At CourtListener, we are making a free database of court opinions with the ultimate goal of providing the entire U.S. case-law corpus to the world for free and combining it with cutting-edge search and research tools. We–like most readers of this blog–believe that for justice to truly prevail, the law must be open and equally accessible to everybody.

At CourtListener, we are making a free database of court opinions with the ultimate goal of providing the entire U.S. case-law corpus to the world for free and combining it with cutting-edge search and research tools. We–like most readers of this blog–believe that for justice to truly prevail, the law must be open and equally accessible to everybody.

It is astonishing to think that the entire U.S. case-law corpus is not currently available to the world at no cost. Many have started down this path and stopped, so we know we’ve set a high goal for a humble open source project. From time to time it’s worth taking a moment to reflect on where we are and where we’d like to go in the coming years.

The current state of affairs

We’ve created a good search engine that can provide results based on a number of characteristics of legal cases. Our users can search for opinions by the case name, date, or any text that’s in the opinion, and can refine by court, by precedential status or by citation. The results are pretty good, but are limited based on the data we have and the “relevance signals” that we have in place.

A good legal search engine will use a number of factors (a.k.a. “relevance signals”) to promote documents to the top of their listings. Things like:

- How recent is the opinion?

- How many other opinions have cited it?

- How many journals have cited it?

- How long is it?

- How important is the court that heard the case?

- Is the case in the jurisdiction of the user?

- Is the opinion one that the user has looked at before?

- What was the subsequent treatment of the opinion?

And so forth. All of the above help to make search results better, and we’ve seen paid legal search tools make great strides in their products by integrating these and other factors. At CourtListener, we’re using a number of the above, but we need to go further. We need to use as many factors as possible, we need to learn how the factors interact with each other, which ones are the most important, and which lead to the best results.

A different problem we’re working to solve at CourtListener is getting primary legal materials freely onto the Web. What good is a search engine if the opinion you need isn’t there in the first place? We currently have about 800,000 federal opinions, including West’s second and third Federal Reporters, F.2d and F.3d, and the entire Supreme Court corpus. This is good and we’re very proud of the quality of our database–we think it’s the best free resource there is. Every day we add the opinions from the Circuit Courts in the federal system and the U.S. Supreme Court, nearly in real-time. But we need to go further: we need to add state opinions, and we need to add not just the latest opinions but all the historical ones as well.

This sounds daunting, but it’s a problem that we hope will be solved in the next few years. Although it’s taking longer than we would like, in time we are confident that all of the important historical legal data will make its way to the open Internet. Primary legal sources are already in the public domain, so now it’s just a matter of getting it into good electronic formats so that anyone can access it and anyone can re-use it. If an opinion only exists as unsearchable scanned versions, in bound books, or behind a pricey pay wall, then it’s closed to many people that should have access to it. As part of our citation identification project, which I’ll talk about next, we’re working to get the most important documents properly digitized.

Our citation identification project was developed last year by U.C. Berkeley School of Information students Rowyn McDonald and Karen Rustad to identify and cross-link any citations found in our database. This is a great feature that makes all the citations in our corpus link to the correct opinions, if we have them. For example, if you’re reading an opinion that has a reference to Roe v. Wade, you can click on the citation, and you’ll be off and reading Roe v. Wade. By the way, if you’re wondering how many Federal Appeals opinions cite Roe v. Wade, the number in our system is 801 opinions (and counting). If you’re wondering what the most-cited opinion in our system is, you may be bemused: With about 10,000 citations, it’s an opinion about ineffective assistance of legal counsel in death penalty cases, Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984).

A feature we’ll be working on soon will tie into our citation system to help us close any gaps in our corpus. Once the feature is done, whenever an opinion is cited that we don’t yet have, our users will be able to pay a small amount–one or two dollars–to sponsor the digitization of that opinion. We’ll do the work of digitizing it, and after that point the opinion will be available to the public for free.

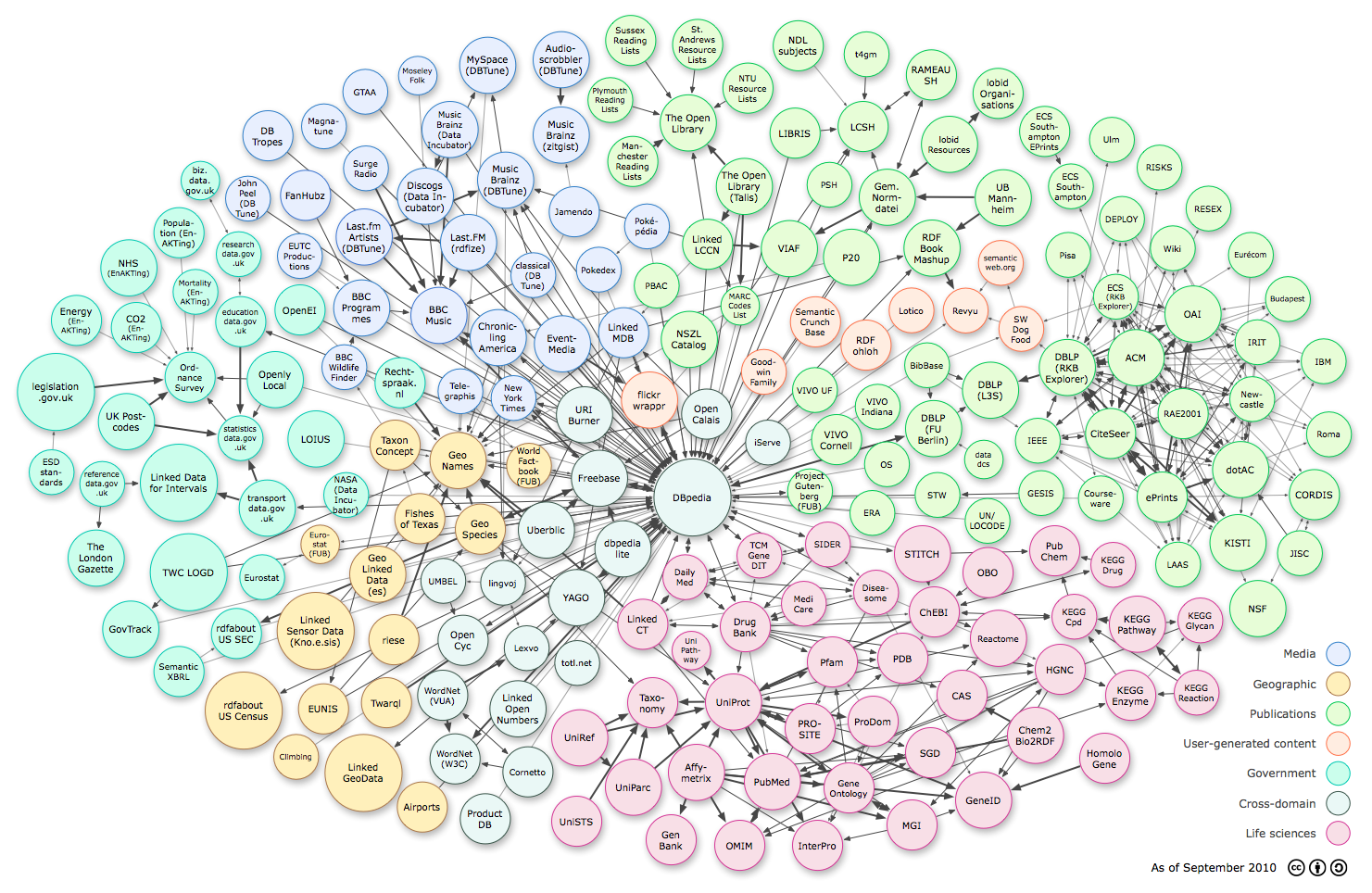

This brings us to the next big feature we added last year: bulk data. Because we want to assist academic  researchers and others who might have a use for a large database of court opinions, we provide free bulk downloads of everything we have. Like Carl Malamud’s Resource.org, (to whom we owe a great debt for his efforts to collect opinions and provide them to others for free and for his direct support of our efforts) we have giant files you can download that provide thousands of opinions in computer-readable format. These downloads are available by court and date, and include thousands of fixes to the Resource.org corpus. They also include something you can’t find anywhere else: the citation network. As part of the metadata associated with each opinion in our bulk download files, you can look and see which opinions it cites as well as which opinions cite it. This provides a valuable new source of data that we are very eager for others to work with. Of course, as new opinions are added to our system, we update our downloads with the new citations and the new information.

researchers and others who might have a use for a large database of court opinions, we provide free bulk downloads of everything we have. Like Carl Malamud’s Resource.org, (to whom we owe a great debt for his efforts to collect opinions and provide them to others for free and for his direct support of our efforts) we have giant files you can download that provide thousands of opinions in computer-readable format. These downloads are available by court and date, and include thousands of fixes to the Resource.org corpus. They also include something you can’t find anywhere else: the citation network. As part of the metadata associated with each opinion in our bulk download files, you can look and see which opinions it cites as well as which opinions cite it. This provides a valuable new source of data that we are very eager for others to work with. Of course, as new opinions are added to our system, we update our downloads with the new citations and the new information.

Finally, we would be remiss if we didn’t mention our hallmark feature: daily, weekly and monthly email alerts. For any query you put into CourtListener, you can request that we email you whenever there are new results. This feature was the first one we created, and one that we continue to be excited about. This year we haven’t made any big innovations to our email alerts system, but its popularity has continued to grow, with more than 500 alerts run each day. Next year, we hope to add a couple small enhancements to this feature so it’s smoother and easier to use.

The future

I’ve hinted at a lot of our upcoming work in the sections above, but what are the big-picture features that we think we need to achieve our goals?

We do all of our planning in the open, but we have a few things cooking in the background that we hope to eventually build. Among them are ideas for adding oral argument audio, case briefs, and data from PACER. Adding these new types of information to CourtListener is a must if we want to be more useful for research purposes, but doing so is a long-term goal, given the complexity of doing them well.

We also plan to build an opinion classifier that could automatically, and without human intervention, determine the subsequent treatment of opinions. Done right, this would allow our users to know at a glance if the opinion they’re reading was subsequently followed, criticized, or overruled, making our system even more valuable to our users.

In the next few years, we’ll continue building out these features, but as an open-source and open-data project, everything we do is in the open. You can see our plans on our feature tracker, our bugs in our bug tracker, and can get in touch in our forum. The next few years look to be very exciting as we continue building our collection and our platform for legal research. Let’s see what the new year brings!

Michael Lissner is the co-founder and lead developer of CourtListener, a project that works to make the law more accessible to all. He graduated from U.C. Berkeley’s School of Information, and when he’s not working on CourtListener he develops search and eDiscovery solutions for law firms. Michael is passionate about bringing greater access to our primary legal materials, about how technology can replace old legal models, and about open source, community-driven approaches to legal research.

Michael Lissner is the co-founder and lead developer of CourtListener, a project that works to make the law more accessible to all. He graduated from U.C. Berkeley’s School of Information, and when he’s not working on CourtListener he develops search and eDiscovery solutions for law firms. Michael is passionate about bringing greater access to our primary legal materials, about how technology can replace old legal models, and about open source, community-driven approaches to legal research.

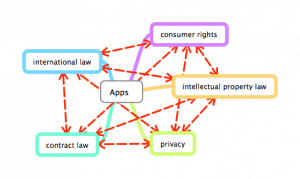

Brian W. Carver is Assistant Professor at the U.C. Berkeley School of Information where he does ressearch on and teaches about intellectual property law and cyberlaw. He is also passionate about the public’s access to the law. In 2009 and 2010 he advised an I School Masters student, Michael Lissner, on the creation of CourtListener.com, an alert service covering the U.S. federal appellate courts. After Michael’s graduation, he and Brian continued working on the site and have grown the database of opinions to include over 750,000 documents. In 2011 and 2012, Brian advised I School Masters students Rowyn McDonald and Karen Rustad on the creation of a legal citator built on the CourtListener database.

Brian W. Carver is Assistant Professor at the U.C. Berkeley School of Information where he does ressearch on and teaches about intellectual property law and cyberlaw. He is also passionate about the public’s access to the law. In 2009 and 2010 he advised an I School Masters student, Michael Lissner, on the creation of CourtListener.com, an alert service covering the U.S. federal appellate courts. After Michael’s graduation, he and Brian continued working on the site and have grown the database of opinions to include over 750,000 documents. In 2011 and 2012, Brian advised I School Masters students Rowyn McDonald and Karen Rustad on the creation of a legal citator built on the CourtListener database.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt. Editors-in-Chief are Stephanie Davidson and Christine Kirchberger, to whom queries should be directed. The information above should not be considered legal advice. If you require legal representation, please consult a lawyer.

The Linked Open Data (LOD) community has begun to consider quality issues; there are some

The Linked Open Data (LOD) community has begun to consider quality issues; there are some

Just over one month ago,

Just over one month ago,

Librarians are foot soldiers for the First Amendment–we like open information, we place a high value on the freedom to know. However, we’re among the first to be cut in tight budget situations, and we’re all too familiar with the perils of asking for something that’s overly broad, or asking for something that you can’t show narrowly tailored value for later on.

Librarians are foot soldiers for the First Amendment–we like open information, we place a high value on the freedom to know. However, we’re among the first to be cut in tight budget situations, and we’re all too familiar with the perils of asking for something that’s overly broad, or asking for something that you can’t show narrowly tailored value for later on. Meg Lulofs is an information professional at large, blogging at

Meg Lulofs is an information professional at large, blogging at