Artisanal Algorithms

Down here in Durham, NC, we have artisanal everything: bread, cheese, pizza, peanut butter, and of course coffee, coffee, and more coffee. It’s great—fantastic food and coffee, that is, and there is no doubt some psychological kick from knowing that it’s been made carefully by skilled craftspeople for my enjoyment. The old ways are better, at least until they’re co-opted by major multinational corporations.

Aside from making you either hungry or jealous, or perhaps both, why am I talking about fancy foodstuffs on a blog about legal information? It’s because I’d like to argue that algorithms are not computerized, unknowable, mysterious things—they are produced by people, often painstakingly, with a great deal of care. Food metaphors abound, helpfully I think. Algorithms are the “special sauce” of many online research services. They are sets of instructions to be followed and completed, leading to a final product, just like a recipe. Above all, they are the stuff of life for the research systems of the near future.

Human Mediation Never Went Away

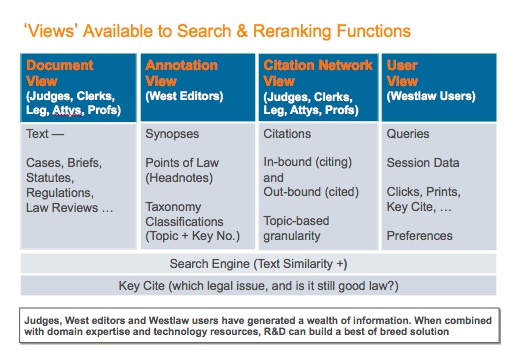

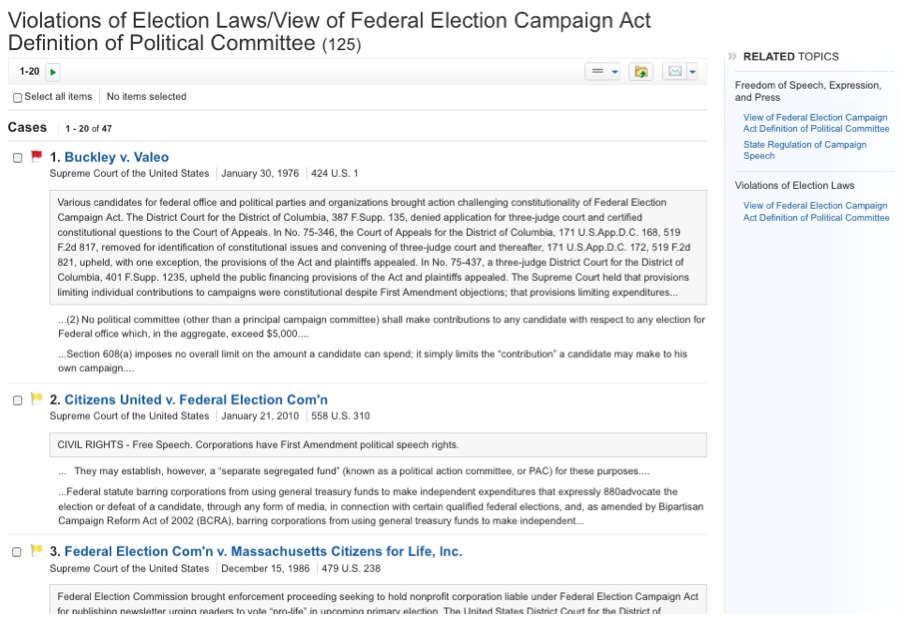

When we talk about algorithms in the research community, we are generally talking about search or information retrieval (IR) algorithms. A recent and fascinating VoxPopuLII post by Qiang Lu and Jack Conrad, “Next Generation Legal Search – It’s Already Here,” discusses how these algorithms have become more complicated by considering factors beyond document-based, topical relevance. But I’d like to step back for a moment and head into the past for a bit to talk about the beginnings of search, and the framework that we have viewed it within for the past half-century.

Many early information-retrieval systems worked like this: a researcher would come to you, the information professional, with an information need, that vague and negotiable idea which you would try to reduce to a single question or set of questions. With your understanding of Boolean search techniques and your knowledge of how the document corpus you were searching was indexed, you would then craft a search for the computer to run. Several hours later, when the search was finished, you would be presented with a list of results, sometimes ranked in order of relevance and limited in size because of a lack of computing power. Presumably you would then share these results with the researcher, or perhaps just turn over the relevant documents and send him on his way. In the academic literature, this was called “delegated search,” and it formed the background for the most influential information retrieval studies and research projects for many years—the Cranfield Experiments. See also “On the History of Evaluation in IR” by Stephen Robertson (2008).

In this system, literally everything—the document corpus, the index, the query, and the results—were mediated. There was a medium, a middle-man. The dream was to some day dis-intermediate, which does not mean to exhume the body of the dead news industry. (I feel entitled to this terrible joke as a former journalist… please forgive me.) When the World Wide Web and its ever-expanding document corpus came on the scene, many thought that search engines—huge algorithms, basically—would remove any barrier between the searcher and the information she sought. This is “end-user” search, and as algorithms improved, so too would the system, without requiring the searcher to possess any special skills. The searcher would plug a query, any query, into the search box, and the algorithm would present a ranked list of results, high on both recall and precision. Now, the lack of human attention, evidenced by the fact that few people ever look below result 3 on the list, became the limiting factor, instead of the lack of computing power.

The only problem with this is that search engines did not remove the middle-man—they became the middle-man. Why? Because everything, whether we like it or not, is editorial, especially in reference or information retrieval. Everything, every decision, every step in the algorithm, everything everywhere, involves choice. Search engines, then, are never neutral. They embody the priorities of the people who created them and, as search logs are analyzed and incorporated, of the people who use them. It is in these senses that algorithms are inherently human.

Empowering the Searcher by Failing Consistently

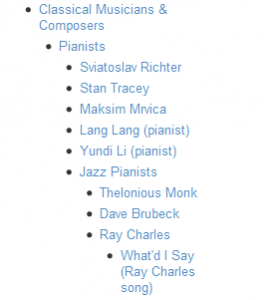

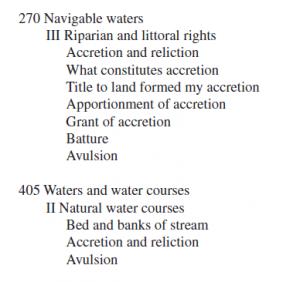

In the context of legal research, then, it makes sense to consider algorithms as secondary sources. Law librarians and legal research instructors can explain the advantages of controlled vocabularies like the Topic and Key Number System®, of annotated statutes, and of citators. In several legal research textbooks, full-text keyword searching is anathema because, I suppose, no one knows what happens directly after you type the words into the box and click search. It seems frightening. We are leaping without looking, trusting our searches to some kind of computer voodoo magic.

This makes sense—search algorithms are often highly guarded secrets, even if what they select for (timeliness, popularity, and dwell time, to name a few) is made known. They are opaque. They apparently do not behave reliably, at least in some cases. But can’t the same be said for non-algorithmic information tools, too? Do we really know which types of factors figure in to the highly vaunted editorial judgment of professionals?

To take the examples listed above—yes, we know what the Topics and Key Numbers are, but do we really know them well enough to explain why the work the way they do, what biases are baked-in from over a century of growth and change? Without greater transparency, I can’t tell you.

How about annotated statutes: who knows how many of the cases cited on online platforms are holdovers from the soon-to-be print publications of yesteryear? In selecting those cases, surely the editors had to choose to omit some, or perhaps many, because of space constraints. How, then, did the editors determine which cases were most on-point in interpreting a given statutory section, that is, which were most relevant? What algorithms are being used today to rank the list of annotations? Again, without greater transparency, I can’t tell you.

And when it comes to citators, why is there so much discrepancy between a case’s classification and which later-citing cases are presented as evidence of this classification? There have been several recent studies, like this one and this one, looking into the issue, but more research is certainly needed.

Finally, research in many fields is telling us that human judgments of relevance are highly subjective in the first place. At least one court has said that algorithmic predictive coding is better at finding relevant documents during pretrial e-discovery than humans are.

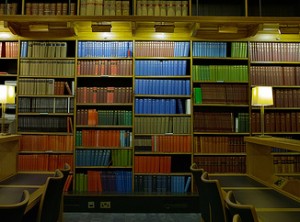

Where are the relevant documents? Source: CC BY 2.0, flickr user gosheshe

I am not presenting these examples to discredit subjectivity in the creation of information tools. What I am saying is that the dichotomy between editorial and algorithmic, between human and machine, is largely a false one. Both are subjective. But why is this important?

Search algorithms, when they are made transparent to researchers, librarians, and software developers (i.e. they are “open source”), do have at least one distinct advantage over other forms of secondary sources—when they fail, they fail consistently. After the fact or even in close to real-time, it’s possible to re-program the algorithm when it is not behaving as expected.

Another advantage to thinking of algorithms as just another secondary source is that, demystified, they can become a less privileged (or, depending on your point of view, less demonized) part of the research process. The assumption that the magic box will do all of the work for you is just as dangerous as the assumption that the magic box will do nothing for you. Teaching about search algorithms allows for an understanding of them, especially if the search algorithms are clear about which editorial judgments have been prioritized.

Beyond Search, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Automated Research Tools

As an employee at Fastcase, Inc. this past summer, I had the opportunity to work on several innovative uses of algorithms in legal research, most notably on the new automated citation-analysis tool Bad Law Bot. Bad Law Bot, at least in its current iteration, works by searching the case law corpus for significant signals—words, phrases, or citations to legal documents—and, based on criteria selected in advance, determines whether a case has been given negative treatment in subsequent cases. The tool is certainly automated, but the algorithm is artisanal—it was massaged and kneaded by caring craftsmen to deliver a premium product. The results it delivered were also tested meticulously to find out where the algorithm had failed. And then the process started over again.

This is just one example of what I think the future of much general legal research will look like—smart algorithms built and tested by people, taking advantage of near unlimited storage space and ever-increasing computing power to process huge datasets extremely fast. Secondary sources, at least the ones organizing, classifying, and grouping primary law, will no longer be static things. Rather, they will change quickly when new documents are available or new uses for those documents are dreamed up. It will take hard work and a realistic set of expectations to do it well.

Computer assisted legal research cannot be about merely returning ranked lists of relevant results, even as today’s algorithms get better and better at producing these lists. Search must be only one component of a holistic research experience in which the searcher consults many tools which, used together, are greater than the sum of their parts. Many of those tools will be built by information professionals and software engineers using algorithms, and will be capable of being updated and changed as the corpus and user need changes.

It’s time that we stop thinking of algorithms as alien, or other, or too complicated, or scary. Instead, we should think of them as familiar and human, as sets of instructions hand-crafted to help us solve problems with research tools that we have not yet been able to solve, or that we did not know were problems in the first place.

Aaron Kirschenfeld is currently pursuing a dual J.D. / M.S.I.S. at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His main research interests are legal research instruction, the philosophy and aesthetics of legal citation analysis, and privacy law. You can reach him on Twitter @kirschsubjudice.

Aaron Kirschenfeld is currently pursuing a dual J.D. / M.S.I.S. at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His main research interests are legal research instruction, the philosophy and aesthetics of legal citation analysis, and privacy law. You can reach him on Twitter @kirschsubjudice.

His views do not represent those of his part-time employer, Fastcase, Inc. Also, he has never hand-crafted an algorithm, let alone a wheel of cheese, but appreciates the work of those who do immensely.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed.