The other day a friend came to me because he heard about the openlaws.eu project. He said: “Hey, openlaws sounds great – does that mean that I can write my own laws now?”. I had to tell him no, but that it was almost as good as that… Continue reading »

VoxPopuLII

At my organization, the Sunlight Foundation, we follow the rules. I don’t just mean that we obey the law — we literally track the law from inception to enactment to enforcement. After all, we are a non-partisan advocacy group dedicated to increasing government transparency, so we have to do this if we mean to serve one of our main functions: creating and guarding good laws, and stopping or amending bad ones.

One of the laws we work to protect is the Freedom of Information Act. Last year, after a Supreme Court ruling provided Congress with motivation to broaden the FOIA’s exemption clauses, we wanted to catch any attempts to do this as soon as they were made. As many reading this blog will know, one powerful way to watch for changes to existing law is to look for mentions of where that law has been codified in the United States Code. In the case of the FOIA, it’s placed at 5 U.S.C. § 552. So, what we wanted was a system that would automatically sift through the full text of all legislation, as soon as it was introduced or revised, and email us if such a citation appeared.

One of the laws we work to protect is the Freedom of Information Act. Last year, after a Supreme Court ruling provided Congress with motivation to broaden the FOIA’s exemption clauses, we wanted to catch any attempts to do this as soon as they were made. As many reading this blog will know, one powerful way to watch for changes to existing law is to look for mentions of where that law has been codified in the United States Code. In the case of the FOIA, it’s placed at 5 U.S.C. § 552. So, what we wanted was a system that would automatically sift through the full text of all legislation, as soon as it was introduced or revised, and email us if such a citation appeared.

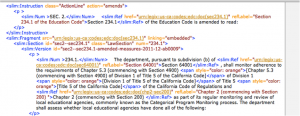

With modern web technology, and the fact that the Government Printing Office publishes nearly every bill in Congress in XML, this was actually a fairly straightforward thing to build internally. In fact, it was so straightforward that the next question felt obvious: why not do this for more kinds of information, and make it available freely to the public?

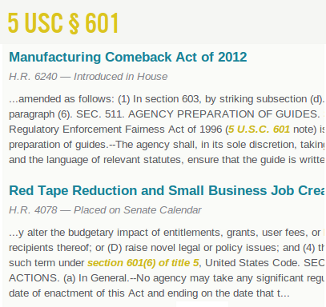

That’s why we built Scout, our search and notification system for government action. Scout searches the bills and speeches of Congress, and every federal regulation as they’re drafted and proposed. Through the awe-tacular power of our Open States project, Scout also tracks legislation as it emerges in statehouses all over the country. It offers simple and advanced search operators, and any search can be turned into an email alert or an RSS feed. If your search turns up a bill worth following, you can subscribe to bill-specific alerts, like when a vote on it is coming up.

This has practical applications for, really, just about everyone. If you care about an issue, be it as an environmental activist, a hunting enthusiast, a high (or low) powered lawyer, or a government affairs director for a company – finding needles in the giant haystack of government is a vital function. Since launching, Scout’s been used by thousands of people from a wide variety of backgrounds, by professionals and ordinary citizens alike.

Search and notifications are simple stuff, but simple can be powerful. Soon after Scout was operational, our original FOIA exemption alerts, keyed to mentions of 5 U.S.C. § 552, tipped us off to a proposal that any information a government passed to the Food and Drug Administration be given blanket immunity to FOIA if the passing government requested it.

Search and notifications are simple stuff, but simple can be powerful. Soon after Scout was operational, our original FOIA exemption alerts, keyed to mentions of 5 U.S.C. § 552, tipped us off to a proposal that any information a government passed to the Food and Drug Administration be given blanket immunity to FOIA if the passing government requested it.

If that sounds crazily broad, that’s because it is, and when we in turn passed this information onto the public interest groups who’d helped negotiate the legislation, they too were shocked. As is so often the case, the bill had been negotiated for 18 months behind closed doors, the provision was inserted immediately and anonymously before formal introduction, and was scheduled for a vote as soon as Senate processes would allow.

Because of Scout’s advance warning, there was just barely enough time to get the provision amended to something far narrower, through a unanimous floor vote hours before final passage. Without it, it’s entirely possible the provision would not have been noticed, much less changed.

This is the power of information; it’s why many newspapers, lobbying shops, law firms, and even government offices themselves pay good money for services like this. We believe everyone should have access to basic political intelligence, and are proud to offer something for free that levels the playing field even a little.

Of particular interest to the readers of this blog is that, since we understand the value of searching for legal citations, we’ve gone the extra mile to make US Code citation searches extra smart. If you search on Scout for a phrase that looks like a citation, such as “section 552 of title 5”, we’ll find and highlight that citation in any form, even if it’s worded differently or referencing a subsection (such as “5 U.S.C. 552(b)(3)”). If you’re curious about how we do this, check out our open source citation extraction engine – and feel free to help make it better!

It’s worth emphasizing that all of this is possible because of publicly available government information. In 2012, our legislative branch (particularly GPO and the House Clerk) and executive branch (particularly the Federal Register) provide a wealth of foundational information, and in open, machine-readable formats. Our code for processing it and making it available in Scout is all public and open source.

Anyone reading this blog is probably familiar with how easily legal information, even when ostensibly in the public domain, can be held back from public access. The judicial branch is particularly badly afflicted by this, where access to legal documents and data is dominated by an oligopoly of pay services both official (PACER) and private-sector (Westlaw, LexisNexis).

It’s easy to argue that legal information is arcane and boring to the everyday person, and that the only people who actually understand the law work at a place with the money to buy access to it. It’s also easy to see that as it stands now, this is a self-fulfilling prophecy. If this information is worth this much money, services that gate it amplify the political privilege and advantage that money brings.

The Sunlight Foundation stands for the idea that when government information is made public, no matter how arcane, it opens the door for that information to be made accessible and compelling to a broader swathe of our democracy than any one of us imagines. We hope that through Scout, and other projects like Open States and Capitol Words, we’re demonstrating a few important reasons to believe that.

Eric Mill is a software developer and international program officer for the Sunlight Foundation. He works on a number of Sunlight’s applications and data services, including Scout and the Congress app for Android.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.

[Editor’s Note: For topic-related VoxPopuLII posts please see, among others: Nick Holmes, Accessible Law; Matt Baca & Olin Parker, Collaborative, Open Democracy with LexPop; and John Sheridan, Legislation.gov.uk

When I started to write a post about THOMAS and its place in open government about three months ago, I was feeling apologetic. I was going make a heavy-handed, literal comparison of the opening hours of the Law Library of Congress (one of the maintainers of THOMAS, and my former employer, whose views are not at all represented here) with open government. I planned to wax sympathetic on the history of THOMAS, and how little has changed since it was first built. But, that post would not have added anything new to the #opengovdata conversation, or really mentioned data at all.

Just over one month ago, #freeTHOMAS reached a fever pitch surrounding the passage of H.R. 5882, the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act for FY2013. Just before passage, H.Rpt.511 directed official conversation on open legislative data for the coming fiscal year by saying, “let’s talk.” In a section about the Government Printing Office, the House Appropriations Committee expressed concerns about authentication and open legislative data, but called for a task force “composed of staff representatives of the Library of Congress, the Congressional Research Service, the Clerk of the House, the Government Printing Office, and such other congressional offices as may be necessary,” to look in to the matter.

Just over one month ago, #freeTHOMAS reached a fever pitch surrounding the passage of H.R. 5882, the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act for FY2013. Just before passage, H.Rpt.511 directed official conversation on open legislative data for the coming fiscal year by saying, “let’s talk.” In a section about the Government Printing Office, the House Appropriations Committee expressed concerns about authentication and open legislative data, but called for a task force “composed of staff representatives of the Library of Congress, the Congressional Research Service, the Clerk of the House, the Government Printing Office, and such other congressional offices as may be necessary,” to look in to the matter.

Opengovdata was disappointed in government. The tone of the House Report suggested that government had been dismissive of opengovdata–and in all fairness, others were beginning to be dismissive of opengovdata as well.

But, a clear classification problem was emerging. Inspired by Lawrence Lessig’s Freedom To Connect speech at the AFI in late May, I had a very librarian moment on organizational hierarchies.

#OpenGov is a really big tent.

People who want a more open environment for government to communicate with the governed want data, increased transparency, plain language legislation, open court filings, access to government funded research, silly walks, etc. Accountability through transparency often dominates the conversation, thanks to well-funded non-profits and high profile projects. However, there’s more to the movement. In that spirit…

Let’s be transparent about transparency.

When the goal of an open government project is legislative transparency through freely accessible data, let’s focus on that. When the goal is something else, let’s focus on that too. We hear about government accountability through data because the voices calling for it are loud. But data can do much more than bring about a more transparent lawmaking process.

In the words of a wise man, make transparency your Number Two.

If you haven’t had the chance to watch this aforementioned Freedom To Connect talk, and you’ve got half an hour to spare, I highly recommend it. The subject is community broadband, but it’s hard not to be inspired to frame other issues smarter, with transparency ever-present in the background.

Let’s focus on Number One.

If the THOMAS data, for example, were open right now, this instant, you couldn’t watch it on TV. You couldn’t read it on your Kindle. It’s mere presence would not increase transparency. Someone would have to do something with it. Number One is the thing you do with the data to reach your own goal–and that goal might not be legislative transparency.

As a public law librarian to a broad constituency, my goals are different than those of a non-profit think tank, or a law firm, or a law school, or even a non-law public library. In a climate of doing more with less, of needing to show much return for little investment, we each have to frame specific, measurable, achievable Number Ones tailored to the needs of our institutions. Without these Number Ones (goals, mission statements, benchmarks, or whatever management word your organization uses), we flounder off-mission, lose focus, and potentially lose funding.

Librarians are foot soldiers for the First Amendment–we like open information, we place a high value on the freedom to know. However, we’re among the first to be cut in tight budget situations, and we’re all too familiar with the perils of asking for something that’s overly broad, or asking for something that you can’t show narrowly tailored value for later on.

Librarians are foot soldiers for the First Amendment–we like open information, we place a high value on the freedom to know. However, we’re among the first to be cut in tight budget situations, and we’re all too familiar with the perils of asking for something that’s overly broad, or asking for something that you can’t show narrowly tailored value for later on.

With respect to open gov data: government accountability is not unimportant to me as a voter. However, as a law librarian, I need to focus on Number Ones with more specific, smaller-scale goals than transparency, that will create measurable outcomes, allowing me to show concrete value to my institution. The big picture of how information is available, and the relationship between the government and the governed is important, but it doesn’t always get you funding, and it can’t always answer the question of the patron in front of you.

What’s your Number One?

There’s plenty of data out there. What are you doing with it? How can you manipulate raw free resources into something good for your institution? There is much to be said for information for the sake of information. I can’t imagine needing to convince most library-types of that. That said, we library-types, we information professionals, we decision makers, and perhaps we citizens need to narrow open gov to make it work for us. Data is good, but a real-time interactive civics education program based on THOMAS data for K-12 students is better. Let transparency folks fight the good fight, and don’t forget their work. But while you’ve got your librarian hat on, focus on a Number One that works for you.

Meg Lulofs is an information professional at large, blogging at librarylulu.com, editing Pimsleur’s Checklists of Basic American Legal Publications, and making mischief. She earned a J.D. from the University of Baltimore, and a M.L.I.S. from Catholic University. She welcomes feedback at meglulofs@gmail.com. You can follow her on Twitter @librarylulu, or on Facebook at facebook.com/librarylulu.

Meg Lulofs is an information professional at large, blogging at librarylulu.com, editing Pimsleur’s Checklists of Basic American Legal Publications, and making mischief. She earned a J.D. from the University of Baltimore, and a M.L.I.S. from Catholic University. She welcomes feedback at meglulofs@gmail.com. You can follow her on Twitter @librarylulu, or on Facebook at facebook.com/librarylulu.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed. The information above should not be considered legal advice. If you require legal representation, please consult a lawyer.

[Editor’s Note] For topic-related VoxPopuLII posts please see: Nick Holmes, Accessible Law; John Sheridan, Legislation.gov.uk; David Moore, OpenGovernment.org: Researching U.S. State Legislation.