Resolution Delta clearly found that self-help is experienced as more satisfying and less stressful than legal proceedings. Moreover, resolutions are to a large degree problem specific. A way out of the dilemma could be that specialist organizations that make it their business to provide specific information, advice, and assistance, should enhance their role. There is an empirical basis for this way out in the research reported in Paths to Justice and the Dispute Resolution Delta. Although goods and services problems are largely resolved through self-help, out-of-court settlement, or ADR, nonetheless a fair number of them still come to court. Devising ways to assist individuals in informal problem solving and diverting them to other dispute resolution mechanisms can keep still more of these problems out of court. Even in matters for which a court decision is compulsory, like divorce, mediation mechanisms can sort out differences before the case is filed. Clearly, information on the Internet will provide an entry point for all of these dispute resolution services. Online information can thus help to keep as many problems out of court as possible. All this should not keep us from making going to court when necessary less stressful. Information can help reduce people’s stress, even as it improves their chances of achieving justice. The Internet can be a vehicle for this kind of information service, too.

Taking up this point, the next section focuses on courts and how information technology, particularly the Internet, can support them in their role of information providers to improve access to justice. Two strains concerning the role of information in access to justice run through this theme: information to keep disputes out of court, and information on taking disputes to court.

Information to keep disputes out of court

An almost implicit understanding in the research literature is that parties with information on the “rules of thumb” of how courts deal with types of disputes will settle their differences more easily and keep them out of court. Such information supports settlement in the shadow of the law. Most of this type of settlement will be done with the support of legal or specialist organizations. In the pre-litigation stage, information about the approaches judges and courts generally take to specific types of problems can help the informal resolution of those problems. This will require that information about the way courts deal with those types of problems becomes available. Some of the ways in which courts deal with specific issues are laid down in policies. Moreover, judicial decision making is sometimes assisted by decision support systems reflecting policies. In order to help out-of-court settlement, policies and decision support systems need to be available publicly.

Information on taking disputes to court

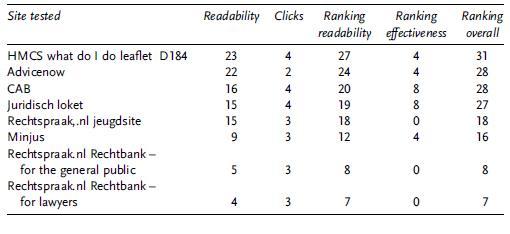

If a dispute needs to come to court, information can reduce the disadvantage one-shotters have in dealing with the court and with legal issues. This disadvantage of the one-shotters — those who come to court only occasionally — over against the repeat players who use courts as a matter of business, was enunciated by Marc Galanter in his classic 1974 article, Why the Haves Come Out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal Change. Access to information for individual, self-represented litigants increases their chances of obtaining just and fair decisions. Litigants need information on how to take their case to court. This information needs to be legally correct, as well as effective. By “effective,” I mean that the general public can understand the information, and that someone after reading it will (1) know what to do next, and (2) be confident that this action will yield the desired result. In a case study, I have rated several court-related Web sites in the U.K. and in The Netherlands on those points, and found most of them wanting. My test was done in 2008, and most of the sites have since changed or been replaced. And although the U.K. Court Service leaflet D 184 on how to get a divorce got the best score, my favorite Web site is Advicenow.

Such an information service requires a proactive, demand-oriented attitude from courts and judiciaries. Multi-channel information services, such as a letter from the court with reference to information on the court’s or judiciary’s Web site, can meet people’s information needs.

Beyond information push

Other forms of IT, increasingly interactive, can provide access to court. [Editor’s note: Document assembly systems for self-represented litigants are a notable example.] Not all of them require full-scale implementation of electronic case management and electronic files. In order to be effective for everyone, the information services discussed will require human help backup. There are also technologies to provide this, but they may still not be sufficient for everyone. The information services discussed here, in order to be effective, will need to be provided by a central agency for the entire legal system. A final finding is the importance of public trust in the courts in order for individuals to achieve access to justice. Judiciaries can actively contribute to improved access to justice in this field by ensuring that correct information about their processes is furnished to the public.

In summary, access to justice can be effectively improved with IT services. Such services can help to ameliorate the access-to-justice crisis by keeping disputes out of court. The information services identified here should serve the purpose of getting justice done. They should not keep people from getting the justice they deserve by preventing them from taking a justified concern to court. If people need to go to court, information services can help them deal with the courts more effectively.

[Editor’s Note: A very useful list of resources about applying technology to access to justice appears at the technola blog.]

Dory Reiling, mag. iur. Ph.D., is a judge in the first instance court in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. She was the first information manager for The Netherlands’ Judiciary, and a senior judicial reform expert at The World Bank. She is currently on the editorial board of The Hague Journal on the Rule of Law and on the Board of Governors of The Netherlands’ Judiciary’s Web site Rechtspraak.nl. She has a Weblog in Dutch, and an occasional Weblog in English, and can be followed on Twitter at @doryontour.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor in chief is Robert Richards.

Two years ago my collaborators and I introduced a new resource for understanding constitutions. We call it Constitute. It’s a web application that allows users to extract excerpts of constitutional text, by topic, for nearly every constitution in the world currently in force. One of our goals is to shed some of the drudgery associated with reading legal text. Unlike credit card contracts, Constitutions were meant for reading (and by non-lawyers). We have updated the site again, just in time for summer (See below). Curl up in your favorite retreat with Constitute this summer and tell us what you think.

Two years ago my collaborators and I introduced a new resource for understanding constitutions. We call it Constitute. It’s a web application that allows users to extract excerpts of constitutional text, by topic, for nearly every constitution in the world currently in force. One of our goals is to shed some of the drudgery associated with reading legal text. Unlike credit card contracts, Constitutions were meant for reading (and by non-lawyers). We have updated the site again, just in time for summer (See below). Curl up in your favorite retreat with Constitute this summer and tell us what you think. (with some evidence) that readers strongly prefer to read constitutions in their native language. Thus, with a nod to the constitutional activity borne of the Arab Spring, we have introduced a fully functioning Arabic version of the site, which includes a subset of Constitute’s texts. Thanks here to our partners at International IDEA, who provided valuable intellectual and material resources.

(with some evidence) that readers strongly prefer to read constitutions in their native language. Thus, with a nod to the constitutional activity borne of the Arab Spring, we have introduced a fully functioning Arabic version of the site, which includes a subset of Constitute’s texts. Thanks here to our partners at International IDEA, who provided valuable intellectual and material resources.

As a comparative law academic, I have had an interest in legal translation for some time. I’m not alone. In our

As a comparative law academic, I have had an interest in legal translation for some time. I’m not alone. In our  Frank Bennett

Frank Bennett