THE JUDICIAL CONTEXT: WHY INNOVATE?

The progressive deployment of information and communication technologies (ICT) in the courtroom (audio and video recording, document scanning, courtroom management systems), jointly with the requirement for paperless judicial folders pushed by e-justice plans (Council of the European Union, 2009), are quickly transforming the traditional judicial folder into an integrated multimedia folder, where documents, audio recordings and video recordings can be accessed, usually via a Web-based platform. This trend is leading to a continuous increase in the number and the volume of case-related digital judicial libraries, where the full content of each single hearing is available for online consultation. A typical trial folder contains: audio hearing recordings, audio/video hearing recordings, transcriptions of hearing recordings, hearing reports, and attached documents (scanned text documents, photos, evidences, etc.). The ICT container is typically a dedicated judicial content management system (court management system), usually physically separated and independent from the case management system used in the investigative phase, but interacting with it.

Most of the present ICT deployment has been focused on the deployment of case management systems and ICT equipment in the courtrooms, with content management systems at different organisational levels (court or district). ICT deployment in the judiciary has reached different levels in the various EU countries, but the trend toward full e-justice is clearly in progress. Accessibility of the judicial information, both of case registries (more widely deployed), and of case e-folders, has been strongly enhanced by state-of-the-art ICT technologies. Usability of the electronic judicial folders is still affected by a traditional support toolset, such that an information search is limited to text search, transcription of audio recordings (indispensable for text search) is still a slow and fully manual process, template filling is a manual activity, etc. Part of the information available in the trial folder is not yet directly usable, but requires a time-consuming manual search. Information embedded in audio and video recordings, describing not only what was said in the courtroom, but also the specific trial context and the way in which it was said, still needs to be exploited. While the information is there, information extraction and semantically empowered judicial information retrieval still wait for proper exploitation tools. The growing amount of digital judicial information calls for the development of novel knowledge management techniques and their integration into case and court management systems. In this challenging context a novel case and court management system has been recently proposed.

the deployment of case management systems and ICT equipment in the courtrooms, with content management systems at different organisational levels (court or district). ICT deployment in the judiciary has reached different levels in the various EU countries, but the trend toward full e-justice is clearly in progress. Accessibility of the judicial information, both of case registries (more widely deployed), and of case e-folders, has been strongly enhanced by state-of-the-art ICT technologies. Usability of the electronic judicial folders is still affected by a traditional support toolset, such that an information search is limited to text search, transcription of audio recordings (indispensable for text search) is still a slow and fully manual process, template filling is a manual activity, etc. Part of the information available in the trial folder is not yet directly usable, but requires a time-consuming manual search. Information embedded in audio and video recordings, describing not only what was said in the courtroom, but also the specific trial context and the way in which it was said, still needs to be exploited. While the information is there, information extraction and semantically empowered judicial information retrieval still wait for proper exploitation tools. The growing amount of digital judicial information calls for the development of novel knowledge management techniques and their integration into case and court management systems. In this challenging context a novel case and court management system has been recently proposed.

The JUMAS project (JUdicial MAnagement by digital libraries Semantics) was started in February 2008, with the support of the Polish and Italian Ministries of Justice. JUMAS seeks to realize better usability of multimedia judicial folders — including transcriptions, information extraction, and semantic search –to provide to users a powerful toolset able to fully address the knowledge embedded in the multimedia judicial folder.

The JUMAS project has several objectives:

- (1) direct searching of audio and video sources without a verbatim transcription of the proceedings;

- (2) exploitation of the hidden semantics in audiovisual digital libraries in order to facilitate search and retrieval, intelligent processing, and effective presentation of multimedia information;

- (3) fusing information from multimodal sources in order to improve accuracy during the automatic transcription and the annotation phases;

- (4) optimizing the document workflow to allow the analysis of (un)structured information for document search and evidence-based assessment; and

- (5) supporting a large scale, scalable, and interoperable audio/video retrieval system.

JUMAS is currently under validation in the Court of Wroclaw (Poland) and in the Court of Naples (Italy).

THE DIMENSIONS OF THE PROBLEM

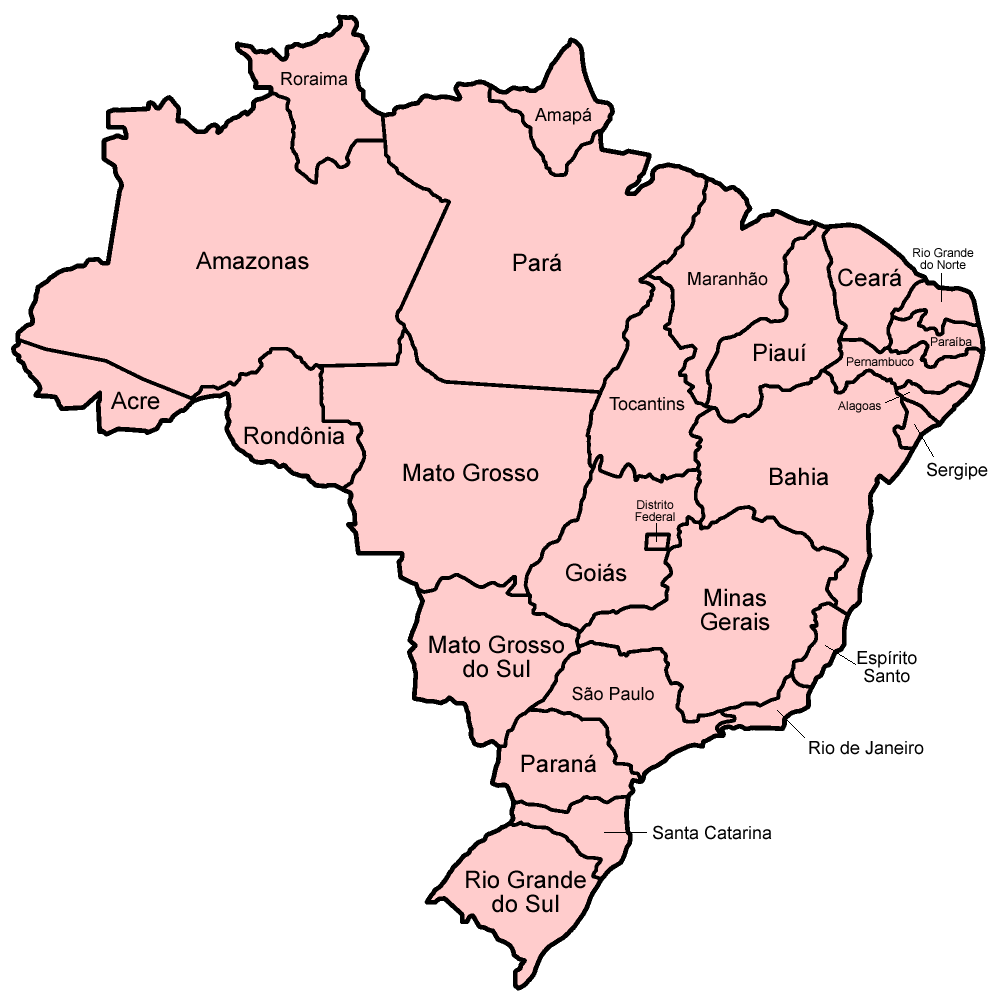

In order to explain the relevance of the JUMAS objectives, we report some volume data related to the judicial domain context. Consider, for instance, the Italian context, where there are 167 courts, grouped in 29 districts, with about 1400 courtrooms. In a law court of medium size (10 courtrooms), during a single legal year, about 150 hearings per court are held, with an average duration of 4 hours. Considering that in approximately 40% of them only audio is recorded, in 20% both audio and video, while the remaining 40% has no recording, the multimedia recording volume we are talking about is 2400 hours of audio and 1200 hours of audio/video per year. The dimensioning related to the audio and audio/video documentation starts from the hypothesis that multimedia sources must be acquired at high quality in order to obtain good results in audio transcription and video annotation, which will affect the performance connected to the retrieval functionalities. Following these requirements, one can figure out a storage space of about 8.7 megabytes per minute (MB/min) for audio and 39 MB/min for audio/video. This means that during a legal year for a court of medium size we need to allocate 4 terabytes (TB) for audio/video material. Under these hypotheses, the overall size generated by all the courts in the justice system — for Italy only — in one year is about 800 TB. This shows how the justice sector is a major contributor to the data deluge (The Economist, 2010).

In order to explain the relevance of the JUMAS objectives, we report some volume data related to the judicial domain context. Consider, for instance, the Italian context, where there are 167 courts, grouped in 29 districts, with about 1400 courtrooms. In a law court of medium size (10 courtrooms), during a single legal year, about 150 hearings per court are held, with an average duration of 4 hours. Considering that in approximately 40% of them only audio is recorded, in 20% both audio and video, while the remaining 40% has no recording, the multimedia recording volume we are talking about is 2400 hours of audio and 1200 hours of audio/video per year. The dimensioning related to the audio and audio/video documentation starts from the hypothesis that multimedia sources must be acquired at high quality in order to obtain good results in audio transcription and video annotation, which will affect the performance connected to the retrieval functionalities. Following these requirements, one can figure out a storage space of about 8.7 megabytes per minute (MB/min) for audio and 39 MB/min for audio/video. This means that during a legal year for a court of medium size we need to allocate 4 terabytes (TB) for audio/video material. Under these hypotheses, the overall size generated by all the courts in the justice system — for Italy only — in one year is about 800 TB. This shows how the justice sector is a major contributor to the data deluge (The Economist, 2010).

In order to manage such quantities of complex data, JUMAS aims to:

- Optimize the workflow of information through search, consultation, and archiving procedures;

- Introduce a higher degree of knowledge through the aggregation of different heterogeneous sources;

- Speed up and improve decision processes by enabling discovery and exploitation of knowledge embedded in multimedia documents, in order to consequently reduce unnecessary costs;

- Model audio-video proceedings in order to compare different instances; and

- Allow traceability of proceedings during their evolution.

THE JUMAS SYSTEM

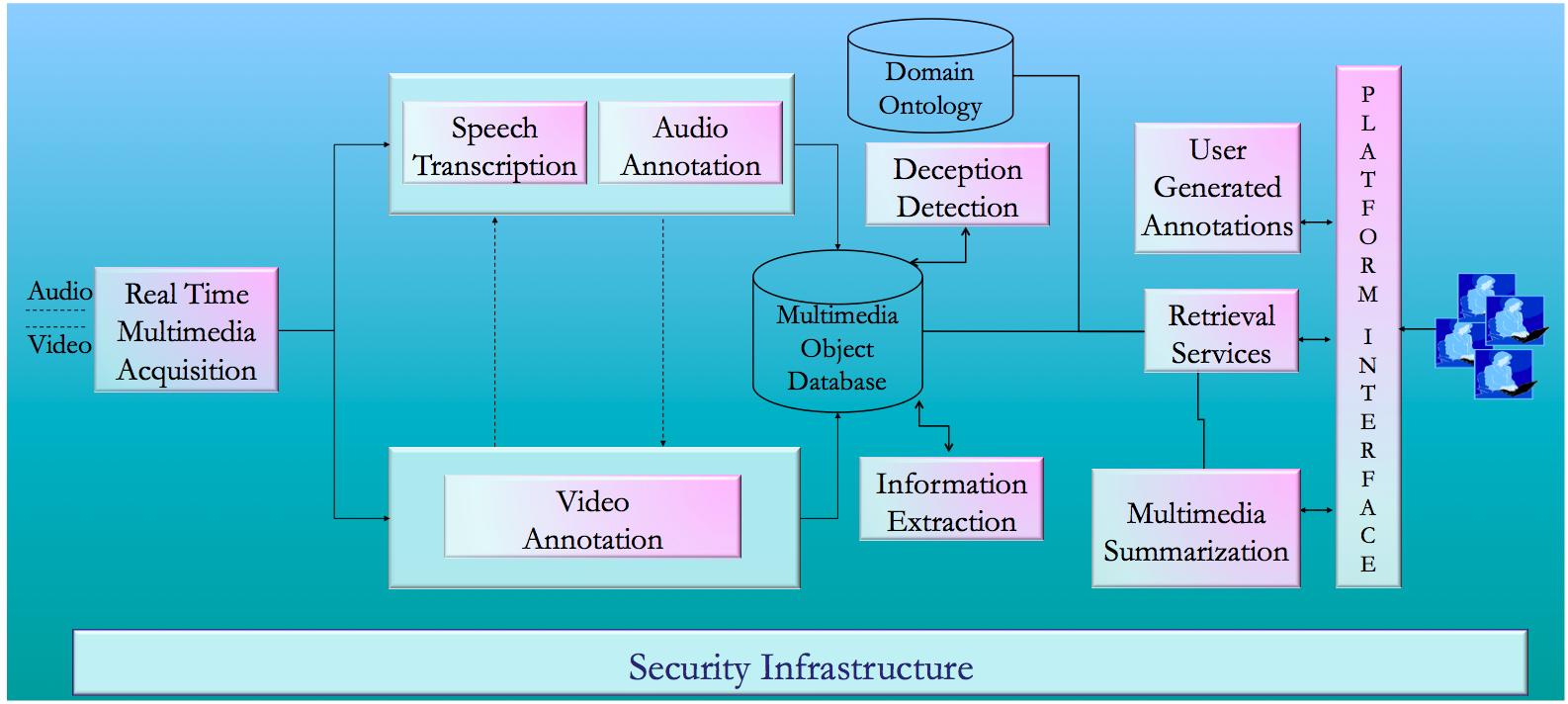

To achieve the above-mentioned goals, the JUMAS project has delivered the JUMAS system, whose main functionalities (depicted in Figure 1) are: automatic speech transcription, emotion recognition, human behaviour annotation, scene analysis, multimedia summarization, template-filling, and deception recognition.

Figure 1: Overview of the JUMAS functionalities

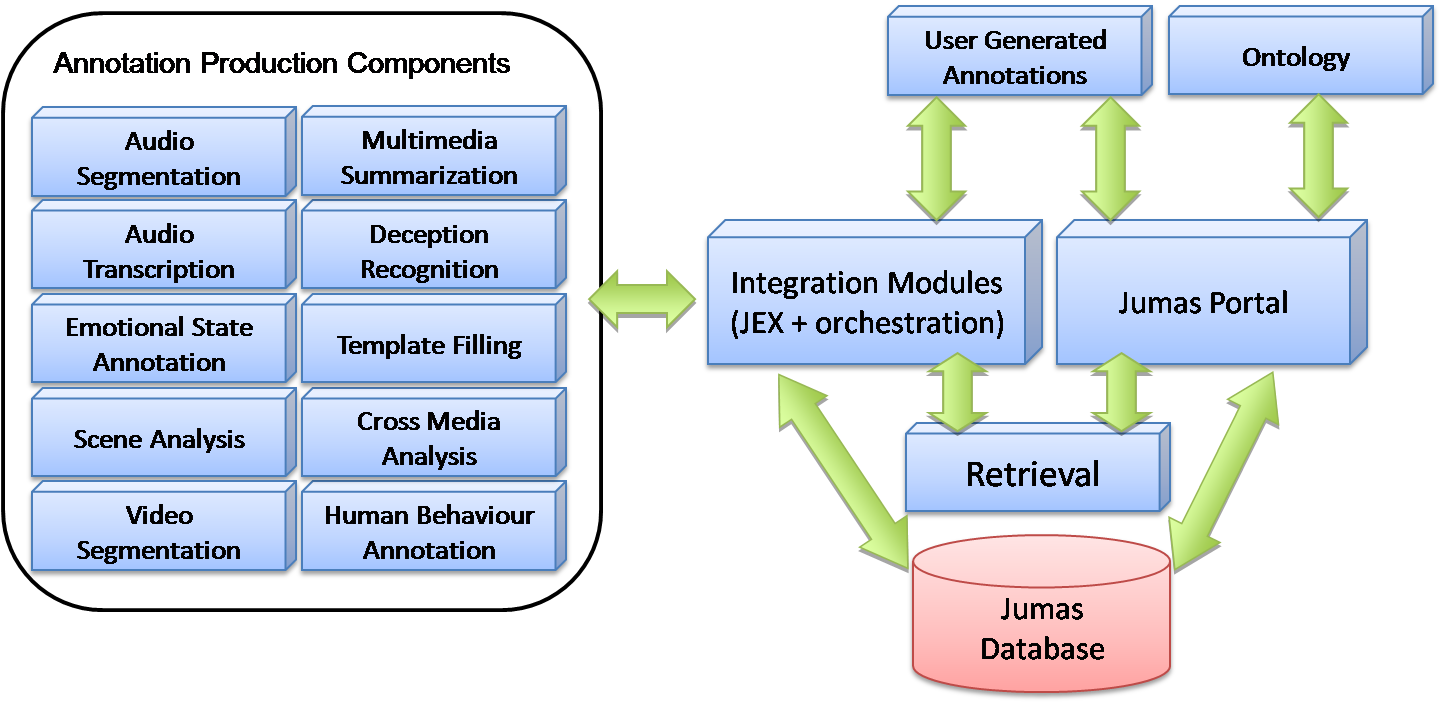

The architecture of JUMAS, depicted in Figure 2, is based on a set of key components: a central database, a user interface on a Web portal, a set of media analysis modules, and an orchestration module that allows the coordination of all system functionalities.

Figure 2: Overview of the JUMAS architecture

The media stream recorded in the courtroom includes both audio and video that are analyzed to extract semantic information used to populate the multimedia object database. The outputs of these processes are annotations: i.e., tags attached to media streams and stored in the database (Oracle 11g). The integration among modules is performed through a workflow engine and a module called JEX (JUMAS EXchange library). While the workflow engine is a service application that manages all the modules for audio and video analysis, JEX provides a set of services to upload and retrieve annotations to and from the JUMAS database.

JUMAS: THE ICT COMPONENTS

KNOWLEDGE EXTRACTION

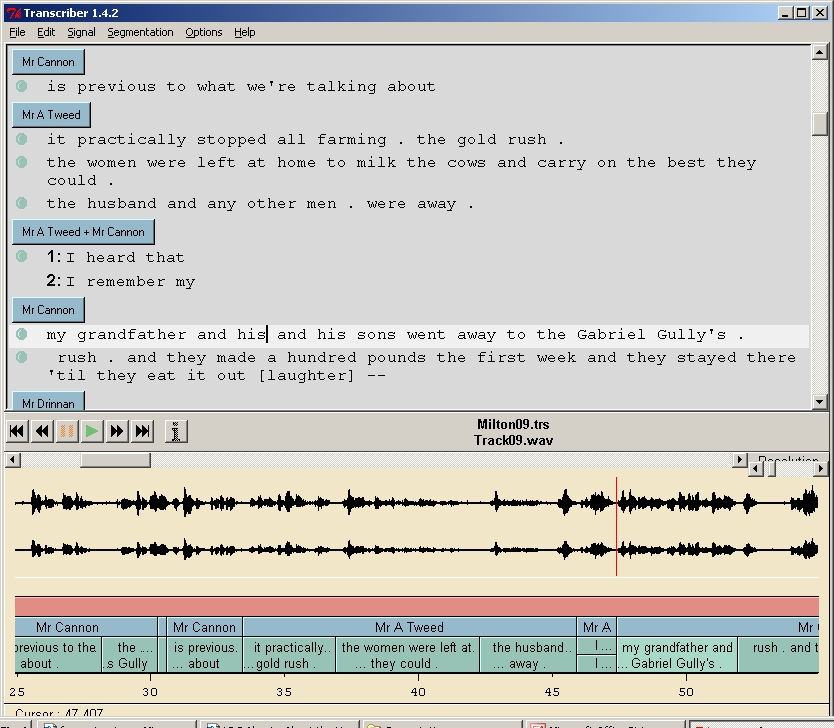

Automatic Speech Transcription. For courtroom users, the primary sources of information are audio-recordings of hearings/proceedings. In light of this, JUMAS provides an Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) system (Falavigna et al., 2009 and Rybach et al., 2009) trained on real judicial data coming from courtrooms. Currently two ASR systems have been developed: the first provided by Fondazione Bruno Kessler for the Italian language, and the second delivered by RWTH Aachen University for the Polish language. Currently, the ASR modules in the JUMAS system offer 61% accuracy over the generated automatic transcriptions, and represent the first contribution for populating the digital libraries with judicial trial information. In fact, the resulting transcriptions are the main information resource that are to be enriched by other modules, and then can be consulted by end users through the information retrieval system.

Automatic Speech Transcription. For courtroom users, the primary sources of information are audio-recordings of hearings/proceedings. In light of this, JUMAS provides an Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) system (Falavigna et al., 2009 and Rybach et al., 2009) trained on real judicial data coming from courtrooms. Currently two ASR systems have been developed: the first provided by Fondazione Bruno Kessler for the Italian language, and the second delivered by RWTH Aachen University for the Polish language. Currently, the ASR modules in the JUMAS system offer 61% accuracy over the generated automatic transcriptions, and represent the first contribution for populating the digital libraries with judicial trial information. In fact, the resulting transcriptions are the main information resource that are to be enriched by other modules, and then can be consulted by end users through the information retrieval system.

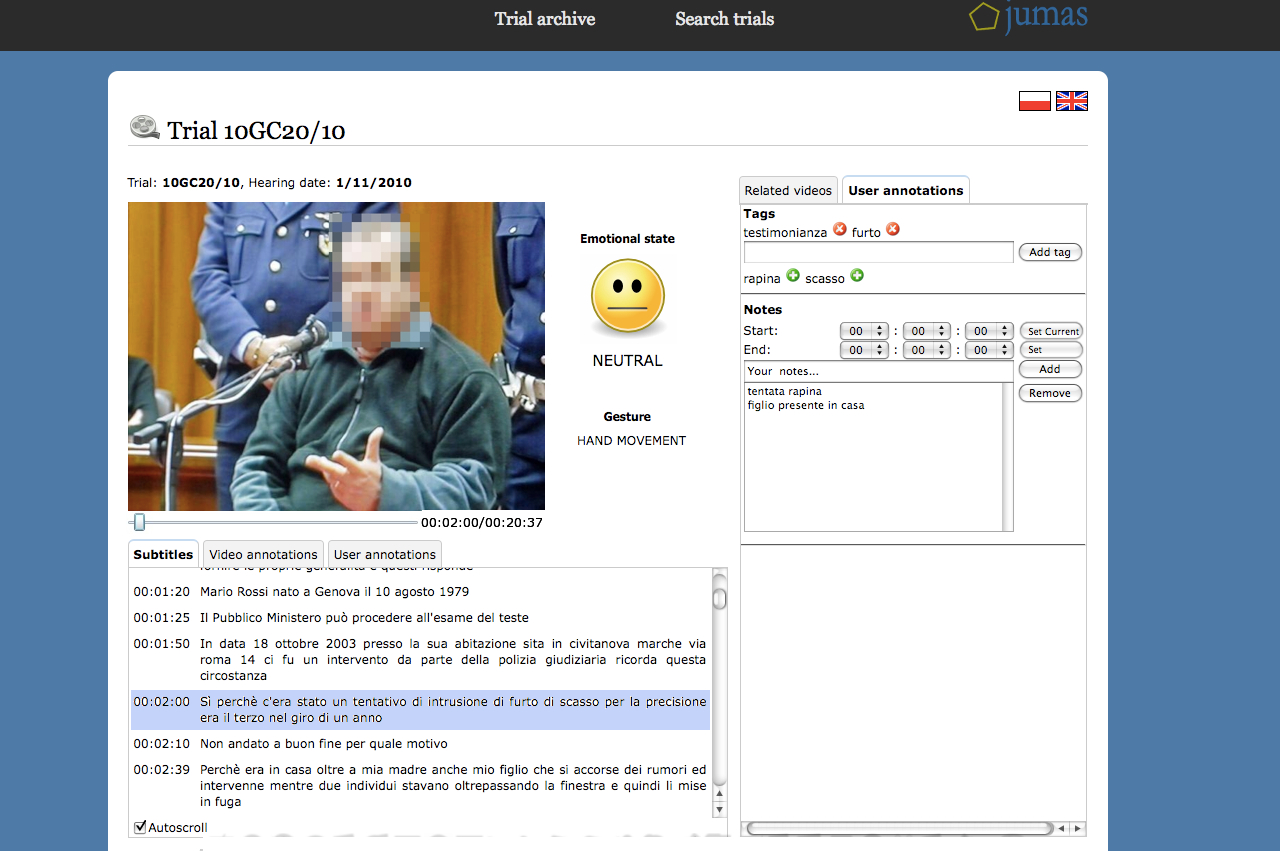

Emotion Recognition. Emotional states represent an aspect of knowledge embedded into courtroom media streams that may be used to enrich the content available in multimedia digital libraries. Enabling the end user to consult transcriptions by considering the associated semantics as well, represents an important achievement, one that allows the end user to retrieve an enriched written sentence instead of a “flat” one. Even if there is an open ethical discussion about the usability of this kind of information, this achievement radically changes the consultation process: sentences can assume different meanings according to the affective state of the speaker. To this purpose an emotion recognition module (Archetti et al., 2008), developed by the Consorzio Milano Ricerche jointly with the University of Milano-Bicocca, is part of the JUMAS system. A set of real-world human emotions obtained from courtroom audio recordings has been gathered for training the underlying supervised learning model.

Emotion Recognition. Emotional states represent an aspect of knowledge embedded into courtroom media streams that may be used to enrich the content available in multimedia digital libraries. Enabling the end user to consult transcriptions by considering the associated semantics as well, represents an important achievement, one that allows the end user to retrieve an enriched written sentence instead of a “flat” one. Even if there is an open ethical discussion about the usability of this kind of information, this achievement radically changes the consultation process: sentences can assume different meanings according to the affective state of the speaker. To this purpose an emotion recognition module (Archetti et al., 2008), developed by the Consorzio Milano Ricerche jointly with the University of Milano-Bicocca, is part of the JUMAS system. A set of real-world human emotions obtained from courtroom audio recordings has been gathered for training the underlying supervised learning model.

Human Behavior Annotation. A further fundamental information resource is related to the video stream. In addition to emotional states identification, the recognition of relevant events that characterize judicial proceedings can be valuable for end users. Relevant events occurring during proceedings trigger meaningful gestures, which emphasize and anchor the words of witnesses, and highlight that a relevant concept has been explained. For this reason, the human behavior recognition modules (Briassouli et al., 2009, Kovacs et al., 2009), developed by CERTH-ITI and by MTA SZTAKI Research Institute, have been included in the JUMAS system. The video analysis captures relevant events that occur during the course of a trial in order to create semantic annotations that can be retrieved by judicial end users. The annotations are mainly concerned with the events related to the witness: change of posture, change of witness, hand gestures, gestures indicating conflict or disagreement.

Human Behavior Annotation. A further fundamental information resource is related to the video stream. In addition to emotional states identification, the recognition of relevant events that characterize judicial proceedings can be valuable for end users. Relevant events occurring during proceedings trigger meaningful gestures, which emphasize and anchor the words of witnesses, and highlight that a relevant concept has been explained. For this reason, the human behavior recognition modules (Briassouli et al., 2009, Kovacs et al., 2009), developed by CERTH-ITI and by MTA SZTAKI Research Institute, have been included in the JUMAS system. The video analysis captures relevant events that occur during the course of a trial in order to create semantic annotations that can be retrieved by judicial end users. The annotations are mainly concerned with the events related to the witness: change of posture, change of witness, hand gestures, gestures indicating conflict or disagreement.

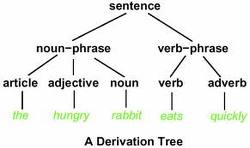

Deception Detection. Discriminating between truthful and deceptive assertions is one of the most important activities performed by judges, lawyers, and prosecutors. In order to support these individuals’ reasoning activities, respecting corroborating/contradicting declarations (in the case of lawyers and prosecutors) and judging the accused (judges), a deception recognition module has been developed as a support tool. The deception detection module developed by the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies is based on the automatic classification of sentences performed by the ASR systems (Ganter and Strube, 2009). In particular, in order to train the deception detection module, a manual annotation of the output of the ASR module — with the help of the minutes of the transcribed sessions — has been performed. The knowledge extracted for training the classification module deals with lies, contradictory statements, quotations, and expressions of vagueness.

Deception Detection. Discriminating between truthful and deceptive assertions is one of the most important activities performed by judges, lawyers, and prosecutors. In order to support these individuals’ reasoning activities, respecting corroborating/contradicting declarations (in the case of lawyers and prosecutors) and judging the accused (judges), a deception recognition module has been developed as a support tool. The deception detection module developed by the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies is based on the automatic classification of sentences performed by the ASR systems (Ganter and Strube, 2009). In particular, in order to train the deception detection module, a manual annotation of the output of the ASR module — with the help of the minutes of the transcribed sessions — has been performed. The knowledge extracted for training the classification module deals with lies, contradictory statements, quotations, and expressions of vagueness.

Information Extraction. The current amount of unstructured textual data available in the judicial domain, especially related to transcriptions of proceedings, highlights the necessity of automatically extracting structured data from unstructured material, to facilitate efficient consultation processes. In order to address the problem of structuring data coming from the automatic speech transcription system, Consorzio Milano Ricerche has defined an environment that combines regular expressions, probabilistic models, and background information available in each court database system. Thanks to this functionality, the judicial actors can view each individual hearing as a structured summary, where the main information extracted consists of the names of the judge, lawyers, defendant, victim, and witnesses; the names of the subjects cited during a deposition; the date cited during a deposition; and data about the verdict.

Information Extraction. The current amount of unstructured textual data available in the judicial domain, especially related to transcriptions of proceedings, highlights the necessity of automatically extracting structured data from unstructured material, to facilitate efficient consultation processes. In order to address the problem of structuring data coming from the automatic speech transcription system, Consorzio Milano Ricerche has defined an environment that combines regular expressions, probabilistic models, and background information available in each court database system. Thanks to this functionality, the judicial actors can view each individual hearing as a structured summary, where the main information extracted consists of the names of the judge, lawyers, defendant, victim, and witnesses; the names of the subjects cited during a deposition; the date cited during a deposition; and data about the verdict.

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

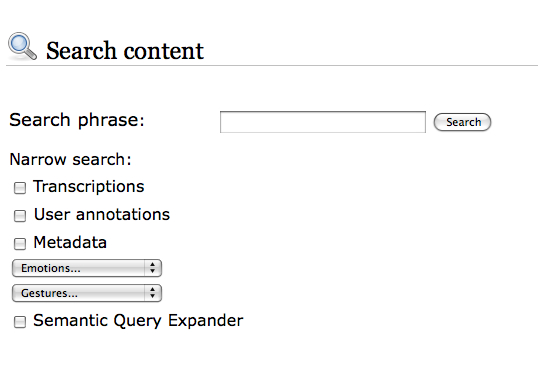

Information Retrieval. Currently, to retrieve audio/video materials acquired during a trial, the end user must manually consult all of the multimedia tracks. The identification of a particular position or segment of a multimedia stream, for purposes of looking at and/or listening to specific declarations, is possible either by remembering the time stamp when the events occurred, or by watching or hearing the whole recording. The amalgamation of automatic transcriptions, semantic annotations, and ontology representations allows us to build a flexible retrieval environment, based not only on simple textual queries, but also on broad and complex concepts. In order to define an integrated platform for cross-modal access to audio and video recordings and their automatic transcriptions, a retrieval module able to perform semantic multimedia indexing and retrieval has been developed by the Information Retrieval group at MTA SZTAKI. (Darczy et al., 2009)

Information Retrieval. Currently, to retrieve audio/video materials acquired during a trial, the end user must manually consult all of the multimedia tracks. The identification of a particular position or segment of a multimedia stream, for purposes of looking at and/or listening to specific declarations, is possible either by remembering the time stamp when the events occurred, or by watching or hearing the whole recording. The amalgamation of automatic transcriptions, semantic annotations, and ontology representations allows us to build a flexible retrieval environment, based not only on simple textual queries, but also on broad and complex concepts. In order to define an integrated platform for cross-modal access to audio and video recordings and their automatic transcriptions, a retrieval module able to perform semantic multimedia indexing and retrieval has been developed by the Information Retrieval group at MTA SZTAKI. (Darczy et al., 2009)

Ontology as Support to Information Retrieval. An ontology is a formal representation of the knowledge that characterizes a given domain, through a set of concepts and a set of relationships that obtain among them. In the judicial domain, an ontology represents a key element that supports the retrieval process performed by end users. Text-based retrieval functionalities are not sufficient for finding and consulting transcriptions (and other documents) related to a given trial. A first contribution of the ontology component developed by the University of Milano-Bicocca (CSAI Research Center) for the JUMAS system provides query expansion functionality. Query expansion aims at extending the original query specified by end users with additional related terms. The whole set of keywords is then automatically submitted to the retrieval engine. The main objective is to narrow the search focus or to increase recall.

User Generated Semantic Annotations. Judicial users usually manually tag some documents for purposes of highlighting (and then remembering) significant portions of the proceedings. An important functionality, developed by the European Media Laboratory and offered by the JUMAS system, relates to the possibility of digitally annotating relevant arguments discussed during a proceeding. In this context, the user-generated annotations may aid judicial users in future retrieval and reasoning processes. The user-generated annotations module included in the JUMAS system allows end users to assign free tags to multimedia content in order to organize the trials according to their personal preferences. It also enables judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and court clerks to work collaboratively on a trial; e.g., a prosecutor who is taking over a trial can build on the notes of his or her predecessor.

KNOWLEDGE VISUALIZATION

Hyper Proceeding Views. The user interface of JUMAS — developed by ESA Projekt and Consorzio Milano Ricerche — is a Web portal, in which the contents of the database are presented in different views. The basic view allows browsing of the trial archive, as in a typical court management system, to view general information (dates of hearings, name of people involved) and documents attached to each trial. JUMAS’s distinguishing features include the automatic creation of a summary of the trial, the presentation of user-generated annotations, and the Hyper Proceeding View: i.e., an advanced presentation of media contents and annotations that allows the user to perform queries on contents, and jump directly to relevant parts of media files.

Hyper Proceeding Views. The user interface of JUMAS — developed by ESA Projekt and Consorzio Milano Ricerche — is a Web portal, in which the contents of the database are presented in different views. The basic view allows browsing of the trial archive, as in a typical court management system, to view general information (dates of hearings, name of people involved) and documents attached to each trial. JUMAS’s distinguishing features include the automatic creation of a summary of the trial, the presentation of user-generated annotations, and the Hyper Proceeding View: i.e., an advanced presentation of media contents and annotations that allows the user to perform queries on contents, and jump directly to relevant parts of media files.

Multimedia Summarization. Digital videos represent a fundamental information resource about the events that occur during a trial: such videos can be stored, organized, and retrieved in a short time and at low cost. However, considering the dimensions that a video resource can assume during the recording of a trial, judicial actors have specified several requirements for digital trial videos: fast navigation of the stream, efficient access to data within the stream, and effective representation of relevant contents. One possible solution to these requirements lies in multimedia summarization, which derives a synthetic representation of audio/video contents with a minimal loss of meaningful information. In order to address the problem of defining a short and meaningful representation of a proceeding, a multimedia summarization environment based on an unsupervised learning approach has been developed (Fersini et al., 2010) by Consorzio Milano Ricerche jointly with University of Milano-Bicocca.

CONCLUSION

The JUMAS project demonstrates the feasibility of enriching a court management system with an advanced toolset for extracting and using the knowledge embedded in a multimedia judicial folder. Automatic transcription, template filling, and semantic enrichment help judicial actors not only to save time, but also to enhance the quality of their judicial decisions and performance. These improvements are mainly due to the ability to search not only text, but also events that occur in the courtroom. The initial results of the JUMAS project indicate that automatic transcription and audio/video annotations can provide additional information in an affordable way.

Elisabetta Fersini has a post-doctoral research fellow position at the University of Milano-Bicocca. She received her PhD with a thesis on “Probabilistic Classification and Clustering using Relational Models.” Her research interest is mainly focused on (Relational) Machine Learning in several domains, including Justice, Web, Multimedia, and Bioinformatics.

VoxPopuLII is edited by Judith Pratt.

Editor-in-Chief is Robert Richards, to whom queries should be directed.

The biggest advantage of established legal publishing houses, as opposed to new start-ups, is their brand recognition, and the chance to position themselves as gatekeepers for high quality information. The corresponding threat is –- again –- based on new technologies: Services such as

The biggest advantage of established legal publishing houses, as opposed to new start-ups, is their brand recognition, and the chance to position themselves as gatekeepers for high quality information. The corresponding threat is –- again –- based on new technologies: Services such as