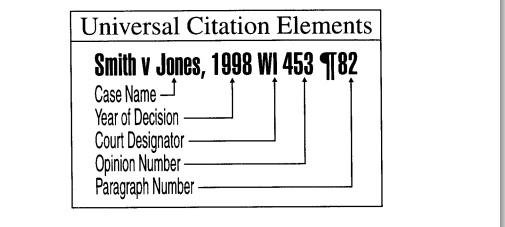

Source: AALL Universal Citation Guide (First Edition).

In his recent post, Fastcase CEO Ed Walters called on American states to tear down the copyright paywall for statutes. States that assert copyright over public laws limit their citizens’ access to such laws and impede a free and educated society. Convincing states (and publishers) to surrender these claims, however, is going to take some time.

A parallel problem involves The Bluebook and the courts that endorse it as a citation authority. By requiring parties to cite to an official published version of a statutory code, the courts are effectively restricting participants in the legal research market. Nowhere is this more evident than in those states where the government has delegated the publishing of the official code to a private publisher, as is the situation in more than half of the states. Thus, even if the state itself or another company, such as Justia, publishes the law online for free, a brief cannot cite to these versions of the code.

To remedy this problem, we (and others) propose applying a system of vendor neutral (universal) citation to all primary legal source material, starting with the state codes. Assigning a universal, uniform identifier for state codes will make them easier to find, use, and cite. While we do not expect an immediate endorsement from The Bluebook, we hope that once these citations find their way into the stream of information, people will use them and states will take notice. We think it’s time to bring disruptive technology to bear on the legal information industry.

About Universal Citation

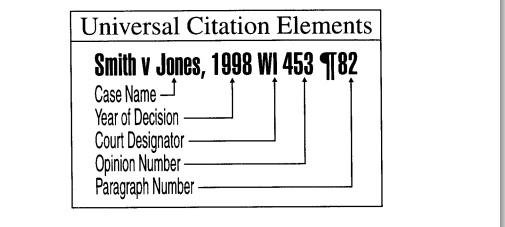

“Universal citation” refers to a non-proprietary legal citation that is applied the instant a document is created. “Universal citation” is also called a “vendor-neutral,” “media-neutral,” or “public domain” citation. Universal citation has been adopted by sixteen U.S. states in order to cite caselaw, but universal citation has not yet been applied to statutes by any state. A review of universal citation processes for caselaw is helpful in understanding how we may apply universal citation to statutes.

Briefly, a case follows this process before appearing as an official reported decision:

When issuing a written decision, a court first releases a draft called a slip opinion, which is often posted on the court’s Website. Private publishers then republish the slip opinion in various legal databases. A party can cite the slip opinion using a variety of citation formats, depending on the database.

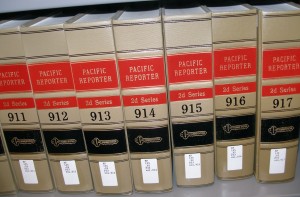

Afterwards, the court transmits the slip opinion to the jurisdiction’s Reporter of Decisions, who may be a member of the judicial system or a private company. The Reporter edits the opinions, and then collects and reprints them in a bound volume with a citation. To cite a particular page within a case, which is also referred to as pinpoint citation, a party cites the case name, the publication, the volume, and the specific page number that contains the cited content.

Before the advent of electronic publishing, these books were the primary source for legal research. And, while publishers still print cases in book format, the majority of users read the cases in digital form. However, opinions in online database lack physical pages. To address this, online publishers insert page numbers into the digital version of an opinion to correspond to page breaks in the print version. Thus, the pinpoint citation (or star pagination) for an opinion, whether in print or online, is the same.

Under most court rules, and Bluebook guidance, once the official opinion is published, the Reporter citation must be used (see Bluebook Rule 10.3.1).

The decisions are published by a private company, usually Thomson West, and anyone wanting to read them must license the material from the company. Thus, if you want to cite to judicial law, you must pay to access the Reporter’s opinions. (Public law libraries offer books and database access, but readers must visit the physical library to use their resources. Google Scholar also provides free access to official cases online, but they must pay to obtain and license the opinions. In other words, Google, not the end user, is paying for the access.)

Universal citation bypasses the private publisher, and allows courts to create official opinions immediately. Under this system, judges assign a citation to the case when they release it. They insert paragraph numbers into the body of the opinion to allow pinpoint citation. This way, the case is instantly citeable. There is no intermediary lag time between slip and official opinion where different publishers cite the case differently, and there is no need to license proprietary databases in order to read and cite the work. In the jurisdictions that have adopted this system, the court’s opinion is the final, official version. Private publishers may republish and add their own parallel citations, but in most jurisdictions the court does not require citation to private publishers’ versions. (However, Louisiana and Montana require parallel citation to the regional reporter.)

The American Association of Law Libraries (AALL) developed the initial standards for vendor neutral citation formats. AALL published the Universal Citation Guide in 1999, and released an updated edition in 2004. The Bluebook adopted a similar scheme in Rule 10.3.3 – Public Domain Format. Under this format, a universal citation should include the following:

- Year of decision

- State’s 2-letter postal code

- Court name abbreviation

- Sequential number of the decision

- “U” for unpublished cases

- Pinpoint citation should reference the paragraph number, instead of the page number

The majority of states employing universal citation follow the AALL/Bluebook standard, but a few have adopted their own styles. (Illinois, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, and Ohio employ universal citation but use a different format than the AALL/Bluebook recommendation.)

Most states that use universal citation adopted it in the 1990s. Cornell Law Professor Peter Martin details these events in his article Neutral Citation, Court Websites, and Access to Authoritative Caselaw. Professor Ian Gallacher of Albany Law School has also written about the history of this movement in Cite Unseen: How Neutral Citation and Americas Law Schools Can Cure Our Strange Devotion to Bibliographical Orthodoxy and the Constriction of Open and Equal Access to the Law. To date, 16 states assign universal citations to their highest court opinions. (To date, Arkansas, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Wyoming have adopted universal citation for caselaw.) Illinois is the most recent state to adopt the measure (in June 2011), and the concept has been gaining traction in the legal blogosphere. John Joergensen at Rutgers-Camden School of Law started a cooperative effort called UniversalCitation.org this summer.

Universal Citation and State Codes

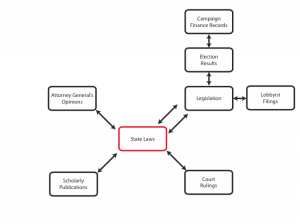

Applying universal citation to state statutes can provide the same benefits as to caselaw, making statutes easier to find and cite, and improving access. While all states publish some form of their laws online for the public, as Ed has noted, these versions of state laws are often burdened by copyright and licensing restrictions. With these restrictions in place, users are not free to reuse, remix, or republish law, resulting in stifled innovation and external costs associated with using poorly designed Websites that take longer to search.

Though the AALL provides guidance on universal citation for statutes, no state has adopted it. The Bluebook does not specifically reference universal forms of citations for statutes and generally requires citation to official code compilations. There are exceptions for the digital version of the official code, parallel citations to other sources, and the use of unofficial sources where they are the only available source. (Bluebook Rule 12 provides for citation to statutes, generally. The Bluebook addresses Internet sources in Rule 18.)

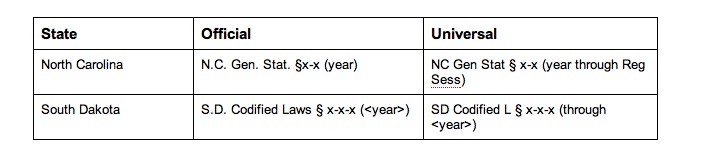

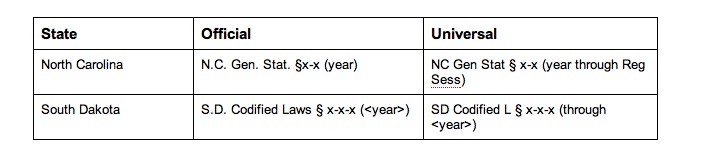

The AALL’s Universal Citation Guide provides a schema for citing statutes in a neutral format. Rules 305-307 lay out standardized code designations, numbering, and dating rules, and each state has a full description in the Appendices. Basically, the format uses the state postal code, abbreviations for the name of the statutes (Consolidated, Revised, etc.), and a date.

As a result, the universal citations look similar to the official citations.

The AALL universal citation uses a name abbreviation for the state name and the name of the statute compilation. AALL’s format does not use periods in the abbreviations. It also uses a different convention for the year. The Guide’s recommendation is to date the code by a “legislative event,” to make the date more precise. Using “current through” dating provides a timestamp for the version of the code being used. This approach is less ambiguous than listing simply the year.

The AALL universal citation uses a name abbreviation for the state name and the name of the statute compilation. AALL’s format does not use periods in the abbreviations. It also uses a different convention for the year. The Guide’s recommendation is to date the code by a “legislative event,” to make the date more precise. Using “current through” dating provides a timestamp for the version of the code being used. This approach is less ambiguous than listing simply the year.

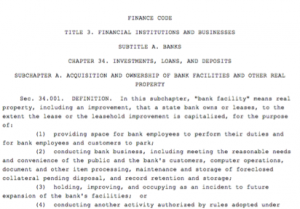

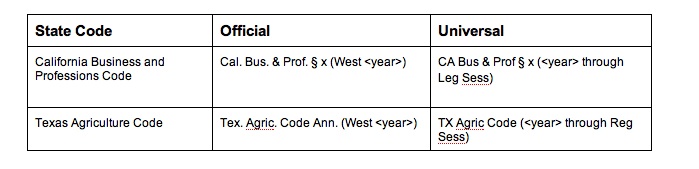

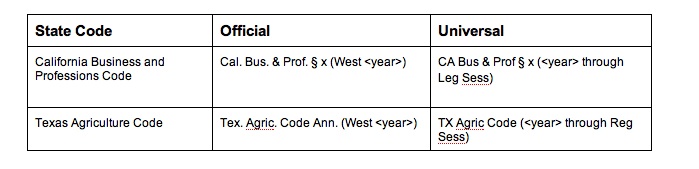

States like California and Texas have very large, segmented code systems with more complicated official citation schemes. The AALL mirrors these with the universal version, giving each subject matter code an abbreviation similar to the one used by The Bluebook.

Universal citation does not designate whether the code version is annotated, and of course it does not mention the publisher of the source.

Experimenting with Universal Citation

Justia is now applying the AALL’s universal citation to the code compilations on our site. We add this citation to the most granular instance of the code citation, along with a statement identifying and explaining it. So far, we’ve added citations to the state codes of Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, and South Dakota.

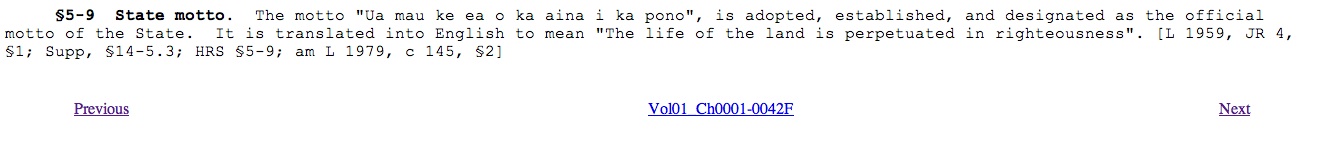

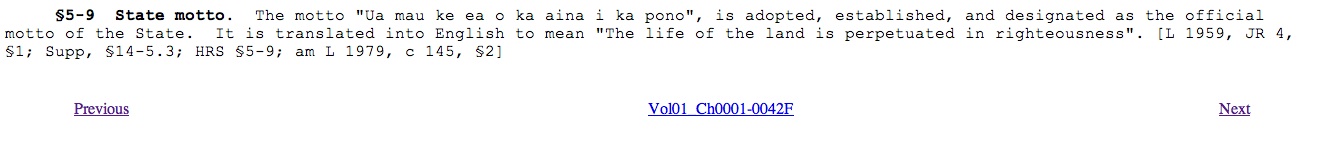

We started with Hawaii. The official citation and the universal citation are fairly similar:

Official: Haw. Rev. Stat. § 5-9 (2010)

Universal: HI Rev Stat § x-x (2010 Reg Sess)

This is how the code looks on the Hawaii Legislature’s site:

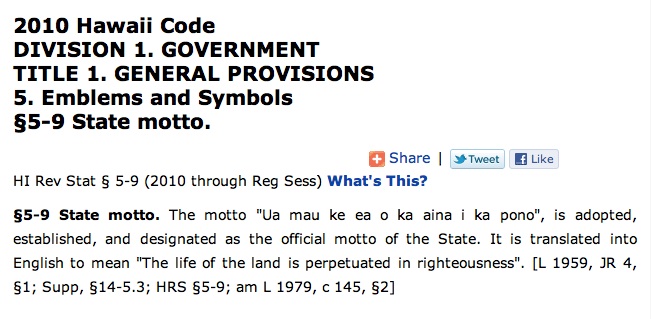

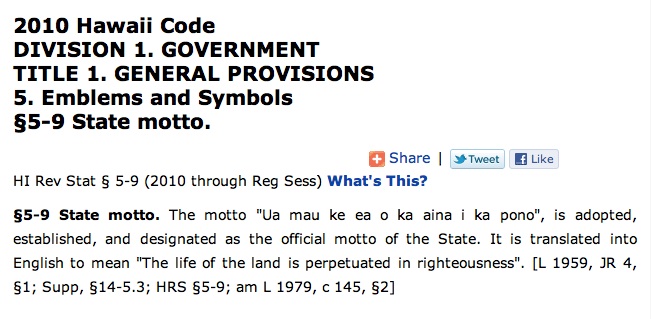

This is how the code section looks on Justia. We added the citation right above the text of the statute.

On our site, the full citation is visible, so readers can quickly identify and cite to it. The “What’s This?” link next to the citation explains the universal citation.

We used the Legislature’s site to determine the date.

We also added the universal citation to the title tags. This allows search engine users to see the universal citation in their search results. It makes the search results more readable, because the text of the statute name appears next to the citation. For example, compare a search for “Haw Rev Stat 5-9”

with “HI Rev Stat 5-9”:

With the search results for the universal citation (properly tagged), more information about that citation is presented. This helps the user quickly identify and digest the best search results.

We hope to accomplish three objectives by attaching universal citations to our codes. First, we want to give people an easy way to cite the code without having to look at proprietary publications. Not all citation goes into legal briefs or other documents that require formal citation to “official” sources listed by The Bluebook. The AALL universal citation scheme is easy to read and understand, and uses familiar abbreviations (like postal codes). Providing a citation right on the page of the code section will help people talk about, use, and cite to code sections without having to access “official” sources behind a paywall.

Second, we hope to demonstrate that universal citation can be applied in an easy and straightforward manner. The AALL has already developed a rigorous standard for universal citation; we are happy to use it and not reinvent the wheel. Legal folks here at Justia researched the AALL citation and the proper year/date information, and programmers applied the citation to the corpus. Anyone can do this, including the states.

Third, we want to encourage the adoption and widespread use of vendor-neutral citation schemes. There’s been a lot of talk about vendor-neutral citation for caselaw, and we are excited by efforts like UniversalCitation.org. Applying these principles to state codes will help get universal citation into the stream of legal information online. Just seeing the citation and the “What’s This?” page next to it will introduce readers to the concept. The more people use universal citations for state statutes, the more states will be forced to examine their reliance on third party publishers as the “official” source.

Next Steps

We plan to apply the universal citation to all of the codes in our corpus, but we have encountered some obstacles to achieving this for all 50 states. First, some of the codes are quite large and difficult to parse. Ari Hershowitz has documented his efforts to convert the California code into usable HTML. States like California, Texas, and New York will be more labor intensive. Second, the currency, or timestamp, is not always readily apparent on the state code site. With Idaho, I had to make a call to the Legislative Office to find out exactly when they last updated the code.

Source: AALL Universal Citation Guide (First Edition).

The third, and perhaps most troubling, issue is the “unofficial” status of the online state code repositories. With the exception of a few states (see Colorado), the codes hosted on the states’ own Websites are papered over with disclaimers about their authenticity. While I understand the preference for “official” sources when citing a code, there seems to be no good reason why the official statutes of any state are not available online, for free, for everyone. These are the laws we must obey and to which we are held accountable. Does the public really deserve something less than official version? The states are passing the buck by disclaiming all responsibility for publishing their own laws, and relying on third-party publishers, which charge taxpayers to view the laws that the taxpayers paid for. I hope that as we apply a universal citation to our state statutes, the law will become more usable for the public. By taking disruptive action and applying these rules to our large corpus of data, we hope that more people will see the statutes and cite using universal principles, and that the states will take notice.

We have assigned a universal citation to the first few states as a proof of concept. We will also be sharing our efforts by supplying copies of the code with the universal citations included for bulk download at public.resource.org. As we move forward with the remaining 46 states, we would love your input. Comment here or contact me directly with your thoughts.

Peace and Onward.

[Editor’s Note: For other VoxPopuLII posts on universal citation and the status of content in legal repositories, see Ivan Mokanov’s post on the Canadian neutral citation standard, and John Joergensen’s post on authentication of digital legal repositories.]

Courtney Minick is an attorney and product manager at Justia, where she works on free law and open access initiatives. She can be found pushing her agenda at the Justia Law, Technology, and Legal Marketing Blog and on Twitter: @caminick.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor-in-Chief is Robert Richards, to whom queries should be directed. The statements above are not legal advice or legal representation. If you require legal advice, consult a lawyer. Find a lawyer in the Cornell LII Lawyer Directory.

about the provenance of case opinions you will only learn half the story. Rose can tell you that after she and her judge finish an opinion it gets sent to a permanent court staffer. After that the story that Rose knows basically ends. The opinion at this stage is in its “slip” opinion state, and only some time later will Rose see the “official” version – which will have a citation number, copy edits, and perhaps other alterations. Yet, it is only this new “official” version that may be cited in court. For Mike Lissner, for Ravel, and for many others, the crux of the access challenge lies in steps beyond Rose’s domain, beyond the individual court’s in fact – when a slip becomes an official opinion.

about the provenance of case opinions you will only learn half the story. Rose can tell you that after she and her judge finish an opinion it gets sent to a permanent court staffer. After that the story that Rose knows basically ends. The opinion at this stage is in its “slip” opinion state, and only some time later will Rose see the “official” version – which will have a citation number, copy edits, and perhaps other alterations. Yet, it is only this new “official” version that may be cited in court. For Mike Lissner, for Ravel, and for many others, the crux of the access challenge lies in steps beyond Rose’s domain, beyond the individual court’s in fact – when a slip becomes an official opinion. primary effort in this regard is FDsys (and also see the 9th Circuit’s recent moves). But FDsys’s present course gives reason to worry that its goals have been too narrowly conceived to achieve serious benefit. This discourages the program’s natural supporters and endangers its chances of success.

primary effort in this regard is FDsys (and also see the 9th Circuit’s recent moves). But FDsys’s present course gives reason to worry that its goals have been too narrowly conceived to achieve serious benefit. This discourages the program’s natural supporters and endangers its chances of success. format is easy and comes at virtually no additional cost. It can be done in addition to publishing in PDF. Courts and the GPO already have electronic versions of cases and with a few mouse clicks could store them in a format that would inspire innovation rather than hamper it. The legal technology community stands ready to assist with advice and development work on all of these issues.

format is easy and comes at virtually no additional cost. It can be done in addition to publishing in PDF. Courts and the GPO already have electronic versions of cases and with a few mouse clicks could store them in a format that would inspire innovation rather than hamper it. The legal technology community stands ready to assist with advice and development work on all of these issues. Daniel Lewis and Nik Reed are graduates of Stanford Law School and the co-founders of Ravel Law, a legal search, analytics, and collaboration platform. In 2012, Ravel spun out of a Stanford University Law School, Computer Science Department, and Design School collaborative research effort focused on legal citation networks and information design. The Ravel team includes software engineers and data scientists from Stanford, MIT, and Georgia Tech. You can follow them on Twitter @ravellaw

Daniel Lewis and Nik Reed are graduates of Stanford Law School and the co-founders of Ravel Law, a legal search, analytics, and collaboration platform. In 2012, Ravel spun out of a Stanford University Law School, Computer Science Department, and Design School collaborative research effort focused on legal citation networks and information design. The Ravel team includes software engineers and data scientists from Stanford, MIT, and Georgia Tech. You can follow them on Twitter @ravellaw