As guest bloggers to this site, we have been asked to write about big ideas. We’ll get to those. But first, a note about hackathons.

Could legal hackathons be like this one day?

Hackathons used to be the exclusive domain of soda-and-coffee-guzzling, pizza-eating, all-night hacking, highly competitive computer programmers. The result of such a hackathon is often supposed to be a cool app (like the forerunner of Twitter) that is even cooler because it was built in the compressed schedule of the event. More recently, hackathons have been popping up in a variety of places, with some unexpected contexts and sponsors including the U.S. House of Representatives, NASA, Brooklyn Law School, New York City government, and others. These events serve as a way to prove (or build) the sponsor’s tech credentials and to cross-fertilize policy and technology expertise. There has been some handwringing and thoughtful commentary about the expansion of “civic” hackathons and what sustainable outcomes they produce.

As co-organizers, with Karen Suhaka, Greg Wilson, Charles Belle and others, of two legislative focused, hackathon-inspired events–the California Law Hackathon, and the International Legislation Un-hackathon–we can attest to their value in bringing engineers and lawyer and policy folks together. We can give some insights into the kinds of benefits these events have had in propelling efforts on legislative data standards, and some of the advances that have taken place in the development of these standards over the last year.

Big Idea: Legislative Data Standards

And now to the big idea: to represent all the world’s legislation in a standard structured data format. That’s actually two big ideas: (1) putting legislation into a structured data format, and (2) designing that format so that it is compatible with the wide variety of laws and legislative document types worldwide.

There are reasons for doing these things: First, introducing structured data to legislation can make it possible to search and analyze the law with greater precision and efficiency. And second, having a common standard can permit more comprehensive bill-tracking and comparison between jurisdictions.

It also can make it possible for legislatures with small (and shrinking) budgets to benefit from some of the same bill drafting software that is being developed for much larger jurisdictions. (Full disclosure: Xcential has developed such software for more than ten years, including the drafting platform used by the State of California.)

In the age of Google, these ideas may not seem so big; in fact, they are a subset of Google’s far-reaching mission. However, legislation is a corner of the world’s information that Google has not yet addressed in a systematic way. And as regular readers of this blog know, legislation presents its own hurdles, technical and bureaucratic (not necessarily in that order), that make this both an interesting and a challenging problem. One of the challenges is that the kind of people who generally work with data (we’ll call them engineers) and the kind of people who generally work with legislation (we’ll call them lawyers and policy folks) don’t often work on data and legislation together. One of us, a lawyer and policy type, has made this point graphically (and somewhat hyperbolically) in a Quora response to a question about whether version control software could be used for legislation. That question, and a subsequent discussion generated in response to a blogpost by software engineer Abe Voelker about version control for legislation, drew in many engineers and some lawyers and policy folks.

For software engineers who consider such things, it is very attractive to think about treating legal text as if it were software code; we could automatically highlight and cross-validate key terms, run test cases, automate redlining and version control, etc. It would be easy to see what the state of the law was at any particular point in time, and to trace the series of amendments that got us into the mess we’re in today. This desire is often expressed as “What if we had a Github for legislation?” On the other hand, people who work closely with legislation–researching it, drafting it or developing information systems to deal with it–tend to see the many places that the analogy between computer code and legal code break down. Legal texts have been shaped over hundreds of years by technologically conservative institutions, using print-based systems.

The full transformation of law to digital information is not going to happen overnight. While most law is already accessible in electronic format (often pdf), it is not encoded in a way that software engineers could start using their favorite text-munching tools. One of us, an engineer, has described this as the difference between computerization and automation. The move toward better digital tools for automating legislative drafting and research tasks will require more dialogue and working exchanges between engineers and the lawyers and policy folks.

That brings us back to hackathons.

What is a Legislative Hackathon?

Recognizing the need to bring lawyers and engineers together in order to implement our big idea(s), and appreciating the valuable bandwagon that hackathons have become, we decided to jump onboard. The first event we organized, the California Law Hackathon, was hosted just over a year ago, in September 2011, in Berkeley at the offices of Maplight, and in Denver by Karen Suhaka’s team at BillTrack50. The event focused on building web-based visualization tools to track the timeline of amendments to California legislation, and to link particular amendments, through their legislative sponsors, to particular donors or interest groups. We were joined remotely by a number of international participants, including John Sheridan, head of e-services for legislation.gov.uk, and a fellow guest contributor to this blog. As one participant noted, we learned a great deal at the event, including the limits placed on us by the existing data. Neither the legislative record, nor the donations databases are detailed enough to trace influence in politics in the way we hoped. This helped spark an interest in a more in-depth exploration of legislative data formats, and in particular how more and better metadata could be added to legislation.

That led to the International Legislation Un-hackathon, held simultaneously at UC Hastings, Stanford and Denver, with participants from the University of Bologna (Ravenna campus) and around the world. So assuming you can get engineers together with lawyers and policy folks, what do you do with them? We decided that we’d need a user-friendly tool that could be used to explore and add metadata to legislation from around the world. This could highlight a developing legislative XML standard, Akoma Ntoso (more about this standard soon), and give hands-on experience to lawyer and policy types kinds of text and analysis tools that engineers take for granted.

Hacking With A Legislative Editor

So one of us (the engineer, naturally) started building a web-based editor for legislation, while the other (the lawyer, naturally) started organizing the next hackathon. Of course, thought the lawyer, it would just

be a matter of time before all governments worldwide use such editors to draft their laws and regulations in a standard data format.

Advances in Legislative Data Standards Efforts

Akoma Ntoso

Akoma Ntoso (AkN) is a strong contender to be that format. Developed under the auspices of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, AkN is an XML data structure that is meant to capture high-level forms and semantic ideas that are common to a broad variety of legal texts. OASIS, the folks who brought us the DocBook standards, among others, have convened a standards committee to create an official legislative data standard based on AkN. (More disclosure: the engineer is a member of this committee.) There’s just one problem. Few governments are using AkN to draft or store their legislation.

AkN itself is fast evolving, and with more exposure to legal data structures from different jurisdictions, the OASIS committee will be able to adapt AkN to better model those structures.

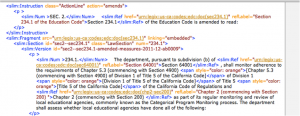

We saw the International Legislative Un-Hackathon as a venue to kick off this process. It was conceived with Charles Belle of UC Hastings, as part of the Legal Hacks initiative. The event was held simultaneously at UC Hastings, Stanford, in Denver. Jim Harper and Francis Avila of the Cato Institute came to the Hastings Event. We also had many international participants. Key among them were Professors Monica Palmirani and Fabio Vitali of the University of Bologna, the architects and primary evangelists of AkN. Over the course of the day, participants learned about AkN and, importantly, got a chance to try it out, marking up documents of their choosing with the web editor. In the process, as expected, we found bugs in the software and bugs in the standard. We found structures in U.S. legislation that didn’t fit well with the existing AkN element set. We saw places where there was confusion in applying AkN’s data structures to documents. All of this information was collected to incorporate in the development of both the editor and AkN, underscoring again the importance of getting more practical exposure for both.

University of Bologna Summer School–Ravenna

And we are working to expand the venues for this kind of practical exposure to develop the AkN standard. Every September, the University of Bologna hosts the LEX Summer School in Ravenna, Italy. For them, it’s an opportunity to introduce Akoma Ntoso to new groups of students from around Europe and around the world. For the students, it’s an opportunity to learn about the application of XML to legislation, see the success various groups are having around the world, and to meet interesting new people having a passion for legal informatics. One of us, the engineer, who was a student two years ago, was invited to return last year to present a success story, and this year is returning once more to deliver a class in how to build and use the HTML5-based editor for drafting legislation in XML. For us, this is an opportunity to expose the editor to the European legal traditions in order for us to better understand how our editor must evolve to fulfill our vision of a unified standard around the world with common, highly adaptable, tools.

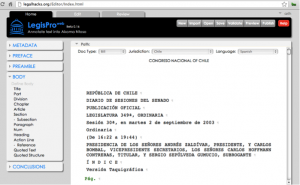

Chile National Library of Congress Browser-based editor

Another step toward adoption of legislative data standards is a project by Chile’s National Library of Congress (BCN in Spanish) called the “History of the Law” (Historia de la Ley). This ambitious project aims to bring together machine learning, a legislative editor and other features to mark up Chile’s legislative record and other legislative documents. The BCN has chosen Xcential’s browser-based editor, working with the AkN standard, to conduct the mark-up and correction after documents are passed through an automated parser. As with the hackathon, but on a larger scale, we are learning from experience the modifications that are needed to AkN, to make it work with Chile’s live documents. Excitingly, each mismatch we find between AkN and actual legislation can be fed back into the OASIS committee process, to make AkN able to handle a wider variety of real-world use cases.

Other Efforts and the Future of Legislative Data Standards

We see these steps as just the beginning. European governments are also flirting with legislative standards, and Karen Suhaka’s group at BillTrack50 has converted all U.S. bills from all states into a single standard XML format showing that the technical hurdles can be overcome, and many of the practical benefits of doing so. In focusing on the projects (and hackathons) we are most closely involved with, we have certainly left out a lot of the initiatives that are advancing legislative data standards around the world. That’s what the comments are for. Let us know your experience with Akoma Ntosa as a legislative standard, and what you’re doing or interested in doing with AkN or other legislative data standards worldwide.

Grant Vergottini (the engineer) is a founder of Xcential. He is a leading authority on applications of XML data to legislation. Prior to founding Xcential, Grant was the Director of Applications at Chrystal Software, a company dedicated to XML design and reporting software. Before Chrystal, Grant led the redesign of Homestore.com, and founded Genedax Design Automation, which developed innovative team and data management applications for electronics design. Bringing data structures and automation tools to the legislative drafting process parallels the work that Grant did earlier in his career at Mentor Graphics and the Boeing Company, where he participated in the transformation from manual drafting to CAD software. Mr. Vergottini holds a Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering from Cleveland State University, where he graduated Summa Cum Laude.

Grant Vergottini (the engineer) is a founder of Xcential. He is a leading authority on applications of XML data to legislation. Prior to founding Xcential, Grant was the Director of Applications at Chrystal Software, a company dedicated to XML design and reporting software. Before Chrystal, Grant led the redesign of Homestore.com, and founded Genedax Design Automation, which developed innovative team and data management applications for electronics design. Bringing data structures and automation tools to the legislative drafting process parallels the work that Grant did earlier in his career at Mentor Graphics and the Boeing Company, where he participated in the transformation from manual drafting to CAD software. Mr. Vergottini holds a Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering from Cleveland State University, where he graduated Summa Cum Laude.

Ari Hershowitz (the lawyer) is a consultant at Xcential, and founder of Tabulaw. Tabulaw develops software for lawyers, including a web-based legal research and writing platform. Prior to Tabulaw, Ari worked to protect wildlife and habitats from Chile to Mexico as Director of the BioGems project for Latin America at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Ari has a law degree from Georgetown University Law Center, a Masters in Computation and Neural Systems from Caltech, and a Bachelors in Molecular Biophysics & Biochemistry from Yale College.

Ari Hershowitz (the lawyer) is a consultant at Xcential, and founder of Tabulaw. Tabulaw develops software for lawyers, including a web-based legal research and writing platform. Prior to Tabulaw, Ari worked to protect wildlife and habitats from Chile to Mexico as Director of the BioGems project for Latin America at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Ari has a law degree from Georgetown University Law Center, a Masters in Computation and Neural Systems from Caltech, and a Bachelors in Molecular Biophysics & Biochemistry from Yale College.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.

[Editor’s Note: For topic-related VoxPopuLII posts please see: Núria Casellas, Semantic Enhancement of legal information … Are we up for the challenge?; João Lima, et.al, LexML Brazil Project; and Rinke Hoekstra, The MetaLex Document Server

The biggest advantage of established legal publishing houses, as opposed to new start-ups, is their brand recognition, and the chance to position themselves as gatekeepers for high quality information. The corresponding threat is –- again –- based on new technologies: Services such as

The biggest advantage of established legal publishing houses, as opposed to new start-ups, is their brand recognition, and the chance to position themselves as gatekeepers for high quality information. The corresponding threat is –- again –- based on new technologies: Services such as

In 2004,

In 2004,  Courts have gradually been adopting the neutral citation, beginning in 1999 and continuing to the present. The first adopter of the neutral citation was the

Courts have gradually been adopting the neutral citation, beginning in 1999 and continuing to the present. The first adopter of the neutral citation was the