The other day a friend came to me because he heard about the openlaws.eu project. He said: “Hey, openlaws sounds great – does that mean that I can write my own laws now?”. I had to tell him no, but that it was almost as good as that… Continue reading »

VoxPopuLII

openlaws

Accessible Law

Professor Richard Leiter, on his blog, The Life of Books, poses The 21st Century Law Library Conundrum: Free Law and Paying to Understand It:

The digital revolution, that once upon a time promised free access to legal materials, will deliver on that promise; it’s just that the free materials it will deliver, even if it comprises the sum total of all primary law in the country at every level and jurisdiction, will amount to only a minor portion of the materials that lawyers need in order to practice law, and the public needs in order to understand it.

This article explores what more we need in order to understand the law and how this need can be met, from a UK perspective.

Free acce ss to law

ss to law

Free access to primary law is of course a prerequisite for the interpretation and understanding of the law. In the UK and most countries with a common law tradition, the cause of free access to law is espoused by the Free Access to Law Movement, a collective of legal information institutes that began with the creation of the Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute (LII) in 1992. In the UK we are represented by the British and Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII), set up in 2000 with the enormous help of the pioneering Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII). In October 2002, at the 4th Law via Internet Conference in Montreal, the LIIs published a joint statement of their philosophy of access to law in the following terms:

Legal information institutes of the world, meeting in Montreal, declare that,

- Public legal information from all countries and international institutions is part of the common heritage of humanity. Maximising access to this information promotes justice and the rule of law;

- Public legal information is digital common property and should be accessible to all on a non-profit basis and free of charge;

- Independent non-profit organisations have the right to publish public legal information and the government bodies that create or control that information should provide access to it so that it can be published.

So, to paraphrase liberally, we have a right to access the laws of our land, free of charge and openly licensed. “The problem for aggregators like LII,” Leiter points out, “is that the information that they provide is only as good as the sources available to them. And governments are just not very good sources of their own information.” In the US, Law.Gov is a movement working to raise the quality of government information, proposing a distributed repository of all primary legal materials of the United States. It believes that “the primary legal materials of the United States are the raw materials of our democracy. They should be made more broadly available to enable an informed citizenry,” and that “governmental institutions should make these materials available in bulk as distributed, authenticated, well-formatted data.” In other words, we need more than free access to law; we need free access to good law data.

UK legislation

In the UK we were fortunate that the previous administration’s Power of Information agenda was being implemented by the Office of Public Sector Information (OPSI), whose role also includes that of Queen’s Printer (of legislation). In December 2006, the long-awaited Statute Law Database (SLD) had been published, having been more than 10 years in development. This provided (subject to a number of shortcomings) point-in-time access to all in-force UK primary legislation since the year dot (forever), and access to all secondary legislation published since 1991. Responsibility for the SLD then lay with the Statutory Publications Office (SPO), part of the Ministry of Justice. In 2008 the decision was taken to merge the SPO into OPSI, who had been publishing all as-enacted legislation since 1988. The merger would bring the online legislative services together, creating a single place where visitors could access the widest range of legislative content held by the government, alongside supporting material. That service is Legislation.gov.uk, launched in July 2010, which has now replaced the SLD and OPSI legislation services.

The Legislation.gov.uk interface provides simple and direct browse access to legislation by type, year and number, and simple or advanced searches to locate matching legislation. Primary legislation can be viewed as at any point in time since 1991. More important than this improved access to legislation, however, is the fact that the content is open. It is all well-structured XML; any piece of legislation or legislation fragment can be addressed reliably and simply in various useful formats via the URI scheme; and any list of legislation resulting from a query can be delivered as an Atom feed. And a new licensing model for public sector information (which in the UK is subject to Crown copyright) was introduced at the same time – the Open Government Licence.

Unfortunately, there are insufficient government resources to maintain an up-to-date, consolidated statute book, as Shane O’Neill observes:

The lack of up-to-date consolidation – no fault of the Legislation.gov.uk team who have laboured valiantly on their Sisyphean task – must be a concern to those who harboured greater ambitions (not least Government and judiciary). It leaves access to an up-to-date and consolidated statute book in the hands of those who have invested in and deliver highly exclusive legal information services [Westlaw/LexisNexis – hereafter Wexis].

The Legislation.gov.uk service is delivered by The National Archives (of which OPSI is part) with John Sheridan, Head of e-Services and Strategy, at the helm. John describes the development in some detail in an earlier post on VoxPopuLII:

We had two objectives with legislation.gov.uk: to deliver a high quality public service for people who need to consult, cite, and use legislation on the Web; and to expose the UK’s Statute Book as data, for people to take, use, and re-use for whatever purpose or application they wish.

There’s more about the technical project and the people behind it from Jeni Tennison, technical lead and main developer (at TSO), on her blog. John is also on the expert panel of technologists advising the government on making public sector information more open and accessible on the Web, an initiative which led to the development of data.gov.uk, which currently provides access to over 5,600 central government datasets.

UK case law

Unfortunately, the public provision of case law in the UK is woefully inadequate, and we have to rely on the efforts of BAILII (a charity) to collate and deliver anything approaching a comprehensive collection of recent judgments. BAILII does a grand job in the circumstances, but – through no fault on its part – it is not comprehensive and it is not open. The various courts all publish their judgments in their own fashion, with no consistency of approach; in fact the High Court of England and Wales does not publish its own judgments at all, but passes selected handed-down judgments to BAILII to publish. To make matters worse, our right to access this case law is far from clear. There is some argument whether judges are public servants or not and hence whether their judgments are public sector information or not. In addition, regarding older judgments, the low level of originality required for copyright protection in the UK means that almost all older cases are copyright of either the transcriber or the reporter (or the publisher who commissioned them).

Understanding the law

Does free access to law or, even better, free access to good law data, make the law accessible? Will it empower the average citizen? Unfortunately not. As Leiter says, it is only a fraction of what lawyers need to practice law and the public needs to understand it. The law is not practically accessible: it is difficult to identify, obtain and understand legal resources, and they are frequently out of date. Whilst it is reasonable to expect legal advisers to invest in the necessary commercial services to inform themselves, these services are becoming increasingly unaffordable for the less affluent law practices and third sector advice bodies. For the non-lawyer, the law is all but impenetrable, and solving many legal problems and resolving disputes is in practice affordable only to the rich or those who are eligible for some kind of state support. Lord Justice Toulson in R v Chambers [2008] EWCA Crim 2467 famously bemoaned the complexity of legislation:

To a worryingly large extent, statutory law is not practically accessible today, even to the courts whose constitutional duty it is to interpret and enforce it. There are four principal reasons. … First, the majority of legislation is secondary legislation. …Secondly, the volume of legislation has increased very greatly over the last 40 years …Thirdly, on many subjects the legislation cannot be found in a single place, but in a patchwork of primary and secondary legislation. … Fourthly, there is no comprehensive statute law database with hyperlinks which would enable an intelligent person, by using a search engine, to find out all the legislation on a particular topic.

The give-us-the-data-and-we’ll-organise-the-world crowd also display a touching naïvety when it comes to the law. For example, on the launch of Legal Opinions on Google Scholar, Anurag Acharya, “Distinguished Engineer” at Google, said:

We think this addition to Google Scholar will empower the average citizen by helping everyone learn more about the laws that govern us all. … we were struck by how readable and accessible these opinions are. Court opinions don’t just describe a decision but also present the reasons that support the decision. In doing so, they explain the intricacies of law in the context of real-life situations.

Any initiative that makes the law more accessible is to be welcomed, but to empower the average citizen you have to go the extra mile, by explaining the law. Lawyers and legal researchers have spent years learning the law and acquiring the skills that enable them to navigate and reliably interpret primary law and precedent. They will find value in free access to law and in Google Scholar and other free services that are built on that, but they and the average citizen need more. That need is met largely by commercial publishers, and, while there many smaller independent publishers who provide good value in their niches, as O’Neill observes:

Legal publishing has long been dominated by two huge duopolists (Reed Elsevier’s LexisNexis and ThomsonReuters) whose scale alone enables them to provide a consolidation of the mix of primary, secondary, case law which characterises our common law system. This has created what [barrister Francis Davey] in The Times on 23 May 2006 characterised as “a two-tier justice system with only the very rich able to access the full consolidated law while those lawyers doing pro bono work are discriminated against.”

But there is an increasing amount of quality free legal commentary and analysis on the Web, and we can dream on.

The law wiki dream

Writing in Times Online in April 2006, the eminent Professor Richard Susskind, legal tech guru and adviser to the great and good, spelt out his vision for a “Wikipedia of English law”:

This online resource could be established and maintained collectively by the legal profession; by practitioners, judges, academics and voluntary workers. If leaders in the English legal world are serious about promoting the jurisdiction as world class, here is a genuine opportunity to pioneer, to excel, to provide a wonderful social service, and to leave a substantial legacy. The initiative would evolve a corpus of English law like no other: a resource readily available to lawyers and lay people; a free web of inter-linked materials; packed with scholarly analysis and commentary, supplemented by useful guidance and procedure; rendered intensely practical by the addition of action points and standard documents; and underpinned by direct access to legislation and case law, made available by the Government, perhaps through BAILII. … A Wikipedia of English law could be an evolving, interactive, multimedia legal resource of unprecedented scale and utility.

Susskind referred specifically to wikis and “a Wikipedia,” and that was taken rather literally by those who enthusiastically first took up his challenge. But I don’t believe he necessarily intended it literally, and I don’t believe that “a Wikipedia” or indeed the wiki platform is appropriate. Wikipedia has to be seen as a one-off; no wiki project since has come anywhere near its scale or success. We are most unlikely to build an encyclopedia of UK law from scratch; but why would we try when there is already a vast free legal web?

The free legal web

In 2008, enthused by the developments in open government and by the amount of quality legal commentary that was percolating up on the Web, I proposed to set up a service to exploit this – FreeLegalWeb. In the manifesto I listed the free access law resources then available, and I now list them with appropriate updates, here:

- We have [free and open access to legislation]

- [We have] other official documents, forms and guidance from government and a commitment to making these resources more accessible and encouraging user generated services.

- We have another substantial free access primary law database – BAILII.

- We have a number of specialists already maintaining specialist law wikis and enthusiasts contributing law articles to Wikipedia.

- We have a growing number of law bloggers, many of whom provide succinct, expert ongoing commentary and analysis.

- We have many other individuals, firms and publishers who publish case summaries, articles, updaters and guidance for free access on their websites.

- We have public, charitable and private services providing free guidance and fora for the public faced with legal processes.

- And finally, we have Web 2.0 technologies that enable (potentially) all these sources to be interrogated, aggregated, “mashed up” and repurposed.

That sounded like a free legal web to me; all we had to do was join it up and curate it! But how feasible is that?

A “bunch of goo”?

Bob Berring, legal research guru and Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley, gave his thoughts on the matter  on YouTube in October 2009. He believes that government efforts in the provision of free legal information have failed because there are no incentives; and that “volunteer efforts”, worthy as they may be, are unlikely to be sustained. He rightly says that legal information is not easily packaged: we need a map and a compass to navigate it; it needs to be organised and value added. I think we all agree with that. But his conclusion appears to be that only Wexis have sufficient incentive and only they can mobilise the necessary army to add sufficient value for it to be useful. For Bob, the free legal information that’s out there is “a bunch of goo,” and the only thing that can sort out the mess is “the market system”. That’s clearly not the case:

on YouTube in October 2009. He believes that government efforts in the provision of free legal information have failed because there are no incentives; and that “volunteer efforts”, worthy as they may be, are unlikely to be sustained. He rightly says that legal information is not easily packaged: we need a map and a compass to navigate it; it needs to be organised and value added. I think we all agree with that. But his conclusion appears to be that only Wexis have sufficient incentive and only they can mobilise the necessary army to add sufficient value for it to be useful. For Bob, the free legal information that’s out there is “a bunch of goo,” and the only thing that can sort out the mess is “the market system”. That’s clearly not the case:

- government has an incentive to make legal information more accessible

- the legal profession has an incentive to make legal information more accessible

- various non-profits have an incentive to make legal information more accessible

- citizens have an incentive to make legal information more accessible

- and there are many private enterprises short of Wexis who have an incentive to make legal information more accessible.

… How?

Curating the legal web

For help I’m increasingly turning to Jason Wilson, Vice President at Jones McClure Publishing. He has a nice clean minimalist blog with great pics accompanying each post. More importantly, he’s interested in the kind of questions I’m also trying to answer, such as: Can we crowdsource reliable analytical legal content?

I have given considerable thought to this problem (and I have a greater interest in solving it than most), and I just don’t see how a Demand Media or similar model could ever produce good or reliable analytical material.

But in the next breath he acknowledges that a lot of good stuff has indeed already been generated by the crowds, and asks how we will organise that legal web. Actually the question is buried at the end of a dense post about “exploded data” (the value of analytical content):

My thought at this point is that the legal web is in an infancy that we can’t even fathom yet. There is cloud of associated information that our current computer assisted legal research vendors cannot give to us based on their algorithms, especially when they remain in walled-in gardens that don’t account for the vast and valuable information being created by users. The question is whether we will step up to organize this sea of data, or wait until a program can do it for us?

Moving on, in a more accessible post on Slaw he asks how we can effectively curate the legal web:

Curating this growing body of analytical content will be difficult. It suggests a person-machine process of locating and separating good content from bad, and categorizing, verifying, authenticating, and editorializing that content. It will undoubtedly require the creation of a rich taxonomy to help organize and manage the content for later discovery, clean metadata, and a good search engine, and raises issues from data permanency to copyrights to brand dilution. It’s a mess. But a worthy one I think.

and in the comments to that post:

I suppose the point to my post is whether we can wrap a wiki-like structure and interface around the legal web, and make it a destination for learning about both general topics and specific issues, rather than just a portal for all results that match search terms.

Yes we can! However clever the machine, these tasks – “locating and separating good content from bad, and categorizing, verifying, authenticating, and editorializing” – to a large degree require human intervention. But that intervention need only be light touch once we figure out how most effectively to harness the wisdom of the crowds.

Conclusion

Free access to law is not a panacea, but there is plenty of scope for delivering more accessible law by leveraging not just free law but the free legal web; for delivering free services that are good enough for the average citizen, and for lower cost commercial services that are good enough for the average lawyer. Big Law will continue to need Wexis, but the “lower-tier” can be much better served. The final word I will leave with Tom Bruce:

We need to make informed choices between inexpensive automated approaches that work by brute force and the hand-crafted, highly-accurate approaches of legal bibliography that are not always scalable or affordable. We need to recalibrate what we mean by “authority”, and begin to think about measures of quality and reliability for legal text that avoid the creation of unnatural monopolies in legal information.

[Editor’s Note: For more information on crowdsourcing legal commentary, please see Staffan Malmgren’s post. On using social media to enhance access to free legal resources, see Olivier Charbonneau’s post. On making primary law useable by non-lawyer citizens, see earlier posts by Judge Dory Reiling and Christine Kirchberger. For earlier replies to Bob Berring, see Tom Bruce’s responses here and here.]

Nick Holmes is a publishing consultant specialising in the UK legal sector and is Managing Director of legal information services company infolaw (infolaw.co.uk). He is also the founder of FreeLegalWeb CIC (freelegalweb.org).

Nick Holmes is a publishing consultant specialising in the UK legal sector and is Managing Director of legal information services company infolaw (infolaw.co.uk). He is also the founder of FreeLegalWeb CIC (freelegalweb.org).

Email: nickholmes [at] infolaw [dot] co [dot] uk. Twitter: @nickholmes.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor in chief is Robert Richards.

Context and Legal Informatics Research

[Editor’s Note: A slighly different version of this post was published on Slaw in May 2010. We thank Slaw‘s editor, Professor Simon Fodden, for granting permission to repost.]

The relationship of legal information to context is a key dimension of recent developments in legal informatics scholarship and innovation. These developments range from investigations in law and psychology to political and moral theory, from explorations in artificial intelligence and law to legal information theory, and from research on the legal Semantic Web to the creation of new applications that help nonlawyers contextualize legal information.

The relationship of legal information to context is a key dimension of recent developments in legal informatics scholarship and innovation. These developments range from investigations in law and psychology to political and moral theory, from explorations in artificial intelligence and law to legal information theory, and from research on the legal Semantic Web to the creation of new applications that help nonlawyers contextualize legal information.

Professor Helen Nissenbaum has foregrounded the notion of context in the debate over privacy respecting court records. In her new book, Privacy in Context, and in her presentation at the 2010 Princeton Open Government Workshop, Nissenbaum defines the right to privacy as the right to what she calls “contextual integrity,” meaning the use or “flow” of information consistent with the norm for information transfer applicable in the particular context — such as home, school, workplace, court, etc. — where the information was first transferred. For Nissenbaum, key characteristics of an information context — the sender of the information, the intended recipient of the information, the subject of the information, the type of information that is shared, and the purposes and goals served by the information context — determine which norm governs information flow in that context. In Nissenbaum’s view, when information about individuals flows in a manner consistent with its contextual norm, “contextual integrity” — and those individuals’ privacy rights — are considered to have been preserved, but if that information flows in a manner inconsistent with that norm, contextual integrity — and thus the privacy rights of those individuals — are considered to have been breached. Nissenbaum argues that when a new technology — such as a publicly available online database of court records — arises that arguably violates contextual integrity, a presumption should arise in favor of preserving contextual integrity and rejecting the new technology. On Nissenbaum’s account, that presumption may be rebutted if the new technology can be shown more effectively to serve both general social values such as social welfare and national security, and also the particular purposes and goals of the original information context. Nissenbaum allows that the new technology might also prevail if it, or some aspect of the information available through it, could be modified to render it superior in vindicating both general and contextual values. Applying Nissenbaum’s model to court records would thus entail a careful consideration of a variety of contexts in which those records are generated, the rejection of certain new information technologies, and also negotiations with technologists to determine whether certain new technologies, or the data they process, could be modified so as to render those technologies superior to the original systems in vindicating general and contextual values.

Professor Guido Boella, Dr. Guido Governatori, and colleagues are exploring ways to model legal contexts to aid automated legal reasoning. In their recent paper these scholars show how defeasible logic can be employed to represent the policy context of legal rules. Their approach could improve computers’ capacity to assess legal compliance, and could contribute to the automation of the interpretation of legal language.

In legal information retrieval, K. Tamsin Maxwell — in a recent post, as well as in a recent conference paper co-authored by Burkhard Schafer — is exploring the use of Natural Language Processing techniques to contextualize queries, automate discovery of factually-similar cases, and achieve “near perfect search recall within the context of precision.”

Recent research in law and psychology — particularly the research highlighted by The Situationist blog published by the Project on Law and Mind Sciences at Harvard Law School — emphasizes how context affects people’s understanding and use of legal information. For example, Professor Adam Benforado‘s new paper explores how spatial situations affect the law-related behavior and thinking of various participants in criminal cases, while another of his recent articles argues that the context of the videotape evidence at issue in Scott v. Harris had a profound and unacknowledged influence on the way the U.S. Supreme Court interpreted that evidence.

Recent research in law and psychology — particularly the research highlighted by The Situationist blog published by the Project on Law and Mind Sciences at Harvard Law School — emphasizes how context affects people’s understanding and use of legal information. For example, Professor Adam Benforado‘s new paper explores how spatial situations affect the law-related behavior and thinking of various participants in criminal cases, while another of his recent articles argues that the context of the videotape evidence at issue in Scott v. Harris had a profound and unacknowledged influence on the way the U.S. Supreme Court interpreted that evidence.

In her recent post and her dissertation in progress, Christine Kirchberger explores the importance of context for making legal information usable by nonlawyers. Kirchberger highlights legal Semantic Web technology — such as that discussed in Dr. Núria Casellas’s recent post on legal ontologies — and government eportals — like Austria’s HELP service — as promising means of offering valuable context to nonlawyers using legal information. Kirchberger quotes Tom Bruce‘s 2001 paper on the need to build flexible systems that can present legal information in a range of different contexts, suited to the needs of different users of those systems.

Some free access to law services are providing this kind of contextual information by building secondary sources into their systems. For example, the Cornell Legal Information Institute‘s Wex legal encyclopedia — written collaboratively by volunteers — explains key legal concepts and terms that appear in the Institute’s primary collections. As Staffan Malmgren explains in this recent post, his lagen.nu free access to law service for Sweden includes commentaries, written by means of an innovative crowdsourcing method.

Automatic linking is another method of furnishing context to users of legal information, as hotlinked citations enable quick retrieval of full text sources that make up legal context. Free access to law services such as CanLII provide such technology for linking to primary legal sources — as Ivan Mokanov explains in this recent post. In his recent thesis, conference paper, and post, Olivier Charbonneau proposes several ideas for delivering contextual information to users of free legal systems. These include personalized user interfaces; automatic display of citing sources when a cursor is placed over a passage of a primary legal document; automatic display of relevant commentaries below or alongside a primary legal text; and user ratings of user-contributed commentary, to help nonlawyers assess the quality of content.

Dr. Floris Bex in his recent dissertation and post explains how argument- and narrative-mapping technology can provide valuable context for prosecutors conducting criminal investigations. Dr. Bex describes his and his colleagues’ research — and particularly the work of Dr. Susan van den Braak — respecting a variety of applications that provide visual displays of investigators’ legal and factual arguments and narrative accounts of alleged crimes. These tools allow investigators to contextualize each relevant fact and point of law within a conceptual framework for their case.

Two current U.S. federal court technology efforts aim to help nonlawyers put legal information in context. JERS, the Jury Evidence Recording System, enables jurors in four U.S. federal district courts to view digital representations of trial evidence and exhibits in the jury deliberation room, and navigate through the information — including via zooming and scrolling — by means of video touchscreen. This access to evidentiary information not only helps each individual juror attain a contextual understanding of the applicable law and facts of the case; it also increases the likelihood that all members of a jury will share the same understanding of the context of the case. On April 27, 2010, the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts announced that funding for JERS had been renewed.

Two current U.S. federal court technology efforts aim to help nonlawyers put legal information in context. JERS, the Jury Evidence Recording System, enables jurors in four U.S. federal district courts to view digital representations of trial evidence and exhibits in the jury deliberation room, and navigate through the information — including via zooming and scrolling — by means of video touchscreen. This access to evidentiary information not only helps each individual juror attain a contextual understanding of the applicable law and facts of the case; it also increases the likelihood that all members of a jury will share the same understanding of the context of the case. On April 27, 2010, the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts announced that funding for JERS had been renewed.

Whereas JERS helps jurors place legal information in context, the E Pro Se document assembly application assists self-represented litigants in contextualizing such information. A customization of the A2J Author document assembly program created for use in law school clinics by CALI, the Center for Computer Assisted Legal Instruction, and the Chicago-Kent College of Law’s Center for Access to Justice and Technology, E Pro Se conducts automated interactive interviews with pro se litigants in U.S. federal district court — for purposes of gathering contextual information from the litigants — and then processes that information to assemble pleadings and other court papers for the litigants. E Pro Se is now available online from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri. According to The Third Branch, the federal district court in Minnesota has begun a pilot E Pro Se project, and such a project will shortly begin in the Massachusetts federal district court. (Thanks to CALI’s Executive Director John P. Mayer for information on this topic.)

Nonlawyers who participate in policy discussions about proposed laws also need context to understand those laws. Researchers participating in the EU’s IMPACT Project are creating tools to provide this context. These tools include argument mapping applications and Semantic Web technology — described in new papers by Professor Tom van Engers and Dr. Adam Wyner — for organizing policy discussions into subject-related threads, with visual displays of the reasoning underlying the arguments that make up the discussion, translation of policy arguments into the preferred language of each user, and Web 2.0 services facilitating users’ participation in the discussions.

Context thus appears to be a focal point for legal informatics research, at the levels of theory, policy, and systems development. Research activity in this area appears to be vigorous, and embraces many disciplines in addition to law, including computer science, philosophy, political science, psychology, linguistics, sociology, anthropology, and information science. As the disintermediation of legal information professionals, the unbundling of legal services, and the participation of citizens in policy- and lawmaking proceed, the need can only grow for greater knowledge of how context affects individuals’ understanding and use of legal information, and for systems that effectively provide nonlawyers with relevant legal contextual information.

Robert Richards, JD, MSLIS, MA, is an information and communications researcher, specializing in legal information and communication systems. He is based in Philadelphia. He is editor in chief of VoxPopuLII, writes the Legal Informatics Blog, and created and maintains the online bibliography Legal Information Systems & Legal Informatics Resources. He is the founder and administrator of the Legal Informatics Research Network, an online community for those studying or developing legal information systems. His most recent writings include What Is Legal Information?, a paper delivered at the 2009 University of Colorado at Boulder Conference on Legal Information, and Cost-Effective Research in U.S. Bankruptcy Law (2009). As of September 2010 he will be a Ph.D. student in the University of Washington Department of Communication.

Robert Richards, JD, MSLIS, MA, is an information and communications researcher, specializing in legal information and communication systems. He is based in Philadelphia. He is editor in chief of VoxPopuLII, writes the Legal Informatics Blog, and created and maintains the online bibliography Legal Information Systems & Legal Informatics Resources. He is the founder and administrator of the Legal Informatics Research Network, an online community for those studying or developing legal information systems. His most recent writings include What Is Legal Information?, a paper delivered at the 2009 University of Colorado at Boulder Conference on Legal Information, and Cost-Effective Research in U.S. Bankruptcy Law (2009). As of September 2010 he will be a Ph.D. student in the University of Washington Department of Communication.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt.

Crowdsourcing Legal Commentary

Background: The Need for Free Legal Commentaries

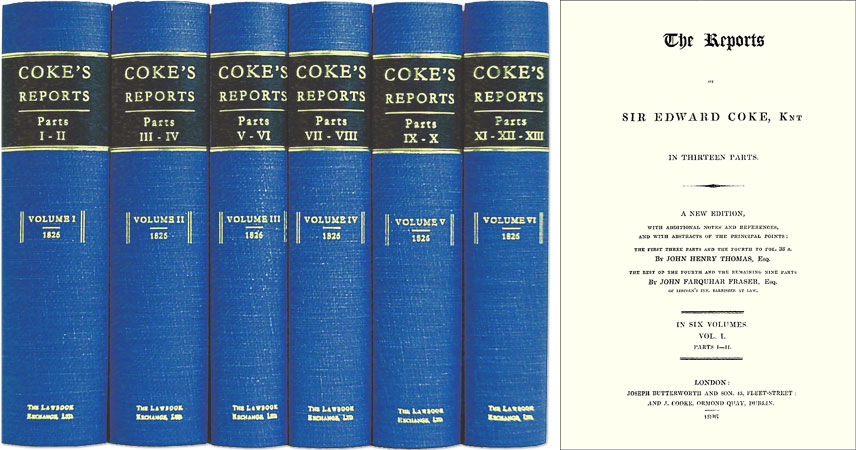

A legal commentary — also known as a legal treatise — is an unofficial text, intended to complement a particular source of law, often consisting of one or more statutes. A commentary on a statute provides information on how to interpret terms in the statutory text, summarizes examples of the statute’s application, references other relevant parts of the statutory law, and explains the legislative history and policy background of the statute. As statutory law is typically written in an open-ended way, setting forth norms in general language and usually without examples of how the law should be applied, a newcomer may have difficulty understanding it. Legal commentaries help with this.

In many jurisdictions, the texts of statutes are published by the legislature, usually without claim to copyright, and thus are made available to all, including to free-access-to-law services. Legal commentaries, by contrast, are written by private parties, who have a copyright on the resulting text, copies of which they typically sell at price levels that prevent most persons other than legal professionals from accessing them. Thus, most citizens may have free access to law, but not to the texts necessary for understanding it.

My background is that of a software developer, but in 2005 I started law school in Sweden. At that time, I couldn’t find any good freely accessible web service containing Swedish statutory law, so I built one called lagen.nu (which, translated, means “the law, now”). When the site debuted it contained around 4,000 pages of statutory law, and another 10,000 pages with headnotes on legal cases, with hyperlinks and cross-references. Over the next few years the site was gradually improved, with better hyperlinking of references, the addition of the full text of case law, and an improved graphical interface. The purpose of the site was and is to make law accessible to the common person. But making available official data such as statutory and case law can only get you so far, as there are many aspects of the law which are not apparent from the face of primary legal documents.

The Swedish legal system, like most civil law systems, is based more on statutory law than are most common law systems. Jurists in Sweden therefore spend much time interpreting statutory law. There are several publishers — including Thomson Fakta and Norstedts Juridik — that provide legal commentaries on Swedish central acts. The commentaries are written for legal professionals, which is evident in both the extent of the commentaries and their price. (As an example, the standard commentary on the Swedish code of judicial procedure fills four loose-leaf binders and costs 4435 SEK [$611 US].) As such, they are not accessible in any realistic sense to laypeople.

Therefore, I started thinking about how one could create a free commentary on Swedish law. Traditional commentaries require enormous resources, the most critical and expensive being the time of professors or other experts. Commentaries written for legal professionals generally fall into either of two categories: (1) in-depth works, or (2) practice tools. In-depth works — such as Fitger’s Rättegångsbalken — provide extensive treatment of the subject, delve deeply into the historical and teleological background of the regulation in question, and examine every conceivable exceptions-from-the-exception-to-the-rule detail. Those commentaries can be ten times the length of the actual statutory text, and are typically published in book form. In particular, they are written for readers who already understand the basic concepts and structure of the regulation, and who have time to dig deeper. For ordinary people, this level of detail is neither needed nor wanted.

In addition, there are practice tools, shorter commentaries more suited for the practicing lawyer who needs to quickly understand a particular regulation. These are still written for professionals, and are typically accessible as part of an electronic database subscription. Such subscriptions are priced far beyond the reach of non-professionals as well.

Thus neither form of commentary is written for laypeople, and neither is readily available to them. In order for the law to be accessible to all, it needs to be explained differently, and the explanation needs to be freely available. Writing this sort of commentary doesn’t require a tenured professor. In fact, the basic aspects of any central act can be adequately explained by any law student having the following two qualities:

a) A thorough understanding of the subject (for example, having taken the relevant course and having received a good grade); and

b) A talent for explaining complex things succinctly. At this, the student may even outdo the professor, as the student — having recently been a novice respecting the topic — will have a better understanding of how the subject is approached by someone new to it.

In any given act, there are a handful of key sections. A brief introduction to the act, combined with short explanations of these key sections, would be enough to create something useful to a nonlawyer. A person with a good knowledge of the act could write this in an evening. Something more extensive, like a basic commentary on the interesting parts of any central act, could be written in one or two weeks of work.

Still, there are a lot of central acts in Swedish law, and of only a few of these do I have extensive knowledge. Since I wouldn’t be able to write all the commentary myself, I’d have to create something that made it possible for people more knowledgeable than I to contribute their knowledge. Thus, the solution would have two aspects — one technological, one social. During the spring, summer, and autumn of 2009, we tried to create this solution.

extensive knowledge. Since I wouldn’t be able to write all the commentary myself, I’d have to create something that made it possible for people more knowledgeable than I to contribute their knowledge. Thus, the solution would have two aspects — one technological, one social. During the spring, summer, and autumn of 2009, we tried to create this solution.

Technology: Collaborative Writing Tools

In our proposed free online system, a commentary for a single act would normally contain a brief introduction to the act itself, followed by comments on the most important sections. A simple way to do this is to write the entire commentary as a single text document, divided into different parts, each referencing a particular section of the act. Acts in the Swedish law system can vary greatly in length, with some being only a sentence long, and some being over 100,000 words long and containing over 1000 different sections. However, the decision to use one single commentary text per act was made in order to keep things simple.

Swedish acts are typically divided into chapters, which are divided into sections (though for shorter acts, only sections are used). For example, the second section of the fourth chapter of an act is referenced as “4 kap. 2 §”. We adopted a convention of using such a reference as a header preceding the commentary for the referenced section.

Apart from headings, we tried to use as little formatting as possible. Basic bold and italics were desirable, as were different sorts of lists (ordered, unordered, and definition lists), but not things like multiple fonts or footnotes. Hyperlinks, both internal within the system and external to other web pages, were encouraged.

Apart from commentaries on the acts themselves, we wanted to be able to describe important concepts referred to in the acts. To write succinct explanations of statutes, one often has to refer to central legal concepts (such as “The rule of law“). If that reference can be linked to a page that describes the concept in greater detail, the commentary can be made shorter and the user can decide whether to follow the link if more explanation is needed. Furthermore, the concept can be referred to from multiple commentaries.

In order for the process to be as simple as possible, we needed a web-based editing system that didn’t require any particular piece of software on the user’s computer. We also didn’t want to spend significant time developing or customizing software.

The decision was made to use MediaWiki, the software behind Wikipedia, for the task. MediaWiki is a very robust and well developed piece of software with an active developer community. It’s also easy to extend with “hooks,” that is, small pieces of code that are configured to run in certain situations (such when a page is saved). Pages can be hyperlinked, and basic formatting such as headings and lists can be done using a simple markup language, normally referred to as “wikitext.”

As MediaWiki is based around the editing of pages, the commentary for each act in our system would take the form of a page, and the description for each legal concept would also constitute a page. In Swedish law, acts and ordinances are published in a collection called SFS (Svensk författningssamling). Each act or ordinance is given an identifying number: e.g., the public access to information and secrecy act is known as “SFS 2009:400”. In our free online system, this would correspond to a commentary page called SFS/2009:400.

Unlike Wikipedia, we did not want to use MediaWiki as the interface for the reader. The primary reason for this was that we wanted to present the statutory text and the commentary side-by-side. In order to do that, we needed to extract the text that we had edited using MediaWiki, split it up into commentaries for each individual section, and then weave the statutory text and the commentary text together. (Click here to see an example.)

The architecture of lagen.nu is such that no pages are ever created dynamically in response to a user’s request. Instead, everything is pre-rendered in the form of static HTML files on disc. This makes the site responsive even when running on modest hardware and under high loads. A hook was developed so that every time a wiki page in the main namespace was saved, a program to weave together that commentary text with the statutory text was run. The result was stored as a normal HTML file on disc.

Writing the program to do this weaving was not a trivial task. In particular, translating the minimalist wikitext markup into XHTML fragments proved to be difficult, and not all MediaWiki markup was supported. We also needed to do custom processing of the commentary text. Luckily, a library was found that parsed the MediaWiki markup and returned the equivalent XHTML markup. This library was extended in order to identify references to acts, sections, and legal cases present in the system. This enabled the commentary authors, who were not expected to learn advanced hyperlinking syntax, to just write normal legal prose, which was then linked automatically.

Using this setup, the editing process boiled down to these steps:

- Find the act to be commented on on the main site, and click the “edit commentary” link.

- This leads to a MediaWiki editing page — or, if the user is not logged in, to a login form.

- The user creates or edits the commentary, saving occasionally.

- When saving, the edit can be flagged as a “minor edit”. When this is the case, the weaving process is not run, enabling the user to save work that is still in progress without changing the contents of the main site.

- When the user is satisfied (which does not necessarily mean that he/she is altogether done with writing the commentary, just that it is in such a state that it can be published on the main site), the page is saved and the weaving process is run.

- The user can then check the main site and verify that the statutory text and the commentary text look OK side by side.

Social Aspects: Coordinating the Writing Effort

The plan was to get motivated law students to write the commentary for our free online system. We formed a group of 14 people, consisting mostly of law students, but including some practicing or retired lawyers. They were each given an assignment, normally consisting of a single act, and the instruction to write the best commentary on that act that they could fashion, within a 40 hour period. For some longer acts, this limit was extended to 60 or 80 hours. The authors retained copyright in their work, and were to receive attribution for it, but they agreed to license it under a Creative Commons license (specifically the CC-BY-SA license). They were also given a small monetary compensation for their work. The deadline for completing the writing assignments was set for October 1st.

At the start of summer 2009, we held an initial workshop where the motivation and impetus of the project were explained, and where people were given some hands-on instruction in how to write and edit commentary. For the rest of the summer, project members communicated using an email mailing list, together with occasional get-togethers on Saturdays at the central library in Stockholm.

During this time, the framework for writing, as well as the results, were constantly examined and improved. My roles were those of software developer (fine-tuning the weaving process), editor (suggesting improvements to individual commentaries as they were written), and project manager (gently reminding everyone of the impending October deadline).

It soon became apparent that everyone had his or her own idea of how commentaries should be written. In general, this diversity is a good thing — if everyone tries out their ideas, we can see what works and what doesn’t. However, if everyone is forced to invent their own wheels, progress is slow and resources that could be used for writing are wasted on other things.

Therefore, we wrote a style guide, containing basic guidelines with examples on how to write concisely and simply, how to refer and link to legal concepts and external resources, how to prioritize, whom to write for, and so on. A getting-started guide, and a shorter guide to MediaWiki markup, were also written.

During the writing period we were featured in the daily press, trade magazines and national radio. We were also nominated for a prize awarded by the Centre for Easy-to-Read.

Evaluation: Does It Work?

From July to September 2009, we commented on 17 acts, 1,200 individual sections, and 500 legal concepts, resulting in a total output of over 400 pages of text. A great amount of knowledge was created in an amazingly short time span. The quality assurance, which was done by me, proved to be an interesting challenge, as I’m not (as stated above) an expert on all of the acts for which commentaries were written. However, having taken basic classes on all the areas of law addressed by the commentaries, I was able to recognize most of the content of the commentaries (and to dig deeper if I found statements that seemed at odds with what I had learned). Overall, the quality of the commentaries was surprisingly high.

In conclusion, the commentary project has been a learning experience. Following the intensive activity of the summer and autumn, fewer commentaries have been added to the system. One reason for this might be that we no longer have the funds to pay authors. The monetary compensation was small but not insignificant. However, it seemed that the major incentives for authors were the opportunity to make law more accessible to others, as well as the chance to educate themselves by explaining the law to others. We have now enabled non-registered users to comment on the commentaries, using the Discussion namespace of MediaWiki. This way, we have identified and fixed many omissions and mistakes in the original commentaries.

One thing that seemed to work really well was the procedure of assigning work and following up on it. Writing a commentary on a long statute can be accomplished using free time over the course of a month or two. Setting a deadline, monitoring progress, and providing relevant feedback can serve as incentives for authors, too.

The commentaries produced by our project are written using best-efforts principles. There are no guarantees that the information in the commentaries is complete, updated, or even correct. However, having a principal author for each commentary gives that author an incentive to ensure the information in the commentary is as good as possible. Authors may use, and in fact have used, their commentaries as work samples. Even so, having someone other than the author read the text and provide feedback can improve the quality of a commentary as well.

With the commentary project, I feel we have proved that legal commentaries can be written in a crowdsourced way (even though we used monetary compensation to motivate our authors), and that wiki technology has the required capabilities, and is sufficiently user-friendly, for such an undertaking.

The next step for our commentaries project is to formalize and sustain an assignment and feedback workflow. This will require multiple project managers, and ideally some form of delegation of responsibility for different parts of the law. Further, I am confident that the project can be sustained using a voluntary framework. This remains to be proven, though.

Note: This project was supported by a grant from Internetfonden, for which we are eternally grateful.

![]()

Staffan Malmgren — the creator of the Swedish free access to law service lagen.nu — is a project manager at the Swedish Courts administration by day, working on coordinating the publishing of official legal information on the web, using structured and standardized formats (by night, he’s working on his final law school thesis, on the subject of jurisprudential relevance ranking in legal information systems).

Recent Posts

- The Balancing Act: Looking Backward, Looking Ahead

- 25 for 25: So What(‘s Next)?

- You with the law show?

- 25 for 25: City Miles, Jazz, and Beacons

- Deeply intertwingled laws

- 25 for 25: A Librarian’s Free Law Awakening

- A birthday message

- 25 for 25 – Documents to Data : A Legal Memex

- 25 for 25: Envisioning Free Access to Caselaw

- The debate on research quality criteria for legal scholarship’s assessment: some key questions