1. The Death and Life of Great Legal Data Standards

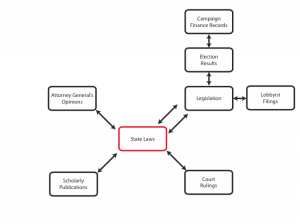

Thanks to the many efforts of the open government movement in the past decade, the benefits of machine-readable legal data — legal data which can be processed and easily interpreted by computers — are now widely understood. In the world of government statutes and reports, machine-readability would significantly enhance public transparency, help to increase efficiencies in providing services to the public, and make it possible for innovators to develop third-party services that enhance civic life.

Thanks to the many efforts of the open government movement in the past decade, the benefits of machine-readable legal data — legal data which can be processed and easily interpreted by computers — are now widely understood. In the world of government statutes and reports, machine-readability would significantly enhance public transparency, help to increase efficiencies in providing services to the public, and make it possible for innovators to develop third-party services that enhance civic life.

In the universe of private legal data — that of contracts, briefs, and memos — machine-readability would open up vast potential efficiencies within the law firm context, allow the development of novel approaches to processing the law, and would help to drive down the costs of providing legal services.

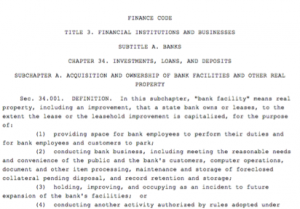

However, while the benefits are understood, by and large the vision of rendering the vast majority of legal documents into a machine-readable standard has not been realized. While projects do exist to acquire and release statutory language in a machine-readable format (and the government has backed similar initiatives), the vast body of contractual language and other private legal documents remains trapped in a closed universe of hard copies, PDFs, unstructured plaintext and Microsoft Word files.

Though this is a relatively technical point, it has broad policy implications for society at large. Perhaps the biggest upshot is that machine-readability promises to vastly improve access to the legal system, not only for those seeking legal services, but also for those seeking to provide legal services, as well.

It is not for lack of a standard specification that the status quo exists. Indeed, projects like LegalXML have developed specifications that describe a machine-readable markup for a vast range of different types of legal documents. As of writing, the project includes technical committees working on legislative documents, contracts, court filings, citations, and more.

However, by and large these efforts to develop machine-readable specifications for legal data have only solved part of the problem. Creating the standard is one thing, but actually driving adoption of a legal data standard is another (often more difficult) matter. There are a number of reasons why existing standards have failed to gain traction among the creators of legal data.

For one, the oft-cited aversion of lawyers to technology remains a relevant factor. Particularly in the case of the standardization of legal data, where the projected benefits exist in the future and the magnitude of benefit speculative at the present moment, persuading lawyers and legislatures to adopt a new standard remains a challenge, at best.

Secondly, the financial incentives of some actors may actually be opposed towards rendering the universe of legal documents into a machine-readable standard. A universe of largely machine-readable legal documents would also be one in which it may be possible for third-parties to develop systems that automate and significantly streamline legal services. In the context of the ever-present billable hour, parties may resist the introduction of technological shifts that enable these efficiencies to emerge.

Third, the costs of converting existing legal data into a machine-readable standard may also pose a significant barrier to adoption. Marking up unstructured legal text can be highly costly depending on the intended machine usage of the document and the type of document in question. Persuading a legislature, firm, or other organization with a large existing repository of legal documents to take on large one-time costs to render the documents into a common standard also discourages adoption.

These three reinforcing forces erect a significant cultural and economic barrier against the integration of machine-readable standards into the production of legal text. To the extent that one believes in the benefits from standardization for the legal industry and society at large, the issue is — in fact — not how to define a standard, but how to establish one.

2. Rough Consensus, Running Standards

So, how might one go about promulgating a standard? Particularly in a world in which lawyers, the very actors that produce the bulk of legal data, are resistant to change, mere attempts to mobilize the legal community to action are destined to fail in bringing about the fundamental shift necessary to render most if not all legal documents in a common machine-readable format.

In such a context, implementing a standard in a way that removes humans from the loop entirely may, in fact, be more effective. To do so, one might design code that was capable of automatically rendering legal text into a machine-readable format. This code could then be implemented by applications of all kinds, which would output legal documents in a standard format by default. This would include the word processors used by lawyers, but also integration with platforms like LegalZoom or RocketLawyer that routinely generate large quantities of legal data. Such a solution would eliminate the need for lawyer involvement from the process of implementing a standard entirely: any text created would be automatically parsed and outputted in a machine readable format. Scripts might also be written to identify legal documents online and process them into a common format. As the body of documents rendered in a given format grew, it would be possible for others to write software leveraging the increased penetration of the standard.

There are — obviously — technical limitations in realizing this vision of a generalized legal data parser. For one, designing a truly comprehensive parser is a massively difficult computer science challenge. Legal documents come in a vast diversity of flavors, and no common textual conventions allow for the perfect accurate parsing of the semantic content of any given legal text. Quite simply, any parser will be an imperfect (perhaps highly imperfect) approximation of full machine-readability.

Despite the lack of a perfect solution, an open question exists as to whether or not an extremely rough parsing system, implemented at sufficient scale, would be enough to kickstart the creation of a true common standard for legal text. A popular solution, however imperfect, would encourage others to implement nuances to the code. It would also encourage the design of applications for documents rendered in the standard. Beginning from the roughest of parsers, a functional standard might become the platform for a much bigger change in the nature of legal documents. The key is to achieve the “minimal viable standard” that will begin the snowball rolling down the hill: the point at which the parser is rendering sufficient legal documents in a common format that additional value can be created by improving the parser and applying it to an ever broader scope of legal data.

But, what is the critical mass of documents one might need? How effective would the parser need to be in order to achieve the initial wave of adoption? Discovering this, and learning whether or not such a strategy would be effective, is at the heart of the Restatement project.

3. Introducing Project Restatement

Supported by a grant from the Knight Foundation Prototype Fund, Restatement is a simple, rough-and-ready system which automatically parses legal text into a basic machine-readable JSON format. It has also been released under the permissive terms of the MIT License, to encourage active experimentation and implementation.

The concept is to develop an easily-extensible system which parses through legal text and looks for some common features to render into a standard format. Our general design principle in developing the parser was to begin with only the most simple features common to nearly all legal documents. This includes the parsing of headers, section information, and “blanks” for inputs in legal documents like contracts. As a demonstration of the potential application of Restatement, we’re also designing a viewer that takes documents rendered in the Restatement format and displays them in a simple, beautiful, web-readable version.

Underneath the hood, Restatement is all built upon web technology. This was a deliberate choice, as Restatement aims to provide a usable alternative to document formats like PDF and Microsoft Word. We want to make it easy for developers to write software that displays and modifies legal documents in the browser.

In particular, Restatement is built entirely in JavaScript. The past few years have been exciting for the JavaScript community. We’ve seen an incredible flourishing of not only new projects built on JavaScript, but also new tools for building cool new things with JavaScript. It seemed clear to us that it’s the platform to build on right now, so we wrote the Restatement parser and viewer in JavaScript, and made the Restatement format itself a type of JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) document.

For those who are more technically inclined, we also knew that Restatement needed a parser formalism, that is, a precise way to define how plain text can get transformed into Restatement format. We became interested in recent advance in parsing technology, called PEG (Parsing Expression Grammar).

PEG parsers are different from other types of parsers; they’re unambiguous. That means that plain text passing through a PEG parser has only one possible valid parsed output. We became excited about using the deterministic property of PEG to mix parsing rules and code, and that’s when we found peg.js.

With peg.js, we can generate a grammar that executes JavaScript code as it parses your document. This hybrid approach is super powerful. It allows us to have all of the advantages of using a parser formalism (like speed and unambiguity) while also allowing us to run custom JavaScript code on each bit of your document as it parses. That way we can use an external library, like the Sunlight Foundation’s fantastic citation, from inside the parser.

Our next step is to prototype an “interactive parser,” a tool for attorneys to define the structure of their documents and see how they parse. Behind the scenes, this interactive parser will generate peg.js programs and run them against plaintext without the user even being aware of how the underlying parser is written. We hope that this approach will provide users with the right balance of power and usability.

4. Moving Forwards

Restatement is going fully operational in June 2014. After launch, the two remaining challenges are to (a) continuing expanding the range of legal document features the parser will be able to successfully process, and (b) begin widely processing legal documents into the Restatement format.

For the first, we’re encouraging a community of legal technologists to play around with Restatement, break it as much as possible, and give us feedback. Running Restatement against a host of different legal documents and seeing where it fails will expose the areas that are necessary to bolster the parser to expand its potential applicability as far as possible.

For the second, Restatement will be rendering popular legal documents in the format, and partnering with platforms to integrate Restatement into the legal content they produce. We’re excited to say on launch Restatement will be releasing the standard form documents used by the startup accelerator Y Combinator, and Series Seed, an open source project around seed financing created by Fenwick & West.

It is worth adding that the Restatement team is always looking for collaborators. If what’s been described here interests you, please drop us a line! I’m available at tim@robotandhwang.org, and on Twitter @RobotandHwang.

Jason Boehmig is a corporate attorney at Fenwick & West LLP, a law firm specializing in technology and life science matters. His practice focuses on startups and venture capital, with a particular emphasis on early stage issues. He is an active maintainer of the Series Seed Documents, an open source set of equity financing documents. Prior to attending law school, Jason worked for Lehman Brothers, Inc. as an analyst and then as an associate in their Fixed Income Division.

Jason Boehmig is a corporate attorney at Fenwick & West LLP, a law firm specializing in technology and life science matters. His practice focuses on startups and venture capital, with a particular emphasis on early stage issues. He is an active maintainer of the Series Seed Documents, an open source set of equity financing documents. Prior to attending law school, Jason worked for Lehman Brothers, Inc. as an analyst and then as an associate in their Fixed Income Division.

Tim Hwang currently serves as the managing human partner at the offices of Robot, Robot & Hwang LLP. He is curator and chair for the Stanford Center on Legal Informatics FutureLaw 2014 Conference, and organized the New and Emerging Legal Infrastructures Conference (NELIC) at Berkeley Law in 2010. He is also the founder of the Awesome Foundation for the Arts and Sciences, a distributed, worldwide philanthropic organization founded to provide lightweight grants to projects that forward the interest of awesomeness in the universe. Previously, he has worked at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University, Creative Commons, Mozilla Foundation, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation. For his work, he has appeared in the New York Times, Forbes, Wired Magazine, the Washington Post, the Atlantic Monthly, Fast Company, and the Wall Street Journal, among others. He enjoys ice cream.

Tim Hwang currently serves as the managing human partner at the offices of Robot, Robot & Hwang LLP. He is curator and chair for the Stanford Center on Legal Informatics FutureLaw 2014 Conference, and organized the New and Emerging Legal Infrastructures Conference (NELIC) at Berkeley Law in 2010. He is also the founder of the Awesome Foundation for the Arts and Sciences, a distributed, worldwide philanthropic organization founded to provide lightweight grants to projects that forward the interest of awesomeness in the universe. Previously, he has worked at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University, Creative Commons, Mozilla Foundation, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation. For his work, he has appeared in the New York Times, Forbes, Wired Magazine, the Washington Post, the Atlantic Monthly, Fast Company, and the Wall Street Journal, among others. He enjoys ice cream.

Paul Sawaya is a software developer currently working on Restatement, an open source toolkit to parse, manipulate, and publish legal documents on the web. He previously worked on identity at Mozilla, and studied computer science at Hampshire College.

Paul Sawaya is a software developer currently working on Restatement, an open source toolkit to parse, manipulate, and publish legal documents on the web. He previously worked on identity at Mozilla, and studied computer science at Hampshire College.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.