[Editor’s Note: We are republishing here, with some corrections, a post by Dr. Núria Casellas that appeared earlier on VoxPopuLII.]

[Editor’s Note: We are republishing here, with some corrections, a post by Dr. Núria Casellas that appeared earlier on VoxPopuLII.]

The organization and formalization of legal information for computer processing in order to support decision-making or enhance information search, retrieval and knowledge management is not recent, and neither is the need to represent legal knowledge in a machine-readable form. Nevertheless, since the first ideas of computerization of the law in the late 1940s, the appearance of the first legal information systems in the 1950s, and the first legal expert systems in the 1970s, claims, such as Hafner’s, that “searching a large database is an important and time-consuming part of legal work,” which drove the development of legal information systems during the 80s, have not yet been left behind.

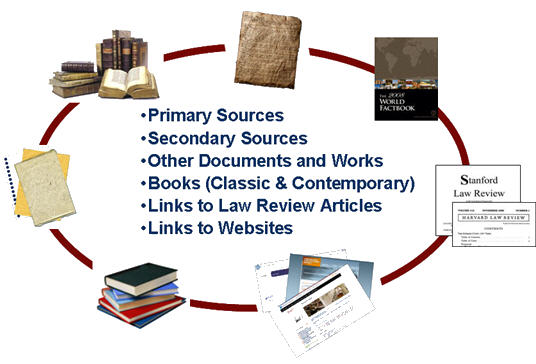

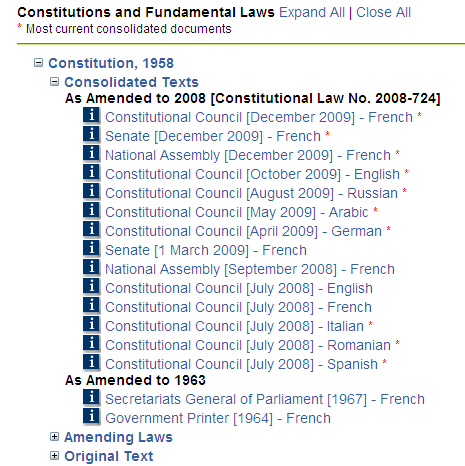

Similar claims may be found nowadays as, on the one hand, the amount of available unstructured (or poorly structured) legal information and documents made available by governments, free access initiatives, blawgs, and portals on the Web will probably keep growing as the Web expands. And, on the other, the increasing quantity of legal data managed by legal publishing companies, law firms, and government agencies, together with the high quality requirements applicable to legal information/knowledge search, discovery, and management (e.g., access and privacy issues, copyright, etc.) have renewed the need to develop and implement better content management tools and methods.

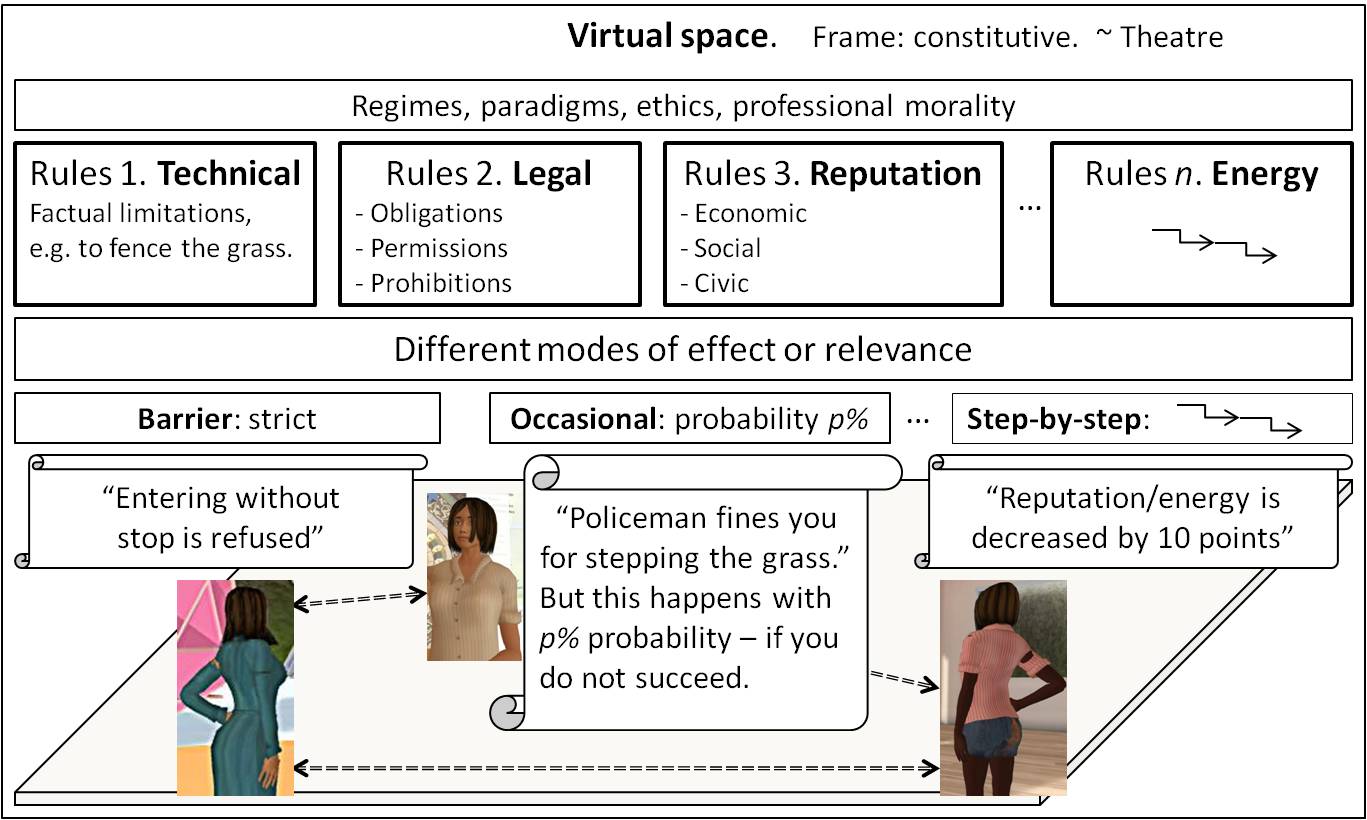

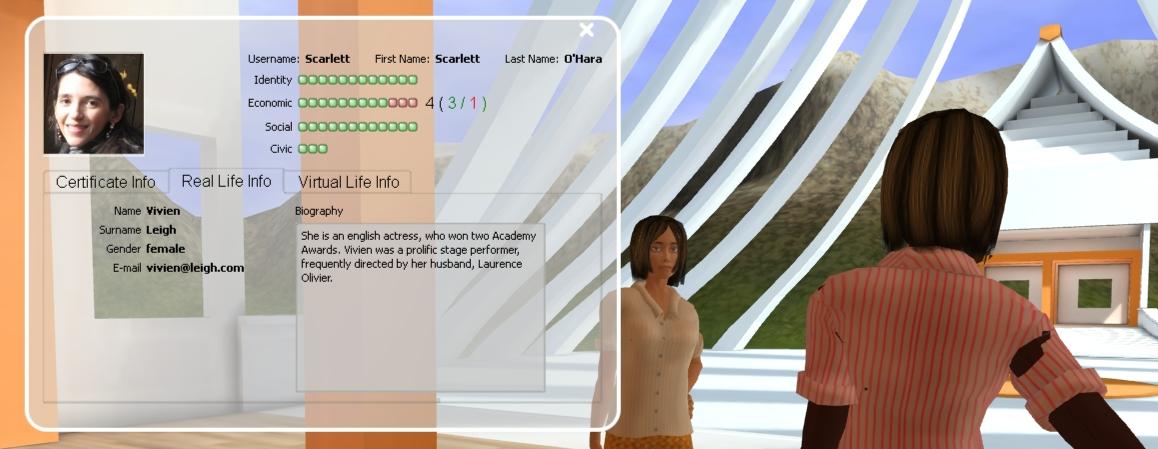

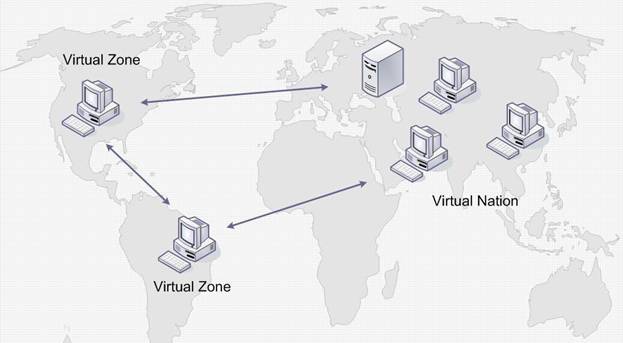

Information overload, however important, is not the only concern for the future of legal knowledge management; other and growing demands are increasing the complexity of the requirements that legal information management systems and, in consequence, legal knowledge representation must face in the future. Multilingual search and retrieval of legal information to enable, for example, integrated search between the legislation of several European countries; enhanced laypersons’ understanding of and access to e-government and e-administration sites or online dispute resolution capabilities (e.g., BATNA determination); the regulatory basis and capabilities of electronic institutions or normative and multi-agent systems (MAS); and multimedia, privacy or digital rights management systems, are just some examples of these demands.

How may we enable legal information interoperability? How may we foster legal knowledge usability and reuse between information and knowledge systems? How may we go beyond the mere linking of legal documents or the use of keywords or Boolean operators for legal information search? How may we formalize legal concepts and procedures in a machine-understandable form?

In short, how may we handle the complexity of legal knowledge to enhance legal information search and retrieval or knowledge management, taking into account the structure and dynamic character of legal knowledge, its relation with common sense concepts, the distinct theoretical perspectives, the flavor and influence of legal practice in its evolution, and jurisdictional and linguistic differences?

These are challenging tasks, for which different solutions and lines of research have been proposed. Here, I would like to draw your attention to the development of semantic solutions and applications and the construction of formal structures for representing legal concepts in order to make human-machine communication and understanding possible.

Semantic metadata

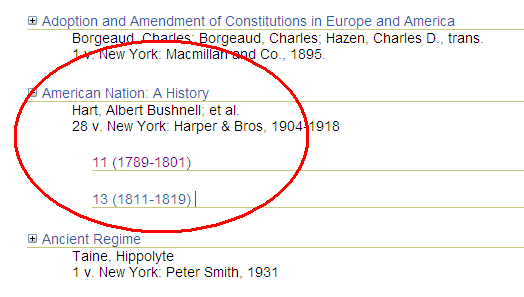

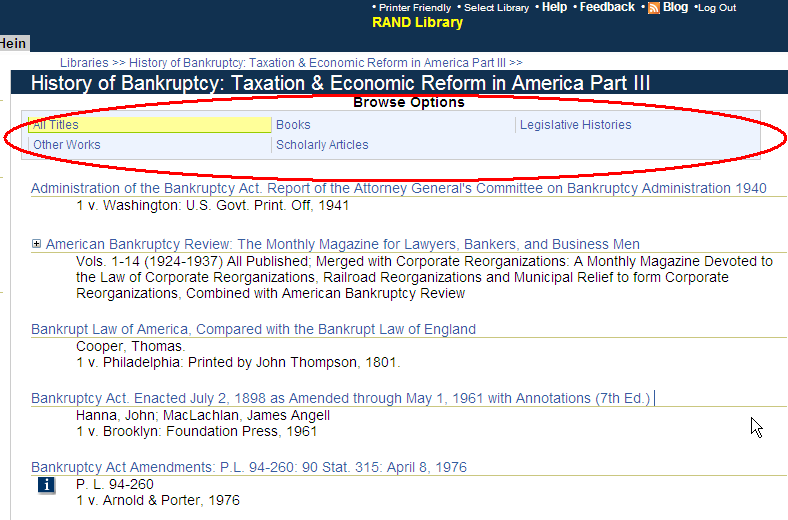

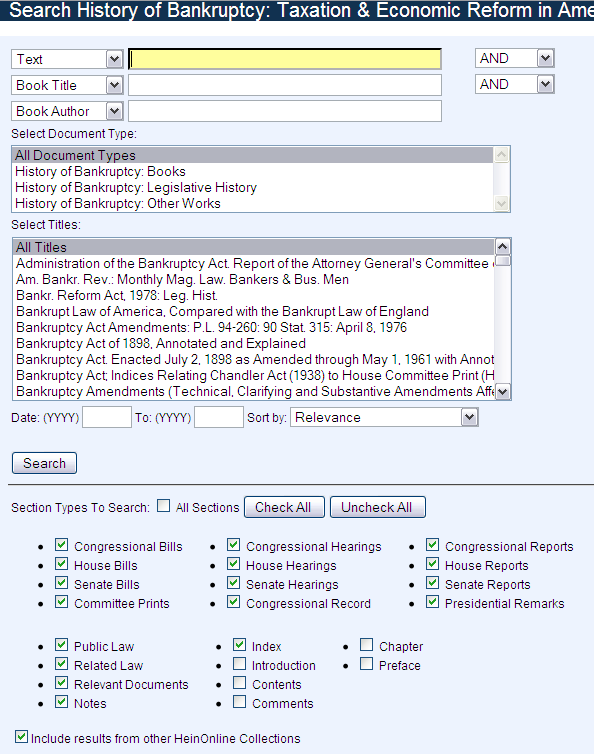

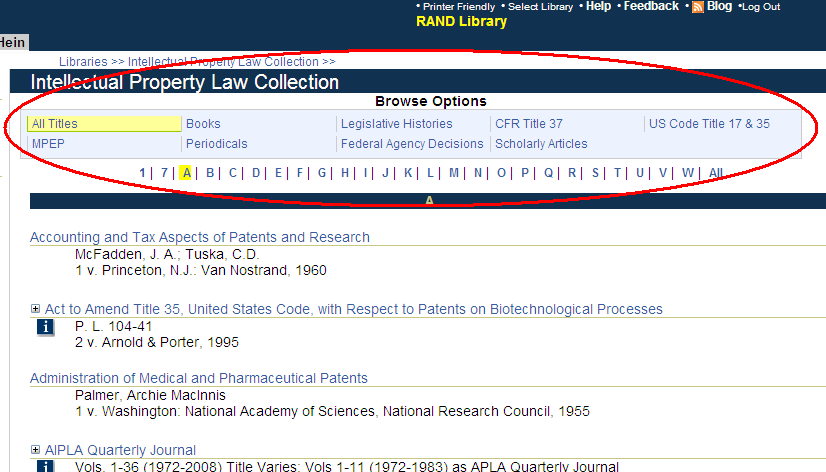

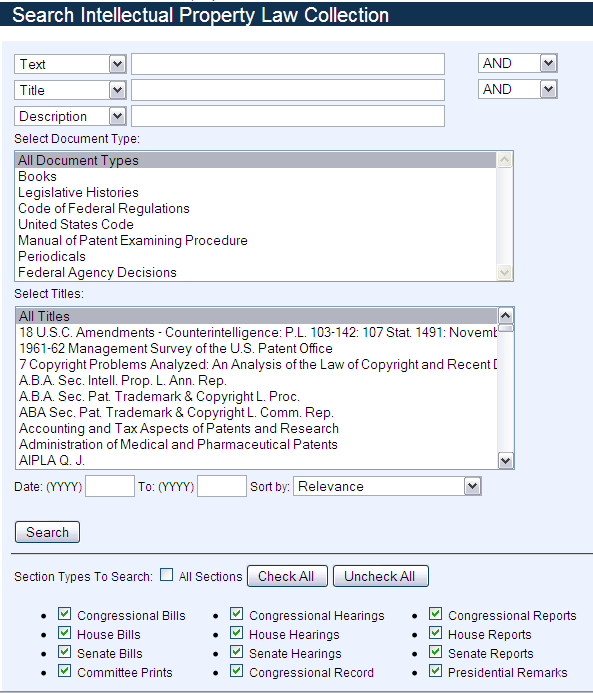

For example, in the search and retrieval area, we still perform nowadays most legal searches in online or application databases using keywords (that we believe to be contained in the document that we are searching for), maybe together with a combination of Boolean operators, or supported with a set of predefined categories (metadata regarding, for example, date, type of court, etc.), a list of pre-established topics, thesauri (e.g., EuroVoc), or a synonym-enhanced search.

These searches rely mainly on syntactic matching, and — with the exception of searches enhanced with categories, synonyms, or thesauri — they will return only documents that contain the exact term searched for. To perform more complex searches, to go beyond the term, we require the search engine to understand the semantic level of legal documents; a shared understanding of the domain of knowledge becomes necessary.

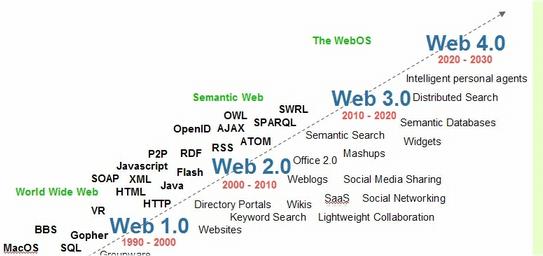

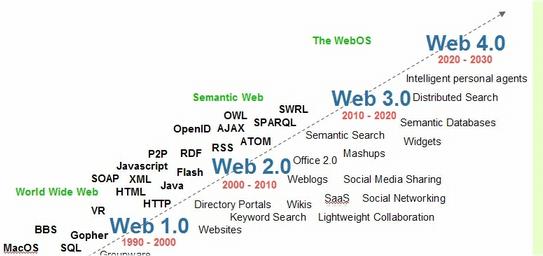

Although the quest for the representation of legal concepts is not new, these efforts have recently been driven by the success of the World Wide Web (WWW) and, especially, by the later development of the Semantic Web. Sir Tim Berners-Lee described it as an extension of the Web “in which information is given well-defined meaning, better enabling computers and people to work in cooperation.”

Thus, the Semantic Web is envisaged as an extension of the current Web, which now comprises collaborative tools and social networks (the Social Web or Web 2.0). The Semantic Web is sometimes also referred to as Web 3.0, although there is no widespread agreement on this matter, as different visions exist regarding the enhancement and evolution of the current Web.

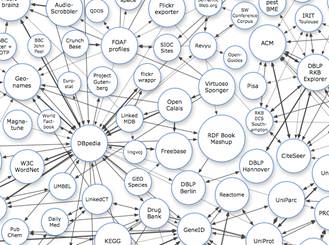

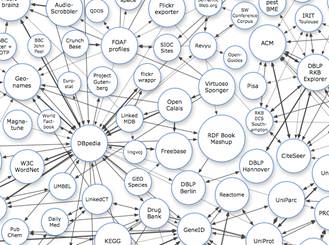

These efforts also include the Web of Data (or Linked Data), which relies on the existence of standard formats (URIs, HTTP and RDF) to allow the access and query of interrelated datasets, which may be granted through a SPARQL endpoint (e.g., Govtrack.us, US census data, etc.). Sharing and connecting data on the Web in compliance with the Linked Data principles enables the exploitation of content from different Web data sources with the development of search, browse, and other mashup applications. (See the Linking Open Data cloud diagram by Cyganiak and Jentzsch below.) [Editor’s Note: Legislation.gov.uk also applies Linked Data principles to legal information, as John Sheridan explains in his recent post.]

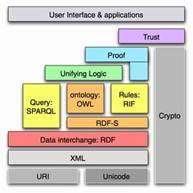

Thus, to allow semantics to be added to the current Web, new languages and tools (ontologies) were needed, as the development of the Semantic Web is based on the formal representation of meaning in order to share with computers the flexibility, intuition, and capabilities of the conceptual structures of human natural languages. In the subfield of computer science and information science known as Knowledge Representation, the term “ontology” refers to a consensual and reusable vocabulary of identified concepts and their relationships regarding some phenomena of the world, which is made explicit in a machine-readable language. Ontologies may be regarded as advanced taxonomical structures,  where concepts are formalized as classes and defined with axioms, enriched with the description of attributes or constraints, and properties.

where concepts are formalized as classes and defined with axioms, enriched with the description of attributes or constraints, and properties.

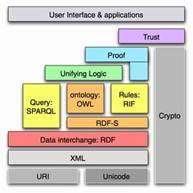

The task of developing interoperable technologies (ontology languages, guidelines, software, and tools) has been taken up by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). These technologies were arranged in the Semantic Web Stack according to increasing levels of complexity (like a layer cake). In this stack, higher layers depend on lower layers (and the latter are inherited from the original Web). These languages include XML (eXtensible Markup Language), a superset of HTML usually used to add structure to documents, and the so-called ontology languages: RDF/RDFS (Resource Description Framework/Schema), OWL, and OWL2 (Ontology Web Language). While the RDF language offers simple descriptive information about the resources on the Web, encoded in sets of triples of subject (a resource), predicate (a property or relation), and object (a resource or a value), RDFS allows the description of sets. OWL offers an even more expressive language to define structured ontologies (e.g. class disjointess, union or equivalence, etc.

Moreover, a specification to support the conversion of existing thesauri, taxonomies or subject headings into RDF triples has recently been published: the SKOS, Simple Knowledge Organization System standard. These specifications may be exploited in Linked Data efforts, such as the New York Times vocabularies. Also, EuroVoc, the multilingual thesaurus for activities of the EU is, for example, now available in this format.

Although there are different views in the literature regarding the scope of the definition or main characteristics of ontologies, the use of ontologies is seen as the key to implementing semantics for human-machine communication. Many ontologies have been built for different purposes and knowledge domains, for example:

- OpenCyc: an open source version of the Cyc general ontology;

- SUMO: the Suggested Upper Merged Ontology;

- the upper ontologies PROTON (PROTo Ontology) and DOLCE (Descriptive Ontology for Linguistic and Cognitive Engineering);

- the FRBRoo model (which represents bibliographic information);

- the RDF representation of Dublin Core;

- the Gene Ontology;

- the FOAF (Friend of a Friend) ontology.

Although most domains are of interest for ontology modeling, the legal domain offers a perfect area for conceptual modeling and knowledge representation to be used in different types of intelligent applications and legal reasoning systems, not only due to its complexity as a knowledge intensive domain, but also because of the large amount of data that it generates. The use of semantically-enabled technologies for legal knowledge management could provide legal professionals and citizens with better access to legal information; enhance the storage, search, and retrieval of legal information; make possible advanced knowledge management systems; enable human-computer interaction; and even satisfy some hopes respecting automated reasoning and argumentation.

Regarding the incorporation of legal knowledge into the Web or into IT applications, or the more complex realization of the Legal Semantic Web, several directions have been taken, such as the development of XML standards for legal documentation and drafting (including Akoma Ntoso, LexML, CEN Metalex, and Norme in Rete), and the construction of legal ontologies.

Ontologizing legal knowledge

During the last decade, research on the use of legal ontologies as a technique to represent legal knowledge has increased and, as a consequence, a very interesting debate about their capacity to represent legal concepts and their relation to the different existing legal theories has arisen. It has even been suggested that ontologies could be the “missing link” between legal theory and Artificial Intelligence.

The literature suggests that legal ontologies may be distinguished by the levels of abstraction of the ideas they represent, the key distinction being between core and domain levels. Legal core ontologies model general concepts which are believed to be central for the understanding of law and may be used in all legal domains. In the past, ontologies of this type were mainly built upon insights provided by legal theory and largely influenced by normativism and legal positivism, especially by the works of Hart and Kelsen. Thus, initial legal ontology development efforts in Europe were influenced by hopes and trends in research on legal expert systems based on syllogistic approaches to legal interpretation.

More recent contributions at that level include the LKIF-Core Ontology, the LRI-Core Ontology, the DOLCE+CLO (Core Legal Ontology), and the Ontology of Fundamental Legal Concepts. Such ontologies usually include references to the concepts of Norm, Legal Act, and Legal Person, and may contain the formalization of deontic operators (e.g., Prohibition, Obligation, and Permission).

Such ontologies usually include references to the concepts of Norm, Legal Act, and Legal Person, and may contain the formalization of deontic operators (e.g., Prohibition, Obligation, and Permission).

Domain ontologies, on the other hand, are directed towards the representation of conceptual knowledge regarding specific areas of the law or domains of practice, and are built with particular applications in mind, especially those that enable communication (shared vocabularies), or enhance indexing, search, and retrieval of legal information. Currently, most legal ontologies being developed are domain-specific ontologies, and some areas of legal knowledge have been heavily targeted, notably the representation of intellectual property rights respecting digital rights management (IPROnto Ontology, the Copyright Ontology, the Ontology of Licences, and the ALIS IP Ontology), and consumer-related legal issues (the Customer Complaint Ontology (or CContology), and the Consumer Protection Ontology). Many other well-documented ontologies have also been developed for purposes of the detection of financial fraud and other crimes; the representation of alternative dispute resolution methods, privacy compliance, patents, cases (e.g., Legal Case OWL Ontology), judicial proceedings, legal systems, and argumentation frameworks; and the multilingual retrieval of European law, among others. (See, for example, the proceedings of the JURIX and ICAIL conferences for further references.)

A socio-legal approach to legal ontology development

Thus, there are many approaches to the development of legal ontologies. Nevertheless, in the current legal ontology literature there are few explicit accounts or insights into the methods researchers use to elicit legal knowledge, and the accounts that are available reflect a lack of consensus as to the most appropriate methodology. For example, some accounts focus solely on the use of text mining techniques towards ontology learning from legal texts; while others concentrate on the analysis of legal theories and related materials to extract and formalize legal concepts. Moreover, legal ontology researchers disagree about the role that legal experts should play in ontology development and validation.

In this regard, at the Institute of Law and Technology, we are developing a socio-legal approach to the construction of legal conceptual models. This approach stems from our collaboration with firms, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations (and their experts, clients, and other users) for the gathering of either explicit or tacit knowledge according to their needs. This empirically-based methodology may require the modeling of legal knowledge in practice (or professional legal knowledge, PLK), and the acquisition of knowledge through ethnographic and other social science research methods, together with the extraction (and merging) of concepts from a range of different sources (acts, regulations, case law, protocols, technical reports, etc.) and their validation by both legal experts and users.

In this regard, at the Institute of Law and Technology, we are developing a socio-legal approach to the construction of legal conceptual models. This approach stems from our collaboration with firms, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations (and their experts, clients, and other users) for the gathering of either explicit or tacit knowledge according to their needs. This empirically-based methodology may require the modeling of legal knowledge in practice (or professional legal knowledge, PLK), and the acquisition of knowledge through ethnographic and other social science research methods, together with the extraction (and merging) of concepts from a range of different sources (acts, regulations, case law, protocols, technical reports, etc.) and their validation by both legal experts and users.

For example, the Ontology of Professional Judicial Knowledge (OPJK) was developed in collaboration with the Spanish School of the Judicary to enhance search and retrieval capabilities of a Web-based frequentl- asked-question system (IURISERVICE) containing a repository of practical knowledge for Spanish judges in their first appointment. The knowledge was elicited from an ethnographic survey in Spanish First Instance Courts. On the other hand, the Neurona Ontologies, for a data protection compliance application, are based on the knowledge of legal experts and the requirements of enterprise asset management, together with the analysis of privacy and data protection regulations and technical risk management standards.

This approach tries to take into account many of the criticisms that developers of legal knowledge-based systems (LKBS) received during the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, including, primarily, the lack of legal knowledge or legal domain understanding of most LKBS development teams at the time. These criticisms were rooted in the widespread use of legal sources (statutes, case law, etc.) directly as the knowledge for the knowledge base, instead of including in the knowledge base the “expert” knowledge of lawyers or law-related professionals.

Further, in order to represent knowledge in practice (PLK), legal ontology engineering could benefit from the use of social science research methods for knowledge elicitation, institutional/organizational analysis (institutional ethnography), as well as close collaboration with legal practitioners, users, experts, and other stakeholders, in order to discover the relevant conceptual models that ought to be represented in the ontologies. Moreover, I understand the participation of these stakeholders in ontology evaluation and validation to be crucial to ensuring consensus about, and the usability of, a given legal ontology.

Challenges and drawbacks

Although the use of ontologies and the implementation of the Semantic Web vision may offer great advantages to information and knowledge management, there are great challenges and problems to be overcome.

First, the problems related to knowledge acquisition techniques and bottlenecks in software engineering are inherent in ontology engineering, and ontology development is quite a time-consuming and complex task. Second, as ontologies are directed mainly towards enabling some communication on the basis of shared conceptualizations, how are we to determine the sharedness of a concept? And how are context-dependencies or (cultural) diversities to be represented? Furthermore, how can we evaluate the content of ontologies?

Current research is focused on overcoming these problems through the establishment of gold standards in concept extraction and ontology learning from texts, and the idea of collaborative development of legal ontologies, although these techniques might be unsuitable for the development of certain types of ontologies. Also, evaluation (validation, verification, and assessment) and quality measurement of ontologies are currently an important topic of research, especially ontology assessment and comparison for reuse purposes.

Current research is focused on overcoming these problems through the establishment of gold standards in concept extraction and ontology learning from texts, and the idea of collaborative development of legal ontologies, although these techniques might be unsuitable for the development of certain types of ontologies. Also, evaluation (validation, verification, and assessment) and quality measurement of ontologies are currently an important topic of research, especially ontology assessment and comparison for reuse purposes.

Regarding ontology reuse, the general belief is that the more abstract (or core) an ontology is, the less it owes to any particular domain and, therefore, the more reusable it becomes across domains and applications. This generates a usability-reusability trade-off that is often difficult to resolve.

Finally, once created, how are these ontologies to evolve? How are ontologies to be maintained and new concepts added to them?

Over and above these issues, in the legal domain there are taking place more particularized discussions: for example, the discussion of the advantages and drawbacks of adopting an empirically based perspective (bottom-up), and the complexity of establishing clear connections with legal dogmatics or general legal theory approaches (top-down). To what extent are these two different perspectives on legal ontology development incompatible? How might they complement each other? What is their relationship with text-based approaches to legal ontology modeling?

I would suggest that empirically based, socio-legal methods of ontology construction constitute a bottom-up approach that enhances the usability of ontologies, while the general legal theory-based approach to ontology engineering fosters the reusability of ontologies across multiple domains.

The scholarly discussion of legal ontology development also embraces more fundamental issues, among them the capabilities of ontology languages for the representation of legal concepts, the possibilities of incorporating a legal flavor into OWL, and the implications of combining ontology languages with the formalization of rules.

Finally, the potential value to legal ontology of other approaches, areas of expertise, and domains of knowledge construction ought to be explored, for example: pragmatics and sociology of law methodologies, experiences in biomedical ontology engineering, formal ontology approaches,  and the relationships between legal ontology and legal epistemology, legal knowledge and common sense or world knowledge, expert and layperson’s knowledge, legal information and Linked Data possibilities, and legal dogmatics and political science (e.g., in e-Government ontologies).

and the relationships between legal ontology and legal epistemology, legal knowledge and common sense or world knowledge, expert and layperson’s knowledge, legal information and Linked Data possibilities, and legal dogmatics and political science (e.g., in e-Government ontologies).

As you may see, the challenges faced by legal ontology engineering are great, and the limitations of legal ontologies are substantial. Nevertheless, the potential of legal ontologies is immense. I believe that law-related professionals and legal experts have a central role to play in the successful development of legal ontologies and legal semantic applications.

[Editor’s Note: For many of us, the technical aspects of ontologies and the Semantic Web are unfamiliar. Yet these technologies are increasingly being incorporated into the legal information systems that we use everyday, so it’s in our interest to learn more about them. For those of us who would like a user-friendly introduction to ontologies and the Semantic Web, here are some suggestions:

- Tom Gruber, Where the Social Web Meets the Semantic Web (video);

- Sandro Hawke, How the Semantic Web Works;

- Kevin Hemenway, The Semantic Web: 1-2-3;

- Jim Hendler et al., Introduction to the Semantic Web (video);

- Ivan Herman, Introduction to the Semantic Web;

- Brian Lowe, Introduction to Ontologies: Adding Meaning to Metadata;

- Marek Obitko, Introduction to Ontologies and Semantic Web;

- Sean B. Palmer, The Semantic Web: An Introduction;

- Ioana Robu et al., An Introduction to the Semantic Web for Health Sciences Librarians;

- Barry Smith, Ontology: An Introduction: Video: How to Build an Ontology;

- University of Manchester, CO-ODE, Tutorial: A Practical Introduction to Ontologies and OWL;

- Dr. Adam Z. Wyner, Legal Ontologies Spin a Semantic Web.]

Dr. Núria Casellas is a visiting researcher at the Legal Information Institute at Cornell University. She is a researcher at the Institute of Law and Technology and an assistant professor at the UAB Law School (on leave). She has participated in several national and European-funded research projects regarding legal ontologies and legal knowledge management: these concern the acquisition of knowledge in judicial settings (IURISERVICE), modeling privacy compliance regulations (NEURONA), drafting legislation (DALOS), and the Legal Case Study of the Semantically Enabled Knowledge Technologies (SEKT VI Framework project), among others. Co-editor of the IDT Series, she holds a Law Degree from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, a Master’s Degree in Health Care Ethics and Law from the University of Manchester, and a PhD (“Modelling Legal Knowledge through Ontologies. OPJK: the Ontology of Professional Judicial Knowledge”).

Dr. Núria Casellas is a visiting researcher at the Legal Information Institute at Cornell University. She is a researcher at the Institute of Law and Technology and an assistant professor at the UAB Law School (on leave). She has participated in several national and European-funded research projects regarding legal ontologies and legal knowledge management: these concern the acquisition of knowledge in judicial settings (IURISERVICE), modeling privacy compliance regulations (NEURONA), drafting legislation (DALOS), and the Legal Case Study of the Semantically Enabled Knowledge Technologies (SEKT VI Framework project), among others. Co-editor of the IDT Series, she holds a Law Degree from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, a Master’s Degree in Health Care Ethics and Law from the University of Manchester, and a PhD (“Modelling Legal Knowledge through Ontologies. OPJK: the Ontology of Professional Judicial Knowledge”).

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editor in Chief is Robert Richards.

Is this perception true? Presently, we have no way of systematically answering this and related questions. Why? Because scholars do not possess the population of international treaties and, without this population, it is not possible to draw a truly representative sample on which to study. This theme is echoed in the recent working paper by Miles & Posner (2008) where the authors note: “[M]any empirical regularities of treaty-making remain almost entirely unknown. Basic facts, such as which types of treaties countries most commonly enter and which types of countries engage in the most treaty-making –- let alone what are the consequences of treatymaking –- have not been established.”

Is this perception true? Presently, we have no way of systematically answering this and related questions. Why? Because scholars do not possess the population of international treaties and, without this population, it is not possible to draw a truly representative sample on which to study. This theme is echoed in the recent working paper by Miles & Posner (2008) where the authors note: “[M]any empirical regularities of treaty-making remain almost entirely unknown. Basic facts, such as which types of treaties countries most commonly enter and which types of countries engage in the most treaty-making –- let alone what are the consequences of treatymaking –- have not been established.” Though these projects have coded the makeup of various treaties, they are of limited scope. They either focus on a specific treaty topic, contain a random (or not so random) sub-sample of specific treaty categories, or limit their compilation to just multilateral agreements. Truly gaining a perspective on the development and dynamics of global cooperation via treaty making requires a broader and more comprehensive treaty compilation. The World Treaty Index, as first developed by Rohn (1983), avoids these limitations.

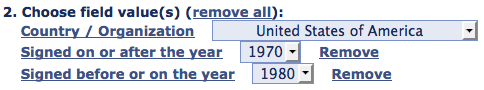

Though these projects have coded the makeup of various treaties, they are of limited scope. They either focus on a specific treaty topic, contain a random (or not so random) sub-sample of specific treaty categories, or limit their compilation to just multilateral agreements. Truly gaining a perspective on the development and dynamics of global cooperation via treaty making requires a broader and more comprehensive treaty compilation. The World Treaty Index, as first developed by Rohn (1983), avoids these limitations. The next two fields record the parties of the treaty if the treaty is bilateral or unilateral. We are working on incorporating multilateral agreements into a single query. In our current database schema, we separate these queries from queries for bilateral treaties by allowing for bulk download of metadata for all multilateral agreements. (Click here for the page offering bulk access to metadata for multilateral agreements.) Following the results presented in Poast (2010), we would encourage scholars to carefully consider how best to combine datasets of metadata for multilateral and bilateral treaties.

The next two fields record the parties of the treaty if the treaty is bilateral or unilateral. We are working on incorporating multilateral agreements into a single query. In our current database schema, we separate these queries from queries for bilateral treaties by allowing for bulk download of metadata for all multilateral agreements. (Click here for the page offering bulk access to metadata for multilateral agreements.) Following the results presented in Poast (2010), we would encourage scholars to carefully consider how best to combine datasets of metadata for multilateral and bilateral treaties. Paul Poast is currently a Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan. In the Fall 2011, he will be an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Rutgers University.

Paul Poast is currently a Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan. In the Fall 2011, he will be an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Rutgers University. Daniel Martin Katz is currently a Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science and Public Policy at the University of Michigan. He is also a Fellow in Empirical Legal Studies at the University of Michigan Law School. In the Fall 2011, he will be an Assistant Professor of Law at the Michigan State University College of Law.

Daniel Martin Katz is currently a Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science and Public Policy at the University of Michigan. He is also a Fellow in Empirical Legal Studies at the University of Michigan Law School. In the Fall 2011, he will be an Assistant Professor of Law at the Michigan State University College of Law. Michael J. Bommarito II is currently a Ph.D. Pre-Candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan. He also has a Masters in Financial Engineering from the University of Michigan.

Michael J. Bommarito II is currently a Ph.D. Pre-Candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan. He also has a Masters in Financial Engineering from the University of Michigan.

Vytautas Čyras

Vytautas Čyras

Such ontologies usually include references to the concepts of Norm, Legal Act, and Legal Person, and may contain the formalization of

Such ontologies usually include references to the concepts of Norm, Legal Act, and Legal Person, and may contain the formalization of  In this regard, at

In this regard, at  Current research is focused on overcoming these problems through the establishment of gold standards in concept extraction and ontology learning from texts, and the idea of

Current research is focused on overcoming these problems through the establishment of gold standards in concept extraction and ontology learning from texts, and the idea of  and the relationships between legal ontology and legal epistemology, legal knowledge and common sense or world knowledge, expert and layperson’s knowledge, legal information and Linked Data possibilities, and legal dogmatics and political science (e.g., in

and the relationships between legal ontology and legal epistemology, legal knowledge and common sense or world knowledge, expert and layperson’s knowledge, legal information and Linked Data possibilities, and legal dogmatics and political science (e.g., in

As I said, the lorises move slowly. Glacially, even. I mean, I’m talking sloooooooow. Why is that? Well, they don’t have a physical impediment keeping them that way. Nor should it be assumed that they are lazy or have some other character defect (as if one could assign character defects to wild animals.) As a matter of fact, when they choose to catch live prey they can move quite quickly. They operate this way because when one is creeping along small jungle branches high in the air in the middle of the night and not running from any particular predator, it pays off to take one’s time and be cautious.

As I said, the lorises move slowly. Glacially, even. I mean, I’m talking sloooooooow. Why is that? Well, they don’t have a physical impediment keeping them that way. Nor should it be assumed that they are lazy or have some other character defect (as if one could assign character defects to wild animals.) As a matter of fact, when they choose to catch live prey they can move quite quickly. They operate this way because when one is creeping along small jungle branches high in the air in the middle of the night and not running from any particular predator, it pays off to take one’s time and be cautious. So instead I say, “Get in the goddamn wagon or get out of the goddamn way.” I imagine at times the ride will be about as comfortable and collegial as a bunch of children crammed in a station wagon for a family vacation road trip. There is no ultimate “Mother” authority to keep us all in line with the threat of turning around, however. For these collaborative efforts to be successful, no constituency or person gets to be “in charge” all the time. It doesn’t matter how many millions of dollars in grant money one has, or how many thousands of members in one’s organization; everyone’s expertise needs to be used and respected. It won’t be easy and it won’t feel natural, but we all must make a conscious effort to work together.

So instead I say, “Get in the goddamn wagon or get out of the goddamn way.” I imagine at times the ride will be about as comfortable and collegial as a bunch of children crammed in a station wagon for a family vacation road trip. There is no ultimate “Mother” authority to keep us all in line with the threat of turning around, however. For these collaborative efforts to be successful, no constituency or person gets to be “in charge” all the time. It doesn’t matter how many millions of dollars in grant money one has, or how many thousands of members in one’s organization; everyone’s expertise needs to be used and respected. It won’t be easy and it won’t feel natural, but we all must make a conscious effort to work together.